| SVT-40 | |

|---|---|

SVT-40 from the Swedish Army Museum, Stockholm | |

| Type | Semi-automatic rifle |

| Place of origin | Soviet Union |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1938-present (SVT-38) 1940–present (SVT-40) |

| Used by | See Users |

| Wars | |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Fedor Tokarev |

| Designed | 1938 (updated 1940)[1] |

| Produced | 1938–1945[2] |

| No. built | SVT-38: 150,000[3] SVT-40: 1,600,000[4][5] |

| Variants | SVT-38, SVT-40 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 3.85 kilograms (8.5 lb) unloaded[1] |

| Length | 1,226 millimetres (48.3 in)[1] |

| Barrel length | 625 millimetres (24.6 in)[1] |

| Cartridge | 7.62×54mmR[1] |

| Caliber | 7.62 mm |

| Action | Gas-operated short-stroke piston, tilting bolt[1] |

| Muzzle velocity | 830–840 m/s (2,720–2,760 ft/s)[6] (light bullet arr. 1908) |

| Effective firing range | 500 metres (550 yd), 1,000 metres (1,100 yd)+ (with scope) |

| Feed system | 10-round detachable box magazine[1] |

The SVT-40 (Samozaryadnaya Vintovka Tokareva, Obrazets 1940 goda, "Tokarev self-loading rifle, model of 1940", Russian: Самозарядная винтовка Токарева, образец 1940 года, often nicknamed "Sveta") is a Soviet semi-automatic battle rifle that saw widespread service during and after World War II. It was intended to be the new service rifle of the Soviet Red Army, but its production was disrupted by the German invasion in 1941, resulting in a change back to the Mosin–Nagant rifle for the duration of World War II. After the war, the Soviet Union adopted new rifles, such as the SKS and the AK-47.

History

In the early 1930s, the Soviet Union requested the development of a semi-automatic rifle to replace the Mosin-Nagant, taking inspiration from the Mexican Mondragón rifle. The design was left up to two individuals, Sergei Simonov and Fedor Tokarev.[7] Simonov, who had experience in developing the Fedorov Avtomat, created a prototype for the AVS-36 in 1931. The rifle was used during the Winter War but was removed from service in 1941 due to design flaws.[7]

SVT-38

In 1938, Tokarev's rifle was accepted for production, under the designation SVT-38 with hopes that it would become the new standard issue rifle of the Red Army. Ambitious production plans anticipated two million rifles per year by 1942. Production began at Tula Arsenal in July 1939 (production at Izhmash began in late 1939).[8]

The SVT-38 is a gas-operated rifle with a short-stroke, spring-loaded piston above the barrel and a tilting bolt,[1] a system that would later be used in the FN FAL.[9] The SVT-38 was equipped with a bayonet and a 10-round detachable magazine. The receiver was open-top, which enabled reloading of the magazine using five-round Mosin–Nagant stripper clips.[9] The sniper variant had an additional locking notch for a see-through scope mount and was equipped with a 3.5×21 PU telescopic sight.[9]

The SVT-38 saw its combat debut in the 1939–1940 Winter War with Finland. The rifle had many design flaws, as its gas port was prone to fouling, the magazine would sometimes fall out during use, and it was inaccurate, only being effective up to 600m.[9] Production of the SVT-38 was terminated in April 1940 after some 150,000 examples had been manufactured.

SVT-40

With the removal of the SVT-38 from service, an improved design, the SVT-40, entered production. It was a more refined, lighter design incorporating a folding magazine release and lightening cuts. The hand guard was now of one-piece construction and the cleaning rod was housed under the barrel. Other changes were made to simplify manufacturing. Production of the improved version began in July 1940 at Tula and later at factories in Izhevsk and Podolsk. Production of the Mosin–Nagant M1891/30 bolt-action rifle continued, and it remained the standard-issue rifle to Red Army troops, with the SVT-40 more often issued to non-commissioned officers and elite units like the naval infantry. Since these factories already had experience manufacturing the SVT-38, output increased quickly and an estimated 70,000 SVT-40s were produced in 1940.

By the time of Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the USSR in June 1941, the SVT-40 was already in widespread use by the Red Army. In a Soviet infantry division's table of organization and equipment, one-third of rifles were supposed to be SVTs, though in practice they seldom achieved this ratio. The first months of the war were disastrous for the Soviet Union; they lost hundreds of thousands of SVT-40s. To make up for this, the production of the Mosin–Nagant rifles was reintroduced. In contrast, the SVT was more difficult to manufacture, and troops with only rudimentary training had difficulty maintaining it. Submachine guns like the PPSh-41 had proven their value as simple, cheap, and effective weapons to supplement infantry firepower. This led to a gradual decline in SVT production. In 1941, over one million SVTs were produced but in 1942 Izhevsk arsenal was ordered to cease SVT production and switch back to the Mosin–Nagant 91/30. Only 264,000 SVTs were manufactured in 1942 and production continued to diminish until the order to cease production was finally given in January 1945. Total production of the SVT-38/40 was around 1,600,000 rifles, of which 51,710 were the SVT-40 sniper variant.[1][4][5]

SVTs frequently suffered from vertical shot dispersion; the army reported that the rifles were of "flimsy construction and there were difficulties experienced in their repair and maintenance".[10] The stock, made of Arctic Birch, was prone to cracking in the wrist from recoil. This was generally remedied by drilling and inserting one or two large industrial bolts horizontally into the stock just before the wrist meets the receiver. Many rifles were also poorly seated in their stocks, letting the receiver shift on firing. This led to a field modification that selectively shimmed the stock with birch chips, usually around the receiver and in between where the wood stock meets the lower metal handguard. For a sniper rifle, this was unacceptable and production of the specialized sniper variant of the SVT was terminated in 1942.[1] Milling scope rails in the receivers of standard SVT rifles was also discontinued. Other production changes included a new, simpler muzzle brake design with two vents per-side instead of the six on the original.

AVT-40 automatic rifle

To supplement the Red Army's shortage of machine guns, an SVT version capable of full-automatic fire (designated the AVT-40) was ordered into production on 20 May 1942; the first batches reached the troops in July.[11] It was externally similar to the SVT, but its modified safety also acted as a fire selector allowing for both semi-automatic and fully automatic fire modes. When fired automatically the rifle had a rate of fire of approximately 750 RPM, faster than even the DP machine gun which fired the same cartridge at 550 RPM. To better resist the stress of automatic fire, the AVT featured a slightly stouter stock made of hardwood usually distinguished with a large “A” engraved in it; surplus AVT stocks were later used on refurbished SVTs. In service, the AVT proved a disappointment: the automatic fire was largely uncontrollable, and the rifles often suffered breakages under the increased strain. Documents discovered after the war indicated that during testing, under continuous Full Auto fire, an AVT-40's barrel would be "shot out", meaning the rifling in the barrel would be completely worn down, in as little as 200-250 rounds. The use of the AVT's automatic fire mode was subsequently prohibited, and production of the rifle was relatively brief; none were made after the summer of 1943.[11]

SKT-40

A shorter carbine version SKT-40 (СКТ-40) was designed in 1940 and was submitted to a competitive test with a design of Simonov in the same year; neither was accepted for service.[12] Later, a prototype version chambered for the new, shorter, 7.62×39mm round was developed, but was not accepted for production.[11] An assault rifle based on a scaled-down SVT with 7.62x41mm chambering called the AT-44 was also put into development, competing with the AS-44 design. It failed to be accepted for similar reliability issues as the AVT.[13] A silenced variation was also experimented with, though it too ended in failure.[14][15]

SVTs outside of the Soviet Union

The first country outside the Soviet Union to employ the SVT was Finland, which captured some 2,700 SVT-38s during the Winter War, and over 15,000 SVTs during the Continuation War. The SVT saw extensive use in Finnish hands.[16] The Finns even attempted to make their own clone of the SVT-38 designated Tapako, though only a prototype was ever conceived.[17] The Finns would continue to experiment with producing their own SVT based rifles until the late 1950s with the introduction of the RK-62.

Germany captured hundreds of thousands of SVTs from the Eastern Front. As the Germans were short of self-loading rifles themselves, SVT-38 and 40s, designated respectively as Selbstladegewehr 258(r) and Selbstladegewehr 259(r) by the Wehrmacht, saw widespread use in German hands against their former owners. The study of the SVT's gas-operated action also aided in the development of the German Gewehr 43 rifle.[18]

During the 1940s, Switzerland began looking into equipping its military with semi-auto rifles. Although never officially adopted, W+F Bern produced an almost faithful clone of the SVT with 7.5 mm Swiss chambering and a 6-round magazine called the AK44.[19]

Italy also produced at least one prototype loosely copying an SVT, which is extant in Beretta's collection, but its designation or exact details are unknown.[20]

Post-war

.jpg.webp)

After the war, SVTs were mostly withdrawn from service and refurbished in arsenals, then stored. In Soviet service, firearms like the SKS and the AK-47 as well as the later SVD made the SVT obsolete, and the rifle was generally out of service by 1955. Only a few SVTs were exported to Soviet allies and clients. The Korean People's Army reportedly received some before the Korean War.[21][22] The Finnish Army retired the SVT in 1958, and about 7,500 rifles were sold to the United States civilian market through firearm importer Interarms. This marked the end of SVTs in regular service.

In the Soviet Union, some SVTs (without bayonets) were sold as civilian hunting rifles,[23] although other SVTs were kept in storage until the 1990s, when many rifles were sold abroad, along with other surplus military firearms.

Users

.jpg.webp)

.svg.png.webp) Croatia[24]

Croatia[24] Czechoslovakia: 1st Czechoslovak Independent Brigade in the USSR[25]

Czechoslovakia: 1st Czechoslovak Independent Brigade in the USSR[25] Estonian partisans during and after World War 2[26]

Estonian partisans during and after World War 2[26] Finland: Captured from Soviet troops, AVT-40 version also used.[17] Finnish captured SVT-38s, 40s and AVT-40s have a [SA] property stamp.

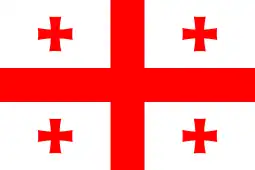

Finland: Captured from Soviet troops, AVT-40 version also used.[17] Finnish captured SVT-38s, 40s and AVT-40s have a [SA] property stamp. Georgia[27]

Georgia[27] Italian Partisans: Used examples captured from German soldiers[28]

Italian Partisans: Used examples captured from German soldiers[28] Lithuania: Lithuanian civil Police used captured SVT-40s during the German occupation.[29]

Lithuania: Lithuanian civil Police used captured SVT-40s during the German occupation.[29] Luhansk People's Republic: Donated by Russia and used by the Luhansk People's Militia[30]

Luhansk People's Republic: Donated by Russia and used by the Luhansk People's Militia[30].svg.png.webp) Nazi Germany: Captured from Soviet troops, designated as Selbstladegewehr 259(r)[31]

Nazi Germany: Captured from Soviet troops, designated as Selbstladegewehr 259(r)[31] Poland: Polish Armed Forces in the East[32]

Poland: Polish Armed Forces in the East[32] Russia:Limited numbers of SVT-40s issued to militias in Luhansk.[30]

Russia:Limited numbers of SVT-40s issued to militias in Luhansk.[30] Soviet Union

Soviet Union North Korea

North Korea Vietnam

Vietnam East Germany

East Germany Ukraine: On November 23, 2005, the government signed an agreement with the NATO Logistics and Supply Agency to begin the destruction of excess stockpiles of weapons and ammunition in exchange for material and financial assistance. As of August 6, 2008, the Ministry of Defense had 11,500 SVT rifles in storage (10,000 serviceable and 1,500 destined for disposal);[33] as of August 15, 2011, 1000 units remained in the storage of the Ministry of Defense,[34] On February 29, 2012, a decision was approved to dispose of 180 rifles. [35] Seen modified with suppressor and scope during the 2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine[36]

Ukraine: On November 23, 2005, the government signed an agreement with the NATO Logistics and Supply Agency to begin the destruction of excess stockpiles of weapons and ammunition in exchange for material and financial assistance. As of August 6, 2008, the Ministry of Defense had 11,500 SVT rifles in storage (10,000 serviceable and 1,500 destined for disposal);[33] as of August 15, 2011, 1000 units remained in the storage of the Ministry of Defense,[34] On February 29, 2012, a decision was approved to dispose of 180 rifles. [35] Seen modified with suppressor and scope during the 2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine[36] Ukrainian Insurgent Army: SVT-38 and SVT-40 captured from Germans and Soviets.[37]

Ukrainian Insurgent Army: SVT-38 and SVT-40 captured from Germans and Soviets.[37]

Museum exhibits

- One SVT-38 rifle, one SVT-40 rifle and one SKT-40 carbine are in the collection of Tula State Arms Museum in Tula Kremlin[38]

- Three SVT-40 rifles and one SKT-40 carbine are on display at the J.M. Davis Arms & Historical Museum in Claremore, Oklahoma

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Modern Firearms article on SVT-40 Archived 16 December 2003 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ https://www.m9130.info/svt-40

- ↑ Suciu, Peter (13 January 2021). "Ranked: Which World War II Semi-Automatic Weapon Was the Best?". National Interest.

- 1 2 Steve Kehaya; Joe Poyer (1996). The SKS Carabine (CKC45g) (4th ed.). North Cape Publications, Inc. p. 10. ISBN 1-882391-14-4.

- 1 2 Edward Clinton Ezell (1983). Small Arms of the World: A Basic Manual of Small Arms (12th ed.). Stackpole Books. p. 894. ISBN 0-8117-1687-2.

- ↑

- May 1946 (U.S.) Intelligence Bulletin on Tokarev M1940 gives 2720 ft/s

- Семен Федосеев, "Самозарядная винтовка Токарева", Техника и вооружение, June 2005, p. 16, gives 840 m/s

- 1 2 Pegler, Martin (2019). Sniping Rifles on the Eastern Front 1939-1945. Osprey Publishing. p. 28.

- ↑ "The Red Army's Self Loading Rifles: A Brief History Of The Tokarev Rifles Models of 1938 and 1940. By Vic Thomas Of Michigan Historical Collectables". Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Pegler, Martin (2019). Sniping Rifles on the Eastern Front 1939-45. Osprey Publishing. p. 29.

- ↑ Small Arms of the World by W. H. B. Smith 9th Edition Revised by Joseph E. Smith 1969 p. 583

- 1 2 3 Bolotin, David Naumovich (1995). Walter, John; Pohjolainen], Heikki (eds.). Soviet Small-arms and Ammunition. trans. Igor F. Naftul'eff. Hyvinkää: Finnish Arms Museum Foundation (Suomen asemuseosäätiö). p. 111. ISBN 9519718419.

- ↑ Bolotin, David Naumovich (1995). Walter, John; Pohjolainen], Heikki (eds.). Soviet Small-arms and Ammunition. trans. Igor F. Naftul'eff. Hyvinkää: Finnish Arms Museum Foundation (Suomen asemuseosäätiö). p. 112. ISBN 9519718419.

- ↑ Опытный автомат Токарева АТ-44 (СССР. 1944 год)

- ↑ Развитие глушителей звука выстрела, устройство глушителя винтовки СВТ-40, карабина Маузер-98К и пистолета-пулемета Ингрэм

- ↑ В продолжение данной темы публикуем материал об

- ↑ Jowett, Philip; Snodgrass, Brent (5 July 2006). Finland at War 1939–45. Elite 141. Osprey Publishing. p. 48. ISBN 9781841769691.

- 1 2 "Rifles, part 4". 15 January 2017. Archived from the original on 23 May 2023.

- ↑ Bishop, Chris, ed. (1998). "Tokarev rifles". The encyclopedia of weapons of World War II. Barnes & Noble. pp. 218–219. ISBN 9780760710227.

- ↑ RIA: Prototype W+F Bern AK44 Copy of the SVT

- ↑ McCollum, Ian (15 July 2016). "Pavesi Prototype SVT Copy (Video)". Forgotten Weapons. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ↑ "North Korean Small Arms (Democratic People's Republic of Korea)". Small Arms Review. Vol. 16, no. 2. June 2012.

- ↑ Edwards, Paul M. (2006). "Communist weapons, infantry". Korean War Almanac. Facts On File. pp. 498-499. ISBN 0-8160-6037-1.

- ↑ М. Блюм, А. Волнов. Охотнику о СВТ // журнал "Охота и охотничье хозяйство", № 11, 1989

- ↑ Vladimir Brnardic (22 November 2016). World War II Croatian Legionaries: Croatian Troops Under Axis Command 1941—45. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-4728-1767-9.

- ↑ Gelbič, Michal. "1st Czechoslovak Independent Brigade". czechpatriots.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ↑ Nigel, Thomas; Caballero Jurado, Carlos (25 January 2002). Germany's Eastern Front Allies (2): Baltic Forces. Men-at-Arms 363. Osprey Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 9781841761930.

- ↑ Small Arms Survey (1998). Politics From The Barrel of a Gun (PDF). Cambridge University Press. p. 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 January 2011.

- ↑ Gianluigi, Usai; Riccio, Ralph (28 January 2017). Italian partisan weapons in WWII. Schiffer Military History. p. 167. ISBN 978-0764352102.

- ↑ Nigel & Caballero Jurado 2002, p. 46.

- 1 2 "A very interesting video showing a range of obsolescent small arms including a Polish PPS-43, a PPSh, an M1 Thompson, an SKS, SVT-40, an RPK and a Mosin-Nagant". Twitter. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ↑ W. Darrin Weaver (2005). Desperate Measures: The Last-Ditch Weapons of the Nazi Volkssturm. Collector Grade Publications. p. 61. ISBN 0889353727.

- ↑ McNab, Chris (2002). 20th Century Military Uniforms (2nd ed.). Kent: Grange Books. p. 191. ISBN 1-84013-476-3.

- ↑ "Про затвердження переліку військового майна Збройних ... | від 06.08.2008 № 1092-р (Сторінка 1 з 27)". 4 March 2016. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ↑ "Перелік військового майна Збр... | від 15.08.2011 № 1022-р". 25 January 2022. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ↑ "Про утилізацію стрілецької зброї | від 29.02.2012 № 108-р". 19 November 2021. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ↑ "Peep the suppressed SVT-40 battle rifle". Twitter. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ↑ "SVT-40 Tokarev semi-auto rifle". m9130.info. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ↑ "Кроме переданных в музей Ф. В. Токаревым опытных образцов и поступивших с военных складов штатных самозарядных винтовок образца 1938 г. и 1940 г. в коллекции есть оружие, имеющее мемориальное значение. ... Самозарядный карабин Токарева СКТ-40, редкий на сегодняшний день образец, был личным оружием В. Г. Жаворонкова, секретаря Тульского областного комитета ВКП (б), председателя городского комитета обороны Тулы осенью 1941 г."

Оружие боевое автоматическое / официальный сайт Тульского государственного музея оружия

External links

- History and technicalities of the SVT-40

- SVT-40 Pictorial

- СВТ трудная судьба, Kalashnikov magazine, 2001/6, pp. 50–56