Samuel J. Randall | |

|---|---|

Randall c. 1865–80 | |

| 29th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives | |

| In office December 4, 1876 – March 3, 1881 | |

| Preceded by | Michael C. Kerr |

| Succeeded by | J. Warren Keifer |

| Leader of the House Democratic Caucus | |

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 3, 1871 | |

| Preceded by | George S. Houston (1861) |

| Succeeded by | William E. Niblack (1873) |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania | |

| In office March 4, 1863 – April 13, 1890 | |

| Preceded by | William Eckart Lehman |

| Succeeded by | Richard Vaux |

| Constituency | 1st district (1863–75) 3rd district (1875–90) |

| Member of the Pennsylvania Senate from the 1st district | |

| In office 1857–1859 | |

| Preceded by | Isaac Nathaniel Marselis |

| Succeeded by | Richardson L. Wright |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Samuel Jackson Randall October 10, 1828 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | April 13, 1890 (aged 61) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

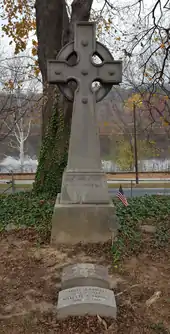

| Resting place | Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Political party | Whig Democratic |

| Spouse | Fannie Agnes Ward |

| Occupation | Politician |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States Union |

| Branch/service | Union Army |

| Years of service | 1861; 1863 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Samuel Jackson Randall (October 10, 1828 – April 13, 1890) was an American politician from Pennsylvania who represented the Queen Village, Society Hill, and Northern Liberties neighborhoods of Philadelphia from 1863 to 1890 and served as the 29th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1876 to 1881. He was a contender for the Democratic Party nomination for President of the United States in 1880 and 1884.

Born in Philadelphia to a family active in Whig politics, Randall shifted to the Democratic Party after the Whigs' demise. His rise in politics began in the 1850s with election to the Philadelphia Common Council and then to the Pennsylvania State Senate for the 1st district. Randall served in a Union cavalry unit in the American Civil War before winning a seat in the federal House of Representatives in 1862. He was re-elected every two years thereafter until his death. The representative of an industrial region, Randall became known as a staunch defender of protective tariffs designed to assist domestic producers of manufactured goods. While often siding with Republicans on tariff issues, he differed with them in his resistance to Reconstruction and the growth of federal power.

Randall's support for smaller, less centralized government raised his profile among House Democrats, and they elevated him to Speaker in 1876. He held that post until the Democrats lost control of the House in 1881, and was considered a possible nominee for president in 1880 and 1884. Randall's support for high tariffs began to alienate him from most Democrats, and when that party regained control of the House in 1883, he was denied another term as Speaker. Randall continued to serve in Congress as chair of the Appropriations Committee. He remained a respected party leader but gradually lost influence as the Democrats became more firmly wedded to free trade. Worsening health also curtailed his power until his death in 1890.

Early life and family

Randall was born on October 10, 1828, in Philadelphia, the eldest son of Josiah and Ann Worrell Randall.[1] Three younger brothers soon followed: William, Robert, and Henry.[2] Josiah Randall was a leading Philadelphia lawyer who had served in the state legislature in the 1820s.[3] Randall's paternal grandfather, Matthew Randall, was a judge on the Pennsylvania Courts of Common Pleas and county prothonotary in that city in the early 19th century.[4] His maternal grandfather, Joseph Worrell, was also a prominent citizen, active in politics for the Democratic Party during Thomas Jefferson's presidency.[2] Josiah Randall was a Whig in politics, but drifted into the Democratic fold after the Whig Party dissolved in the 1850s.[5]

When Randall was born, the family lived at Seventh and Walnut Streets in what is now Center City Philadelphia.[2] Randall was educated at the University Academy, a school affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania.[1] On completing school at age 17, he did not follow his father into the law, but instead took a job as a bookkeeper with a local silk merchant.[6] Shortly thereafter, he started a coal delivery business and, at age 21, became a partner in a scrap iron business named Earp and Randall.[7]

Two years later, in 1851, Randall married Fannie Agnes Ward, the daughter of Aaron and Mary Watson Ward of Sing Sing, New York.[8] Randall's new father-in-law was a major general in the New York militia and had served in Congress as a Jacksonian Democrat for several terms between 1825 and 1843.[9] Randall and Fannie went on to have three children: Ann, Susan, and Samuel Josiah.[8]

Local politics and military service

In 1851, Randall assisted his father in the election campaign for a local judge.[7] The judge, a Whig, was elected despite considerable opposition from a candidate of the nativist American Party (commonly called the "Know-Nothing Party").[7] The strength of this group, combined with the Whigs' declining fortunes, led Samuel Randall to call himself an "American Whig" when he ran for Philadelphia Common Council the following year.[7] He was elected, holding office for four one-year terms from 1852 to 1856.[7] The period was one of significant change in Philadelphia's governance, as all of Philadelphia County's townships and boroughs were consolidated into one city in 1854.[10]

As the Whig Party fell apart, Randall and his family became Democrats.[6] Josiah Randall was friendly with James Buchanan, a Pennsylvania Democrat then serving as the United States' envoy in Great Britain.[11] Both Randall and his father attended the Democratic National Convention in 1856 to work for Buchanan's nomination for president, which was successful.[12] When, in 1858, a vacancy occurred in Randall's state Senate district, he ran for election (as a Democrat) for the remainder of the term, and was elected.[12] Still only 30 years old, Randall had risen rapidly in politics. Much of his term in the state Senate was spent dealing with the incorporation of street railway companies, which he believed would benefit his district.[13] Randall also supported legislation to reduce the power of banks, a policy that he would continue to advocate for his entire political career.[13] In 1860, he ran for election to a full term in the state Senate while his brother Robert ran for a seat in the state House of Representatives.[14] Ignoring their father's advice that it meant "too much Randall on the ticket", both brothers were unsuccessful.[14]

In 1861, the Civil War began as eleven Southern states seceded from the Union to form the Confederate States of America. Randall joined the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry in May of that year as a private.[15] The unit was stationed in central Pennsylvania and eastern Virginia during Randall's 90-day enlistment, but saw no action during that time.[15] In 1863, he re-joined the unit, this time being elected captain.[14] The First Troop was sent back to central Pennsylvania during the Gettysburg campaign that summer, when Confederate forces under Robert E. Lee invaded Pennsylvania.[14] He served as provost marshal at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania in the days before the battle there, and had the same role at Columbia, Pennsylvania during the battle, but did not see combat.[15] As historian Albert V. House explained, "[h]is military career was respectable, but far from arduous, most of his duties being routine reconnoitering which seldom led him under fire."[15]

House of Representatives

Election to the House

In 1862, before rejoining his cavalry unit, Randall was elected to the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania's 1st congressional district.[16] The city had been gerrymandered by a Republican legislature to create four solidly Republican districts, with the result that as many Democrats as possible were lumped into the 1st district.[15] Gaining the Democratic nomination was, thus, tantamount to election; Randall defeated former mayor Richard Vaux for their party's endorsement and won easily over his Republican opponent, Edward G. Webb.[17] He won with the help of William "Squire" McMullen, the Democratic boss of the fourth ward, who would remain a lifelong Randall ally.[18]

Under the congressional calendar of the 1860s, members of the 38th United States Congress, elected in November 1862, did not begin their work until December 1863. Randall arrived that month, after being discharged from his cavalry unit, to join a Congress dominated by Republicans.[19] As a member of the minority, Randall had little opportunity to author legislation, but quickly became known as a hard-working and conscientious member.[16] James G. Blaine, a Republican also first elected in 1862, later characterized Randall as "a strong partisan, with many elements of leadership. He ... never neglects his public duties, and never forgets the interests of the Democratic Party."[20]

Randall was known as a friend to the manufacturers in his district, especially as it concerned protective tariffs.[21] Despite being in the minority, Randall spoke often in defense of his constituents' interests.[22] As House described him,

He had a tongue that could snap out sarcastic quips with lightning speed. His voice was pitched rather high, and in moments of excitement, its metallic ring approached a shrill screech. His countenance was usually very attractive ... but this face became a thundercloud when he was in a defiant mood.[22]

With his party continually in the minority, Randall gained experience in the functioning of the House, but his tenure left little evidence in the statute book.[22] He attracted little attention, but kept his constituents happy and was repeatedly reelected.[23]

War and Reconstruction

When the 38th Congress convened in December 1863, the Civil War was approaching its end. Randall was a War Democrat, sometimes siding with his Republican colleagues to support measures in pursuit of victory over the Confederates.[23] When a bill was proposed to allow President Abraham Lincoln to promote Ulysses S. Grant to lieutenant general, Randall voted in favor, unlike most in his party.[23] He voted with the majority of Democrats, however, to oppose allowing black men to serve in the Union Army.[24]

When it came to political plans for the post-war nation, he was strictly opposed to most Republican-proposed measures.[25] Republicans proposed the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1865, which would abolish slavery, and Randall spoke against it.[25] Claiming opposition to slavery, Randall said his objections stemmed instead from a belief that the amendment was "a beginning of changes in the Constitution and the forerunner of usurpation".[23] After Andrew Johnson became president following Lincoln's assassination, Randall came to support Johnson's policies for Reconstruction of the defeated South, which were more lenient than those of the Republican majority in Congress.[26] In 1867, the Republicans proposed requiring an ironclad oath from all Southerners wishing to vote, hold office, or practice law in federal courts, making them swear they had never borne arms against the United States.[27] Randall led a 16-hour filibuster against the measure; in spite of his efforts, it passed.[27]

Randall began to gain prominence in the small Democratic caucus by opposing Reconstruction measures. His delaying tactics against fellow Pennsylvanian Thaddeus Stevens's military Reconstruction bill in February 1867 kept the bill from being considered for two weeks—long enough to prevent it from being voted on until the next session.[28] He likewise spoke against what would become the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.[29] Although he opposed the amendment, Randall did favor the idea behind part of it: section 4, which guarantees that Congress may not repudiate the federal debt, nor may it assume debts of the Confederacy, nor debt that the individual Confederate states incurred during the rebellion.[30] Many Republicans claimed that if the Democrats were to regain power, they would do exactly that, repudiating federal debt and assuming that of the rebels.[31] Despite disagreement on other facets of Reconstruction, Randall stood firmly with the Republicans (and most Northern Democrats) on the debt.[31]

As impeachment proceedings began against President Johnson, Randall became one of his leading defenders in the House.[32] Once the House determined to impeach Johnson, Randall worked to direct the investigation to the Judiciary Committee, rather than a special committee convened for the purpose, which he believed would be stacked with pro-impeachment members.[32] His efforts were unsuccessful, as were his speeches in favor of the president: Johnson was impeached by a vote of 128 to 47.[33] Johnson was not convicted after his Senate trial, and Randall remained on good terms with him after the president left office.[30]

Financial legislation

With Grant, a Republican, elected president in 1868, and the 41st Congress as Republican-dominated as its immediate predecessors, Randall faced several more years in the minority. He served on the Banking and Currency Committee and began to focus on financial matters, resuming his long-standing policy against the power of banks.[31] This placed Randall in the growing fight over the nature of the nation's currency—those who favored the gold-backed currency were called "hard money" supporters, while the policy of encouraging inflation through coining silver or issuing dollars backed by government bonds ("greenbacks") was known as "soft money".[34] Although he believed in a gold-backed dollar, Randall was friendly to greenbacks; in general, he favored allowing the amount of currency to remain constant, while replacing bank-issued dollar bills with greenbacks.[34] He also believed the federal government should sell its bonds directly to the public, rather than selling them only to large banks, which then re-sold them at a profit.[35] He was unsuccessful in convincing the Republican majority to adopt any of these measures.[31]

Randall worked with Republicans to shift the source of federal funds from taxes to tariffs.[36] He believed the taxation of alcohol spread the burdens of taxation unfairly, especially as concerned his constituents, who included several distillers.[36] He also believed the income tax, first enacted during the Civil War, was being administered unfairly, with large refunds often accruing to powerful business interests.[36] On this point, Randall was successful, and the House accepted an amendment that required all cases for refunds over $500 to be tried before a federal district court.[36] He also worked toward the elimination of taxation on tea, coffee, cigars, and matches, all of which Randall believed fell disproportionately on the poor.[37] Relief from taxation made these items cheaper for the average American, while increasing reliance on tariffs helped the industrial owners and workers in Randall's district, as it made foreign products more expensive.[38]

Tariff legislation generally found favor with Randall, which put him more often in alliance with Republicans than Democrats.[39] In the late 1860s and early 1870s, Randall worked to raise tariffs on a wide variety of imported goods.[38] Even so, he sometimes differed with the Republicans when he believed the tariff proposed was too high; biographer Alfred V. House describes Randall's attitude as supporting "higher tariff rates ... largely because he believed that the benefits of such high rates were passed on to the labor population."[40] In 1870, he opposed the pig iron tariff as too high, against the wishes of fellow Pennsylvanian William "Pig Iron" Kelley.[41] Randall called his version of protectionism "incidental protection": he believed tariffs should be high enough to support the cost of running the government, but applied only to those industries that needed tariff protection to survive foreign competition.[42]

Appropriations and investigations

While the Democrats were in the minority, Randall spent much of his time scrutinizing the Republicans' appropriations bills.[43] During the Grant administration, he questioned thousands of items in the appropriation bills, often gaining the support of Republicans in excising expenditures that were in excess of the departments' needs.[44][21] He proposed a bill that would end the practice, common at the time, of executive departments spending beyond what they had been appropriated, then petitioning Congress to retroactively approve the spending with a supplemental appropriation; the legislation passed and became law.[44] The supplemental appropriations were typically rushed through at the end of a session with little debate.[44] Reacting to the large grants of land given to railroads, he also sought unsuccessfully to ban all land grants to private corporations.[45]

Investigating appropriations led Randall to focus on financial impropriety in Congress and the Grant administration.[21] The most famous of these was the Crédit Mobilier scandal.[21] In this scheme, the Union Pacific Railroad bankrupted itself by overpaying its construction company, the Crédit Mobilier of America.[46] Crédit Mobilier was owned by the railroad's principal shareholders and, as the investigation discovered, several congressmen also owned shares that they had been allowed to purchase at discounted prices.[46] Randall's role in the investigation was limited, but he proposed bills to ban such frauds and sought to impeach Vice President Schuyler Colfax, who had been implicated in the scandal.[46] Randall was involved with the investigation of several other scandals, as well, including tax fraud by private tax collection contractors (known as the Sanborn incident)[47] and fraud in the awarding of postal contracts (the star route scandal).[21]

Randall was caught on the wrong side of one scandal in 1873 when Congress passed a retroactive pay increase.[21] On the last day of the term, the 42nd Congress voted to raise its members' pay by 50%, including a raise made retroactive to the beginning of the term.[48] Randall voted for the pay raise, and against the amendment that would have removed the retroactive provision.[49] The law, later known as the Salary Grab Act, provoked outrage across the country.[48] Randall defended the Act, saying that an increased salary would "put members of Congress beyond temptation" and reduce fraud.[50] Seeing the unpopularity of the Salary Grab, the incoming 43rd Congress repealed it almost immediately, with Randall voting for repeal.[51]

Rise to prominence

Democrats remained in the minority when the 43rd Congress convened in 1873. Randall continued his opposition to measures proposed by Republicans, especially those intended to increase the power of the federal government.[52] That term saw the introduction of a new civil rights bill with farther-reaching ambitions than any before it. Previous acts had seen the use of federal courts and troops to guarantee that black men and women could not be deprived of their civil rights by any state.[53] Now Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts proposed a new bill, aimed at requiring equal rights in all public accommodations.[53] When Sumner died in 1874, his bill had not passed, but others from the radical wing of the Republican Party, including Representative Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts, continued to work for its enactment.[54]

Randall stood against this measure, as he had against nearly all Reconstruction laws.[21] A lack of consensus delayed the bill from coming to a vote until the lame-duck session beginning in December 1874.[55] By that time, disillusionment with the Grant administration and worsening economic conditions had translated into a Democratic victory in the mid-term elections.[55] When the 44th Congress gathered in March 1875, the House would have a Democratic majority for the first time since the Civil War.[55] In the meantime, the outgoing Republicans made one last effort to pass Sumner's civil rights bill; Randall and other Democrats immediately used parliamentary maneuvers to bring action to a stand-still, hoping to delay passage until the Congress ended.[55] Randall led his caucus in filibustering the bill, at one point remaining on the floor for 72 hours.[52] In the end, the Democrats peeled away some Republican votes, but not enough to defeat the bill, which passed by a vote of 162 to 100.[56] Despite the defeat, Randall's filibuster increased his prominence in the eyes of his Democratic colleagues.[57]

As Democrats took control of the House in 1875, Randall was considered among the candidates for Speaker of the House.[58] Many in the caucus hesitated, however, believing Randall to be too close to railroad interests and uncertain on the money question.[59] His leadership in the Salary Grab may have harmed him, as well.[60] Randall was also occupied by an intra-party battle with William A. Wallace for control of the Pennsylvania Democratic Party.[61] Wallace, who had been elected to the United States Senate in 1874, was weakened by rumors that he had taken bribes from the railroads while a member of the State Senate.[62] Randall wanted control of the Democratic machine statewide, and the Wallace faction's vulnerability on the bribery rumors provided the opportunity.[63] In January 1875, he had friends in the state legislature begin an investigation into Wallace's clique, which ultimately turned state Democratic leaders against the senator.[64] At the state Democratic convention in September 1875, Randall (with the help of his old ally, Squire McMullen) triumphed, putting his men in control of the state party.[65]

In the meantime, the divisions in the state party proved ruinous for Randall's chances at the Speaker's chair.[66] Instead, the Democrats decided on Michael C. Kerr of Indiana, who was elected.[66] Randall was instead named chairman of the Appropriations Committee.[52] In that post, he focused on reducing the government's spending, and cut the budget by $30,000,000, despite opposition from the Republican Senate.[21] Kerr's health was fragile, and he was often absent from sessions, but Randall refused to take his place as speaker on a temporary basis, preferring to concentrate on his appropriations work.[67] Kerr and Randall began to work more closely together through 1876, but Kerr died in August of that year, leaving the Speakership vacant once again.[67]

Speaker of the House

Hayes and Tilden

.jpg.webp)

After Kerr's death, Randall was the consensus choice of the Democratic caucus, and was elected to the Speakership when Congress returned to Washington on December 2, 1876.[68] He assumed the chair at a tumultuous time, as the presidential election had just concluded the previous month with no clear winner.[69] The Democratic candidate, Samuel J. Tilden of New York, had 184 electoral votes, just shy of the 185 needed for victory.[70] Rutherford B. Hayes, the Republican, had 163; the remaining 22 votes were in doubt.[70]

Randall spent early December in conference with Tilden while committees examined the votes from the disputed states.[71] The counts of the disputed ballots were inconclusive, with each of the states in question producing two sets of returns: one signed by Democratic officials, the other by Republicans, each claiming victory for their man.[72] By January 1877, with the question still unresolved, Congress and President Grant agreed to submit the matter to a bipartisan Electoral Commission, which would be authorized to determine the fate of the disputed electoral votes.[72]

Randall supported the idea, believing it the best solution to an intractable problem.[73] The bill passed, providing for a commission of five representatives, five senators, and five Supreme Court justices.[74] To ensure partisan balance, there would be seven Democrats and seven Republicans; the fifteenth member was to be a Supreme Court justice chosen by the other four on the commission (themselves two Republicans and two Democrats). Justice David Davis, an independent respected by both parties, was expected to be their choice, but he upset the careful planning by accepting election to the Senate by the state of Illinois and refusing to serve on the commission.[75] The remaining Supreme Court justices were all Republicans and, with the addition of Justice Joseph P. Bradley to the place intended for Davis, the commission had an 8–7 Republican majority.[76] Randall nevertheless favored the compromise, even voting in favor of it in the roll call vote (the Speaker usually does not vote).[77] The commission met and awarded all the disputed ballots to Hayes by an 8–7 party-line vote.[78]

Democrats were outraged, and many demanded that they filibuster the final count in the House.[79] Randall did not commit, but permitted the House to take recesses several times, delaying the decision.[80] As the March 4 inauguration day approached, leaders of both parties met at Wormley's Hotel in Washington to negotiate a compromise. Republicans promised that, in exchange for Democratic acquiescence in the commission's decision, Hayes would order federal troops to withdraw from the South and accept the election of Democratic governments in the remaining "unredeemed" states there.[81] The Democratic leadership, including Randall, agreed and the filibuster ended.[82]

Monetary disputes

Randall returned to Washington in March 1877 at the start of the 45th Congress and was reelected Speaker.[83] As the session began, many in the Democratic caucus were determined to repeal the Specie Payment Resumption Act of 1875.[84] That Act, passed when Republicans last controlled the House, was intended to gradually withdraw all greenbacks from circulation, replacing them with dollars backed in specie (i.e., gold or silver). With the elimination of the silver dollar in 1873, this would effectively return the United States to the gold standard for the first time since before the Civil War. Randall, who had voted against the act in 1875, agreed to let the House vote on its repeal, which narrowly passed.[85] The Senate, still controlled by Republicans, declined to act on the bill.[86]

The attempt at repeal did not end the controversy over silver. Democratic Representative Richard P. Bland of Missouri proposed a bill that would require the United States to buy as much silver as miners could sell the government and strike it into coins, a system that would increase the money supply and aid debtors.[87] In short, silver miners would sell the government metal worth fifty to seventy cents, and receive back a silver dollar. Randall allowed the bill to come to the floor for an up-or-down vote during a special session in November 1877: the result was its passage by a vote of 163 to 34 (with 94 members absent).[lower-alpha 1][88] The pro-silver idea cut across party lines, and William B. Allison, a Republican from Iowa, led the effort in the Senate.[87] Allison offered an amendment in the Senate requiring the purchase of two to four million dollars per month of silver, but not allowing private deposit of silver at the mints.[89] Thus, the seignorage, or difference between the face value of the coin and the worth of the metal contained within it accrued to the government's credit, not private citizens.[89] President Hayes vetoed the bill, but Congress overrode the veto, and the Bland–Allison Act became law.[89]

Potter committee

As the 1880 presidential elections approached, many Democrats remained convinced Tilden had been robbed of the presidency in 1876.[90] In the House, Tilden supporter Clarkson Nott Potter of New York sought an investigation into the 1876 election in Florida and Louisiana, hoping that evidence of Republican malfeasance would harm that party's candidate in 1880.[91] The Democratic caucus, including Randall, unanimously endorsed the idea, and the committee convened in May 1878.[90] Some in the caucus wished to investigate the entire election, but Randall and the more moderate members worked to limit the committee's reach to the two disputed states.[92]

Randall left no doubt about his sympathies when he assigned members to the committee, stacking it with Hayes's enemies from both parties.[93] The committee's investigation had the opposite of the Democrats' intended effect, uncovering telegrams from Tilden's nephew, William Tilden Pelton, offering bribes to Southern Republicans in the disputed states to help Tilden claim their votes.[94] The Pelton telegrams were in code, which the committee was able to decode; Republicans had also sent ciphered dispatches, but the committee was unable to decode them.[94] The ensuing excitement fizzled out by June 1878 as the Congress went into recess.[95]

Reelected Speaker

As the 46th Congress convened in 1879, the Democratic caucus was reduced, but they still held a plurality of seats. The new House contained 152 Democrats, 139 Republicans, and 20 independents, most of whom were affiliated with the Greenback Party.[96] Many of Randall's fellow Democrats differed with him over protectionism and his lack of support for Southern railroad subsidies, and considered choosing Joseph Clay Stiles Blackburn of Kentucky as their nominee for Speaker, instead.[96] Several other Southerners' names were floated, too, as anti-Randall Democrats tried to coalesce around a single candidate; in the end, none could be found and the caucus chose Randall as their nominee with 107 votes out of 152.[96] With some Democrats not yet present, however, the Democrats began to fear that the Republicans and Greenbackers would strike a deal to combine their votes to elect James A. Garfield of Ohio as Speaker.[96] When the time for the vote came, however, Garfield refused to make any compromises with the third-party men, and Randall and the Democrats were able to organize the House once more.[96]

Civil rights and the army

%252C_by_Thomas_Worth.jpg.webp)

Randall's determination to cut spending, combined with Southern Democrats' desire to reduce federal power in their home states, led the House to pass an army appropriation bill with a rider that repealed the Enforcement Acts, which had been used to suppress the Ku Klux Klan.[97] The Enforcement Acts, passed during Reconstruction over Democratic opposition, made it a crime to prevent someone from voting because of his race. Hayes was determined to preserve the law protecting black voters, and he vetoed the appropriation.[97] The Democrats did not have enough votes to override the veto, but they passed a new bill with the same rider. Hayes vetoed this as well, and the process was repeated three times more.[97] Finally, Hayes signed an appropriation without the rider, but Congress refused to pass another bill to fund federal marshals, who were vital to the enforcement of the Enforcement Acts.[97] The election laws remained in effect, but the funds to enforce them were curtailed.[97] Randall's role in the process was limited, but the Democrats' failure to force Hayes's acquiescence weakened his appeal as a potential presidential candidate in 1880.[98]

1880 presidential election

As the 1880 elections approached, Randall had two goals: to increase his control of the Pennsylvania Democratic Party, and to nominate Tilden for president.[99] His efforts at the former in 1875 had been successful, but Senator William Wallace's faction was again growing powerful.[100] If he wanted to hold the Speakership, as well as to wield influence in the next presidential canvass, Randall believed he must have a united state party behind him.[100] To that end, Randall spent much of his time outside of Congress travelling around his home state to line up support at the state convention in 1880.[101] Some of his allies' enthusiasm backfired against him, however, after McMullen and some supporters broke up an anti-Randall meeting in Philadelphia's 5th ward with such violence that one man was left dead.[102]

When the state convention gathered in April 1880, Randall was confident of victory, but soon found that the Wallace faction outnumbered his.[103] Wallace's majority scrambled the party's organization in Philadelphia and, although some Randall supporters received seats, the majority owed allegiance to the senator.[104] Despite the defeat, Randall pressed on for Tilden, both in Pennsylvania and elsewhere.[105] As rumors circulated that Tilden's health would keep him from running again, Randall remained a loyal Tilden man up to the national convention that June.[106] After the first ballot, the New York delegation released a letter from Tilden in which he withdrew from consideration.[107] Randall hoped for the ex-Tilden delegates to rally to him.[108] Many did so, and Randall surged to second place on the second ballot, but the momentum had shifted to another candidate, Major General Winfield Scott Hancock.[107] Nearly all the delegates shifted to Hancock, and he was nominated.[107]

Randall believed he had been betrayed by many he had thought would support him, but carried on regardless in support of his party's nominee.[109] Hancock (who remained on active duty) and the Republican nominee, James A. Garfield, did not campaign directly, in keeping with the customs of that time, but campaigns were conducted by other party members, including Randall.[110] Speaking in Pennsylvania and around the Midwest, Randall did his best to rally the people to Hancock against Garfield, but without success.[111] Garfield was elected with 214 electoral votes—including those of Pennsylvania.[112] Worse still for Randall, Garfield's victory had swept the Republicans back into a majority in the House, meaning Randall's time as Speaker was at an end.[112]

Later House service

Tariffs

When Randall returned to Washington in 1881 to begin his term in the 47th Congress, the legislature was controlled by Republicans.[lower-alpha 2][112] After Garfield's assassination later that year, Vice President Chester A. Arthur assumed the presidency. Arthur, like most Republicans, favored high tariffs, but he sought to simplify the tariff structure and to reduce excise taxes.[113] Randall, who had returned to his seat on the Appropriations Committee, favored the president's plan, and was among the few Democrats in the House to support it.[114] The bill that emerged from the Ways and Means Committee, dominated by protectionists, provided for only a 10 percent reduction.[113] After conference with the Senate, the resulting bill had an even smaller effect, reducing tariffs by an average of 1.47 percent.[115] It passed both houses narrowly on March 3, 1883, the last full day of the 47th Congress; Arthur signed the measure into law.[115] Toward the end, Randall took less part in the debate, feeling the tension between his supporters in the House, who wanted more reductions, and his constituents at home, who wanted less.[116]

The Democrats recaptured the House after the 1882 elections, but the incoming majority in the 48th Congress was divided on tariffs, with Randall's protectionist faction in the minority.[117] The new Democratic caucus was more Southern and Western than in previous Congresses, and contained many new members who were unfamiliar with Randall.[117] This led many to propose selecting a Speaker more in line with their own views, rather than returning Randall to the office.[118] Randall's attempt to canvass the incoming representatives was further hampered by an attack of the gout.[118] In the end, John G. Carlisle of Kentucky, an advocate of tariff reform, bested Randall in a poll of the Democratic caucus by a vote of 104 to 53.[118]

Carlisle selected William Ralls Morrison, another tariff reformer, to lead the Ways and Means committee, but allowed Randall to take charge of Appropriations.[119] Morrison's committee produced a bill proposing tariff reductions of 20%; Randall opposed the idea from the start, as did the Republicans.[119] Another bout of illness kept Randall away from Congress at a crucial time in April 1884, and the tariff bill passed a procedural hurdle by just two votes.[120] Two days later, Randall's Appropriations committee reported several funding bills with his support.[120] Many Democrats who had voted for Morrison's tariff were thereby reminded that Randall had the power to defeat spending that was important to them; when the final vote came, enough switched sides to join with Republicans in defeating the reform 156 to 151.[121]

1884 presidential election

As in 1880, the contest for the Democratic nomination for president in 1884 began under the shadow of Tilden.[122] Declining health forced Tilden's withdrawal by June 1884, and Randall felt free to pursue his own chance at the presidency.[123] He gathered some of the Pennsylvania delegates to his cause, but by the time the convention assembled in July, most of the former Tilden adherents had gathered around New York governor Grover Cleveland.[122] Early in the convention, Randall met with Daniel Manning, Cleveland's campaign manager, and soon thereafter Randall's delegates were instructed to cast their votes for Cleveland.[124] As his biographer, House, wrote, the "actual bargain struck between Randall and Manning is not known, but ... events would seem to show that Randall was promised control of federal patronage in Pennsylvania."[124][125]

Cleveland's campaign made extensive use of Randall, as he made speeches for Cleveland in New England, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Virginia, New York, and Connecticut, mainly in places where potential voters needed to be reassured that the Democrats did not want to lower the tariff so much that they would lose their jobs.[126] In a close election, Cleveland was elected over his Republican opponent, James G. Blaine.[127] Randall also took two tours of the South in 1884 after the election.[126] Although, he claimed the trips to be of a personal nature, they generated speculation that Randall was gathering support for another run at the Speakership in 1885.[126]

Resisting tariff reform

As the 49th Congress gathered in 1885, Cleveland's position on the tariff was still largely unknown. Randall declined to challenge Carlisle for Speaker, busying himself instead with the federal patronage in Pennsylvania and continued leadership of the Appropriations committee.[128] In February 1886, Morrison, still the chairman of Ways and Means, proposed a bill to decrease the surplus by buying and cancelling $10 million worth of federal bonds each month.[128] Cleveland opposed the plan, and Randall joined 13 Democrats and most Republicans in defeating it.[129] Later that year, however, Cleveland supported Morrison's attempt to reduce the tariff.[129] Again, Republicans and Randall's protectionist bloc combined to sink the measure.[129] In the lame-duck session of 1887, Randall attempted a compromise tariff that would eliminate duties on some raw materials while also dispensing with excises on tobacco and some liquors.[130] The bill attracted some support from Southern Democrats and Randall's protectionists, but Republicans and the rest of the Democratic caucus rejected it.[130]

Declining influence

The tariff fight continued into the 50th Congress, which opened in 1887, in which Democrats retained control of the House, with a reduced majority.[131] By that time, Cleveland had openly sided with the tariff reformers and backed the proposals introduced in 1888 by Representative Roger Q. Mills of Texas.[132] Mills had replaced Morrison at Ways and Means after the latter's defeat for reelection, and was as much in favor of tariff reform as the Illinoisan had been.[132] Mills's bill would make small cuts to tariffs on raw materials, but relatively deeper cuts to those on manufactured goods; Randall, representing a manufacturing district, opposed it immediately.[131] Randall was again ill and absent from the House when the Mills tariff passed by a 162 to 149 vote.[131] The Senate, now Republican-controlled, refused to consider the bill, and it died with the 50th Congress in 1889.[132]

Mills's and Cleveland's defeat on the tariff bill could be considered a victory for Randall, but the vote showed how isolated the former Speaker's protectionist ideas now made him in his party: only four Democrats voted against the tariff reductions.[133] The state party likewise turned against Randall and toward free trade, adopting a pro-tariff revision platform at the 1888 state Democratic convention.[134] At the same time, Randall seemingly reversed his long-standing commitment to fiscal economy by voting with the Republicans to override Cleveland's veto of the Dependent and Disability Pension Act.[135] The Act would have given a pension to every Union veteran (or their widows) who claimed he could no longer perform physical labor, regardless of whether his disability was war-related.[136] Cleveland's veto was in line with his record of small-government cost-cutting, with which Randall would normally have sympathized. Randall, perhaps in an effort to gain favor with veterans in his district, joined the Republicans in an unsuccessful attempt to override Cleveland's veto.[lower-alpha 3][138] Another possibility proposed by biographer House is that Randall saw the federal budget surplus as reason to cut tariffs; by increasing federal spending, he hoped to decrease the surplus and maintain the need for high tariffs.[138] Whatever the reason, the attempt failed and left Randall further alienated from his fellow Democrats.[138]

Death

Randall's positions on tariffs and pensions had made him, according to The New York Times, "a practical Republican" by 1888.[139] Voting with the opposing party so frequently was an effective tactic, as he faced only token Republican opposition for reelection that year.[140] Randall's health continued to decline. When the new congress began in 1889, he received special permission to be sworn into office from his bed, where he was confined.[140] The new Speaker, Republican Thomas Brackett Reed of Maine, appointed Randall to the Rules and Appropriations committees, but he had no impact during that term.[140]

On April 13, 1890, Randall died of colon cancer in his Washington home.[139] He had recently joined the First Presbyterian Church in the capital, and his funeral was held there.[141] He was buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.[141] Elected every two years from 1862 to 1888, Randall was the only prominent Democrat continuously on the national scene between those years.[142] In an obituary, the Bulletin of the American Iron and Steel Association described the congressman who had consistently protected their industry: "Not a great scholar, nor a great orator, nor a great writer, Samuel J. Randall was nevertheless a man of sterling common sense, quick perceptions, great courage, broad views and extraordinary capacity for work."[143] The only scholarly works on his life are a master's thesis by Sidney I. Pomerantz, written in 1932, and a doctoral dissertation by Albert V. House, from 1934; both are unpublished.[144] His papers were collected by the University of Pennsylvania library in the 1950s and he has been the subject of several journal articles (many by House), but awaits a full scholarly biography.[144][145]

See also

List of United States Congress members who died in office (1790–1899)

Notes

- ↑ The absent members were mostly Eastern members, involved in elections in their home states.[88]

- ↑ The Senate contained 37 Democrats, 37 Republicans, and two independents, one of whom caucused with each major party. Vice President Chester A. Arthur held the tie-breaking vote.[112]

- ↑ The bill passed in the next Congress and was signed into law by the Republican president Benjamin Harrison.[137]

References

- 1 2 Memorial 1891, pp. 6–7.

- 1 2 3 House 1934, p. 2.

- ↑ Scharf 1884, p. 595.

- ↑ Memorial 1891, pp. 6–7, 119.

- ↑ House 1934, pp. 4–5.

- 1 2 Memorial 1891, p. 120.

- 1 2 3 4 5 House 1934, p. 3.

- 1 2 Ward 1910, p. 348.

- ↑ Ward 1910, p. 245.

- ↑ Memorial 1891, p. 36.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 4.

- 1 2 House 1934, p. 5.

- 1 2 House 1934, pp. 6–7.

- 1 2 3 4 Memorial 1891, p. 121.

- 1 2 3 4 5 House 1934, pp. 8–9.

- 1 2 Memorial 1891, p. 122.

- ↑ Memorial 1891, p. 122; Dubin 1998, p. 195.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 10.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 12.

- ↑ Blaine 1886, p. 566.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 House 1935, p. 350.

- 1 2 3 House 1934, pp. 13–14.

- 1 2 3 4 Memorial 1891, p. 123.

- ↑ Foley 2013, p. 484.

- 1 2 House 1934, p. 16.

- ↑ House 1940, pp. 51–52.

- 1 2 House 1940, p. 54.

- ↑ House 1940, p. 55.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 19.

- 1 2 House 1934, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 4 House 1934, p. 24.

- 1 2 House 1934, p. 22.

- ↑ Trefousse 1989, p. 315.

- 1 2 House 1934, pp. 47–49.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 25.

- 1 2 3 4 House 1934, p. 29.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 30.

- 1 2 House 1934, p. 31.

- ↑ Memorial 1891, pp. 30, 69.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 32.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 33.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 222.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 35.

- 1 2 3 House 1934, p. 36.

- ↑ House 1934, pp. 38–39.

- 1 2 3 House 1934, pp. 40–42.

- ↑ House 1934, pp. 42–43.

- 1 2 Alston et al. 2006, p. 674.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 45.

- ↑ Alston et al. 2006, p. 689.

- ↑ Alston et al. 2006, p. 674; McPherson 1874, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 Memorial 1891, p. 125.

- 1 2 Wyatt-Brown 1965, p. 763.

- ↑ Wyatt-Brown 1965, p. 769.

- 1 2 3 4 Wyatt-Brown 1965, p. 771.

- ↑ Wyatt-Brown 1965, p. 774.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 58.

- ↑ House 1965, pp. 255–256.

- ↑ House 1965, pp. 262–268.

- ↑ House 1934, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ House 1934, pp. 68–70.

- ↑ House 1956, p. 251.

- ↑ House 1956, p. 252.

- ↑ House 1956, pp. 256–260.

- ↑ House 1956, pp. 260–265.

- 1 2 House 1965, pp. 269–270.

- 1 2 House 1934, pp. 84–89.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 92.

- ↑ House 1934, pp. 90–91.

- 1 2 Robinson 2001, pp. 126–127, 141.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 93.

- 1 2 Robinson 2001, pp. 145–154.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 95.

- ↑ Robinson 2001, p. 158.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 96.

- ↑ Robinson 2001, pp. 159–161.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 97.

- ↑ Robinson 2001, pp. 166–171.

- ↑ Foley 2013, p. 491.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 103.

- ↑ Robinson 2001, pp. 182–184.

- ↑ Robinson 2001, pp. 185–189.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 109.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 124.

- ↑ House 1934, pp. 48, 125.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 125.

- 1 2 Hoogenboom 1995, p. 356.

- 1 2 House 1934, pp. 125–126.

- 1 2 3 Hoogenboom 1995, pp. 358–359.

- 1 2 House 1934, p. 127.

- ↑ Guenther 1983, pp. 283–284.

- ↑ House 1934, pp. 129–130.

- ↑ Hoogenboom 1995, p. 366.

- 1 2 Guenther 1983, pp. 289–291.

- ↑ Hoogenboom 1995, p. 367.

- 1 2 3 4 5 House 1934, pp. 114–115.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hoogenboom 1995, pp. 392–402.

- ↑ House 1934, pp. 131–132.

- ↑ House 1934, pp. 176–177.

- 1 2 House 1934, p. 161.

- ↑ House 1934, pp. 165–174.

- ↑ House 1934, pp. 174–175.

- ↑ House 1934, pp. 182–184.

- ↑ House 1934, pp. 184–185.

- ↑ House 1934, pp. 185–187.

- ↑ House 1960, pp. 201–203.

- 1 2 3 Clancy 1958, pp. 139–140.

- ↑ House 1960, pp. 210–211.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 191.

- ↑ Ackerman 2003, pp. 164–165, 202.

- ↑ House 1934, pp. 192–193.

- 1 2 3 4 Ackerman 2003, p. 221.

- 1 2 Reeves 1975, pp. 330–333.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 227.

- 1 2 Reeves 1975, pp. 334–335.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 232.

- 1 2 House 1934, p. 235.

- 1 2 3 House 1934, p. 236.

- 1 2 House 1934, pp. 237–238.

- 1 2 House 1934, pp. 239–240.

- ↑ House 1934, pp. 240–241.

- 1 2 Welch 1988, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 242.

- 1 2 House 1934, p. 244.

- ↑ Welch 1988, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 House 1934, p. 245.

- ↑ Welch 1988, pp. 40–41.

- 1 2 House 1934, p. 249.

- 1 2 3 House 1934, p. 250.

- 1 2 House 1934, p. 252.

- 1 2 3 House 1934, p. 253.

- 1 2 3 Welch 1988, pp. 87–89.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 254.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 281.

- ↑ House 1934, p. 219.

- ↑ Welch 1988, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Welch 1988, p. 101.

- 1 2 3 House 1934, p. 220.

- 1 2 New York Times 1890.

- 1 2 3 House 1934, p. 282.

- 1 2 House 1934, p. 283.

- ↑ Adams 1954, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Bulletin 1890, p. 108.

- 1 2 Foley 2013, pp. 481–482.

- ↑ Adams 1954, p. 45.

Sources

Books

- Memorial Addresses on the Life and Character of Samuel J. Randall, a Representative from Pennsylvania, Delivered in the House of Representatives and in the Senate, Fifty-First Congress, First Session. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1891. OCLC 568611.

- Ackerman, Kenneth D. (2003). Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of President James A. Garfield. New York, New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-1151-5.

- Blaine, James G. (1886). Twenty Years of Congress. Vol. 2. Norwich, Connecticut: The Henry Bill Publishing Company. OCLC 4560136.

- Clancy, Herbert J. (1958). The Presidential Election of 1880. Chicago, Illinois: Loyola University Press. ISBN 978-1-258-19190-0.

- Dubin, Michael J. (1998). United States Congressional elections, 1788–1997 : the official results of the elections of the 1st through 105th Congresses. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0-7864-0283-0.

- Hoogenboom, Ari (1995). Rutherford Hayes: Warrior and President. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0641-2.

- House, Albert V. (1935). "Samuel Jackson Randall". Dictionary of American Biography. Vol. XV. New York, New York: C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 350–351. OCLC 4171403.

- McPherson, Edward (1874). A Hand-book of Politics for 1874. Washington, D.C.: Solomons & Chapman. OCLC 17723145.

- Reeves, Thomas C. (1975). Gentleman Boss: The Life of Chester A. Arthur. New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-46095-6.

- Robinson, Lloyd (2001) [1968]. The Stolen Election: Hayes versus Tilden—1876. New York: Tom Doherty Associates. ISBN 978-0-7653-0206-9.

- Scharf, John Thomas (1884). History of Philadelphia. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: L.H. Evarts & Co. ISBN 9781404758285. OCLC 1851563.

- Trefousse, Hans L. (1989). Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York, New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-31742-0.

- Ward, George Kemp (1910). Andrew Warde and His Descendants, 1597–1910. New York, New York: A.T. De La Mare Printing and Publishing. OCLC 13957563.

- Welch, Richard E. (1988). The Presidencies of Grover Cleveland. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0355-7.

Articles

- Adams, Thomas R. (January 1954). "The Samuel J. Randall Papers". Pennsylvania History. 21 (1): 45–54. JSTOR 27769474.

- Alston, Lee J.; Jenkins, Jeffery A.; Nonnenmacher, Tomas (September 2006). "Who Should Govern Congress? Access to Power and the Salary Grab of 1873" (PDF). The Journal of Economic History. 66 (3): 674–706. doi:10.1017/s0022050706000295. JSTOR 3874856. S2CID 14919997.

- Foley, Edward B. (2013). "Virtue over Party: Samuel Randall's Electoral Heroism and Its Continuing Importance" (PDF). UC Irvine Law Review. 3 (3): 475–509. OCLC 713316046.

- Guenther, Karen (January 1983). "Potter Committee Investigation of the Disputed Election of 1876". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 61 (3): 281–295. JSTOR 30149125.

- House, Albert V. (February 1940). "Northern Congressional Democrats as Defenders of the South During Reconstruction". The Journal of Southern History. 6 (1): 46–71. doi:10.2307/2191938. JSTOR 2191938.

- House, Albert V. (April 1956). "Men, Morals, and Manipulation in the Pennsylvania Democracy of 1875". Pennsylvania History. 23 (2): 248–266. JSTOR 27769647.

- House, Albert V. (April 1960). "Internal Conflicts in Key States in the Democratic Convention of 1880". Pennsylvania History. 27 (2): 188–216. JSTOR 27769951.

- House, Albert V. (September 1965). "The Speakership Contest of 1875: Democratic Response to Power". The Journal of American History. 52 (2): 252–274. doi:10.2307/1908807. JSTOR 1908807.

- Wyatt-Brown, Bertram (December 1965). "The Civil Rights Act of 1875". The Western Political Quarterly. 18 (4): 763–775. doi:10.1177/106591296501800403. JSTOR 445883. S2CID 154418104.

Dissertation

- House, Albert V. (1934). The Political Career of Samuel Jackson Randall (Ph.D.). University of Wisconsin. OCLC 51818085.

Newspapers

- "Samuel J. Randall". The Bulletin. Vol. 24. The American Iron and Steel Association. April 16, 1890. p. 108.

- "Samuel J. Randall Dead" (PDF). The New York Times. April 14, 1890.

Further reading

- Detailed election results at electoral history of Samuel J. Randall

- The Samuel J. Randall Papers, including correspondence, congressional papers and other printed materials, are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

External links

- United States Congress. "Samuel J. Randall (id: R000039)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

New York Tribune (April 14, 1890) Obituary for Samuel J Randall,