| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /vaɪˈɡæbətrɪn/ vy-GAB-ə-trin |

| Trade names | Sabril, Vigadrone |

| Other names | γ-Vinyl-GABA |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a610016 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80–90% |

| Protein binding | 0% |

| Metabolism | not metabolized |

| Elimination half-life | 5–8 hours in young adults, 12–13 hours in the elderly. |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.165.122 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

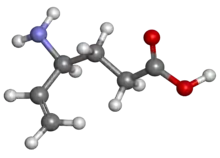

| Formula | C6H11NO2 |

| Molar mass | 129.159 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 171 to 177 °C (340 to 351 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Vigabatrin, sold under the brand name Sabril, is a medication used to treat epilepsy. It became available as a generic medication in 2019.[2]

It works by inhibiting the breakdown of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). It is also known as γ-vinyl-GABA, and is a structural analogue of GABA, but does not bind to GABA receptors.[3]

Medical uses

Epilepsy

In Canada, vigabatrin is approved for use as an adjunctive treatment (with other drugs) in treatment resistant epilepsy, complex partial seizures, secondary generalized seizures, and for monotherapy use in infantile spasms in West syndrome.[3]

As of 2003, vigabatrin is approved in Mexico for the treatment of epilepsy that is not satisfactorily controlled by conventional therapy (adjunctive or monotherapy) or in recently diagnosed patients who have not tried other agents (monotherapy).[4]

Vigabatrin is also indicated for monotherapy use in secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures, partial seizures, and in infantile spasms due to West syndrome.[4]

On August 21, 2009, Lundbeck announced that the US Food and Drug Administration had granted two New Drug Application approvals for vigabatrin. The drug is indicated as monotherapy for pediatric patients one month to two years of age with infantile spasms for whom the potential benefits outweigh the potential risk of vision loss, and as adjunctive (add-on) therapy for adult patients with refractory complex partial seizures (CPS) who have inadequately responded to several alternative treatments and for whom the potential benefits outweigh the risk of vision loss.[5]

In 1994, Feucht and Brantner-Inthaler reported that vigabatrin reduced seizures by 50-100% in 85% of children with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome who had poor results with sodium valproate.[6]

Others

Vigabatrin reduced cholecystokinin tetrapeptide-induced symptoms of panic disorder, in addition to elevated cortisol and ACTH levels, in healthy volunteers.[7]

Vigabatrin is also used to treat seizures in succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency (SSADHD), which is an inborn GABA metabolism defect that causes intellectual disability, hypotonia, seizures, speech disturbance, and ataxia through the accumulation of γ-Hydroxybutyric acid (GHB). Vigabatrin helps lower GHB levels through GABA transaminase inhibition. However, this is in the brain only; it has no effect on peripheral GABA transaminase, so the GHB keeps building up and eventually reaches the brain.[8]

Adverse effects

Central nervous system

Sleepiness (12.5%), headache (3.8%), dizziness (3.8%), nervousness (2.7%), depression (2.5%), memory disturbances (2.3%), diplopia (2.2%), aggression (2.0%), ataxia (1.9%), vertigo (1.9%), hyperactivity (1.8%), vision loss (1.6%) (See below), confusion (1.4%), insomnia (1.3%), impaired concentration (1.2%), personality issues (1.1%).[3] Out of 299 children, 33 (11%) became hyperactive.[3]

Some patients develop psychosis during the course of vigabatrin therapy,[9] which is more common in adults than in children.[10] This can happen even in patients with no prior history of psychosis.[11] Other rare CNS side effects include anxiety, emotional lability, irritability, tremor, abnormal gait, and speech disorder.[3]

Gastrointestinal

Abdominal pain (1.6%), constipation (1.4%), vomiting (1.4%), and nausea (1.4%). Dyspepsia and increased appetite occurred in less than 1% of subjects in clinical trials.[3]

Body as a whole

Teratogenicity

A teratology study conducted in rabbits found that a dose of 150 mg/kg/day caused cleft palate in 2% of pups and a dose of 200 mg/kg/day caused it in 9%.[3] This may be due to a decrease in methionine levels, according to a study published in March 2001.[12] In 2005, a study conducted at the University of Catania was published stating that rats whose mothers had consumed 250–1000 mg/kg/day had poorer performance in the water maze and open-field tasks, rats in the 750 mg group were underweight at birth and did not catch up to the control group, and rats in the 1000 mg group did not survive pregnancy.[13]

There is no controlled teratology data in humans to date.

Sensory

In 2003, vigabatrin was shown by Frisén and Malmgren to cause irreversible diffuse atrophy of the retinal nerve fiber layer in a retrospective study of 25 patients.[14] This has the most effect on the outer area (as opposed to the macular, or central area) of the retina.[15] Visual field defects had been reported as early as 1997 by Tom Eke and others, in the UK. Some authors, including Comaish et al. believe that visual field loss and electrophysiological changes may be demonstrable in up to 50% of Vigabatrin users.

The retinal toxicity of vigabatrin can be attributed to a taurine depletion.[16]

Due to safety issues, the Vigabatrin REMS Program is required by the FDA to ensure informed decisions before initiating and to ensure appropriate use of this drug.[17]

Interactions

A study published in 2002 found that vigabatrin causes a statistically significant increase in plasma clearance of carbamazepine.[18]

In 1984, Drs Rimmer and Richens at the University of Wales reported that administering vigabatrin with phenytoin lowered the serum phenytoin concentration in patients with treatment-resistant epilepsy.[19] Five years later, the same two scientists reported a fall in concentration of phenytoin of 23% within five weeks in a paper describing their failed attempt at elucidating the mechanism behind this interaction.[20]

Pharmacology

Vigabatrin is an irreversible mechanism-based inhibitor of gamma-aminobutyric acid aminotransferase (GABA-AT), the enzyme responsible for the catabolism of GABA. Inhibition of GABA-AT results in increased levels of GABA in the brain.[3][21] Vigabatrin is a racemic compound, and its [S]-enantiomer is pharmacologically active.[22],[23]

Pharmacokinetics

With most drugs, elimination half-life is a useful predictor of dosing schedules and the time needed to reach steady state concentrations. In the case of vigabatrin, however, it has been found that the half-life of biologic activity is far longer than the elimination half-life.[25]

For vigabatrin, there is no range of target concentrations because researchers found no difference between the serum concentration levels of responders and those of non-responders.[26] Instead, the duration of action is believed to be more a function of the GABA-T resynthesis rate; levels of GABA-T do not usually return to their normal state until six days after stopping the medication.[23]

History

Vigabatrin was developed in the 1980s with the specific goal of increasing GABA concentrations in the brain in order to stop an epileptic seizure. To do this, the drug was designed to irreversibly inhibit the GABA transaminase, which degrades the GABA substrate. Although the drug was approved for treatment in the United Kingdom in 1989, the authorized use of Vigabatrin by US Food and Drug Administration was delayed twice in the United States before 2009. It was delayed in 1983 because animal trials produced intramyelinic edema, however, the effects were not apparent in human trials so the drug design continued. In 1997, the trials were temporarily suspended because it was linked to peripheral visual field defects in humans.[27]

Society and culture

Brand Names

Vigabatrin is sold as Sabril in Canada,[28] Mexico,[4] and the United Kingdom.[29] The brand name in Denmark is Sabrilex. Sabril was approved in the United States on August 21, 2009, and is marketed in the U.S. by Lundbeck Inc., which acquired Ovation Pharmaceuticals, the U.S. sponsor in March 2009.

Generic equivalents

On January 16, 2019, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first generic version of Sabril (vigabatrin) in the United States.[30]

Research

Though vigabatrin has been used to treat seizures in infants, as of 2023, its effectiveness in this age group has been evaluated in only one study. Due to the lack of a comparison group, the evidence is inconclusive.[31]

References

- ↑ Anvisa (March 31, 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published April 4, 2023). Archived from the original on August 3, 2023. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- ↑ "FDA approves first generic version of Sabril to help treat seizures in adults and pediatric patients with epilepsy". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Long PW (2003). "Vigabatrin". Drug Monograph. Internet Mental Health. Archived from the original on April 23, 2006.

- 1 2 3 "DEF Mexico: Sabril". Diccionario de Especialdades Farmaceuticas. (49 ed.). 2003. Archived from the original on September 14, 2005.

- ↑ Bresnahan R, Gianatsi M, Maguire MJ, Tudur Smith C, Marson AG (July 2020). "Vigabatrin add-on therapy for drug-resistant focal epilepsy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (7): CD007302. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007302.pub3. PMC 8211760. PMID 32730657.

- ↑ Feucht M, Brantner-Inthaler S (1994). "Gamma-vinyl-GABA (vigabatrin) in the therapy of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: an open study". Epilepsia. 35 (5): 993–8. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb02544.x. PMID 7925171. S2CID 24204172.

- ↑ Zwanzger P, Baghai TC, Schuele C, Strohle A, Padberg F, Kathmann N, Schwarz M, Moller HJ, Rupprecht R (2001). "Vigabatrin decreases cholecystokinin-tetrapeptide (CCK-4) induced panic in healthy volunteers". Neuropsychopharmacology. 25 (5): 699–703. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00266-4. PMID 11682253.

- ↑ Pearl PL, Wiwattanadittakul N, Roullet JB, Gibson KM (May 5, 2004). "Succinic Semialdehyde Dehydrogenase Deficiency". In dam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJ, Gripp KW, Amemiya A (eds.). GeneReviews. University of Washington. PMID 20301374. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ↑ Sander JW, Hart YM (1990). "Vigabatrin and behaviour disturbance". Lancet. 335 (8680): 57. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(90)90190-G. PMID 1967367. S2CID 34456538.

- ↑ Chiaretti A, Castorina M, Tortorolo L, Piastra M, Polidori G (1994). "[Acute psychosis and vigabatrin in childhood]". La Pediatria Medica e Chirurgica: Medical and Surgical Pediatrics (in Italian). 16 (5): 489–90. PMID 7885961.

- ↑ Sander JW, Hart YM, Trimble MR, Shorvon SD (1991). "Vigabatrin and psychosis". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 54 (5): 435–9. doi:10.1136/jnnp.54.5.435. PMC 488544. PMID 1865207.

- ↑ Abdulrazzaq YM, Padmanabhan R, Bastaki SM, Ibrahim A, Bener A (2001). "Placental transfer of vigabatrin (gamma-vinyl GABA) and its effect on concentration of amino acids in the embryo of TO mice". Teratology. 63 (3): 127–33. doi:10.1002/tera.1023. PMID 11283969.

- ↑ Lombardo SA, Leanza G, Meli C, Lombardo ME, Mazzone L, Vincenti I, Cioni M (2005). "Maternal exposure to the antiepileptic drug vigabatrin affects postnatal development in the rat" (PDF). Neurological Sciences. 26 (2): 89–94. doi:10.1007/s10072-005-0441-6. hdl:2108/194069. PMID 15995825. S2CID 25257244. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ↑ Frisén L, Malmgren K (2003). "Characterization of vigabatrin-associated optic atrophy". Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 81 (5): 466–73. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0420.2003.00125.x. PMID 14510793.

- ↑ Buncic JR, Westall CA, Panton CM, Munn JR, MacKeen LD, Logan WJ (2004). "Characteristic retinal atrophy with secondary "inverse" optic atrophy identifies vigabatrin toxicity in children". Ophthalmology. 111 (10): 1935–42. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.03.036. PMC 3880364. PMID 15465561.

- ↑ Gaucher D, Arnault E, Husson Z, Froger N, Dubus E, Gondouin P, et al. (November 2012). "Taurine deficiency damages retinal neurones: cone photoreceptors and retinal ganglion cells". Amino Acids. 43 (5): 1979–1993. doi:10.1007/s00726-012-1273-3. PMC 3472058. PMID 22476345.

- ↑ "SABRIL® (vigabatrin) tablets, for oral use SABRIL® (vigabatrin) powder for oral..." Sabril.net. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ↑ Sánchez-Alcaraz A, Quintana MB, López E, Rodríguez I, Llopis P (December 2002). "Effect of vigabatrin on the pharmacokinetics of carbamazepine". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 27 (6): 427–430. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00441.x. PMID 12472982. S2CID 29986581.

- ↑ Rimmer EM, Richens A (1984). "Double-blind study of gamma-vinyl GABA in patients with refractory epilepsy". Lancet. 1 (8370): 189–90. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(84)92112-3. PMID 6141335. S2CID 54336689.

- ↑ Rimmer EM, Richens A (1989). "Interaction between vigabatrin and phenytoin". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 27 (Suppl 1): 27S–33S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb03458.x. PMC 1379676. PMID 2757906.

- ↑ Rogawski MA, Löscher W (July 2004). "The neurobiology of antiepileptic drugs". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 5 (7): 553–564. doi:10.1038/nrn1430. PMID 15208697. S2CID 2201038. Archived from the original on December 16, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ↑ Sheean G, Schramm T, Anderson DS, Eadie MJ (1992). "Vigabatrin--plasma enantiomer concentrations and clinical effects". Clinical and Experimental Neurology. 29: 107–116. PMID 1343855.

- 1 2 Gram L, Larsson OM, Johnsen A, Schousboe A (1989). "Experimental studies of the influence of vigabatrin on the GABA system". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 27 (Suppl 1): 13S–17S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb03455.x. PMC 1379673. PMID 2757904.

- ↑ Storici P, De Biase D, Bossa F, Bruno S, Mozzarelli A, Peneff C, et al. (January 2004). "Structures of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) aminotransferase, a pyridoxal 5'-phosphate, and [2Fe-2S] cluster-containing enzyme, complexed with gamma-ethynyl-GABA and with the antiepilepsy drug vigabatrin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (1): 363–373. doi:10.1074/jbc.M305884200. PMID 14534310.

- ↑ Browne TR (November 1998). "Pharmacokinetics of antiepileptic drugs". Neurology. 51 (5 Suppl 4): S2–S7. doi:10.1212/wnl.51.5_suppl_4.s2. PMID 9818917. S2CID 39231047.

- ↑ Lindberger M, Luhr O, Johannessen SI, Larsson S, Tomson T (2003). "Serum concentrations and effects of gabapentin and vigabatrin: observations from a dose titration study". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 25 (4): 457–62. doi:10.1097/00007691-200308000-00007. PMID 12883229. S2CID 35834401.

- ↑ Ben-Menachem E (2011). "Mechanism of action of vigabatrin: correcting misperceptions". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 124 (192): 5–15. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2011.01596.x. PMID 22061176. S2CID 25347559.

- ↑ "Vigabatrin Drug Information". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Treatments for Epilepsy - Vigabatrin". Norfolk and Waveney Mental Health Partnership NHS Trust. Archived from the original on February 11, 2002. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- ↑ "FDA approves first generic version of Sabril to help treat seizures in adults and pediatric patients with epilepsy". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (Press release). September 11, 2019.

- ↑ Treadwell JR, Wu M, Tsou AY (October 25, 2022). Management of Infantile Epilepsies (Report). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). doi:10.23970/ahrqepccer252. PMID 36383706. Report No.: 22(23)-EHC004R eport No.: 2021-SR-01.