Lakeshore | |

|---|---|

| Municipality of Lakeshore | |

Lakeshore Municipal Office | |

Flag  Seal | |

Lakeshore  Lakeshore | |

| Coordinates: 42°15′N 82°41′W / 42.250°N 82.683°W | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| County | Essex |

| Formed | 1999 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Tracey Bailey |

| • MP | Chris Lewis (CPC) |

| • MPP | Anthony Leardi (PC) |

| Area | |

| • Land | 530.33 km2 (204.76 sq mi) |

| Population (2021)[2] | |

| • Total | 40,410 |

| • Density | 69.0/km2 (179/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Website | www.lakeshore.ca |

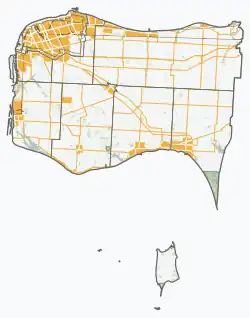

Lakeshore is a municipality on Lake St. Clair, in Essex County, Ontario, Canada. It was incorporated in 1999 by amalgamating the Town of Belle River with the townships of Maidstone, Rochester, Tilbury North, and Tilbury West. It is the largest and the most populous municipality within Essex County. However, it is part of the Windsor census metropolitan area.

Lakeshore has a significant concentration of French Canadians and is one of only four communities in Southern Ontario (excluding Eastern Ontario) in which more than 5% (the provincial average) of the population is francophone. The others are Welland, Pain Court, and Penetanguishene. In the 2011 census, 7.7% of the population reported French as their mother tongue, and 17.2% reported knowledge of both official languages.[3] Lakeshore also has a historic black community, along the Puce River, made up of descendants of refugee slaves from the South in the United States who immigrated to Canada for freedom, using the Underground Railroad network.[4]

Communities

The Municipality of Lakeshore comprises the communities of Belle River, Comber, Deerbrook, Elmstead, Emeryville, Haycroft, Lighthouse Cove, North Woodslee, Pike Creek, Pleasant Park, Puce, Ruscom Station, South Woodslee, St. Joachim, Stoney Point, and Strangfield, as well as the far eastern section of Tecumseh.

A small portion of the township's easternmost area is considered by some to be part of Tilbury, although Tilbury proper is located in the neighbouring municipality of Chatham-Kent.

Geography

Although incorporated as a town, the vast majority of Lakeshore is rural, being made up of cleared farmland predominantly used for the cultivation of cash crops such as soybeans and winter wheat. The Comber Wind Farm is also located here.

As in the rest of Essex County and Chatham-Kent, the terrain is extremely flat and regular. The terrain slopes very gently from the southern border of Lakeshore on Highway 8, with an average elevation of 188 m (617 ft), to the shore of Lake St. Clair at 176 m (577 ft). The highest land is in the southwestern corner of the town, near the town of Essex, at an elevation of 193 m (633 ft).[5]

The area is drained by a series of slow-moving rivers and creeks, all of which flow northward into Lake St. Clair: from west to east, these are Pike Creek, the Puce River, Belle River, the Ruscom River, and finally Big Creek and Baptiste Creek, which form the northeastern border of Lakeshore at their junction with the Thames River.

The major transportation arteries through Lakeshore, including Highway 401, the Tecumseh Road, and County Roads 22, 42 and 46, all follow an east–west parallel toward Windsor and Detroit in the west and toward Chatham-Kent in the east. The only significant exception is Highway 77, which connects Leamington to Highway 401 via Staples.

History

Areas along Lake St. Clair and the Puce, Belle, and Ruscom rivers were originally occupied by the Huron and Wyandot First Nations. Some French colonists associated with Fort Detroit and the fur trade settled in this area in the 18th century. Their descendants are known as Fort Detroit French. They also came from Sandwich, where colonists had developed farms at what was known as Petite Côte, a bend in the Detroit River.

The coast of Lake St. Clair and lots fronting the Puce, Belle, and Ruscom rivers were first surveyed in 1793 by Patrick McKniff. The area was not fully divided into concessions and lots, however, until the rear lines of the townships and the Middle Road (today County Road 46) were surveyed by Mahlon Burwell in 1823. Land speculation was endemic in Essex County at that time, as in many other parts of Upper Canada. Much of the present town of Lakeshore was once owned by a single speculator, the fur trader John Askin: by 1797, he held 80 lots, concentrated primarily along the Pêche (Pike) Puce, Belle, and Ruscom rivers.[6]

From the 1840s, the town received numerous Irish immigrants, fleeing the Great Famine. Later additional waves of French Canadians migrated from Quebec. Development was slow until the construction of a series of railroads through the area. These include the Great Western Railway, opened in 1854 and passing through Belle River, and the Canada Southern Railway (later owned by New York Central and Michigan Central), opened in 1872 and passing through Comber. These stimulated the settlement by new migrants from the East.[7]

Following the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act that abolished slavery in most of the British Empire, the Lakeshore region became one of several end points of the Underground Railroad, an informal network running from the South of the United States to help refugee slaves gain freedom. In 1851, the Refugee Home Society was founded in Detroit by Michigan and Ontario abolitionists. Under the direction of Henry Walton Bibb, the society purchased scattered lots in and around Maidstone, Puce, and Belle River to resettle refugee blacks. Although Michigan was a free state, slavecatchers operated in Detroit to capture refugees for the high bounties offered under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.[8]

The two oldest communities in Lakeshore are Comber and Belle River. Samuel Taylor II, who developed and owned half the land west of main street, had part of his land laid out into village lots. This includes property that was donated to build two schools and two churches. It is due to his many contributions in the area that Taylor Avenue in Comber still exists today.[9] Other landowners, including John Gracey and William MacDowell, two Scotch-Irish Presbyterians from Comber, Ireland followed suit. It was named after their home town in 1848 or 1850 when it was erected as a Police village.[10][11]

Belle River, named for the river where it developed, was incorporated as a village on November 26, 1874, but its origins can be traced to the Jesuit Mission of St. Jude. The mission was founded in 1834 to serve the religious needs of the local population of French Catholics. The mission did not receive a resident pastor until 1857, after the Great Western Railway opened the area to large-scale immigration. Over the course of the 1870s, the town's population was tripled by an influx of settlers from the province of Quebec, sometimes referred to as Canadian French, in contrast to the Fort Detroit French.[12] The earliest industries in the town were operated by Luc and Denis Ouellette, who established a sawmill and gristmill on opposite sides of the river.[13]

In 1881, the population of Comber was 250 and that of Belle River was 650.[14]

Stoney Point (French: Pointe-aux-Roches) was settled by 1851 and incorporated as a village in 1881, at which time it had a population of 375.[15] The church of St. Joachim, which became the centre of the village of the same name, was completed in 1882 and enlarged in 1891. It was established to serve the needs of French Catholics in the area along the Ruscom River, who were distant from the existing parishes in Belle River and Stoney Point.[11][16]

Belle River was well known for bootlegging during Prohibition in the United States. The Wellington hotel, once located on Notre Dame, the town's main street, exported alcohol to the United States. Owners and residents of many American-owned cottages on Charron Beach Road also participated in bootlegging liquor.

In the 1920s, James Scott Cooper, a well-known local entrepreneur and bootlegger, built mansions from his profits in Walkerville and Belle River. The Cooper Court Motel and Bar in Belle River, built in 1920, still operates today. Cooper was a philanthropist and contributed greatly to the construction of Belle River's first high school in 1922, St. James High School; it was named informally to honour Cooper's generosity. The building still stands today, housing the local Canadian Legion on Notre Dame Street.[17]

Demographics

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Lakeshore had a population of 40,410 living in 14,386 of its 14,954 total private dwellings, a change of 10.4% from its 2016 population of 36,611. With a land area of 529 km2 (204 sq mi), it had a population density of 76.4/km2 (197.8/sq mi) in 2021.[18][1]

Economy

Lakeshore's economy is based primarily on agriculture and manufacturing. Over 27% of the workforce is employed in the manufacturing sector. The prominence of manufacturing is an outgrowth of the town's proximity to Windsor and Detroit, the historic centre of North American automobile production. The economy of Lakeshore remains closely tied to that of Windsor: more than 50% of the town's total workforce is employed in Windsor.[19]

In recent years, important developments in renewable energy, particularly in wind power, have taken place in the town. It is the site of the 72-turbine Comber Wind Farm.

Sports

The community's hockey team is the two-time defending Stobbs Division Champions Lakeshore Canadiens, who play in the Provincial Junior Hockey League.

The youth sports teams are Belle River Jr. Canadiens (Hockey), Lakeshore Lightning (Girls Hockey), Belle River Braves (Baseball) and Belle River F.C. (Soccer).

Belle River is the birthplace of retired NHL player Tie Domi, and NHL player Aaron Ekblad was raised in Belle River.

Since 1989, Belle River has been known as the "Jet Ski Capital of Canada" due to the numerous personal watercraft riders and racers in the town, many of whom are American visitors. In the past, the community's racing team was named after the URL: www.belleriverbia.com. To this day there continues to be an annual event hosted by The CAN AM Watercross Tour in honour of the sport in conjunction with the town's annual Sunsplash Festival.

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Thames River Lighthouse in Lighthouse Cove

Thames River Lighthouse in Lighthouse Cove St. Joachim

St. Joachim Church in South Woodslee

Church in South Woodslee South Woodslee Cemetery

South Woodslee Cemetery

See also

References

- 1 2 "Lakeshore census profile". 2016 Census of Population. Statistics Canada. February 8, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Lakeshore census profile". 2021 Census of Population. Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- ↑ Statistics Canada (February 8, 2012). "Census Subdivision of Lakeshore". Focus on Geography Series. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ↑ Brown, Alan L. "Puce River Black Community". Ontario's Historical Plaques. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ↑ "The Atlas of Canada - Toporama". Natural Resources Canada. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ↑ Clark, John. Land Power and Economics on the Frontier of Upper Canada. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press. pp. 66, 73, 631 note 156. See 339 for map of Askin's land.

- ↑ History of Belle River, 1874-1974 (Histoire de Belle Rivière, 1874-1974). Tecumseh, Ont.: Tribune Print. and Pub. Co., 1974. pp. 7–9.

- ↑ O’Farrell, John K. A. "Bibb, Henry Walton". Dictionary of Canadian biography. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ↑ Mika, Nick and Helma (1977). Places In Ontario. Belleville, Ontario: Mika Publishing Company. p. 473. ISBN 0-919303-14-5.

- ↑ Duquette, Scott R.; Griffin, Debbie J.; Hornick, Victoria; Gardiner, Maxine. The Tilbury Story: Celebration of a Century 1887-1987. Tilbury Ont.: Corporation of the Town of Tilbury. p. 13.

- 1 2 Map of "Tilbury West Township, Essex County 1880"

- ↑ Jack D. Cécillon, Prayers, Petitions, and Protests: The Catholic Church and the Ontario Schools Crisis in the Windsor Border Region, 1910-1928, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2013, pp. 16-41

- ↑ History of Belle River, 1874-1974 (Histoire de Belle Rivière, 1874-1974). Tecumseh, Ont.: Tribune Print. and Pub. Co., 1974. pp. 12, 9, 49.

- ↑ Illustrated Historical Atlas of the Counties of Essex and Kent. Toronto: H. Belden and Co. 1880–1881. pp. 11, 14.

- ↑ Brown, Alan L. "The Founding of Stoney Point". Ontario's Historical Plaques. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ↑ Stewart, Peter. "Heritage Assessment of St. Joachim Church, its Rectory, and Monument". Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ↑ Gervais, Marty. "James Scott Cooper". The Walkerville Times 33.

- ↑ "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, census divisions and census subdivisions (municipalities), Ontario". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ↑ "2009 Community Profile: Town of Lakeshore" (PDF). Windsor Essex Development Commission. Retrieved February 8, 2014.