| Swabian | |

|---|---|

| Schwäbisch,[1] schwäbische Mundart[2] | |

| Native to | Germany[1] |

| Ethnicity | Swabians |

Native speakers | 820,000 (2006)[3] |

| Latin (German alphabet) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | swg |

| Glottolog | swab1242 |

| IETF | swg[4] |

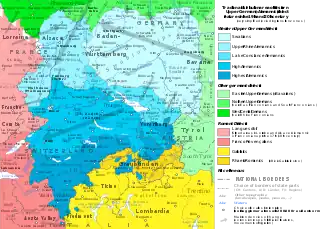

Areas where Alemannic dialects are spoken Swabian | |

Swabian (German: Schwäbisch [ˈʃvɛːbɪʃ] ⓘ) is one of the dialect groups of Upper German, sometimes one of the dialect groups of Alemannic German (in the broad sense),[5] that belong to the High German dialect continuum. It is mainly spoken in Swabia, which is located in central and southeastern Baden-Württemberg (including its capital Stuttgart and the Swabian Jura region) and the southwest of Bavaria (Bavarian Swabia). Furthermore, Swabian German dialects are spoken by Caucasus Germans in Transcaucasia.[6] The dialects of the Danube Swabian population of Hungary, the former Yugoslavia and Romania are only nominally Swabian and can be traced back not only to Swabian but also to Franconian, Bavarian and Hessian dialects, with locally varying degrees of influence of the initial dialects.[7]

Description

Swabian can be difficult to understand for speakers of Standard German due to its pronunciation and partly differing grammar and vocabulary.

In 2009, the word Muggeseggele (a Swabian idiom), meaning the scrotum of a housefly, was voted in a readers' survey by Stuttgarter Nachrichten, the largest newspaper in Stuttgart, as the most beautiful Swabian word, well ahead of any other term.[8] The expression is used in an ironic way to describe a small unit of measure and is deemed appropriate to use in front of small children (compare Bubenspitzle). German broadcaster SWR's children's website, Kindernetz, explained the meaning of Muggeseggele in their Swabian dictionary in the Swabian-based TV series Ein Fall für B.A.R.Z.[9]

Characteristics

- The ending "-ad" is used for verbs in the first person plural. (For example, "we go" is mir gangad instead of Standard German's wir gehen.)

- As in other Alemannic dialects, the pronunciation of "s" before "t" and "p" is [ʃ] (For example, Fest ("party"), is pronounced as Feschd.)

- The voice-onset time for plosives is about halfway between where it would be expected for a clear contrast between voiced and unvoiced-aspirated plosives. This difference is most noticeable on the unvoiced plosives, rendering them very similar to or indistinguishable from voiced plosives:

| "t" to "d" | "p" to "b" | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard High German (SHG) | Swabian | Standard High German (SHG) | Swabian |

| Tasche (bag) | Dasch | putzen (to clean) | butza |

| Tag (day) | Dag | Papa (dad) | Baba |

- One obvious feature is the addition of the diminutive "-le" suffix on many words in the German language. With the addition of this "-le" (pronounced /lə/), the article of the noun automatically becomes "das" in the German language, as in Standard High German (SHG). The Swabian "-le" is the same as SHG "-lein" or "-chen", but is used, arguably, more often in Swabian. A small house (SHG: Haus) is a Häuschen or Häuslein in SHG, a Haisle in Swabian. In some regions, "-la" for plural is used. (For example, Haisle may become Haisla, Spätzle becomes Spätzla.) Many surnames in Swabia are also made to end in "-le".

| SHG | Swabian |

|---|---|

| Zug (train) | Zigle |

| Haus (house) | Haisle |

| Kerl (guy) | Kerle |

| Mädchen (girl) | Mädle |

| Baum (tree) | Baimle |

- Articles (SHG: der, die, das) are often pronounced as "dr", "d" and "s" ("s Haus" instead of "das Haus").

- The "ch" is sometimes omitted or replaced. "ich", "dich" and "mich" may become "i", "di" and "mi".

- Vowels:

| SHG | Swabian | Example (SHG = Swabian) |

English |

|---|---|---|---|

| short a [a] | [a] | machen = macha | to make |

| long a [aː] | [ɔː] | schlafen = schlofa | to sleep |

| short e [ɛ] | [e] | Mensch, fest = Mentsch, fescht | person, steady |

| [ɛ] | Fest = Fäscht | festival | |

| long e [eː] | [ɛa̯] | leben = läaba | to live |

| short o [ɔ] | [ɔ] | Kopf = Kopf | head |

| long o [oː] | [aʊ̯] | hoch, schon = hau, schau | high, already |

| short ö [œ] | [e] | kennen, Köpfe = kenna, Kepf | to know, heads (pl) |

| long ö [øː] | [eː] | schön = schee | beautiful |

| short i [ɪ] | [e] | in = en | in |

| long i (ie) [iː] | [ia̯] | nie = nia | never |

| short ü [ʏ] | [ɪ] | über = iber | over |

| long ü [yː] | [ia̯] | müde = miad | tired |

| short u [ʊ] | [ɔ] | und = ond | and |

| long u [uː] | [ua̯] | gut = guat | good |

| ei [aɪ̯] | [ɔa̯], [ɔɪ̯][lower-alpha 1] | Stein = Schdoa/Schdoi | stone |

| [a̯i][lower-alpha 2] | mein = mei | my | |

| au [aʊ̯] | [aʊ̯][lower-alpha 3] | laufen = laofa | to run |

| [a̯u][lower-alpha 4] | Haus = Hous | house | |

| eu [ɔʏ̯] | [a̯i], [ui̯] | Feuer = Feijer/Fuijer | fire |

In many regions, the Swabian dialect is spoken with a unique intonation that is also present when native speakers speak in SHG. Similarly, there is only one alveolar fricative phoneme /s/, which is shared with most other southern dialects. Most Swabian-speakers are unaware of the difference between /s/ and /z/ and do not attempt to make it when they speak Standard German.

The voiced plosives, the post-alveolar fricative, and the frequent use of diminutives based on "l" suffixes gives the dialect a very "soft" or "mild" feel, often felt to be in sharp contrast to the harder varieties of German spoken in the North.

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal/ Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p b | t d | k ɡ | ||||

| Affricate | b̥f | d̥s | (d̥ʃ) | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | ||||

| Fricative | f v | s | ʃ | (ç) | x (ɣ) | ʁ | (ʕ) h |

| Approximant | l | j |

- Voiceless plosives are frequently aspirated as [pʰ tʰ kʰ].

- Voiced consonants /b d ɡ v/ can be devoiced as [b̥ d̥ ɡ̊ v̥] after a voiceless consonant.

- Allophones of /ʁ/ are often a pharyngeal or velar sound, or lowered to an approximant [ʕ] [ɣ] [ʁ̞].

- [ç] occurs as an intervocalic allophone of /x, h/.[10]

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | ɪ i | iː | u | uː | ||

| Close-mid | e | eː | ə | o | oː | |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɛː | (ɐ) | ʌ ɔ | ɔː | |

| Open | a | aː | ||||

- /a/ preceding a nasal consonant may be pronounced as [ɐ]. When /a/ is lengthened, before a nasal consonant, realized as [ʌː].

- /ə/ preceding an /r/ can be pronounced as [ʌ].[11]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | iə | uə, ui | |

| Mid | eə | əi | əu, ɔe |

| Open | ae | ao |

Classification and variation

Swabian is categorized as an Alemannic dialect, which in turn is one of the two types of Upper German dialects (the other being Bavarian).

The Swabian dialect is composed of numerous sub-dialects, each of which has its own variations. These sub-dialects can be categorized by the difference in the formation of the past participle of 'sein' (to be) into gwäa and gsei. The Gsei group is nearer to other Alemannic dialects, such as Swiss German. It can be divided into South-East Swabian, West Swabian and Central Swabian.[12]

Danube Swabian dialects

The Danube Swabians from Hungary, Romania, and former Yugoslavia have been speaking several different Swabian dialects, called locally Schwowisch, some being similar to the original Swabian dialect, but also the Bavarian dialect, mostly with Palatine and Hesse mixed dialects.[13] In this regard, the Banat Swabians speak the Banat Swabian dialect.

Recognition in mass media

The Baden-Württemberg Chamber of Commerce launched an advertising campaign with the slogan "Wir können alles. Außer Hochdeutsch." which means "We can [do] everything. Except [speak] Standard German" to boost Swabian pride for their dialect and industrial achievements.[14] However, it failed to impress Northern Germans[15] and neighboring Baden. Dominik Kuhn (Dodokay) became famous in Germany with Swabian fandub videos,[16] dubbing among others Barack Obama with German dialect vocals and revised text.[17] In the German dubbing of the 2001 movie Monsters Inc., the Abominable Snowman, played by John Ratzenberger in the original English version and Walter von Hauff in the German version, speaks in the Swabian dialect.[18][19]

Swabian dialect writers

- Sebastian Sailer (1714–1777)

- August Lämmle (de) (1876–1962)

- Josef Eberle (as Sebastian Blau) (de) (1901–1986)

- Thaddäus Troll (1914–1980)

- Hellmut G. Haasis (born 1942)

- Peter Schlack (de) (born 1943)

- Gerhard Raff (born 1946)

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 "Swabian". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- ↑ Hyazinth Wäckerle: Gau! Stau! Bleiba lau! Gedichte in schwäbischer Mundart. Augsburg, 1875, p. 6 (Google Books)

- ↑ Swabian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ↑ "Swabian". IANA language subtag registry. 29 July 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ↑

not included e.g. in:

- Hermann Niebaum, Jürgen Macha, Einführung in die Dialektologie des Deutschen, 3rd ed, 2014, p. 252: "Das Westobd. [= Westoberdeutsche] zerfällt in Alemannisch, Schwäbisch, Südfränkisch und Ostfränkisch."

- Peter von Polenz, Geschichte der deutschen Sprache, 10th ed., 2009, p. 26 with a map having the dialect area of Alemannisch and Schwäbisch as "Westoberdeutsch", and p. 23: "[...] in den südlichsten Dialekten Alemannisch, Schwäbisch, Bairisch und Ostfränkisch, die zusammen das Oberdeutsche bilden."

- ↑ [http://www.goethe.de/ins/ge/prj/dig/his/lig/deindex.htm%22Geschichte+der+deutschen+Siedler+im+Kaukasus+–+Leben+in+Georgien+–+Goethe-Institut+2019%22.+www.goethe.de.+Retrieved+30+January+2019.

- ↑ Gehl, Hans. "Donauschwäbische Dialekte, 2014". www.sulinet.hu (in German). Sulinet Program Office (Hungary) in cooperation with the Ministry of Education. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ↑ Schönstes schwäbisches Wort, Großer Vorsprung für Schwabens kleinste Einheit Archived 2013-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, Jan Sellner 09.03.2009, Stuttgarter Nachrichten

- ↑ Swabian dictionary Archived 2015-06-03 at the Wayback Machine at website of Südwestrundfunk Ein Fall für B.A.R.Z.

- ↑ Russ, Charles V. J. (1990). Swabian. The Dialects of Modern German: a Linguistic Survey: Routledge. pp. 337–363.

- ↑ Frey, Eberhard (1975). Stuttgarter Schwäbisch: Laut- und Formenlehre eines Stuttgarter Idiolekts. Deutsche Dialektgeographie, 101: Marburg: Elwert. pp. 8–45.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ Noble, Cecil A. M. (1983). Modern German dialects New York [u.a.], Lang, p. 63.

- ↑ "Language & Dialect(s)".

- ↑ Baden-Württemberg Chamber of Commerce Archived 2007-11-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Diskriminiteer Dialekt Armes Süddeutsch FAZ 2013

- ↑ Graham, Dave (2010-10-14). "Star Wars dub sends jobbing ad man into orbit". Reuters.

- ↑ Barack Obama Schwäbisch – Rede Berlin 2013 – dodokay

- ↑ Monsters, Inc. (2001) – IMDb, retrieved 2020-11-12

- ↑ "Deutsche Synchronkartei | Filme | Die Monster AG". www.synchronkartei.de. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

Literature

- Streck, Tobias (2012). Phonologischer Wandel im Konsonantismus der alemannischen Dialekte Baden-Württembergs : Sprachatlasvergleich, Spontansprache und dialektometrische Studien (in German). Stuttgart: Steiner. ISBN 978-3-515-10068-7.

- Cercignani, Fausto (1979). The consonants of German : synchrony and diachrony. Milano: Cisalpino-Goliardica. LCCN 81192307.