Schluckbildchen; from German, which means literally "swallowable pictures", are small notes of paper that have a sacred image on them with the purpose of being swallowed. They were used as a religious practice in the folk medicine throughout the eighteenth to twentieth century, and were believed to possess curative powers. Frequently found in the "spiritual medicine chests" of devout believers at that time, by swallowing them they wished to gain these curative powers. They are to be distinguished from Esszettel; from German, meaning "edible notes of paper", the latter only having text written on them.

Variations

Esszettel

Esszettel had either adages, names of saints, prayers or bible verses written on them, usually in the shortened form of sigils. Occasionally, red paper was used. In Holstein, for example, feverish people were given slips saying „Fieber bleib aus / N.N. ist nicht zu Haus“ (fever stay away, N.N. is not at home). In Protestant regions like Württemberg, East Frisia, Oldenburg or Hamburg, people symbolically consumed their own illness by eating a paper note that had their name, date of birth or some kind of phrase written on it. The slip was then stuck into a piece of bread or fruit, and the sick person ate it.[1]

Handwritten or printed Esszettel[2] were even used to cure animals, from illnesses like rage disease or numbness (also called Fresszettel). The Sator square was thought to help against Rabies. In the Upper Bavarian region of Isarwinkel farmers treated their livestock with Esszettel to cure anthrax.

Unfortunately, there are not many remains of such Esszettel today, one of the reasons lying in the fact that the church institutions had mostly seen Esszettel as pure superstition. Hints as to how they looked like can be found in literature, where triangle shaped Esszettel are mentioned, those not only with the purpose of being swallowed, though. The triangle shaped Esszettel had words or phrases printed on them that were repeated over and over, losing one or two letters with each repetition. That way, the sick person wished to overcome the illness bit by bit.[1]

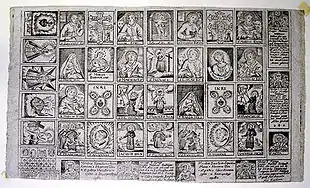

Esszettel that have survived to the present day are usually remains of mass-produced stock which were sold on pilgrimage markets. These types of Esszettel were printed on stamp-like sheets of paper. They were either labeled identically or varied in a certain pattern. The latter version was called Lukaszettel, and one of the printing plates used to print Lukaszettel has been preserved. Sometimes, Esszettel were printed on both sides, the back page complementing the front page. These are considered to be the oldest types of Esszettel.

Schluckbildchen

Schluckbildchen had a square, rectangular or round shape and a feed size of 5 to 20 mm. So they were the smallest form of devotional art design. Small pictures of the 19th century were partly bigger, like the version that was produced in Einsiedeln (32x22 mm). Also Schluckbildchen were produced on light sheets of paper; one sheet could hold 130 pieces. Both possible were series of one theme as well as different themes which would always have the same style. Schluckbildchen can be detected after the middle age.[3] Up to the 19th century copper engraving printings were most likely, including some notes (for example in Mariazell) which were produced with a woodcarving technique. Later, colour printing was used; in the 20th century also photomechanical reproduction of old artworks.

Schluckbildchen often show the Virgin Mary as a picture of mercy in a specific pilgrimage location, sometimes other saints or portrayals from Christian iconography, like the Nomen sacrum or Titulus INRI. Usually, under the theme an inscription is placed naming the location of pilgrimage or the saint that is portrayed. Frequently, someone made the effort also to put on details of the devotional art design. The symmetry of the rectangular, triangular, diamond-shaped, round or elliptical-shaped frame elements concentrated the effect of the picture on the central theme. Also effects like rays of light as well as the floating on clouds put emphasise on the transcendental character of the picture.[4]

Producer and sales

Esszettel were sold not only by merchants in pilgrimage locations, but also by charlatans. It is passed on that a charlatan was travelling through Saxony in 1898, who gave Sympathiezettelchen (literal translation: sympathy notes) that were written in unreadable words, for an optional prize from 0.30 up to one Deutsche Mark to ill people to eat. Esszettel were also prescribed by a Saxon quack in 1913, known under the name “the Reinsdorf miner”.

In former times, Schluckbildchen were sold in all pilgrimage locations. Producers were (among others):

- F. Gutwein, Augsburg

- J. M. Söckler, Munich

- F. Pischel, Linz

- Jos. Nowohradsky, Graz

- Frères Benziger, Einsiedeln.

Brandzettel (literal translation: notes of fire), which were used for the recovery of animals, were available at Franciscan in Tölz. Schluckbildchen were from time to time a flourishing business of some monasteries.[5] At the beginning of the seventies in the 19th century, “Schluckbildchen” were still sold in Mariazell, Naples, and Sata Maria del Carmine in Florence. Schluckbildchen of Our Dear Virgin of Everlasting Aid were sold from Rome to the whole world.[6] Ethnologist Dominik Wunderlin, department manager at the Museum der Kulturen Basel, reported in 2005 that a woman`s monastery in Bavaria, which was not named in that connection, was still giving away Schluckbildchen at the entrance gate.[7]

Use

As the terms Schluckbildchen and Esszettel suggest, their main medical purpose was of spiritual nature, also called “gratia medicinalis” during the Baroque period.[8] The paper pills were either soaked in water, dissolved or added to dishes, in order to then be swallowed by the sick person. The ingestion of little pictures can be seen as a primitive and unmediated form of taking possession of the embodiment of the saint's curative power (or whoever was depicted). Both the ritual effort that was made to grasp the true meaning of the cult image, but also the memory of the pilgrimage adventure the sick person associated with the Schluckbildchen, increased the miraculous effect. That held true despite the fact that many Schluckbildchen were hard to decipher and written in poor Latin. What remains unclear until today is the question, whether or not the consumption of Schluckbildchen was in any way connected to the practices of the Eucharist or the Sacramental bread.

In rarer cases, Schluckbildchen were used as letters of protection or as religious amulets common at that time (e.g. Wettersegen or Breverl). Furthermore, they were used as decorations for gingerbread and other pastries.

If nothing else was at hand, even holy images used in devotions were swallowed; either as a whole or torn apart and soaked in water. Lastly, it was quite common to eat images taken from Calendars of saints.

Schluckbildchen were used in either practices of organized religion and folk religion.[9] On August 3, 1903, the Roman Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith announced that as long as there were no superstitious practices involved, the use of Esszettel was officially granted.[10] According to Eduard Stemplinger on the other hand, on July 29 the same congregation had already decided that swallowing water-soaked paper notes with Madonna images printed on them in order to heal illnesses certainly did not count as superstition.[11]

Similar objects

Esszettel were known as Fieberzettel (literal translation: fever notes) already in antiquity. In Carolingian Indiculus superstitionum, there was talk about a consumption of an image of deity which was baked in bread. In late Roman medicine the ash of burnt papyrus sheets („charta combusta“) was used as an ingredient for ointment and for orally and rectally applied medicine. Those notes were supposed to have a healing effect both labelled and unlabelled.

Resembling qualities to the Esszettel also has “fever altar bread” which was given away by the minorites in the end of the 18th century. Wafe was also used as healing medicine in the turn of the 15th century as it was described in the poem Bluemen der tugent by the Tyrolean Hans Vintler: „Vil di wellen auf oblat schreiben / und das Fieber damit vertreiben“.

Further examples are the grated clay Madonna , which were common up to the 20th century, and from which you grated the surface to eat. For the same purpose water was used, with which relics and resembling objects were cleaned.[11] Also the “protecting notes”, which were known in the Thirty Years` War as art from Passau, were also swallowed while facilitating ritual rules.

A printing plate, which was found in the second decade of the 19th century in Eastern Mongolia, proves that also in that culture “eating notes” were used.[12] In small squares from approx. 34x29 mm the printing plate contains several Tibetan spells that enclose also the connected purpose. Apparently, it originated from Tibetan Lamaistic folk medicine and was probably used by a Lamaistic migrant medical practitioner. Depending on the indication those notes had several instructions for use, e.g. “Eat when having flu” or “Eat nine when having stomach ache”.

From Uganda it is known that in the end of the 1990s followers of a famous Christian charismatic preacher and magic healer soaked his photographs in water and drank from it in order to swallow up parts of his healing power.[13]

References

- 1 2 Richter, Sp. 43

- ↑ „Fresszettel“ im Ortsmuseum Rüthi-Büchel, St. Gallen, Schweiz

- ↑ Adolph Franz: Die kirchlichen Benediktionen im Mittelalter. Bd. 2, S. 454, Anm. 2. Freiburg/Br. 1909. Zitiert in Christoph Kürzeder: Als die Dinge heilig waren. Gelebte Frömmigkeit im Zeitalter des Barock. S. 130. Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2005, ISBN 3-7954-1769-4

- ↑ Schneegass, S. 29

- ↑ Margarete Ruff: Zauberpraktiken als Lebenshilfe: Magie im Alltag vom Mittelalter bis heute, S. 154. Campus, Frankfurt/Main 2003, ISBN 3-593-37380-7

- ↑ Richter, Sp. 44

- ↑ Dominik Wunderlin: Volksfrömmigkeit in der Vergangenheit. Exemplarisch dargestellt an Objekten der Sammlung Dr. Edmund Müller

- ↑ Wolfgang Brückner: Eßzettel. In Lexikon für Theologie und Kirche. Bd. 3, Sp. 894. Herder, Freiburg 1993, ISBN 3-451-22003-2.

- ↑ Lenz Kriss-Rettenbeck: Bilder und Zeichen religiösen Volksglaubens. S. 45. Callwey Verlag, München 1963

- ↑ Philipp Schmidt: Frömmigkeit auf Abwegen (=Morus-Kleinschriften, Nr. 32), S. 7. Morus-Verlag, Berlin 1955. Zitiert bei Richter, Sp. 47.

- 1 2 Eduard Stemplinger: Antike und moderne Volksmedizin (= Das Erbe der Alten 2; 10), S. 65. Dieterich, Leipzig 1925.

- ↑ Walther Heissig: Heilung durch Zettelschlucken. In Walther Heissig, Claudius C. Müller (Hrsg.): Die Mongolen. Bd. 2. Pinguin-Verlag, Innsbruck 1989, ISBN 3-7016-2297-3

- ↑ Heike Behrend: Photo Magic: Photographs in Practices of Healing and Harming in East Africa. Journal of Religion in Africa 33, 22 (August 2003): 129–145, ISSN 0022-4200

Literature

- Franz Eckstein: Essen. In: Eduard Hoffmann-Krayer, Hanns Bächtold-Stäubli (Hrsg.): Handwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens. Band 2, De Gruyter, Berlin, New York, NY 1987, 2000, ISBN 3-11-011194-2 (Ausgabe 1987) / ISBN 3-11-016860-X (Ausgabe 2000), Sp. 1055–1058.

- Josef Imbach: Marienverehrung zwischen Glaube und Aberglaube. S. 185. Patmos, Düsseldorf 2008, ISBN 978-3-491-72528-7

- Erwin Richter: Eßzettel, in: Reallexikon zur Deutschen Kunstgeschichte, Bd. 6, 1968, Sp. 42–48

- Christian Schneegass: Schluckbildchen. Ein Beispiel der „Populärgraphik“ zur aktiven Aneignung. In: Volkskunst Zeitschrift für volkstümliche Sachkultur, Bilder, Zeichen, Objekte. Callwey, München 1983. ISSN 0343-7159 Nummer 6.