| Renaissance |

|---|

|

| Aspects |

| Regions |

| History and study |

During the Renaissance, great advances occurred in geography, astronomy, chemistry, physics, mathematics, manufacturing, anatomy and engineering. The collection of ancient scientific texts began in earnest at the start of the 15th century and continued up to the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, and the invention of printing allowed a faster propagation of new ideas. Nevertheless, some have seen the Renaissance, at least in its initial period, as one of scientific backwardness. Historians like George Sarton and Lynn Thorndike criticized how the Renaissance affected science, arguing that progress was slowed for some amount of time. Humanists favored human-centered subjects like politics and history over study of natural philosophy or applied mathematics. More recently, however, scholars have acknowledged the positive influence of the Renaissance on mathematics and science, pointing to factors like the rediscovery of lost or obscure texts and the increased emphasis on the study of language and the correct reading of texts.[1][2][3]

Marie Boas Hall coined the term Scientific Renaissance to designate the early phase of the Scientific Revolution, 1450–1630. More recently, Peter Dear has argued for a two-phase model of early modern science: a Scientific Renaissance of the 15th and 16th centuries, focused on the restoration of the natural knowledge of the ancients; and a Scientific Revolution of the 17th century, when scientists shifted from recovery to innovation.

Context

During and after the Renaissance of the 12th century, Europe experienced an intellectual revitalization, especially with regard to the investigation of the natural world. In the 14th century, however, a series of events that would come to be known as the Crisis of the Late Middle Ages was underway. When the Black Death came, it wiped out so many lives it affected the entire system. It brought a sudden end to the previous period of massive scientific change. The plague killed 25–50% of the people in Europe, especially in the crowded conditions of the towns, where the heart of innovations lay. Recurrences of the plague and other disasters caused a continuing decline of population for a century.

The Renaissance

The 14th century saw the beginning of the cultural movement of the Renaissance. By the early 15th century, an international search for ancient manuscripts was underway and would continue unabated until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, when many Byzantine scholars had to seek refuge in the West, particularly Italy.[4] Likewise, the invention of the printing press was to have great effect on European society: the facilitated dissemination of the printed word democratized learning and allowed a faster propagation of new ideas.

Initially, there were no new developments in physics or astronomy, and the reverence for classical sources further enshrined the Aristotelian and Ptolemaic views of the universe. Renaissance philosophy lost much of its rigor as the rules of logic and deduction were seen as secondary to intuition and emotion. At the same time, Renaissance humanism stressed that nature came to be viewed as an animate spiritual creation that was not governed by laws or mathematics. Only later, when no more manuscripts could be found, did humanists turn from collecting to editing and translating them, and new scientific work began with the work of such figures as Copernicus, Cardano, and Vesalius.

Important developments

Alchemy and chemistry

While differing in some respects, alchemy and chemistry often had similar goals during the Renaissance period, and together they are sometimes referred to as chymistry.[5] Alchemy is the study of the transmutation of materials through obscure processes. Although it is often viewed as a pseudoscientific endeavor, many of its practitioners utilized widely accepted scientific theories of their times to formulate hypotheses about the constituents of matter and the ways matter could be changed.[6] One of the main aims of alchemists was to find a method of creating gold and other precious metals from the transmutation of base materials.[6] A common belief of alchemists was that there is an essential substance from which all other substances formed, and that if you could reduce a substance to this original material, you could then construct it into another substance, like lead to gold.[5] Medieval alchemists worked with two main elements or "principles", sulphur and mercury.[5]

Paracelsus was a chymist and physician of the Renaissance period who believed that, in addition to sulphur and mercury, salt served as one of the primary alchemical principles from which everything else was made.[7] Paracelsus was also instrumental in helping to put chemical practices to practical medicinal use through a recognition that the body operates through processes which may be seen as chemical in nature.[7] These lines of thinking directly conflicted with many long-held traditional beliefs, such as those popularized by Aristotle; however, Paracelsus was insistent that questioning principles of nature was essential to continue the general growth of knowledge.[7]

Despite its frequent basis in what may be considered scientific practices by modern standards, numerous factors caused chymistry as a discipline to remain separate from general academia until near the end of the Renaissance, when it finally began appearing as a portion of some university education.[5][8]: 104–115 The commercial nature of chymistry at the time, along with the lack of classical basis for the practice, were some of the contributing factors which led to the general view of the discipline as a craft rather than a respectable academic discipline.[5]

Astronomy

_Ex_Libris_rare_-_Mario_Taddei.JPG.webp)

The astronomy of the late Middle Ages was based on the geocentric model described by Claudius Ptolemy in antiquity. Probably very few practicing astronomers or astrologers actually read Ptolemy's Almagest, which had been translated into Latin by Gerard of Cremona in the 12th century. Instead they relied on introductions to the Ptolemaic system such as the De sphaera mundi of Johannes de Sacrobosco and the genre of textbooks known as Theorica planetarum. For the task of predicting planetary motions they turned to the Alfonsine tables, a set of astronomical tables based on the Almagest models but incorporating some later modifications, mainly the trepidation model attributed to Thabit ibn Qurra. Contrary to popular belief, astronomers of the Middle Ages and Renaissance did not resort to "epicycles on epicycles" in order to correct the original Ptolemaic models—until one comes to Copernicus himself.

Sometime around 1450, mathematician Georg Purbach (1423–1461) began a series of lectures on astronomy at the University of Vienna. Regiomontanus (1436–1476), who was then one of his students, collected his notes on the lecture and later published them as Theoricae novae planetarum in the 1470s. This "New Theorica" replaced the older theorica as the textbook of advanced astronomy. Purbach also began to prepare a summary and commentary on the Almagest. He died after completing only six books, however, and Regiomontanus continued the task, consulting a Greek manuscript brought from Constantinople by Cardinal Bessarion. When it was published in 1496, the Epitome of the Almagest made the highest levels of Ptolemaic astronomy widely accessible to many European astronomers for the first time.

The last major event in Renaissance astronomy is the work of Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543). He was among the first generation of astronomers to be trained with the Theoricae novae and the Epitome. Shortly before 1514 he began to revive Aristarchus's idea that the Earth revolves around the Sun. He spent the rest of his life attempting a mathematical proof of heliocentrism. When De revolutionibus orbium coelestium was finally published in 1543, Copernicus was on his deathbed. A comparison of his work with the Almagest shows that Copernicus was in many ways a Renaissance scientist rather than a revolutionary, because he followed Ptolemy's methods and even his order of presentation. Not until the works of Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) and Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) was Ptolemy's manner of doing astronomy superseded. The use of more advanced tables and mathematics would provide the impetus for the establishment of the Gregorian calendar in 1582 (primarily to reform the calculation of the date of Easter), replacing the Julian calendar, which had several errors.[8]: 69–72

Mathematics

The accomplishments of Greek mathematicians survived throughout Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages through a long and indirect history. Much of the work of Euclid, Archimedes, and Apollonius, along with later authors such as Hero and Pappus, were copied and studied in both Byzantine culture and in Islamic centers of learning. Translations of these works began already in the 12th century, with the work of translators in Spain and Sicily, working mostly from Arabic and Greek sources into Latin. Two of the most prolific were Gerard of Cremona and William of Moerbeke.

The greatest of all translation efforts, however, took place in the 15th and 16th centuries in Italy, as attested by the numerous manuscripts dating from this period currently found in European libraries. Virtually all leading mathematicians of the era were obsessed with the need for restoring the mathematical works of the ancients. Not only did humanists assist mathematicians with the retrieval of Greek manuscripts, they also took an active role in translating these work into Latin, often commissioned by religious leaders such as Nicholas V and Cardinal Bessarion.[10][11]

Some of the leading figures in this effort include Regiomontanus, who made a copy of the Latin Archimedes and had a program for printing mathematical works; Commandino (1509–1575), who likewise produced an edition of Archimedes, as well as editions of works by Euclid, Hero, and Pappus; and Maurolyco (1494–1575), who not only translated the work of ancient mathematicians but added much of his own work to these. Their translations ensured that the next generation of mathematicians would be in possession of techniques far in advance of what it was generally available during the Middle Ages.[1][3]

It must be borne in mind that the mathematical output of the 15th and 16th centuries was not exclusively limited to the works of the ancient Greeks. Some mathematicians, such as Tartaglia and Luca Paccioli, welcomed and expanded on the medieval traditions of both Islamic scholars and people like Jordanus and Fibonnacci.[12][13] Giordano Bruno was also one to critique the works of people like Aristotle, whom he believed to have a flawed logic and developed a mathematical doctrine for the computation of partial physics, with Bruno attempting to transform theories of nature.[14]

Physics

The progress being made in math was complemented by advancements in physics, with people like Galileo attempting to bridge the gap between the two fields and question Aristotelian ideas.[15] The revived invertigation of physics opened up many opportunities in subfields like mechanics, optics, navigation, and cartography.[8]: 79–89

Mechanical theories had originated with the Greeks, especially Aristotle and Archimedes.[8]: 79–82 Mechanics and philosophy had been related disciplines in ancient Greece, and only in the Renaissance did the two subjects begin to split.[8]: 79–82 A lot of the work of developing new mechanical ideas and theories was carried out by Italians such as Rafael Bombelli, though the Fleming Simon Stevin also provided many ideas.[8]: 79–82 Galileo also contributed to the advancement of this field with a treatise on mechanics in 1593,[15] helping to develop ideas on relativity, freely falling bodies, and accelerated linear motion,[16] though he lacked the means to properly communicate his findings at the time.[15] In June 1609, Galileo's interests shifted to his telescopic investigations after having been close to revolutionizing the science of mechanics.[15]

Navigation was an important topic of the time, and many innovations were made that, with the introduction of better ships and applications of the compass, would later lead to geographical discoveries.[8]: 89–91 The calculations involved in navigation proved to be difficult, with the technology of the time unable to accuately predict weather or determine one's geographic position. Determining one's longitude proved especially challenging, since one's local time need to be calculated on the basis of an astonomical observation.[8]: 89–91 One theory that was tested was to record the time of an eclipse and use Regiomontanus' Ephemerides to compare it with Nuremberg time or Zacuto's Almanach perpetuum to compare it with Salamanca time, though the margin of error in such calculations was unacceptably great (around 25.5 degrees).[8]: 89–91 Until longitude could be accurately determined, navigators had to rely on dead reckoning, with its many uncertainties.[8]: 89–91

Medicine

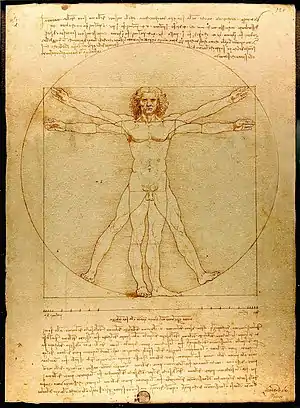

With the Renaissance came an increase in experimental investigation, principally in the field of dissection and body examination, thus advancing our knowledge of human anatomy.[17] The development of modern neurology began in the 16th century with Andreas Vesalius, who described the anatomy of the brain and other organs; he had little knowledge of the brain's function, thinking that it resided mainly in the ventricles. Understanding of medical sciences and diagnosis improved, but with little direct benefit to health care. Few effective drugs existed, beyond opium and quinine. William Harvey provided a refined and complete description of the circulatory system. The most useful tomes in medicine, used both by students and expert physicians, were materiae medicae and pharmacopoeiae.

Geography and the New World

In the history of geography, the key classical text was the Geographia of Claudius Ptolemy (2nd century). It was translated into Latin in the 15th century by Jacopo d'Angelo.[18] It was widely read in manuscript and went through many print editions after it was first printed in 1475. Regiomontanus worked on preparing an edition for print prior to his death; his manuscripts were consulted by later mathematicians in Nuremberg. Ptolemy's Geographia became the basis for most maps made in Europe throughout the 15th century.[18] Even as new knowledge began to replace the content of old maps, the rediscovery of Ptolemy's mapping system, including the use of coordinates and projection, helped to redefine the overall field of cartography as a scientific pursuit rather than an artistic one.[18]

The information provided by Ptolemy, as well as Pliny the Elder and other classical sources, was soon seen to be in contradiction to the lands explored in the Age of Discovery.[18] The new discoveries revealed shortcomings in classical knowledge; they also opened European imagination to new possibilities. In particular, Christopher Columbus' voyage to the New World in 1492 helped set the tone for what would soon after become a wave of European expansion.[19] Thomas More's Utopia was inspired partly by the discovery of the New World. Most maps developed prior to this period grossly underestimated the extent of the lands separating Europe from India on a westward route through the New World; however, through contributions of explorers such as Ferdinand Magellan, efforts were made to create more accurate maps during this period.[20]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Rose, Paul Lawrence (1973). "Humanist Culture and Renaissance Mathematics: The Italian Libraries of the Quattrocento". Studies in the Renaissance. 20: 46–105. doi:10.2307/2857013. ISSN 0081-8658. JSTOR 2857013.

- ↑ Anglin, W. S.; Lambek, J. (1995), Anglin, W. S.; Lambek, J. (eds.), "Mathematics in the Renaissance", The Heritage of Thales, Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics, New York, NY: Springer, pp. 125–131, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0803-7_25, ISBN 978-1-4612-0803-7, retrieved 2021-04-09

- 1 2 Jayawardene, S. A. (June 1978). "The Italian Renaissance of Mathematics: Studies on Humanists and Mathematicians from Petrarch to Galileo. Paul Lawrence Rose". Isis. 69 (2): 298–300. doi:10.1086/352043. ISSN 0021-1753.

- ↑ Hall, Marie Boas (1994-01-01). The Scientific Renaissance 1450-1630. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-28115-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Principe, Lawrence (2011). The Scientific Revolution: A Very Short Introduction. Very Short Introductions (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956741-6.

- 1 2 Lindberg, David C. (2007). The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Scientific Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, Prehistory to A.D. 1450 (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 290–294. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- 1 2 3 Moran, Bruce T. (2019). Paracelsus: An Alchemical Life. Renaissance lives. London, UK: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78914-144-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Sarton, George (1967). Six Wings: Men of Science in the Renaissance. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- ↑ Høyrup, Jens (2019), "Archimedes: Reception in the Renaissance", in Sgarbi, Marco (ed.), Encyclopedia of Renaissance Philosophy, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–7, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-02848-4_892-1, ISBN 978-3-319-02848-4, S2CID 212949014, retrieved 2021-04-23

- ↑ "Mathematics - Rome Reborn: The Vatican Library & Renaissance Culture | Exhibitions - Library of Congress". www.loc.gov. 1993-01-08. Retrieved 2021-04-09.

- ↑ Gouwens, Kenneth (1996-09-22). "Rome Reborn: The Vatican Library and Renaissance Culture". Renaissance Quarterly. 49 (3): 618–620. doi:10.2307/2863370. JSTOR 2863370. S2CID 191382178.

- ↑ Malet, Antoni (2006-02-01). "Renaissance notions of number and magnitude". Historia Mathematica. 33 (1): 63–81. doi:10.1016/j.hm.2004.11.011. ISSN 0315-0860.

- ↑ Høyrup, Jens (2003). Practitioners – school teachers – "mathematicians": The divisions of pre-Modern mathematics and its actors. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.529.862.

- ↑ Gatti, Hilary (1999). Giordano Bruno and Renaissance Science. Cornell University. p. 144. ISBN 0-8014-3529-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Singleton, Charles Southward, ed. (1970). Art, Science, and History in the Renaissance. The Johns Hopkins Humanities Seminars (2. printing ed.). Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins Press. pp. 310–318. ISBN 978-0-8018-0602-5.

- ↑ Asim, Gangopadhyaya (2017). "Galileo's Contribution to Mechanics". Loyola eCommons: 90–94.

- ↑ Siraisi, N. G. (2012). "Medicine, 1450–1620, and the History of Science". Isis. 103 (3): 491–514. doi:10.1086/667970. PMID 23286188. S2CID 6954963.

- 1 2 3 4 Hunt, Arthur (2000). "2000 Years of Map Making". Geography. 85 (1): 3–14. ISSN 0016-7487. JSTOR 40573370.

- ↑ Cortada, James W. (1974). "Who Was Christopher Columbus?". Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Réforme. 10 (2): 99–102. doi:10.33137/rr.v10i2.13735. ISSN 0034-429X. JSTOR 43464886.

- ↑ Heawood, Edward (1921). "The World Map Before and After Magellan's Voyage". The Geographical Journal. 57 (6): 431–442. Bibcode:1921GeogJ..57..431H. doi:10.2307/1780791. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 1780791.

References

- Dear, Peter. Revolutionizing the Sciences: European Knowledge and Its Ambitions, 1500–1700. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- Debus, Allen G. Man and Nature in the Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

- Grafton, Anthony, et al. New Worlds, Ancient Texts: The Power of Tradition and the Shock of Discovery. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1992.

- Hall, Marie Boas. The Scientific Renaissance, 1450–1630. New York: Dover Publications, 1962, 1994.

External links

- Renaissance science and technology at Britannica.com