| Rotifera Temporal range: Possible Devonian and Permian records | |

|---|---|

| |

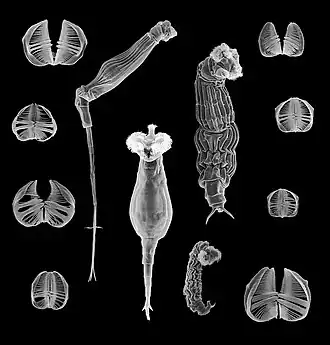

| Bdelloid rotifer (Bdelloidea) | |

| |

| Pulchritia dorsicornuta (Monogononta) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Clade: | Nephrozoa |

| (unranked): | Protostomia |

| (unranked): | Spiralia |

| Clade: | Gnathifera |

| Phylum: | Rotifera Cuvier, 1798 |

| Classes and other subgroups | |

The rotifers (/ˈroʊtɪfərz/, from the Latin rota, "wheel", and -fer, "bearing"), commonly called wheel animals or wheel animalcules,[1] make up a phylum (Rotifera /roʊˈtɪfərə/) of microscopic and near-microscopic pseudocoelomate animals.

They were first described by Rev. John Harris in 1696, and other forms were described by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in 1703.[2] Most rotifers are around 0.1–0.5 mm (0.0039–0.0197 in) long (although their size can range from 50 μm (0.0020 in) to over 2 mm (0.079 in)),[1] and are common in freshwater environments throughout the world with a few saltwater species.

Some rotifers are free swimming and truly planktonic, others move by inchworming along a substrate, and some are sessile, living inside tubes or gelatinous holdfasts that are attached to a substrate. About 25 species are colonial (e.g., Sinantherina semibullata), either sessile or planktonic. Rotifers are an important part of the freshwater zooplankton, being a major foodsource and with many species also contributing to the decomposition of soil organic matter.[3] Most species of the rotifers are cosmopolitan, but there are also some endemic species, like Cephalodella vittata to Lake Baikal.[4] Recent barcoding evidence, however, suggests that some 'cosmopolitan' species, such as Brachionus plicatilis, B. calyciflorus, Lecane bulla, among others, are actually species complexes.[5][6] In some recent treatments, rotifers are placed with acanthocephalans in a larger clade called Syndermata.

In June 2021, biologists reported the restoration of bdelloid rotifers after being frozen for 24,000 years in the Siberian permafrost.[7][8] Early purported fossils of rotifers have been suggested in Devonian[9] and Permian[10] fossil beds.

Taxonomy and naming

Rev. John Harris first described the rotifers (in particular a bdelloid rotifer) in 1696 as "an animal like a large maggot which could contract itself into a spherical figure and then stretch itself out again; the end of its tail appeared with a forceps like that of an earwig".[2] In 1702, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek gave a detailed description of Rotifer vulgaris and subsequently described Melicerta ringens and other species.[11] He was also the first to publish observations of the revivification of certain species after drying. Other forms were described by other observers, but it was not until the publication of Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg's Die Infusionsthierchen als vollkommene Organismen in 1838 that the rotifers were recognized as being multicellular animals.[11]

About 2,200 species of rotifers have been described. Their taxonomy is currently in a state of flux. One treatment places them in the phylum Rotifera, with three classes: Seisonidea, Bdelloidea and Monogononta.[12] The largest group is the Monogononta, with about 1,500 species, followed by the Bdelloidea, with about 350 species. There are only two known genera with three species of Seisonidea.[13]

The Acanthocephala, previously considered to be a separate phylum, have been demonstrated to be modified rotifers. The exact relationship to other members of the phylum has not yet been resolved.[14] One possibility is that the Acanthocephala are closer to the Bdelloidea and Monogononta than to the Seisonidea; the corresponding names and relationships are shown in the cladogram below.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

The Rotifera, strictly speaking, are confined to the Bdelloidea and the Monogononta. Rotifera, Acanthocephala and Seisonida make up a clade called Syndermata.[15]

Etymology

The word rotifer is derived from a Neo-Latin word meaning "wheel-bearer",[16] due to the corona around the mouth that in concerted sequential motion resembles a wheel (though the organ does not actually rotate).

Anatomy

Rotifers have bilateral symmetry and a variety of different shapes. The body of a rotifer is divided into a head, trunk, and foot, and is typically somewhat cylindrical. There is a well-developed cuticle, which may be thick and rigid, giving the animal a box-like shape, or flexible, giving the animal a worm-like shape; such rotifers are respectively called loricate and illoricate. Rigid cuticles are often composed of multiple plates, and may bear spines, ridges, or other ornamentation. Their cuticle is nonchitinous and is formed from sclerotized proteins.

The two most distinctive features of rotifers (in females of all species) are the presence of corona on the head, a structure ciliated in all genera except Cupelopagis and presence of mastax. In the more primitive species, the corona forms a simple ring of cilia around the mouth from which an additional band of cilia stretches over the back of the head. In the great majority of rotifers, however, this has evolved into a more complex structure.

Modifications to the basic plan of the corona include alteration of the cilia into bristles or large tufts, and either expansion or loss of the ciliated band around the head. In genera such as Collotheca, the corona is modified to form a funnel surrounding the mouth. In many species, such as those in the genus Testudinella, the cilia around the mouth have disappeared, leaving just two small circular bands on the head. In the bdelloids, this plan is further modified, with the upper band splitting into two rotating wheels, raised up on a pedestal projecting from the upper surface of the head.[17]

The trunk forms the major part of the body, and encloses most of the internal organs. The foot projects from the rear of the trunk, and is usually much narrower, giving the appearance of a tail. The cuticle over the foot often forms rings, making it appear segmented, although the internal structure is uniform. Many rotifers can retract the foot partially or wholly into the trunk. The foot ends in from one to four toes, which, in sessile and crawling species, contain adhesive glands to attach the animal to the substratum. In many free-swimming species, the foot as a whole is reduced in size, and may even be absent.[17]

Nervous system

Rotifers have a small cerebral ganglion, effectively its brain, located just above the mastax, from which a number of nerves extend throughout the body. The number of nerves varies among species, although the nervous system usually has a simple layout. [17]

The nervous system comprises about 25% of the roughly 1,000 cells in a rotifer.[18]

Rotifers typically possess one or two pairs of short antennae and up to five eyes. The eyes are simple in structure, sometimes with just a single photoreceptor cell. In addition, the bristles of the corona are sensitive to touch, and there are also a pair of tiny sensory pits lined by cilia in the head region.[17]

Retrocerebral organ

Despite over 100 years of research, rotifer anatomy still has many poorly understood components. One of the more mysterious organs in rotifers is the "retrocerebral organ" (RCO), which still remains very enigmatic in its morphology, function, development, and evolution. Lying close to the brain, this organ usually consists of one or more glands and a sac or reservoir. The sac drains into a duct before opening through pores on the uppermost part of the head. Current data shows a wide diversity in structure and potential function. [19] In some species it is reduced or may even be absent completely. Benthic species have larger RCO's than planktonic species. Despite this diversity, positional correspondence of RCOs strongly suggests homology.[17][18][20]

A 2023 study using transmission electron microscopy and confocal laser scanning microscopy has illuminated the fine structure of this organ further. The study, the first of its kind, investigated the RCO in one species, (Trichocerca similis). It was determined to be a syncytial organ, composed of a posterior glandular region, an expansive reservoir, and an anterior duct. The glandular portion has an active cytoplasm with paired nuclei, abundant rough ER, ribosomes, Golgi, and mitochondria. Secretion granules accumulate at the anterior end of the gland where they undergo homotypic fusion to create larger granules with numerous "mesh-like" contents. These contents gradually fuse into tubular secretions that accumulate in the reservoir, awaiting secretion. Cross-striated longitudinal muscles form a partial sleeve around the reservoir and may function to squeeze the secretions through the gland's duct that often penetrates through the cerebral ganglion.[20]

Retrocerebral Organ Secretions

Much like the organ itself, the precise function and biochemical makeup of the secretions is still unknown. The small size of rotifers and small volume of the secretions makes isolation immensely difficult. The secretions have some similarities to the hydrogel secretions that form gelatinous housings in some rotifer species. Ultrastructure analysis of T. similis secretions showed them to be a series of tube-like secretions with a highly filamentous framework. This is highly suggestive of a glycosaminoglycan structure- proteins with negatively charged polysaccharide chains forming proteoglycan molecules. These molecules are standard in vertebrate and invertebrate gelatins such as mucus. [20]

Despite recent advancements in understanding RCO organ and secretion ultrastructure, the exact function of the organ is still ultimately unclear. The leading hypotheses are that the RCO secretes a mucus-like substance that aids in benthic locomotion, adhesion, and/or reproduction (i.e., attachment of eggs to a substrate), although more research is needed to explore function and evaluate the homology between species. [20]

Digestive system

The coronal cilia create a current that sweeps food into the mouth. The mouth opens into a characteristic chewing pharynx (called the mastax), sometimes via a ciliated tube, and sometimes directly. The pharynx has a powerful muscular wall and contains tiny, calcified, jaw-like structures called trophi, which are the only fossilizable parts of a rotifer. The shape of the trophi varies between different species, depending partly on the nature of their diet. In suspension feeders, the trophi are covered in grinding ridges, while in more actively carnivorous species, they may be shaped like forceps to help bite into prey. In some ectoparasitic rotifers, the mastax is adapted to grip onto the host, although, in others, the foot performs this function instead.[17]

Behind the mastax lies an oesophagus, which opens into a stomach where most of the digestion and absorption occurs. The stomach opens into a short intestine that terminates in a cloaca on the posterior dorsal surface of the animal. Up to seven salivary glands are present in some species, emptying to the mouth in front of the oesophagus, while the stomach is associated with two gastric glands that produce digestive enzymes.[17]

A pair of protonephridia open into a bladder that drains into the cloaca. These organs expel water from the body, helping to maintain osmotic balance.[17]

Biology

The coronal cilia pull the animal, when unattached, through the water.

Like many other microscopic animals, adult rotifers frequently exhibit eutely—they have a fixed number of cells within a species, usually on the order of 1,000.

Bdelloid rotifer genomes contain two or more divergent copies of each gene, suggesting a long-term asexual evolutionary history.[21] For example, four copies of hsp82 are found. Each is different and found on a different chromosome excluding the possibility of homozygous sexual reproduction.

Feeding

Rotifers eat particulate organic detritus, dead bacteria, algae, and protozoans. They eat particles up to 10 micrometres in size. Like crustaceans, rotifers contribute to nutrient recycling. For this reason, they are used in fish tanks to help clean the water, to prevent clouds of waste matter. Rotifers affect the species composition of algae in ecosystems through their choice in grazing. Rotifers may compete with cladocera and copepods for planktonic food sources.

Reproduction and life cycle

Rotifers are dioecious and reproduce sexually or parthenogenetically. They are sexually dimorphic, with the females always being larger than the males. In some species, this is relatively mild, but in others the female may be up to ten times the size of the male. In parthenogenetic species, males may be present only at certain times of the year, or absent altogether.[17]

The female reproductive system consists of one or two ovaries, each with a vitellarium gland that supplies the eggs with yolk. Together, each ovary and vitellarium form a single syncitial structure in the anterior part of the animal, opening through an oviduct into the cloaca.[17]

Males do not usually have a functional digestive system, and are therefore short-lived, often being sexually fertile at birth. They have a single testicle and sperm duct, associated with a pair of glandular structures referred to as prostates (unrelated to the vertebrate prostate). The sperm duct opens into a gonopore at the posterior end of the animal, which is usually modified to form a penis. The gonopore is homologous to the cloaca of females, but in most species has no connection to the vestigial digestive system, which lacks an anus.[17]

The phylum Rotifera encloses three classes that reproduce by three different mechanisms: Seisonidea only reproduce sexually; Bdelloidea reproduce exclusively by asexual parthenogenesis; Monogononta reproduce alternating these two mechanisms ("cyclical parthenogenesis" or "heterogony").[22] Parthenogenesis (amictic phase) dominates the monogonont life cycle, promoting fast population growth and colonization. In this phase males are absent and amictic females produce diploid eggs by mitosis which develop parthenogenetically into females that are clones of their mothers.[22] Some amictic females can generate mictic females that will produce haploid eggs by meiosis. Mixis (meiosis) is induced by different types of stimulus depending on species. Haploid eggs develop into haploid dwarf males if they are not fertilized and into diploid "resting eggs" (or "diapausing eggs") if they are fertilized by males.

Fertilization is internal. The male either inserts his penis into the female's cloaca or uses it to penetrate her skin, injecting the sperm into the body cavity. The egg secretes a shell, and is attached either to the substratum, nearby plants, or the female's own body. A few species, such as members of the Rotaria, are ovoviviparous, retaining the eggs inside their body until they hatch.[17]

Most species hatch as miniature versions of the adult. Sessile species, however, are born as free-swimming larvae, which closely resemble the adults of related free-swimming species. Females grow rapidly, reaching their adult size within a few days, while males typically do not grow in size at all.[17]

The life span of monogonont females varies from two days to about three weeks.

Loss of sexual reproduction system

'Ancient asexuals': Bdelloid rotifers are assumed to have reproduced without sex for many millions of years. Males are absent within the species, and females reproduce only by parthenogenesis.

However, a new study provided evidence for interindividual genetic exchange and recombination in Adineta vaga, a species previously thought to be anciently asexual.[23]

Recent transitions: Loss of sexual reproduction can be inherited in a simple Mendelian fashion in the monogonont rotifer Brachionus calyciflorus: This species can normally switch between sexual and asexual reproduction (cyclical parthenogenesis), but occasionally gives rise to purely asexual lineages (obligate parthenogens). These lineages are unable to reproduce sexually due to being homozygous for a recessive allele.[24]

Resting eggs

Resting eggs enclose an embryo encysted in a three-layered shell that protects it from external stressors.[25][26] They are able to remain dormant for several decades and can resist adverse periods (e.g., pond desiccation or presence of antagonists).[27][28] When favourable conditions return and after an obligatory period of diapause which varies among species, resting eggs hatch releasing diploid amictic females that enter into the asexual phase of the life cycle.[22][29]

Anhydrobiosis

Bdelloid rotifer females cannot produce resting eggs, but many can survive prolonged periods of adverse conditions after desiccation. This facility is termed anhydrobiosis, and organisms with these capabilities are termed anhydrobionts. Under drought conditions, bdelloid rotifers contract into an inert form and lose almost all body water; when rehydrated they resume activity within a few hours. Bdelloids can survive the dry state for long periods, with the longest well-documented dormancy being nine years. Rotifers can also undergo other forms of cryptobiosis, notably cryobiosis which results from decreased temperatures. In 2021, researchers collected samples from remote Arctic locations containing rotifers which when thawed revealed living specimens around 24,000 years old.[30] While in other anhydrobionts, such as the brine shrimp, this desiccation tolerance is thought to be linked to the production of trehalose, a non-reducing disaccharide (sugar), bdelloids apparently cannot synthesise trehalose. In bdelloids, a major cause of the resistance to desiccation, as well as resistance to ionizing radiation, is a highly efficient mechanism for repairing the DNA double-strand breaks induced by these agents.[31] This repair mechanism likely involves mitotic recombination between homologous DNA regions.[31]

Predators

Rotifers fall prey to many animals, such as copepods, fish (e.g. herring, salmon), bryozoa, comb jellies, jellyfish, starfish, and tardigrades.[32]

Genome size

The genome size of a bdelloid rotifer, Adineta vaga, was reported to be around 244 Mb.[33] The genomes of Monogononts seem to be significantly smaller than those of Bdelloids. In Monogononta the nuclear DNA content (2C) in eight different species of four different genera ranged almost fourfold, from 0.12 to 0.46 pg.[34] Haploid "1C" genome sizes in Brachionus species range at least from 0.056 to 0.416 pg.[35]

Gallery

Pair of Lepadella rotifers from pond water

Pair of Lepadella rotifers from pond water Locula of the rotifer Keratella cochlearis

Locula of the rotifer Keratella cochlearis

References

- 1 2 Howey, Richard L. (1999). "Welcome to the Wonderfully Weird World of Rotifers". Micscape Magazine. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - 1 2 Harmer, Sidney Frederic & Shipley, Arthur Everett (1896). The Cambridge Natural History. The Macmillan company. pp. 197. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

john harris rotifer.

- ↑ "Rotifers". Freshwater Life. Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ↑ Hendrik Segers (2007). Annotated checklist of the rotifers (Phylum Rotifera), with notes on nomenclature, taxonomy

- ↑ Gómez, Africa; Serra, Manuel; Carvalho, Gary R.; Lunt, David H. (July 2002). "Speciation in ancient cryptic species complexes: evidence from the molecular phylogeny of Brachionus plicatilis (Rotifera)". Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution. 56 (7): 1431–1444. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb01455.x. ISSN 0014-3820. PMID 12206243.

- ↑ Dec 2011 4th Internat. Barcode of Life conference, University of Adelaide

- ↑ Renault, Marion (7 June 2021). "This Tiny Creature Survived 24,000 Years Frozen in Siberian Permafrost - The microscopic animals were frozen when woolly mammoths still roamed the planet, but were restored as though no time had passed". the New York Times. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ Shmakova, Lyubov; Malavin, Stas; Iakovenko, Nataliia; Vishnivetskaya, Tatiana; Shain, Daniel; Plewka, Michael; Rivkina, Elizaveta (June 2021). "A living bdelloid rotifer from 24,000-year-old Arctic permafrost". Current Biology. 31 (11): R712–R713. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.04.077. PMID 34102116. S2CID 235365588.

- ↑ "Spoilt attack in the Lower Devonian".

- ↑ "The Oldest Bdelloid Rotifera from Early Permian sediments of Chamba Valley: A New Discovery". International Journal of Geology, Earth and Environmental Science.

- 1 2 Bourne, A.G. (1907). Baynes, Spencer and W. Robertson Smith (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XXI (Ninth ed.). Akron, Ohio: The Werner Company. p. 8.

- ↑ Barnes, R.S.K.; Calow, P.; Olive, P.J.W.; Golding, D.W. & Spicer, J.I. (2001), The Invertebrates: a synthesis, Oxford; Malden, MA: Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-632-04761-1, p. 98

- ↑ Baqai, Aisha; Guruswamy, Vivek; Liu, Janie & Rizki, Gizem (1 May 2000). "Introduction to the Rotifera". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 27 July 2008.

- ↑ Shimek, Ronald (January 2006). "Nano-Animals, Part I: Rotifers". Reefkeeping.com. Retrieved 27 July 2008.

- ↑ Ruppert, Edward E.; Fox, Richard S & Barnes, Robert D. (2004), Invertebrate zoology : a functional evolutionary approach (7th ed.), Belmont, CA: Thomson-Brooks/Cole, ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1, p. 788ff. – see particularly p. 804

- ↑ Pechenik, Jan A. (2005). Biology of the invertebrates. Boston: McGraw-Hill, Higher Education. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-07-234899-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 272–286. ISBN 978-0-03-056747-6.

- 1 2 Robert Lee Wallace. "Rotifers: Exquisite Metazoans". 2002. doi:10.1093/icb/42.3.660 quote: "What is the function of the retrocerebral organ?"

- ↑ Fontaneto, D., & De Smet, W. H. (2015). Rotifera, chapter 4 Handbook of Zoology, Gastrotricha, Cycloneuralia and Gnathifera, Volume 3, Gastrotricha and Gnathifera Schmidt-Rhaesa, Andreas.

- 1 2 3 4 Hochberg, R., Araújo, T. Q., Walsh, E. J., Mohl, J. E., & Wallace, R. L. (2023). Fine structure of the retrocerebral organ in the rotifer Trichocerca similis (Monogononta). Invertebrate Biology, 142(1), e12396. https://doi.org/10.1111/ivb.12396.

- ↑ Jessica L. Mark Welch, David B. Mark Welch & Matthew Meselson (10 February 2004). "Cytogenetic evidence for asexual evolution of bdelloid rotifers". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (6): 1618–1621. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.1618W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0307677100. PMC 341792. PMID 14747655.

- 1 2 3 Nogrady, T., Wallace, R.L., Snell, T.W., 1993. Rotifera vol.1: biology, ecology and systematics. Guides to the identification of the microinvertebrates of the continental waters of the world 4. SPB Academic Publishing bv, The Hague.

- ↑ Vakhrusheva, O.A.; Mnatsakanova, E.A.; Galimov, Y.R.; et al. (18 December 2020). "Genomic signatures of recombination in a natural population of the bdelloid rotifer Adineta vaga". Nature. 11 (1): 6421. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.6421V. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19614-y. PMC 7749112. PMID 33339818.

- ↑ Claus-Peter Stelzer; Johanna Schmidt; Anneliese Wiedlroither; Simone Riss (20 September 2010). "Loss of sexual reproduction and dwarfing in a small metazoan". PLoS ONE. 5 (9): e12854. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...512854S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012854. PMC 2942836. PMID 20862222.

- ↑ Wurdak, Elizabeth S.; Gilbert, John J.; Jagels, Richard (January 1978). "Fine Structure of the Resting Eggs of the Rotifers Brachionus calyciflorus and Asplanchna sieboldi". Transactions of the American Microscopical Society. 97 (1): 49–72. doi:10.2307/3225684. JSTOR 3225684. PMID 564567.

- ↑ Clément, P.; Wurdak, E. (1991). "Rotifera". In Harrison, F.W.; Ruppert, E.E. (eds.). Microscopic Anatomy of Invertebrates. Aschelminthes, vol. IV. Wiley-Liss. pp. 219–97.

- ↑ Marcus, Nancy H.; Lutz, Robert; Burnett, William; Cable, Peter (January 1994). "Age, viability, and vertical distribution of zooplankton resting eggs from an anoxic basin: Evidence of an egg bank". Limnology and Oceanography. 39 (1): 154–158. Bibcode:1994LimOc..39..154M. doi:10.4319/lo.1994.39.1.0154.

- ↑ Kotani, T.; Ozaki, M.; Matsuoka, K.; Snell, T. W.; Hagiwara, A. (2001). "Reproductive isolation among geographically and temporally isolated marine Brachionus strains". Rotifera IX. pp. 283–290. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-0756-6_37. ISBN 978-94-010-3820-1.

- ↑ García-Roger, Eduardo M.; Carmona, María José; Serra, Manuel (January 2005). "Deterioration patterns in diapausing egg banks of Brachionus (Müller, 1786) rotifer species". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 314 (2): 149–161. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2004.08.023.

- ↑ Shmakova, Lyubov; Malavin, Stas; Iakovenko, Nataliia; Vishnivetskaya, Tatiana; Shain, Daniel; Plewka, Michael; Rivkina, Elizaveta (June 2021). "A living bdelloid rotifer from 24,000-year-old Arctic permafrost". Current Biology. 31 (11): R712–R713. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.04.077. ISSN 0960-9822. S2CID 235365588.

- 1 2 Hespeels B, Knapen M, Hanot-Mambres D, Heuskin AC, Pineux F, LUCAS S, Koszul R, Van Doninck K (July 2014). "Gateway to genetic exchange? DNA double-strand breaks in the bdelloid rotifer Adineta vaga submitted to desiccation" (PDF). J. Evol. Biol. 27 (7): 1334–45. doi:10.1111/jeb.12326. PMID 25105197.

- ↑ Wallace, R.L., T.W. Snell, C. Ricci & T. Nogrady (2006). Rotifera Vol. 1: Biology, ecology and systematics. Guides to the identification of the microinvertebrates of the continental waters of the world 23, 299 pp. Kenobi, Ghent/Backhuys, Leiden

- ↑ Flot, Jean-François; Hespeels, Boris; Li, Xiang; Noel, Benjamin; Arkhipova, Irina; Danchin, Etienne G. J.; Hejnol, Andreas; Henrissat, Bernard; Koszul, Romain; Aury, Jean-Marc; Barbe, Valérie; Barthélémy, Roxane-Marie; Bast, Jens; Bazykin, Georgii A.; Chabrol, Olivier; Couloux, Arnaud; Da Rocha, Martine; Da Silva, Corinne; Gladyshev, Eugene; Gouret, Philippe; Hallatschek, Oskar; Hecox-Lea, Bette; Labadie, Karine; Lejeune, Benjamin; Piskurek, Oliver; Poulain, Julie; Rodriguez, Fernando; Ryan, Joseph F.; Vakhrusheva, Olga A.; Wajnberg, Eric; Wirth, Bénédicte; Yushenova, Irina; Kellis, Manolis; Kondrashov, Alexey S.; Mark Welch, David B.; Pontarotti, Pierre; Weissenbach, Jean; Wincker, Patrick; Jaillon, Olivier; Van Doninck, Karine (August 2013). "Genomic evidence for ameiotic evolution in the bdelloid rotifer Adineta vaga". Nature. 500 (7463): 453–457. Bibcode:2013Natur.500..453F. doi:10.1038/nature12326. hdl:1721.1/87072. PMID 23873043.

- ↑ Stelzer, Claus-Peter (1 March 2011). "A first assessment of genome size diversity in Monogonont rotifers". Hydrobiologia. 662 (1): 77–82. doi:10.1007/s10750-010-0487-1. PMC 7611972. PMID 34764494.

- ↑ Stelzer, Claus-Peter; Riss, Simone; Stadler, Peter (7 April 2011). "Genome size evolution at the speciation level: The cryptic species complex Brachionus plicatilis(Rotifera)". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 11 (1): 90. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-90. PMC 3087684. PMID 21473744.

External links

- Jersabek, C. D. & Leitner, M. F. (2013): The Rotifer World Catalog. World Wide Web electronic publication.

- Introduction to the Rotifera

- Rotifers of Germany and Neighbouring Countries (Website with high-quality photos)

- Rotifers

- Tree of Life Web Project

- Rotifer Videos

- Detailed description of Rotifers

- The Rotifers, by Robert Abernathy, on Project Gutenberg

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.