| |

| Formation | 28 November 1660 |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | London, SW1 United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°30′22″N 00°07′56″W / 51.50611°N 0.13222°W |

Membership |

|

| Charles III | |

President | Sir Adrian Smith |

Foreign Secretary | Sir Robin William Grimes |

Treasurer | Sir Andrew Hopper |

Main organ | Council |

Staff | ~225 |

| Website | royalsociety |

| Remarks | Motto: Nullius in verba ("Take nobody's word for it") |

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge,[1] is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, recognising excellence in science, supporting outstanding science, providing scientific advice for policy, education and public engagement and fostering international and global co-operation. Founded on 28 November 1660, it was granted a royal charter by King Charles II as The Royal Society and is the oldest continuously existing scientific academy in the world.[2]

The society is governed by its Council, which is chaired by the society's president, according to a set of statutes and standing orders. The members of Council and the president are elected from and by its Fellows, the basic members of the society, who are themselves elected by existing Fellows. As of 2020, there are about 1,700 fellows, allowed to use the postnominal title FRS (Fellow of the Royal Society), with up to 73 new fellows appointed each year from a pool of around 800 candidates.[3] There are also royal fellows, honorary fellows and foreign members. Up to 24 new foreign members are appointed each year (from the same pool of 800) and they are allowed to use the postnominal title ForMemRS (Foreign Member of the Royal Society). The Royal Society president is Adrian Smith, who took up the post and started his five-year term on 30 November 2020,[3] replacing the previous president, Venki Ramakrishnan.

Since 1967, the society has been based at 6–9 Carlton House Terrace, a Grade I listed building in central London which was previously used by the Embassy of Germany, London.

History

Founding and early years

The Invisible College has been described as a precursor group to the Royal Society of London, consisting of a number of natural philosophers around Robert Boyle. The concept of "invisible college" is mentioned in German Rosicrucian pamphlets in the early 17th century. Ben Jonson in England referenced the idea, related in meaning to Francis Bacon's House of Solomon, in a masque The Fortunate Isles and Their Union from 1624/5.[4] The term accrued currency in the exchanges of correspondence within the Republic of Letters.[5]

In letters dated 1646 and 1647, Boyle refers to "our invisible college" or "our philosophical college". The society's common theme was to acquire knowledge through experimental investigation.[6] Three dated letters are the basic documentary evidence: Boyle sent them to Isaac Marcombes (Boyle's former tutor and a Huguenot, who was then in Geneva), Francis Tallents who at that point was a fellow of Magdalene College, Cambridge,[7] and London-based Samuel Hartlib.[8]

The Royal Society started from groups of physicians and natural philosophers, meeting at a variety of locations, including Gresham College in London. They were influenced by the "new science", as promoted by Francis Bacon in his New Atlantis, from approximately 1645 onwards.[9] A group known as "Philosophical Society of Oxford" was run under a set of rules still retained by the Bodleian Library.[10] After the English Restoration, there were regular meetings at Gresham College.[11] It is widely held that these groups were the inspiration for the foundation of the Royal Society.[10]

Another view of the founding, held at the time, was that it was due to the influence of French scientists and the Montmor Academy in 1657, reports of which were sent back to England by English scientists attending. This view was held by Jean-Baptiste du Hamel, Giovanni Domenico Cassini, Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle and Melchisédech Thévenot at the time and has some grounding in that Henry Oldenburg, the society's first secretary, had attended the Montmor Academy meeting.[12] Robert Hooke, however, disputed this, writing that:

[Cassini] makes, then, Mr Oldenburg to have been the instrument, who inspired the English with a desire to imitate the French, in having Philosophical Clubs, or Meetings; and that this was the occasion of founding the Royal Society, and making the French the first. I will not say, that Mr Oldenburg did rather inspire the French to follow the English, or, at least, did help them, and hinder us. But 'tis well known who were the principal men that began and promoted that design, both in this city and in Oxford; and that a long while before Mr Oldenburg came into England. And not only these Philosophic Meetings were before Mr Oldenburg came from Paris; but the Society itself was begun before he came hither; and those who then knew Mr Oldenburg, understood well enough how little he himself knew of philosophic matter.[13]

On 28 November 1660, which is considered the official foundation date of the Royal Society, a meeting at Gresham College of 12 natural philosophers decided to commence a "Colledge for the Promoting of Physico-Mathematicall Experimentall Learning". Amongst those founders were Christopher Wren, Robert Boyle, John Wilkins, William Brouncker and Robert Moray.[14]

At the second meeting, Sir Robert Moray announced that the King approved of the gatherings, and a royal charter was signed on 15 July 1662 which created the "Royal Society of London", with Lord Brouncker serving as the first president. A second royal charter was signed on 23 April 1663, with the king noted as the founder and with the name of "the Royal Society of London for the Improvement of Natural Knowledge"; Robert Hooke was appointed as Curator of Experiments in November. This initial royal favour has continued and, since then, every monarch has been the patron of the society.[15]

The society's early meetings included experiments performed first by Hooke and then by Denis Papin, who was appointed in 1684. These experiments varied in their subject area, and were both important in some cases and trivial in others.[16] The society also published an English translation of Essays of Natural Experiments Made in the Accademia del Cimento, under the Protection of the Most Serene Prince Leopold of Tuscany in 1684, an Italian book documenting experiments at the Accademia del Cimento.[17] Although meeting at Gresham College, the society temporarily moved to Arundel House in 1666 after the Great Fire of London, which did not harm Gresham but did lead to its appropriation by the Lord Mayor. The society returned to Gresham in 1673.[18]

There had been an attempt in 1667 to establish a permanent "college" for the society. Michael Hunter argues that this was influenced by "Solomon's House" in Bacon's New Atlantis and, to a lesser extent, by J. V. Andreae's Christianopolis, dedicated research institutes, rather than the colleges at Oxford and Cambridge, since the founders only intended for the society to act as a location for research and discussion. The first proposal was given by John Evelyn to Robert Boyle in a letter dated 3 September 1659; he suggested a grander scheme, with apartments for members and a central research institute. Similar schemes were expounded by Bengt Skytte and later Abraham Cowley, who wrote in his Proposition for the Advancement of Experimental Philosophy in 1661 of a "'Philosophical College", with houses, a library and a chapel. The society's ideas were simpler and only included residences for a handful of staff, but Hunter maintains an influence from Cowley and Skytte's ideas.[19] Henry Oldenburg and Thomas Sprat put forward plans in 1667 and Oldenburg's co-secretary, John Wilkins, moved in a council meeting on 30 September 1667 to appoint a committee "for raising contributions among the members of the society, in order to build a college".[20] These plans were progressing by November 1667, but never came to anything, given the lack of contributions from members and the "unrealised—perhaps unrealistic"—aspirations of the society.[21]

18th century

During the 18th century, the gusto that had characterised the early years of the society faded; with a small number of scientific "greats" compared to other periods, little of note was done. In the second half, it became customary for His Majesty's Government to refer highly important scientific questions to the council of the society for advice, something that, despite the non-partisan nature of the society, spilled into politics in 1777 over lightning conductors. The pointed lightning conductor had been invented by Benjamin Franklin in 1749, while Benjamin Wilson invented blunted ones. During the argument that occurred when deciding which to use, opponents of Franklin's invention accused supporters of being American allies rather than being British, and the debate eventually led to the resignation of the society's president, Sir John Pringle. During the same time period, it became customary to appoint society fellows to serve on government committees where science was concerned, something that still continues.[22]

The 18th century featured remedies to many of the society's early problems. The number of fellows had increased from 110 to approximately 300 by 1739, the reputation of the society had increased under the presidency of Sir Isaac Newton from 1703 until his death in 1727,[23] and editions of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society were appearing regularly.[24] During his time as president, Newton arguably abused his authority; in a dispute between himself and Gottfried Leibniz over the invention of infinitesimal calculus, he used his position to appoint an "impartial" committee to decide it, eventually publishing a report written by himself in the committee's name.[23] In 1705, the society was informed that it could no longer rent Gresham College and began a search for new premises. After unsuccessfully applying to Queen Anne for new premises, and asking the trustees of Cotton House if they could meet there, the council bought two houses in Crane Court, Fleet Street, on 26 October 1710.[25] This included offices, accommodation and a collection of curiosities. Although the overall fellowship contained few noted scientists, most of the council were highly regarded, and included at various times John Hadley, William Jones and Hans Sloane.[26] Because of the laxness of fellows in paying their subscriptions, the society ran into financial difficulty during this time; by 1740, the society had a deficit of £240. This continued into 1741, at which point the treasurer began dealing harshly with fellows who had not paid.[27] The business of the society at this time continued to include the demonstration of experiments and the reading of formal and important scientific papers, along with the demonstration of new scientific devices and queries about scientific matters from both Britain and Europe.[28]

Some modern research has asserted that the claims of the society's degradation during the 18th century are false. Richard Sorrenson writes that "far from having 'fared ingloriously', the society experienced a period of significant productivity and growth throughout the eighteenth century", pointing out that many of the sources critical accounts are based on are in fact written by those with an agenda.[29] While Charles Babbage wrote that the practice of pure mathematics in Britain was weak, laying the blame at the doorstep of the society, the practice of mixed mathematics was strong and although there were not many eminent members of the society, some did contribute vast amounts – James Bradley, for example, established the nutation of the Earth's axis with 20 years of detailed, meticulous astronomy.[30]

Politically within the society, the mid-18th century featured a "Whig supremacy" as the so-called "Hardwicke Circle" of Whig-leaning scientists held the society's main Offices. Named after Lord Hardwicke, the group's members included Daniel Wray and Thomas Birch and was most prominent in the 1750s and '60s. The circle had Birch elected secretary and, following the resignation of Martin Folkes, the circle helped oversee a smooth transition to the presidency of Earl Macclesfield, whom Hardwicke helped elect.[31] Under Macclesfield, the circle reached its "zenith", with members such as Lord Willoughby and Birch serving as vice-president and secretary respectively. The circle also influenced goings-on in other learned societies, such as the Society of Antiquaries of London. After Macclesfield's retirement, the circle had Lord Morton elected in 1764 and Sir John Pringle elected in 1772.[32] By this point, the previous Whig "majority" had been reduced to a "faction", with Birch and Willoughby no longer involved, and the circle declined in the same time frame as the political party did in British politics under George III, falling apart in the 1780s.[33]

In 1780, the society moved again, this time to Somerset House. The property was offered to the society by His Majesty's Government and, as soon as Sir Joseph Banks became president in November 1778, he began planning the move. Somerset House, while larger than Crane Court, was not satisfying to the fellows; the room to store the library was too small, the accommodation was insufficient and there was not enough room to store the museum at all. As a result, the museum was handed to the British Museum in 1781 and the library was extended to two rooms, one of which was used for council meetings.[34]

19th century

The early 19th century has been seen as a time of decline for the society; of 662 fellows in 1830, only 104 had contributed to the Philosophical Transactions. The same year, Charles Babbage published Reflections on the Decline of Science in England, and on Some of Its Causes, which was deeply critical of the society. The scientific Fellows of the society were spurred into action by this, and eventually James South established a Charters Committee "with a view to obtaining a supplementary Charter from the Crown", aimed primarily at looking at ways to restrict membership. The Committee recommended that the election of Fellows take place on one day every year, that the Fellows be selected on consideration of their scientific achievements and that the number of fellows elected a year be limited to 15. This limit was increased to 17 in 1930 and 20 in 1937;[22] it is currently 52.[3] This had a number of effects on the society: first, the society's membership became almost entirely scientific, with few political Fellows or patrons. Second, the number of Fellows was significantly reduced—between 1700 and 1850, the number of Fellows rose from approximately 100 to approximately 750. From then until 1941, the total number of Fellows was always between 400 and 500.[35]

The period did lead to some reform of internal Society statutes, such as in 1823 and 1831. The most important change there was the requirement that the Treasurer publish an annual report, along with a copy of the total income and expenditure of the society. These were to be sent to Fellows at least 14 days before the general meeting, with the intent being to ensure the election of competent Officers by making it readily apparent what existing Officers were doing. This was accompanied by a full list of Fellows standing for Council positions, where previously the names had only been announced a couple of days before. As with the other reforms, this helped ensure that Fellows had a chance to vet and properly consider candidates.[36]

In 1850 the society accepted the responsibility of administering a government grant-in-aid of scientific research of £1,000 per year;[37] this was supplemented in the financial year 1876/1877 by a Government Fund of £4,000 per year, with the society acting as the administering body of these funds, distributing grants to scientists.[38][39] The Government Fund came to an end after a period of five years, after which the Government Grant was increased to £4,000 a year in total.[40] This grant has now grown to over £47 million, some £37 million of which is to support around 370 fellowships and professorships.[41][42]

By 1852, the congestion at Somerset House had increased thanks to the growing number of Fellows. Therefore, the Library Committee asked the Council to petition Her Majesty's Government to find new facilities, with the advice being to bring all the scientific societies, such as the Linnean and Geological societies, under one roof. In August 1866, the government announced their intention to refurbish Burlington House and move the Royal Academy and other societies there. The Academy moved in 1867, while other societies joined when their facilities were built. The Royal Society moved there in 1873, taking up residence in the East Wing.[43] The top floor was used as accommodation for the Assistant Secretary, while the library was scattered over every room and the old caretaker's apartment was converted into offices. One flaw was the lack of space for the office staff, which was then approximately eighty.[44]

20th century

On 22 March 1945, the first female Fellows were elected to the Royal Society. This followed a statutory amendment in 1944 that read "Nothing herein contained shall render women ineligible as candidates", and was contained in Chapter 1 of Statute 1. Because of the difficulty of co-ordinating all the Fellows during the Second World War, a ballot on making the change was conducted via the post, with 336 Fellows supporting the change and 37 opposing.[45] Following approval by the Council, Marjory Stephenson and Kathleen Lonsdale were elected as the first female Fellows.[45]

In 1947, Mary Cartwright became the first female mathematician elected to be a Fellow of the Royal Society.[46][47][48] Cartwright was also the first woman to serve on the Council of the Royal Society.[46]

Due to overcrowding at Burlington House, the society moved to Carlton House Terrace in 1967.

21st century

To show support for vaccines against COVID-19, the Royal Society under the guidance of both Nobel prize-winner Venki Ramakrishnan and Sir Adrian Frederick Melhuish Smith added its power to shape public discourse and proposed "legislation and punishment of those who produced and disseminated false information" about the experimental medical interventions. This was brought to popular notice in January 2020 by a retired justice of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, Lord Sumption, who in his broadside wrote "Science advances by confronting contrary arguments, not by suppressing them."[49] The proposal was authored by sociologist Melinda Mills and approved by her colleagues on the "Science in Emergencies Tasking – COVID" in an October 2020 report entitled "COVID-19 vaccine deployment: Behaviour, ethics, misinformation and policy strategies". The SET-C committee favoured legislation from China, Singapore and South Korea, and found that "Singapore, for instance has the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA), with four prominent (criminal) cases within the first months of the COVID-19 outbreak. POFMA also lifted any exemptions for internet intermediaries which legally required social media companies like Google, Facebook, Twitter and Baidu to immediately correct cases of misinformation on their platforms."[50]

Coat of arms

The blazon for the shield in the coat of arms of the Royal Society is in a dexter corner of a shield argent our three Lions of England, and for crest a helm adorned with a crown studded with florets, surmounted by an eagle of proper colour holding in one foot a shield charged with our lions: supporters two white hounds gorged with crowns, with the motto of nullius in verba. John Evelyn, interested in the early structure of the society, had sketched out at least six possible designs, but in August 1662 Charles II told the society that it was allowed to use the arms of England as part of its coat and the society "now resolv'd that the armes of the Society should be, a field Argent, with a canton of the armes of England; the supporters two talbots Argent; Crest, an eagle Or holding a shield with the like armes of England, viz. 3 lions. The words Nullius in verba". This was approved by Charles, who asked Garter King of Arms to create a diploma for it, and when the second charter was signed on 22 April 1663 the arms were granted to the president, council and fellows of the society along with their successors.[51]

The helmet of the arms was not specified in the charter, but the engraver sketched out a peer's helmet (barred helmet) on the final design, which is used. This is contrary to the heraldic rules, as a society or corporation normally has an esquire's helmet (closed helmet); it is thought that either the engraver was ignorant of this rule, which was not strictly adhered to until around 1615, or that he used the peer's helmet as a compliment to Lord Brouncker, a peer and the first President of the Royal Society.[52]

Charter book

Fellows and foreign members are required to sign a book when they join the Royal Society. This book is known as the Charter Book, which has been signed continuously since 1663. All British monarchs have signed the book since then, apart from William and Mary, and Queen Anne.[53] In 2019, the book was digitised.[53]

Motto

The society's motto, Nullius in verba, is Latin for "Take nobody's word for it". It was adopted to signify the fellows' determination to establish facts via experiments and comes from Horace's Epistles, where he compares himself to a gladiator who, having retired, is free from control.[54]

Fellows of the Royal Society (FRS)

The society's core members are the fellows: scientists and engineers from the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth selected based on having made "a substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathematics, engineering science and medical science".[55] Fellows are elected for life and gain the right to use the postnominal Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS). The rights and responsibilities of fellows also include a duty to financially contribute to the society, the right to stand for council posts and the right to elect new fellows.[56] Up to 52 fellows are elected each year and in 2014 there were about 1,450 living members in total.[3] Election to the fellowship is decided by ten sectional committees (each covering a subject area or set of subjects areas) which consist of existing fellows.

The society also elects royal fellows, honorary fellows and foreign members. Royal fellows are those members of the British royal family, representing the British monarchy's role in promoting and supporting the society, who are recommended by the society's council and elected via postal vote. There are currently four royal fellows: The King of the United Kingdom, The Duke of Kent, The Princess Royal, and The Prince of Wales.[3] Honorary fellows are people who are ineligible to be elected as fellows but nevertheless have "rendered signal service to the cause of science, or whose election would significantly benefit the Society by their great experience in other walks of life". Six honorary fellows have been elected to date, including Baroness O'Neill of Bengarve.[57] Foreign members are scientists from non-Commonwealth nations "who are eminent for their scientific discoveries and attainments". Eight are elected each year by the society and also hold their membership for life. Foreign members are permitted to use the post-nominal ForMemRS (Foreign Member of the Royal Society) and as of August 2020 number about 185.[58]

The appointment of fellows was first authorised in the second charter, issued on 22 April 1663, which allowed the president and council, in the two months following the signing, to appoint as fellows any individual they saw fit. This saw the appointment of 94 fellows on 20 May and 4 on 22 June; these 98 are known as the "Original Fellows". After the expiration of this two-month period, any appointments were to be made by the president, council and existing fellows.[59] Many early fellows were not scientists or particularly eminent intellectuals; it was clear that the early society could not rely on financial assistance from the king, and scientifically trained fellows were few and far between. It was, therefore, necessary to secure the favour of wealthy or important individuals for the society's survival.[60] While the entrance fee of £4 and the subscription rate of one shilling a week should have produced £600 a year for the society, many fellows paid neither regularly nor on time.[61] Two-thirds of the fellows in 1663 were non-scientists; this rose to 71.6% in 1800 before dropping to 47.4% in 1860 as the financial security of the society became more certain.[62] In May 1846, a committee recommended limiting the annual intake of members to 15 and insisting on scientific eminence; this was implemented, with the result being that the society now consists exclusively of scientific fellows.[63]

Structure and governance

The society is governed by its council, which is chaired by the society's president, according to a set of statutes and standing orders. The members of council, the president, and the other officers are elected from and by its fellowship.

Council

The council is a body consisting of 20 to 24 Fellows,[64] including the officers (the president, the treasurer, two secretaries—one from the physical sciences, one from life sciences—and the foreign secretary),[65] one fellow to represent each sectional committee and seven other fellows.[66] The council is tasked with directing the society's overall policy, managing all business related to the society, amending, making or repealing the society's standing orders and acting as trustees for the society's possessions and estates. Members are elected annually via a postal ballot, and current standing orders mean that at least ten seats must change hands each year.[67] The council may establish (and is assisted by) a variety of committees,[67] which can include not only fellows but also outside scientists.[66] Under the charter, the president, two secretaries and the treasurer are collectively the officers of the society.[68] The current officers[69] are:

- President: Adrian Smith

- Treasurer: Jonathan Keating

- Biological Secretary: Linda Partridge

- Physical Secretary : Peter Bruce

- Foreign Secretary: Mark Walport and Alison Noble (jointly)

President

The president of the Royal Society is the head of both the society and the council. The details for the presidency were set out in the second charter and initially had no limit on how long a president could serve; under current society statute, the term is five years.[70]

The current president is Adrian Smith, who took over from Venki Ramakrishnan on 30 November 2020.[71] Historically, the duties of the president have been both formal and social. The Cruelty to Animals Act, 1876 left the president as one of the few individuals capable of certifying that a particular experiment on an animal was justified. In addition, the president is to act as the government's chief (albeit informal) advisor on scientific matters. Yet another task is that of entertaining distinguished foreign guests and scientists.[72]

Permanent staff

The society is assisted by a number of full-time paid staff. The original charter provided for "two or more Operators of Experiments, and two or more clerks"; as the number of books in the society's collection grew, it also became necessary to employ a curator. The staff grew as the financial position of the society improved, mainly consisting of outsiders, along with a small number of scientists who were required to resign their fellowship on employment.[73] The current executive director is Dame Julie Maxton DBE.[74]

Functions and activities

The society has a variety of functions and activities. It supports modern science by disbursing over £100 million to fund almost 1,000 research fellowships for both early and late-career scientists, along with innovation, mobility and research capacity grants.[75] Its awards, prize lectures and medals all come with prize money intended to finance research,[76] and it provides subsidised communications and media skills courses for research scientists.[77] Much of this activity is supported by a grant from the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, most of which is channelled to the University Research Fellowships (URF).[41] In 2008, the society opened the Royal Society Enterprise Fund, intended to invest in new scientific companies and be self-sustaining, funded (after an initial set of donations on the 350th anniversary of the society) by the returns from its investments.[78]

Through its Science Policy Centre, the society acts as an advisor to the UK Government, the European Commission and the United Nations on matters of science. It publishes several reports a year, and serves as the Academy of Sciences of the United Kingdom.[79] Since the middle of the 18th century, government problems involving science were irregularly referred to the society, and by 1800 it was done regularly.[80]

Carlton House Terrace

The premises at 6–9 Carlton House Terrace is a Grade I listed building and the current headquarters of the Royal Society, which had moved there from Burlington House in 1967.[81] The ground floor and basement are used for ceremonies, social and publicity events, the first floor hosts facilities for Fellows and Officers of the society, and the second and third floors are divided between offices and accommodation for the President, Executive Director and Fellows.[82]

The first Carlton House was named after Baron Carleton, and was sold to Lord Chesterfield in 1732, who held it on trust for Frederick, Prince of Wales. Frederick held his court there until his death in 1751, after which it was occupied by his widow until her death in 1772. In 1783, the then-Prince of Wales George bought the house, instructing his architect Henry Holland to completely remodel it.

When George became King, he authorised the demolition of Carlton House, with the request that the replacement be a residential area. John Nash eventually completed a design that saw Carlton House turned into two blocks of houses, with a space in between them.[83] The building is still owned by the Crown Estates and leased by the society; it underwent a major renovation from 2001 to 2004 at the cost of £9.8 million, and was reopened by the Prince of Wales on 7 July 2004.[15]

Carlton House Terrace underwent a series of renovations between 1999 and November 2003 to improve and standardise the property. New waiting, exhibition and reception rooms were created in the house at No.7, using the Magna Boschi marble found in No.8, and greenish grey Statuario Venato marble was used in other areas to standardise the design.[82] An effort was also made to make the layout of the buildings easier, consolidating all the offices on one floor, Fellows' Rooms on another and all the accommodation on a third.[84]

Kavli Royal Society International Centre

In 2009 Chicheley Hall, a Grade I listed building located near Milton Keynes, was bought by the Royal Society for £6.5 million, funded in part by the Kavli Foundation.[85] The Royal Society spent several million on renovations adapting it to become the Kavli Royal Society International Centre, a venue for residential science seminars. The centre held its first scientific meeting on 1 June 2010 and was formally opened on 21 June 2010.[86] The Centre was permanently closed on 18 June 2020[87] and the building was sold in 2021.[88]

Publishing

-2.jpg.webp)

Through Royal Society Publishing, the society publishes the following journals:[89]

- Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A (mathematics and the physical sciences)

- Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B (biological sciences)

- Proceedings of the Royal Society A

- Proceedings of the Royal Society B

- Biology Letters

- Open Biology

- Royal Society Open Science

- Journal of the Royal Society Interface

- Interface Focus

- Notes and Records

- Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society

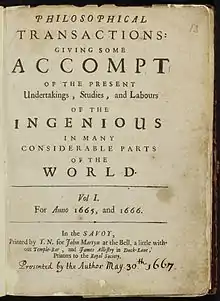

The society introduced the world's first journal exclusively devoted to science in 1665, Philosophical Transactions, and in so doing originated the peer review process now widespread in scientific journals. Its founding editor was Henry Oldenburg, the society's first secretary.[90][91] It remains the oldest and longest-running scientific journal in the world. It now publishes themed issues on specific topics and, since 1886,[92] has been divided into two parts; A, which deals with mathematics and the physical sciences,[93] and B, which deals with the biological sciences.[94]

Proceedings of the Royal Society consists of freely submitted research articles and is similarly divided into two parts.[95] Biology Letters publishes short research articles and opinion pieces on all areas of biology and was launched in 2005.[96] Journal of the Royal Society Interface publishes cross-disciplinary research at the boundary between the physical and life sciences,[97] while Interface Focus,[98] publishes themed issue in the same areas. Notes and Records is the society's journal of the history of science.[99] Biographical Memoirs is published twice annually and contains extended obituaries of deceased Fellows.[100] Open Biology is an open access journal covering biology at the molecular and cellular level. Royal Society Open Science is an open access journal publishing high-quality original research across the entire range of science on the basis of objective peer-review.[101] All the society's journals are peer-reviewed.

In May 2021, the society announced plans to transition its four hybrid research journals to open access[102]

Honours

The Royal Society presents numerous awards, lectures, and medals to recognise scientific achievement.[76] The oldest is the Croonian Lecture, created in 1701 at the request of the widow of William Croone, one of the founding members of the Royal Society. The Croonian Lecture is still awarded on an annual basis and is considered the most important Royal Society prize for the biological sciences.[103] Although the Croonian Lecture was created in 1701, it was first awarded in 1738, seven years after the Copley Medal. The Copley Medal is the oldest Royal Society medal still in use and is awarded for "outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science".[104]

See also

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Royal Fellows of the Royal Society

- List of Fellows of the Royal Society

- List of female Fellows of the Royal Society

- List of presidents of the Royal Society

- Academy of Medical Sciences

- British Academy

- British Association for the Advancement of Science

- History of science

- Laputa, a fictional island full of absurd inventions put by Jonathan Swift in Gulliver's Travels to mock the Royal Society.

- Learned societies

- List of British professional bodies

- List of Royal Societies

- Royal Institution

- Royal Society of Arts

- Royal Academy of Engineering, UK

- Society Islands

- The Baroque Cycle, a series of historical novels by Neal Stephenson, in which many of the founders of the Royal Society appear.

- The Royal Society Range, a mountain range in Antarctica named after the society

- UK Young Academy

- Glossary of areas of mathematics

- Glossary of astronomy

- Glossary of biology

- Glossary of calculus

- Glossary of chemistry

- Glossary of engineering

- Glossary of physics

References

- ↑ "The formal title as adopted in the royal charter" (PDF). royalsociety.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ Ellis Rubinstein, Science Academies in the 21st Century: Can they address the world's challenges in novel ways? Treballs de la SCB. Vol. 63, 2012, pp. 390; PDF Archived 5 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Fellows – Fellowship – The Royal Society". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ↑ Yates, Frances (1984). Collected Essays Vol. III. p. 253.

- ↑ David A. Kronick, The Commerce of Letters: Networks and "Invisible Colleges" in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Europe, The Library Quarterly, Vol. 71, No. 1 (Jan. 2001), pp. 28–43; JSTOR 4309484

- ↑ "JOC/EFR: The Royal Society, August 2004 retrieved online: 2009-05-14". Archived from the original on 11 April 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ↑ "Tallents, Francis (TLNS636F)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ Margery Purver, The Royal Society: Concept and Creation (1967), Part II Chapter 3, The Invisible College.

- ↑ Syfret (1948) p. 75

- 1 2 Syfret (1948) p. 78

- ↑ "London Royal Society". University of St Andrews. Archived from the original on 14 April 2009. Retrieved 8 December 2009.

- ↑ Syfret (1948) p. 79

- ↑ Syfret (1948) p. 80

- ↑ "The Royal Society of London". National Museum of Australia. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- 1 2 "Prince of Wales opens Royal Society's refurbished building". The Royal Society. 7 July 2004. Archived from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

- ↑ Henderson (1941) p. 29

- ↑ Henderson (1941) p. 28

- ↑ Martin (1967) p. 13

- ↑ Hunter (1984) p. 160

- ↑ Hunter (1984) p. 161

- ↑ Hunter (1984) p. 179

- 1 2 Henderson (1941) p.30

- 1 2 "Newton biography". University of St Andrews. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2009.

- ↑ Lyons (April 1939) p.34

- ↑ Martin (1967) p.14

- ↑ Lyons (April 1939) p.35

- ↑ Lyons (April 1939) p.38

- ↑ Lyons (April 1939) p.40

- ↑ Sorrenson (1996) p. 29

- ↑ Sorrenson (1996) p. 31

- ↑ Miller (1998) p. 78

- ↑ Miller (1998) p. 79

- ↑ Miller (1998) p. 85

- ↑ Martin (1967) p. 16

- ↑ Henderson (1941) p. 31

- ↑ Lyons (November 1939) p.92

- ↑ "Government Aid to Scientific Research". Nature. 14 (348): 185–186. 1 June 1876. Bibcode:1876Natur..14..185.. doi:10.1038/014185a0. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 4116633.

- ↑ "Government Grants in Aid of Science". Nature. 15 (383): 369. March 1877. Bibcode:1877Natur..15..369.. doi:10.1038/015369a0. S2CID 4109319.

- ↑ Hall (1981) p.628

- ↑ MacLeod, R. M. (1971). "The Royal Society and the Government Grant: Notes on the Administration of Scientific Research, 1849–1914". The Historical Journal. 14 (2): 337–348. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00009638. JSTOR 2637959. S2CID 159794593. Archived from the original on 3 November 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- 1 2 "Parliamentary Grant". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ↑ "Parliamentary Grant Delivery Plan 2011–15" (PDF). The Royal Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ↑ Martin (1967) p. 17

- ↑ Martin (1967) p. 18

- 1 2 "Admission of Women into the Fellowship of the Royal Society". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 4 (1): 39. 1946. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1946.0006. S2CID 202575203.

- 1 2 Hayman, Walter K. (2000). "Dame Mary (Lucy) Cartwright, D.B.E. 17 December 1900 – 3 April 1998: Elected F.R.S. 1947". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 46: 19. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1999.0070.

- ↑ "Mistress of Girton whose mathematical work formed the basis of chaos theory". Obituaries Electronic Telegraph. 11 April 1998. Archived from the original on 6 November 2004. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ↑ Walter Hayman (1 November 2000). "Dame Mary (Lucy) Cartwright, D.B.E. 17 December 1900 – 3 April 1998". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 46: 19–35. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1999.0070. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ↑ Sumption, Jonathan (7 January 2021). "YouTube censorship is a symptom of a corrosive philosophy". Telegraph Media Group Limited. Archived from the original on 8 January 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ↑ Knapton, Sarah (10 November 2020). "Spreading anti-vaxx myths 'should be made a criminal offence'". Telegraph Media Group Limited. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ↑ J.D.G.D. (1938) p.37

- ↑ J.D.G.D. (1938) p.38

- 1 2 "Turning a new page in the Charter Book | Royal Society". royalsociety.org. Archived from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ↑ "History". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ↑ "Criteria for candidates – Criteria for candidates – The Royal Society". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 7 December 2009. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- ↑ "The rights and responsibilities of Fellows of the Royal Society". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 7 December 2009. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- ↑ "Honorary Fellows". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 7 December 2009. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- ↑ "Foreign Members". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 27 September 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ de Beer (1950) p.172

- ↑ Lyons (1939) p.109

- ↑ Lyons (1939) p.110

- ↑ Lyons (1939) p.112

- ↑ Lyons (1938) p.45

- ↑ "Statutes of the Royal Society" (PDF). The Royal Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ↑ Poliakoff, Martyn. "The Royal Society, the Foreign Secretary, and International Relations". sciencediplomacy.org. Science & Diplomacy. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- 1 2 "How is the Society governed?". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 9 June 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- 1 2 "The Council". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 9 June 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- ↑ Lyons (1940) p. 115

- ↑ "Council". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ↑ "Misogallus on the warpath". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ↑ "Sir Adrian Smith confirmed as President-Elect of the Royal Society". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ↑ "The Presidency of the Royal Society of London". Science. 6 (146): 442–3. 1885. Bibcode:1885Sci.....6..442.. doi:10.1126/science.ns-6.146.442. PMID 17749567.

- ↑ Robinson (1946) p.193

- ↑ "Staff". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ "Grants". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Awards, medals and prize lectures". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

- ↑ "Communication skills and Media training courses". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 3 December 2009. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

- ↑ "The Royal Society Enterprise Fund". The Royal Society Enterprise Fund. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

- ↑ Science Policy Centre – 2010 and beyond. The Royal Society. 2009. p. 3.

- ↑ Hall (1981) p.629

- ↑ "General". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 18 December 2009. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

- 1 2 Fischer (2005) p.66

- ↑ Summerson (1967) p.20

- ↑ Fischer (2005) p.67

- ↑ ""Royal Society snaps up a stately hothouse", Times Online, 29 March 2009". Timesonline.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 November 2023. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ "Opening of The Kavli Royal Society Centre for the Advancement of Science". The Royal Society. 15 September 2010. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ↑ "Milton Keynes wedding venue 'to close permanently' due to impact from coronavirus lockdown". 19 June 2020. Archived from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ↑ Katherine Price (17 March 2021). "Chicheley Hall sold for £7m to Pyrrho Investments". The Caterer. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ↑ "Royal Society Publishing". Royal Society Publishing. Archived from the original on 23 August 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- ↑ Wagner (2006) p. 220-1

- ↑ Select Committee on Science and Technology. "The Origin of the Scientific Journal and the Process of Peer Review". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ↑ "Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London". rstl.royalsocietypublishing.org. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ↑ "Philosophical Transactions A – About the journal". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- ↑ "Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 10 May 2009. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- ↑ "Proceedings A – about the journal". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 3 May 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- ↑ "Biology Letters – about this journal". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 3 May 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- ↑ "Journal of the Royal Society Interface – About". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- ↑ "Interface Focus – About". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 23 December 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ "About Notes and Records". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- ↑ "Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 18 March 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- ↑ "ROYAL SOCIETY OPEN SCIENCE | Open Science". rsos.royalsocietypublishing.org. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ↑ "The Royal Society sets 75% threshold to 'flip' its research journals to Open Access over the next five years". The Royal Society. 13 May 2021. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ↑ "The Croonian Lecture (1738)". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- ↑ "The Copley Medal (1731)". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

Bibliography

- A.C.S. (1938). "Notes on the Foundation and History of the Royal Society". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 1 (1): 32. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1938.0006.

- Bluhm, R.K. (1958). "Remarks on the Royal Society's Finances, 1660–1768". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 13 (2): 82. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1958.0012. S2CID 144772434.

- de Beer, E.S. (1950). "The Earliest Fellows of the Royal Society". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 7 (2): 172. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1950.0014. S2CID 202574293.

- Carré, Meyrick H. "The Formation of the Royal Society" History Today (Aug 1960) 10#8 pp 564–571.

- J.D.G.D. (1938). "The Arms of the Society". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 1 (1): 37. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1938.0007.

- Fischer, Stephanie (2005). "Report: The Royal Society Redevelopment". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 59 (1): 65. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2004.0077. S2CID 71782293.

- Hall, Marie Boas (1981). "Public Science in Britain: The Role of the Royal Society". Isis. 72 (4): 627–629. doi:10.1086/352847. JSTOR 231253. S2CID 143667490.

- Hart, Vaughan (2020). Christopher Wren: In Search of Eastern Antiquity, Yale University Press ISBN 978-1913107079

- Henderson, L.J. (1941). "The Royal Society". Science. 93 (2402): 27–32. Bibcode:1941Sci....93...27H. doi:10.1126/science.93.2402.27. PMID 17772875.

- Hunter, Michael (1984). "A 'College' for the Royal Society: The Abortive Plan of 1667–1668". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 38 (2): 159. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1984.0011. S2CID 144483080.

- Lyons, H.G. (1938). "The Growth of the Fellowship". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 1 (1): 40. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1938.0008.

- Lyons, H.G. (April 1939). "Two Hundred Years Ago. 1739". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 2 (1): 34. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1939.0007.

- Lyons, H.G. (November 1939). "One Hundred Years Ago. 1839". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 2 (2): 92. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1939.0016.

- Lyons, H.G. (1939). "The Composition of the Fellowship and the Council of the Society". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 2 (2): 108. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1939.0017.

- Lyons, H.G. (1940). "The Officers of the Society (1662–1860)". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 3 (1): 116. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1940.0017. S2CID 71384634.

- Martin, D.C. (1967). "Former Homes of the Royal Society". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 22 (1/2): 12. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1967.0002. S2CID 145126489.

- Miller, David Philip (1998). "The 'Hardwicke Circle': The Whig Supremacy and Its Demise in the 18th-Century Royal Society". Notes and Records of the Royal Society. 52 (1): 73. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1998.0036. S2CID 145249420.

- Robinson, H.W. (1946). "The Administrative Staff of the Royal Society, 1663–1861". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 4 (2): 193. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1946.0029.

- Sorrenson, Richard (1996). "Towards a History of the Royal Society in the Eighteenth Century". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 50 (1): 29. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1996.0003. S2CID 144386127.

- Sprat, Thomas (1722). The history of the Royal Society of London: for the improving of natural knowledge. By Tho. Sprat. Samuel Chapman. OCLC 475095951.

- Stark, Ryan. "Language Reform in the Late Seventeenth Century", in Rhetoric, Science, and Magic in Seventeenth-Century England (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2009), 9–46.

- Summerson, John (1967). "Carlton House Terrace". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 22 (1): 20. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1967.0003. S2CID 72906527.

- Syfret, R.H. (1948). "The Origins of the Royal Society". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 5 (2): 75–137. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1948.0017. JSTOR 531306.

- Wagner, Wendy Elizabeth (2006). Rescuing Science from Politics: Regulation and the Distortion of Scientific Research. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521855204.

External links

- Official website

- Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London public domain @Archive.org

- The Royal Society Publishing website

- The Royal Society of London (a brief history)

- Scholarly Societies Project: Royal Society of London

- A visualisation of the Royal Society's publications from 1665 to 2005

- The Royal Society, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Stephen Pumphrey, Lisa Jardine & Michael Hunter (In Our Time, 23 March 2006)

- Digitised copy of the Charter Book