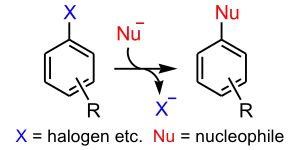

A nucleophilic aromatic substitution is a substitution reaction in organic chemistry in which the nucleophile displaces a good leaving group, such as a halide, on an aromatic ring. Aromatic rings are usually nucleophilic, but some aromatic compounds do undergo nucleophilic substitution. Just as normally nucleophilic alkenes can be made to undergo conjugate substitution if they carry electron-withdrawing substituents, so normally nucleophilic aromatic rings also become electrophilic if they have the right substituents.

This reaction differs from a common SN2 reaction, because it happens at a trigonal carbon atom (sp2 hybridization). The mechanism of SN2 reaction does not occur due to steric hindrance of the benzene ring. In order to attack the C atom, the nucleophile must approach in line with the C-LG (leaving group) bond from the back, where the benzene ring lies. It follows the general rule for which SN2 reactions occur only at a tetrahedral carbon atom.

The SN1 mechanism is possible but very unfavourable unless the leaving group is an exceptionally good one. It would involve the unaided loss of the leaving group and the formation of an aryl cation. In the SN1 reactions all the cations employed as intermediates were planar with an empty p orbital. This cation is planar but the p orbital is full (it is part of the aromatic ring) and the empty orbital is an sp2 orbital outside the ring.[1]

Nucleophilic aromatic substitution mechanisms

Aromatic rings undergo nucleophilic substitution by several pathways.

- SNAr (addition-elimination) mechanism

- aromatic SN1 mechanism encountered with diazonium salts

- benzyne mechanism (E1cB-AdN)

- free radical SRN1 mechanism

- ANRORC mechanism

- Vicarious nucleophilic substitution

The SNAr mechanism is the most important of these. Electron withdrawing groups activate the ring towards nucleophilic attack. For example if there are nitro functional groups positioned ortho or para to the halide leaving group, the SNAr mechanism is favored.

SNAr reaction mechanism

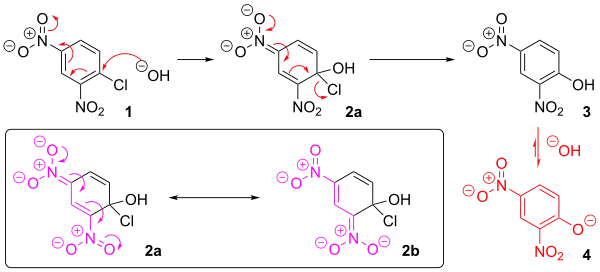

The following is the reaction mechanism of a nucleophilic aromatic substitution of 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene (1) in a basic solution in water.

Since the nitro group is an activator toward nucleophilic substitution, and a meta director, it is able to stabilize the additional electron density (via resonance) when the aromatic compound is attacked by the hydroxide nucleophile. The resulting intermediate, named the Meisenheimer complex (2a), the ipso carbon is temporarily bonded to the hydroxyl group. This Meisenheimer complex is extra stabilized by the additional electron-withdrawing nitro group (2b).

In order to return to a lower energy state, either the hydroxyl group leaves, or the chloride leaves. In solution, both processes happen. A small percentage of the intermediate loses the chloride to become the product (2,4-dinitrophenol, 3), while the rest return to the reactant (1). Since 2,4-dinitrophenol is in a lower energy state, it will not return to form the reactant, so after some time has passed, the reaction reaches chemical equilibrium that favors the 2,4-dinitrophenol, which is then deprotonated by the basic solution (4).

The formation of the resonance-stabilized Meisenheimer complex is slow because the loss of aromaticity due to nucleophilic attack results in a higher-energy state. By the same coin, the loss of the chloride or hydroxide is fast, because the ring regains aromaticity. Recent work indicates that, sometimes, the Meisenheimer complex is not always a true intermediate but may be the transition state of a 'frontside SN2' process, particularly if stabilization by electron-withdrawing groups is not very strong.[2] A 2019 review argues that such 'concerted SNAr' reactions are more prevalent than previously assumed.[3]

Aryl halides cannot undergo the classic 'backside' SN2 reaction. The carbon-halogen bond is in the plane of the ring because the carbon atom has a trigonal planar geometry. Backside attack is blocked and this reaction is therefore not possible.[4] An SN1 reaction is possible but very unfavourable. It would involve the unaided loss of the leaving group and the formation of an aryl cation.[4] The nitro group is the most commonly encountered activating group, other groups are the cyano and the acyl group.[5] The leaving group can be a halogen or a sulfide. With increasing electronegativity the reaction rate for nucleophilic attack increases.[5] This is because the rate-determining step for an SNAr reaction is attack of the nucleophile and the subsequent breaking of the aromatic system; the faster process is the favourable reforming of the aromatic system after loss of the leaving group. As such, the following pattern is seen with regard to halogen leaving group ability for SNAr: F > Cl ≈ Br > I (i.e. an inverted order to that expected for an SN2 reaction). If looked at from the point of view of an SN2 reaction this would seem counterintuitive, since the C-F bond is amongst the strongest in organic chemistry, when indeed the fluoride is the ideal leaving group for an SNAr due to the extreme polarity of the C-F bond. Nucleophiles can be amines, alkoxides, sulfides and stabilized carbanions.[5]

Nucleophilic aromatic substitution reactions

Some typical substitution reactions on arenes are listed below.

- In the Bamberger rearrangement N-phenylhydroxylamines rearrange to 4-aminophenols. The nucleophile is water.

- In the Sandmeyer reaction diazonium salts react with halides.

- The Smiles rearrangement is the intramolecular version of this reaction type.

Nucleophilic aromatic substitution is not limited to arenes, however; the reaction takes place even more readily with heteroarenes. Pyridines are especially reactive when substituted in the aromatic ortho position or aromatic para position because then the negative charge is effectively delocalized at the nitrogen position. One classic reaction is the Chichibabin reaction (Aleksei Chichibabin, 1914) in which pyridine is reacted with an alkali-metal amide such as sodium amide to form 2-aminopyridine.[6]

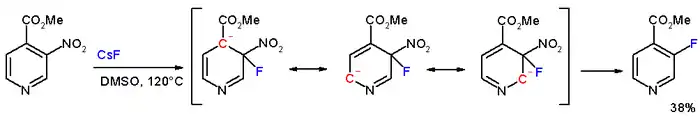

In the compound methyl 3-nitropyridine-4-carboxylate, the meta nitro group is actually displaced by fluorine with cesium fluoride in DMSO at 120 °C.[7]

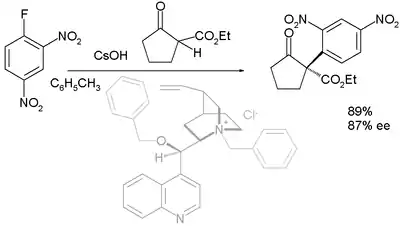

Asymmetric nucleophilic aromatic substitution

With carbon nucleophiles such as 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds the reaction has been demonstrated as a method for the asymmetric synthesis of chiral molecules.[8] First reported in 2005, the organocatalyst (in a dual role with that of a phase transfer catalyst) is derived from cinchonidine (benzylated at N and O).

See also

References

- ↑ Clayden, Jonathan; Greeves, Nick; Warren, Stuart (2012-03-15). Organic Chemistry (Second ed.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 514–515. ISBN 978-0-19-927029-3.

- ↑ Neumann CN, Hooker JM, Ritter T (June 2016). "Concerted nucleophilic aromatic substitution with (19)F(-) and (18)F(-)". Nature. 534 (7607): 369–73. doi:10.1038/nature17667. PMC 4911285. PMID 27281221.

- ↑ Rohrbach S, Smith AJ, Pang JH, Poole DL, Tuttle T, Chiba S, Murphy JA (November 2019). "Concerted Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution Reactions". Angewandte Chemie. 58 (46): 16368–16388. doi:10.1002/anie.201902216. PMC 6899550. PMID 30990931.

- 1 2 Clayden J. Organic Chemistry. Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 3 Goldstein SW, Bill A, Dhuguru J, Ghoneim O (September 2017). "Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution Addition and Identification of an Amine". Journal of Chemical Education. 94 (9): 1388–90. Bibcode:2017JChEd..94.1388G. doi:10.1021/acs.jchemed.6b00680.

- ↑ March J (1966). Advanced Organic Chemistry, Reactions, Mechanisms and Structure (3rd ed.). ISBN 0-471-85472-7.

- ↑ Tjosaas F, Fiksdahl A (February 2006). "A simple synthetic route to methyl 3-fluoropyridine-4-carboxylate by nucleophilic aromatic substitution". Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 11 (2): 130–3. doi:10.3390/11020130. PMC 6148553. PMID 17962783.

- ↑ Bella M, Kobbelgaard S, Jørgensen KA (March 2005). "Organocatalytic regio- and asymmetric C-selective S(N)Ar reactions-stereoselective synthesis of optically active spiro-pyrrolidone-3,3'-oxoindoles". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (11): 3670–1. doi:10.1021/ja050200g. PMID 15771481.