Amount of Roma by Municipality | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 621,573[1] (2011 census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Wallachia, Bucharest, Moldavia, southeastern Transylvania and Dobrogea | |

| Languages | |

| Vlax Romani and Romanian, Turkish in Dobrogea | |

| Religion | |

Roma, traditionally Țigani (often called "Gypsies" though this term is typically considered a slur), constitute one of Romania's largest minorities. According to the 2011 census, their number was 621,573 people or 3.3% of the total population, being the second-largest ethnic minority in Romania after Hungarians.[1] There are different estimates about the size of the total population of people with Romani ancestry in Romania, varying from 4.6 per cent to over 10 percent of the population, because many people of Romani descent do not declare themselves Roma.[2][3] For example, in 2007 the Council of Europe estimated that approximately 1.85 million Roma lived in Romania,[4] based on an average between the lowest estimate (1.2 to 2.2 million people[5]) and the highest estimate (1.8 to 2.5 million people[6]) available at the time. This figure is equivalent to 8.32% of the population.[7][8]

Origins

Their original name is from the Indian Sanskrit word डोम (doma) and means a member of a Dalit caste of travelling musicians and dancers[9] The Roma originate from northern India,[10][11][12][13][14][15] presumably from the northwestern Indian regions such as Rajasthan[14][15] and Punjab.[14]

The linguistic evidence has indisputably shown that roots of Romani language lie in India: the language has grammatical characteristics of Indian languages and shares with them a big part of the basic lexicon, for example, body parts or daily routines.[16] More exactly, Romani shares the basic lexicon with Gujarati, Hindi and Punjabi. It shares many phonetic features with Marwari, while its grammar is closest to Bengali.[17]

Genetic findings in 2012 suggest the Roma originated in northwestern India and migrated as a group.[11][12][18] According to a genetic study in 2012, the ancestors of present scheduled tribes and scheduled caste populations of northern India, traditionally referred to collectively as the Ḍoma, are the likely ancestral populations of modern European Roma.[19]

In February 2016, during the International Roma Conference, the Indian Minister of External Affairs stated that the people of the Roma community were children of India. The conference ended with a recommendation to the Government of India to recognize the Roma community spread across 30 countries as a part of the Indian diaspora.[20]

Terminology

Their original name is from the Sanskrit word डोम (doma) and means a member of a Dalit caste of travelling musicians and dancers[21] In Romani, the native language of the Roma, the word for "people" is pronounced [ˈroma] or [ˈʀoma] depending on dialect ([ˈrom] or [ˈʀom] in the singular). Since the 1990s, the word has also been used officially in the Romanian language, although it was used by Romani activists in Romania as far back as 1933.[22][23]

There are two spellings of the word in Romanian: rom (plural romi), and rrom (plural rromi). The first spelling is preferred by the majority of Romani NGOs[24] and it is the only spelling accepted in Romanian Academy's Dicționarul explicativ al limbii române.[25] The two forms reflect the fact that for some speakers of Romani there are two rhotic (ar-like) phonemes: /r/ and /ʀ/.[26] In the government-sponsored (Courthiade) writing system /ʀ/ is spelt rr. The final i in rromi is the Romanian (not Romani) plural.

The traditional and colloquial Romanian name for Romani, is "țigani" (cognate with Bulgarian цигани (cigani), Hungarian cigány, Greek ατσίγγανοι (atsinganoi), French tsiganes, Portuguese ciganos, Spanish gitanos, Dutch zigeuner, German Zigeuner, Turkish Çigan, Persian زرگری (zargari), Arabic غجري (ghajri), Italian zingari, Russian цыгане (tsygane), Polish cyganie, Czech cikáni and Kazakh Сыған/ســىــعــان (syǵan)). Depending on context, the term may be considered to be pejorative in Romania.[27]

In 2009–2010, a media campaign followed by a parliamentary initiative asked the Romanian Parliament to accept a proposal to revert the official name of country's Roma (adopted in 2000) to Țigan (Gypsy), the traditional and colloquial Romanian name for Romani, in order to avoid the possible confusion among the international community between the words Roma — which refers to the Romani ethnic minority — and Romania.[28] The Romanian government supported the move on the grounds that many countries in the European Union use a variation of the word Țigan to refer to their Gypsy populations. The Romanian upper house, Senate, rejected the proposal.[29][30]

History and integration

Arrival

Linguistic and historical data indicate that the Roma arrived in the Balkans following a long period within the Byzantine Empire, and that this most likely occurred around 1350. This date coincides with a period of instability in Asia Minor due to the expansion of the Ottoman Turks, which may have been a contributory factor in their migration.[31]

It is probable that the first arrival of Roma in the territory of present-day Romania occurred shortly after 1370, when groups of Roma either migrated or were forcibly transferred north of the Danube, with Roma likely reaching Transylvania, then part of the Kingdom of Hungary, in the final decades of the 14th century.[31] The first written record of Roma in Romanian territory dates to 1385 and is from Wallachia, noting the transfer of a group of Roma to the ownership of the monastery of Prizren, their presence then being documented in Transylvania in 1400, and Moldavia in 1425.[31] It is, however, worth noting that the dates above relate principally to the first arrival of Roma in future Romanian territories, waves of migration from the south continued up until the 18th century, when the northward migration of the Roma, some of whom were Turkish-speaking Muslims, was still occurring.[31]

Slavery period

Romani in Wallachia and Moldavia were, from their arrival in the region, enslaved, a situation which continued until the emancipations of the mid-19th century.[32] The institution of Romani slavery also existed in Transylvania, especially in regions which had undergone a period of control by Wallachian or Moldavian princes, but the majority of Transylvanian Roma were not slaves.[32] One child of a former Roma slave, Ștefan Răzvan, briefly achieved power in Moldavia, ruling as Voivod for part of the year 1595.[32]

The economic contribution of slavery in the Danubian principalities was immense, yet no economic compensation was ever paid to freed slaves.[33] The current state of social and economic exclusion in Romania has its roots in the ideology and practice of slavery, and therefore its effects are still felt today.[34][33][35] Public discussion of Roma slavery remains something of a taboo in modern Romania,[34][33] no museum of Roma history exists, nor are there any monuments or memorials to slavery.[33] Textbooks and the Romanian school curriculum either minimise this and other aspects of Roma history or exclude it entirely.[34][33]

Slavery in Wallachia and Moldavia

The institution of slavery in Wallachia and Moldavia predated the arrival of the Roma in the region, and was at that time principally applied to groups of Tatars or Cumans resident in the territory.[32] Although initially all the Roma were owned by princes, groups of Roma were very quickly transferred to monasteries or boyars, creating the three groups of Roma slaves; princely slaves, monastery slaves and boyar slaves.[32] Any Gypsy without a master would automatically become a princely slave, and any foreign-born Romani passing through the prince's dominion risked being enslaved.[32] The Tatar component of the slave population disappeared in the second half of the 15th century, fusing into the more numerous Roma population.[32] during this period, the Roma were organised into bands composed of 30-40 families. These bands were delineated by profession and named for the nature of their economic activity, examples include gold-washers (aurari), bear-baiters (ursari), musicians (lăutari), and spoon-makers (lingurari).[32]

Slavery in the Danubian Principalities did not generally signify that Romani or Tatar slaves were forced remain on the property of their owners, most Roma remained nomadic but were tied to their owners by certain obligations. Slaves made up the lowest category of society, below the serfs, differing from the latter not in the fact that they were unfree, but in their lack of legal personhood.[32] Slaves were considered wholly property of their owners, and could be transferred, bequeathed, mortgaged or exchanged for goods or services. In addition, any property owned by the slaves could also be appropriated. Slaves could be legally imprisoned or beaten by their masters at any time, but they could not be killed, and slaves resident at the manor of their masters had to be fed and clothed. Some Roma slaves were allowed to travel and earn their own living in exchange for a fixed payment to their owners.[32] Still, the brutality of the slave owners in the Danubian Principalities was well known in Western Europe. Louis-Alexandre de Launay, visiting Wallachia and Moldova, noted that: "the boyars are their absolute masters. At will, they sell them (the Roma) and kill them like cattle. Their children are born slaves regardless of their sex."[36]

Princely slaves were obliged to perform labour for the state and pay special taxes, according to a system based on tradition. These obligations were steadily increased over the period of Roma slavery and were sometimes partially extended to slaves owned by monasteries and boyars. A parallel legal system administered by local Romani leaders and sheriffs existed, as Roma had no access to the law, and any damages caused by Roma to the property or persons of non-Roma were legally the responsibility of their legal owners. Killings of Roma were technically punishable by death, but boyars who killed a slave seem never to have been executed in practice and a Roma who killed another would usually simply be offered to the victim's master as compensation.[32] Although contemporary records do show that Roma slaves were occasionally freed by their masters, this was very unusual.[32]

In the late 18th century, formal legal codes forbidding the separation of married couples were enacted. These codes also prohibited the separation of children from their parents and made marriage between free people and the Roma legal without the enslavement of the non-Roma partner, which had been the practice up to that point. The children of such unions would no longer be considered slaves but free people.[32]

Situation of Roma in Late Medieval and Early Modern Transylvania

The situation of Roma in Transylvania differed from that in Wallachia and Moldavia as a result of the different political conditions which prevailed there. At the time of the arrival of the first Roma, around 1400, the region formed part of the Kingdom of Hungary, becoming an autonomous principality in the mid-sixteenth century before finally falling under the dominion of the Habsburg monarchy at the end of the 17th century.[32]

The region of Făgăraș, bordering Wallachia, was under the control of the Prince of Wallachia until the end of the 15th century, and therefore the institutions of slavery which pertained in that region were identical to those in Wallachia.[32] There is also evidence that slavery was practiced in those areas which were temporarily under the control of the Prince of Moldavia. The only notable difference from the situation in Wallachia and Moldavia was that as well as the three categories of slaves found in those principalities, Roma were owned by Bran Castle, the ownership of whom was later transferred to the town of Braşov. This special regime of slavery in specific regions of Transylvania continued throughout the period of the autonomous principality, before its final abolition under the Habsburgs in 1783.[32]

However, the majority of Roma in Transylvania were not enslaved, they instead constituted a type of royal serf, with obligations of service and tax owed to the state set at a lower level than the non-Roma population.[32] The Roma were also exempted from military service and enjoyed a degree of toleration for their non-Christian religious practices. The economic role of Romani metal-workers and craftsmen was significant in the rural economy. Many Romanis retained their nomadic lifestyle, enjoying the right to camp on crown land, however, over the centuries part of the population settled in Saxon villages, on the edge of towns, or on the estates of boyars. Those who settled on Boyar estates quickly became serfs and integrated into the local population, while those in towns and villages tended to retain their identity and freedom, albeit as a marginalised group.[32]

In the second half of the 18th century, the Habsburg monarchy undertook a series of measures designed to forcibly assimilate the Roma and suppress their nomadic lifestyle. The most severe of these decrees came in 1783 when the emperor Joseph II implemented a raft of policies which included forbidding the Roma from trading horses, living in tents, speaking Romani or even marrying another Romani person. They also finally emancipated the last slaves in Transylvania. The decrees seem to have rarely been implemented in full, which prevented the cultural extermination of the Roma, but they were very effective in promoting the sedentarisation of Gypsies in those areas of today's Romania then under Habsburg control.[32]

Roma slavery immediately prior to emancipation

Until the early 19th century, the Roma of Wallachia and Moldavia remained in conditions of slavery that had changed very little since the 14th century, despite the significant changes which had occurred in other sectors of society. Roma slavery was viewed as an integral part of the social system of the principalities, with the Phanariot rulers strongly influenced by the conservatism of their Ottoman suzerains. Following the replacement of the Phanariots with native princes in 1821, Wallachia and Moldova underwent a period of Westernisation and modernisation, eliminating many of the institutions of the ancien régime, but formally enshrining slavery in the founding acts of the principalities.[37]

As part of this modernisation, boyars owning slaves began to exploit their labour more intensively in a more capitalistic fashion. Romani slaves were employed in agricultural tasks during the summer months, which had not been common practice, forced to work on building sites and even in the factories of the nascent industrial sector. Private owners of slaves, monasteries and even the state frequently hired out their slave workforce for large sums of money. This new capitalistic system of exploitation transformed slaves into goods in the full sense of the term, whereas in the past slaves tended to be sold only in extremis, mass auctions of slaves became commonplace. As a result of this new mode of exploitation, the nomadic lifestyle of the Roma of Moldavia and Wallachia was no longer possible, and, like Transylvanian rom, they became a largely sedentary population. The exact slave population of Wallachia and Moldavia at this time is a matter of some debate, but historian Viorel Achim puts the figure at around 400,000, or 7% of the population.[37]

Emancipation

From the 1830s international and domestic criticism of Roma slavery became increasingly prominent, instigated by events such as the mass slave auctions held in Bucharest. Support for the emancipation of the Roma from within the principalities was marginal in the 1830s, but became generalised among the educated classes in the 1840s, before developing into a well-defined abolitionist movement in the 1850s. Heated debate was conducted in newspapers, with abolitionist voices initially focusing on the material and spiritual poverty endured by the slaves, and the damage this did to the country's image, before adopting arguments based on humanism and liberalism. The economic unproductivity of slave labour was also argued by slavery's critics. During the revolutions of 1848, the Moldavian and Wallachian radicals included abolition of slavery as part of their programmes.[37]

The Wallachian state freed its own slaves in 1843, and this was followed by the emancipation of church slaves in 1847. The government of Barbu Dimitrie Știrbei (1849-1856) introduced gradual restrictions of the freedom of private slave-owners to sell or donate slaves. A regulation was introduced in 1850 which forced slave-owners wishing to sell slaves to do so to the state treasury, which would immediately free them. In 1851 a measure allowing the state to compulsorily purchase mistreated slaves was introduced. The final decree of emancipation, entitled “The law for the emancipation of all Gypsies in the Principality of Wallachia” , was enacted in February 1856, thereby ending slavery in Wallachia. Slaveowners were compensated 10 ducats for each slave they possessed, with the cost of this purchase to be taken from the tax revenues which would be paid by freed slaves. The law obliged Roma to settle in villages, where they could be more easily taxed, thus forcing the last nomadic Romani to become sedentary.[37]

In Moldavia, the implementation of an emancipation law of 1844 liberated state and church slaves, leaving only boyar slaves in the principality. Prince Grigore Alexandru Ghica emancipated the final Moldavian slaves in 1855, setting different rates of compensation dependent on whether the gypsies were nomadic lăieşi (4 ducats) or settled vătraşi and linguari (8 ducats). No compensation was paid for invalids or babies. As in Wallachia, the compensation was funded by the taxes paid by the liberated monastery and state slaves, but in Moldavia this was topped up with funds collected from the clergy. Some slave owners chose to be compensated in bonds, paying 10% annual interest, or with a 10-year exemption from taxation.[37]

In Bessarabia, annexed by the Russian Empire in 1812, the Roma were liberated in 1861. Many of them migrated to other regions of the Empire,[38] while important communities remained in Soroca, Otaci and the surroundings of Cetatea Albă, Chișinău, and Bălți.

From emancipation to 1918

The liberation of the Roma improved the legal status of Romania's Roma, however, they retained their position as the most marginalised sector of Romanian society.[33][34] They frequently continued to work for the same masters, without significant improvement to their material conditions.[33] Roma who did not continue to labour for their former owners often suffered great economic hardship, imprisonment and death from hunger being frequent outcomes.[39] During the first thirty years following liberation, a notable phenomenon of urbanisation occurred, with many Roma who were expelled from their former owners' estates, or who did not wish to adopt a lifestyle which would thrust them into poverty, migrating to towns. This contrasted the situation noted in some other groups of Roma, who adapted fully to this new condition and assimilated into the peasant population, losing their status as Roma both culturally and officially.[37]

The social upheaval of emancipation led to mass Romani emigration from Romanian territory, initially into the Austro-Hungarian empire and thence to Western Europe, Poland, the Russian Empire, Scandinavia and the Americas. This migration was the primary origin of the Vlax Roma populations found worldwide today, although it is likely that some Vlax groups may have migrated out of Romania prior to emancipation. This pattern of Roma emigration continued until after the First World War, with Roma in Bavaria recorded as carrying Romanian passports in the 1920s.[37]

The result of these processes of assimilation and emigration was a relative decline in the percentage of Roma inhabitants resident in Moldavia, Wallachia and Bessarabia. At the time of emancipation, the proportion of the populations of Moldavia and Wallachia who had been slaves was around 7%, between 200,000 and 250,000 people. By the last decade of the 19th century the number of Roma is estimated to have grown to between 250,000 and 300,000, 4-5% of the population.[37]

In 1893, the Hungarian authorities carried out a census of Transylvanian Roma which provides a wealth of information on their social and economic situation in the late 19th century. There is evidence for a similar process of assimilation into the general population as was occurring in Moldavia and Wallachia, with Romani groups adopting a Romanian, Hungarian, Székely or Saxon ethnic identity. However, there is also evidence of Roma retaining their specific identity, even when they had abandoned the Romani language: the census records that 38.1% of Transylvanian Roma spoke Hungarian as their mother tongue, 29.97% spoke Romani, 24.39% spoke Romanian, with smaller numbers speaking Slavic languages or German. Though a largely rural population, Transylvanian Roma were rarely involved in agriculture, more commonly working as artisans or craftsmen, with nomadism almost eliminated by this date.[37]

The inter-war period

After the First World War, Greater Romania was established which included Transylvania, Banat, Bukovina and Bessarabia and other territories which increased the number of ethnic Romani in Romania. However, despite this increase in the absolute number of Roma in the country, the decline in the relative proportion of Roma within Romania continued. The first census in interwar Romania took place in 1930; 242,656 persons (1.6%) were registered as (țigani), this number was lower than the figures recorded in the late 19th century, although it was almost certainly much lower than the real figure. The reason for this relative decline was the continued gradual assimilation of Roma to a Romanian or Hungarian ethnic identity, linked to the status of peasants or smallholder, a process which was accelerated by the land reform carried out following the war.[40]

The traditional Roma economic activities of metalwork and crafts became less tenable during this period, as ethnic Romanians began to adopt trades such as woodworking and competition from manufactured goods increased. The few Roma who retained a nomadic lifestyle tended to abandon their traditional crafts and adopt the role of pedlars, and their traditional lifestyle was made very difficult by police refusal to allow them to camp near villages. These economic and social changes reduced the strength of the traditional clan system and, despite the social and linguistic differences between Roma groups, fostered a common Roma identity.[40]

The period of Romanian democracy, between 1918 and 1938, led to a flowering of Romani cultural, social, and political organisations. In 1933, two competing national Roma representative bodies were founded, the General Association of Gypsies in Romania and the General Union of Roma in Romania. These two organisations were bitter rivals who vied for members and whose leaders launched bitter attacks on each other, with the latter, under the leadership of the self-declared Roma Voivode Gheorghe Niculescu, emerging as the only truly national force. The organisation's stated aim was "the emancipation and reawakening of the Roma nation" so that Roma could live alongside their compatriots "without being ashamed".[40]

The General Union of Roma in Romania enjoyed some successes before its suppression in 1941, even continuing to function to a degree after the establishment of a Royal Dictatorship in 1938. Land was obtained for nomadic Roma, church marriages were organised to legally and spiritually formalise Roma couples, and legal and medical services were provided to Roma. They also convinced the government to allow the Roma freedom of movement within the national territory in order to allow them to practice their trades.[40]

The Royal Dictatorship of Carol II, from 1938 to 1940, adopted discriminatory policies against Jewish Romanians and other national minorities. The strongest anti-Roma attitudes of the 1918-1940 period were found not in politics, but in Academia. Scientific racism was rooted in university departments dedicated to Eugenics and biopolitics, which viewed Romani and Jewish people as a "bioethnic danger" to the Romanian nation. These views would come to the fore politically during the dictatorship of Ion Antonescu (1940-1944).[41]

Persecution during World War II

During 1940, Romania was forced to cede territory to Hungary and the Soviet Union, an event which led to the military coup which installed general Ion Antonescu, first in concert with the fascist Iron Guard, and later as a predominantly military fascist dictatorship allied with Nazi Germany. Antonescu persecuted Roma with increasing severity until the invasion of Romania by the Soviets and his overthrow by the King in 1944.[41] During the Second World War, the regime deported 25,000 Romani to Transnistria; of these many thousands died, with estimates of the exact number ranging from 11,000 to 12,500.[42][41] In all, from the territory of present-day Romania (including Northern Transylvania), 36,000 Romani perished during that time.[43] The mistreatment of Romania Roma during World War II has received scant attention from Romanian historians, despite the wide-ranging historical literature detailing the history of the Antonescu regime.[41]

Deportations to Transnistria

The anti-Roma discourse which had been present in Romanian academia during the 1930s became more prominent as an intellectual current after 1940, with academics who had never previously expressed anti-Roma views now doing so, and eugenicists making more radical demands such as the sterilisation of Roma people to protect Romania's ethnic purity.[41] These views also found expression in the ideology of the "legionary" Iron Guard, who followed the scientists in identifying a "Gypsy Problem" in Romania, however, they were suppressed in January 1941 before any serious anti-roma measures had been enacted.[41] Antonescu's post-legionary regime's declared goal was the "Romanianisation" of Romania's territory, through the ethnic cleansing of minorities, especially Jewish and Roma.[41]

Although it appears that Antonescu initially planned the staged deportation of the entire Roma population to Transnistria, Soviet territory occupied by Romania, only the first stage was ever carried out.[41] The initial wave was composed of Roma who the regime considered a "problem", in May 1942, a police survey was conducted to identify any Romani person without a clear occupation or with criminal convictions, difficulty supporting themself, or any practiced nomadism.[41] Immediately following the survey, any Romani person who fell into any of these categories would be forbidden from leaving their county of residence. The deportation of these individuals and their families was justified on the pretext of combatting criminality occurring during blackouts.[41]

The transportation of all nomadic Romanian Roma was carried out between June and August 1942, and was composed of 11,441 people, 6714 of them children.[41] This deportation also included those nomadic Roma serving in the army, who were returned from the front for transportation.[41] The expulsion of sedentary Roma occurred during September 1942 and was incomplete, including only 12,497 of the 31,438 individuals recorded in the police survey.[41] This group consisted of Roma who were categorised as "dangerous and undesirable" and excluded any romani person who had been mobilised by the military and their families.[41]

The September deportations, which occurred by train, were chaotic and often included individuals who were not intended to be deported, or in some cases, who were not even Roma.[41] Cases were reported of theft and exploitative purchases of goods by police and gendarmes, and the deportees were not permitted to carry sufficient goods for survival in Transnistria.[41] Despite the order to respect family members of serving soldiers, many were deported, leading to protests by Romani soldiers and complaints from the army hierarchy.[41] As well as smaller expulsions in late September and early October, there was some repatriation of individuals and families who had been deported in error, before the deportation of the Roma was halted on 14 October 1942, due to its unpopularity.[41]

Deported Roma were generally settled on the edges of villages in the counties of Golta, Ochakov, Balta and Berezovka, their settlement frequently necessitating the eviction of Ukrainian residents who were billeted in the houses of their neighbours.[41] The economic activity of the Roma was, theoretically, organised systematically by the state, however, in reality there was insufficient demand for labour to occupy them and they were unable to sustain themselves through work.[41] Their high concentration in specific locations resulted in food shortages, as the local occupying authorities had insufficient resources to feed the deportees.[41] The deported Roma suffered great hardship from the beginning due to cold and lack of food, with a high mortality rate being notable from the very beginning of the period of deportation.[41] On occasions Roma colonies received no food rations for weeks on end, and as no clothing was issued to supplement the insufficient supply they had been allowed to bring with them, the Ukrainian winter caused much suffering and many deaths, while healthcare was practically non-existent.[41]

The number of dead from cold and hunger among the transported Roma can not be securely calculated, as no reliable contemporary statistics exist.[41] Transnistria was evacuated by the Romanian army in early 1944, in the face of the advancing Soviet forces. Some Roma travelled back to Romania, whereas others remained in Soviet territory, from where they were likely dispersed into other regions, a factor which makes exact calculations of mortality among the transportees very difficult.[41] Romanian historian Viorel Achim puts the number of dead at around half of those transported, roughly 12,500 people,[41] whereas the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania gives an estimate of 11,000.[42]

The Roma of Northern Transylvania during the Second World war

In August 1940, as part of the Second Vienna Award, control of Northern Transylvania, including of all of Maramureș and part of Crișana, was transferred to Hungary.[44] Discrimination by Hungary against Roma had been common throughout the 1930s, and biannual police raids on Romani settlements were mandated by law.[45] During the course of the war, Hungarian Roma were progressively expelled from urban areas or forced to live in ghettoes.[46]

In March 1944, Hungary was occupied by Nazi Germany, Hungary stepped up its persecution of the Roma and Jewish population, with countless Jewish people deported to concentration camps and many Roma organised into forced labour battalions.[46] Following the replacement in late 1944 of the Horthy government with that of the Arrow Cross Party, the mass deportation of Roma to concentration camps began.[46] Initially the victims were transported to local Hungarian labour camps, from which many were later transferred to Dachau.[46] Massacres of gypsies also occurred in various localities, including one occurring in Nagyszalonta (Salonta) now in Romania.[47]

Of a population of around 100,000 Roma in Hungary, around 50,000 were subjected to forced labour.[46] While the total number of Roma killed in Hungary is still a matter of academic debate, the Columbia Guide to the Holocaust puts the figure at 28,000.[48]

During the communist regime and after 1989

The communist authorities tried to integrate the Roma community, for example by building flats for them. Apart from the 1977 national campaign that confiscated all the gold (particularly jewelry) belonging to the Roma, there are few documents about the particular situation of this ethnic group during Ceaușescu's dictatorship.

.jpg.webp)

.jpeg.webp)

Sometimes the authorities tried to cover up crimes related to racial hatred, so as not to raise the social tension. An example of this is the crime committed by a truck driver named Eugen Grigore, from Iași who, in 1974, to avenge the death of his wife and his three children caused by a group of Roma, drove his truck into a Roma camp, killing 24 people. This fact was made public only in the 2000s.[49]

After the fall of communism in Romania, there were many inter-ethnic conflicts targeting the Roma community, the most famous being the 1993 Hădăreni riots. Other important clashes against Roma happened, from 1989 to 2011, in Turulung, Vârghiș, Cuza Vodă, Bolintin-Deal, Ogrezeni, Reghin, Cărpiniş, Găiseni, Plăieşii de Sus, Vălenii Lăpuşului, Racşa, Valea Largă, Apața, Sânmartin, Sâncrăieni and Racoş.[50] During the June 1990 Mineriad, a group of protesters organized a pogrom in the Roma neighborhoods of Bucharest. According to the press, the raids resulted in the destruction of apartments and houses, beatings of men and assaults of women of Roma ethnicity.[50]

Many politicians have also made some offensive statements against the Roma people, such as the president of that time Traian Băsescu, who, in 2007, called a Roma journalist "stinky Gypsy".[51] Later in 2020, during a TV show, Băsescu expressed objections about the use of the term "Roma" instead of "Gypsy", which according to him was "artificially created during the 90s" and "produces confusion with Romanians living abroad".[52] He added that the Roma people created a bad image of Romania, and that the "(criminal) Gypsy groups need to understand that they cannot be tolerated with their way of life".[52] Following these affirmations, the CNCD fined him.[52][53]

In November 2011, the mayor of the city of Baia Mare, Cătălin Cherecheș, decided to build a wall in a neighborhood inhabited by a Roma community. The National Anti-Discrimination Council fined the mayor in 2011 and in 2020 for not demolishing the wall, despite the several orders in this regard.[54][55] Also in 2020, the mayor of Târgu Mureș, Dorin Florea, complained that Mureș County has the biggest number of Roma and that they are "a serious problem for Romania".[56] Sorin Lavric, a senator member of the far-right AUR party, stated that the Roma are "a social plague".[57]

A 2000 EU report about Romani said that in Romania... the continued high levels of discrimination are a serious concern.. and progress has been limited to programmes aimed at improving access to education.[58]

Various international institutions, such as the World Bank, the Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB), and the Open Society Institute (OSI) launched the 2005-2015 Decade for Roma Inclusion.[59] To this, followed the EU Decade of Roma Inclusion [60] to combat this and other problems. The integration of the Roma is made difficult also due to a great economic and social disparity; according to the 2002 census, Roma are the ethnic group with the highest percentage of illiteracy (25.6%), with only the Turkish minority having a similarly high percentage (23.7%).[61] Within the Romanian education system there is discrimination and segregation, which leads to higher drop-out rates and lower qualifications for the Romani students.[62] The life expectancy of the Romani minority is also 10 years lower than the Romanian average.[62]

The accession of Romania to the European Union in 2007 led many members of the Romani minority, the most socially disadvantaged ethnic group in Romania, to migrate en masse to various Western European countries (mostly to Spain, Italy, Austria, Germany, France, Belgium, United Kingdom, Sweden) hoping to find a better life. The exact number of emigrants is unknown. In 2007 Florin Cioabă, an important leader of the Romani community (also known as the "King of all Gypsies") declared in an interview that he worried that Romania may lose its Romani minority.[63] However, the next population census in 2011 showed a substantial rise in those recording Romani ethnicity.[1]

According to some studies, Roma people make 17% of the adult prison population and 40% of the juvenile inmates in Romania.[64] This over-representation makes this group a favorite target for mass media attacks and discriminatory practices.[65] Another study conducted in six Romanian prisons found that 21% of the inmates were Roma, many more than expected based on any official or unofficial statistics on ethnic composition.[66]

The Pro Democrația association in Romania revealed that 94% of the questioned persons believe that the Romanian citizenship should be revoked to the ethnic Roms who commit crimes abroad.[67] Another survey revealed that 68% of Romanians think that Roma people commit most crimes, 46% think that they are thieves, while 43% lazy and dirty, and 36% believe that the Roma community might become a threat to Romania.[68]

In another survey made in 2013 by IRES, 57% respondents stated that they generally don't trust people of Roma ancestry and only 17% said to have a Roma friend.[69] Still, 57% said that this ethnic group is not discriminated in Romania, 59% claimed that the Roma should not receive help from the state, and that Roma people are poor because they don't like to work (72%) and that most of them are thugs (61%).[69] IRES published in 2020 a survey which revealed that 72% of Romanians don't trust Roma people and have a negative opinion about them.[70]

In the context of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, there are some reports of discrimination against Ukrainian Roma who took refuge in Romania.[71][72][73]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1887 | 200,000 | — |

| 1930 | 262,501 | +31.3% |

| 1948 | 53,425 | −79.6% |

| 1956 | 104,216 | +95.1% |

| 1966 | 64,197 | −38.4% |

| 1977 | 227,398 | +254.2% |

| 1992 | 401,087 | +76.4% |

| 2002 | 535,140 | +33.4% |

| 2011 | 621,573 | +16.2% |

| 2022 | 569,477 | −8.4% |

_Romania_2002.png.webp)

| County | Romani population (2011 census) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mureș | 46,947 | 8.52% |

| Călărași | 22,939 | 7.48% |

| Sălaj | 15,004 | 6.69% |

| Bihor | 34,640 | 6.02% |

| Giurgiu | 15,223 | 5.41% |

| Dâmbovița | 27,355 | 5.27% |

| Ialomița | 14,278 | 5.21% |

| Satu Mare | 17,388 | 5.05% |

| Dolj | 29,839 | 4.52% |

| Sibiu | 17,946 | 4.52% |

| Buzău | 20,376 | 4.51% |

| Alba | 14,292 | 4.17% |

| Bistrița-Năsăud | 11,937 | 4.17% |

| Mehedinți | 10,919 | 4.11% |

| Arad | 16,526 | 4.04% |

| Ilfov | 15,634 | 4.02% |

| Covasna | 8,267 | 3.93% |

| Vrancea | 11,966 | 3.52% |

| Brașov | 18,519 | 3.37% |

| Cluj | 22,531 | 3.26% |

| Galați | 16,990 | 3.17% |

| Argeș | 16,476 | 2.69% |

| Brăila | 8,555 | 2.66% |

| Maramureș | 12,211 | 2.55% |

| Bacău | 15,284 | 2.48% |

| Prahova | 17,763 | 2.33% |

| Olt | 9,504 | 2.18% |

| Teleorman | 8,198 | 2.16% |

| Timiș | 14,525 | 2.12% |

| Gorj | 6,698 | 1.96% |

| Suceava | 12,178 | 1.92% |

| Vâlcea | 6,939 | 1.87% |

| Hunedoara | 7,475 | 1.79% |

| Harghita | 5,326 | 1.71% |

| Caraș-Severin | 7,272 | 1.70% |

| Tulcea | 3,423 | 1.61% |

| Vaslui | 5,913 | 1.50% |

| Iași | 11,288 | 1.46% |

| Neamț | 6,398 | 1.36% |

| Bucharest | 23,973 | 1.27% |

| Constanța | 8,554 | 1.25% |

| Botoșani | 4,155 | 1.01% |

| Total[74] | 621,573 | 3.09 % |

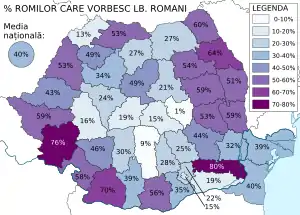

Language

According to the 2011 census, there are 245,677 people whose native language is romani, this represents just under 40% of the ethnic population. However, this number has shrunk to 199,050 according to the 2021 census[75] results, representing just over 33% of the ethnic population. Over half of the Roma (approx. 61%) speak Romanian as their native language, the rest (around 8-9%) speaking the Hungarian language.[76] Both the Roma and the Romanian languages are of the Indo-European language family, while the Hungarian is a Uralic one. The Roma language shares the most lexical similarities with Punjabi and Hindi, the most phonological similarities with Bengali and its grammar structure closely resembles the one found in Merwari. Unsurprisingly, their language is Indo-Aryan, as they originally came from what is today part of east India's Rajasthan, Haryana and Punjab.[77][78][79]

The following spreadsheet contains information regarding the native languages of the ethnic Romani population. Please note that information might not be fully accurate as there is a reasonable population of Romanis who consider themselves as part of the majority population.

| County | Romani population (2011 census) | Romani language | Romanian language | Hungarian language |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alba | 14,292 | 24% | 75% | 1% |

| Arad | 16,526 | 43% | 54% | 3% |

| Argeș | 16,476 | 9% | 91% | 0% |

| Bacău | 15,284 | 59% | 40% | 1% |

| Bihor | 34,640 | 53% | 12% | 35% |

| Bistrița-Năsăud | 11,937 | 27% | 72% | 1% |

| Botoșani | 4,155 | 60% | 40% | 0% |

| Brașov | 18,519 | 15% | 84% | 1% |

| Brăila | 8,555 | 32% | 68% | 0% |

| Bucharest | 23,973 | 15% | 85% | 0% |

| Buzău | 20,376 | 44% | 56% | 0% |

| Caraș-Severin | 7,272 | 76% | 22% | 2% |

| Călărași | 22,939 | 19% | 81% | 0% |

| Cluj | 22,531 | 34% | 59% | 7% |

| Constanța | 8,554 | 40% | 60% | 0% |

| Covasna | 8,267 | 1% | 29% | 70% |

| Dâmbovița | 27,355 | 28% | 72% | 0% |

| Dolj | 29,839 | 70% | 30% | 0% |

| Galați | 16,990 | 59% | 41% | 0% |

| Giurgiu | 15,223 | 35% | 65% | 0% |

| Gorj | 6,698 | 46% | 54% | 0% |

| Harghita | 5,326 | 21% | 0% | 79% |

| Hunedoara | 7,475 | 16% | 81% | 3% |

| Ialomița | 14,278 | 80% | 20% | 0% |

| Iași | 11,288 | 64% | 46% | 0% |

| Ilfov | 15,634 | 22% | 78% | 0% |

| Maramureș | 12,211 | 53% | 41% | 6% |

| Mehedinți | 10,919 | 58% | 42% | 0% |

| Mureș | 46,947 | 49% | 21% | 30% |

| Neamț | 6,398 | 54% | 46% | 0% |

| Olt | 9,504 | 39% | 61% | 0% |

| Prahova | 17,763 | 25% | 75% | 0% |

| Sălaj | 15,004 | 49% | 41% | 10% |

| Satu Mare | 17,388 | 13% | 12% | 75% |

| Sibiu | 17,946 | 19% | 80% | 1% |

| Suceava | 12,178 | 27% | 73% | 0% |

| Teleorman | 8,198 | 56% | 44% | 0% |

| Timiș | 14,525 | 59% | 40% | 1% |

| Tulcea | 3,423 | 39% | 61% | 0% |

| Vâlcea | 6,939 | 30% | 70% | 0% |

| Vaslui | 5,913 | 51% | 49% | 0% |

| Vrancea | 11,966 | 53% | 47% | 0% |

| Total[74] | 621,573 | 3.09 % |

Status of language

According to the constitution of Romania, under law 57/2019, titl. III, art. 94, alin. 1, those communes in which any national (ethnic) minority of Romania, whose proportion of the commune's population is equal to or exceeds 20%, must provide services and inscriptions in that nation's language.[80][81] However this is not carried into practice. On the one hand, this law is respected in the cases of most national minorities (e.g.: Hungarian, German etc.). On the other hand, in communes where the ethnic Romani population (e.g.: Vâlcele, Ormeniş) clearly exceeds that threshold, no inscriptions nor services are available in the Romani language. Moreover, in the village of Crăciunești the population of whose native language is Romani form an absolute majority, and, still, none of the inscriptions are in Romani, only in the official language of the state, Romanian, and in another minority language whose population also surpasses 20%, Hungarian. Furthermore, education is unavailable in all, except for one school in Timiș County.[82] In the other schools, medium of instruction is Romanian, in some cases Hungarian. There are also a few schools, where they teach the language in the afternoons. However, it is still not used in other classes.

Segregation

In Romania there are 2,315 Roma segregated areas, most located on the outskirts of cities, but they can be found in villages as well. These segregated areas typically have a Roma population of almost 100%. The living conditions in these areas are extremely poor: most houses are unmaintained, a number do not even have any services, let alone building permits, with 4.5 people per house on average, a number twice as high as the Romanian one. The vast majority of these segregated areas are predominantly Romanian-speaking, such as the largest segregated area, in Săcele), with over 10,000 people living in it, according to unofficial estimates.[83] Only a minority of these districts are Hungarian or Roma-speaking. The following spreadsheet contains information regarding the largest predominantly Hungarian-speaking Romani segregated areas.[84]

| Locality name (RO) | Locality name (HU) | Name of segregated area | Population | Percentage of Hungarian speakers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Târgu-Mureș | Marosvásárhely | Hidegvölgy | 2500 | 85% |

| Săcueni | Székelyhíd | Dankó Pista | 1870 | 100% |

| Sfântu-Gheorghe | Sepsiszentgyörgy | Őrkő | 1830 | 100% |

| Diosig | Diószeg | Sziget | 1620 | 96% |

| Boroșneu Mare | Nagyborosnyó | Cigányrét | 1222 | 100% |

| Ardud | Erdőd | erdődi cigánytelep | 1135 | 100% |

| Acâș | Ákos | ákosi cigánytelep | 920 | 100% |

| Ghelința | Gelence | Cigányszer | 860 | 100% |

| Ojdula | Ozsdola | Kishilib | 770 | 100% |

| Marghita | Margitta | Oncsa-telep | 758 | 97% |

| Valea Crișului | Sepsikőröspatak | sepsikőröspataki cigánytelep | 689 | 100% |

| Tășnad | Tasnád | tasnádi cigánytelep | 650 | 77% |

| Cidreag | Csedreg | Tanya | 638 | 94% |

And the partially Hungarian-speaking segregated areas:

| Locality name (RO) | Locality name (HU) | Name of segregated area | Population | Percentage of Hungarian speakers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluj-Napoca | Kolozsvár | Patarét | 3000 | 16% |

| Turda | Torda | tordai cigánytelep | 1200 | 7% |

| Doboșeni | Székelyszáldobos | székelyszáldobosi cigánytelep | 1148 | 26% |

| Glodeni | Marossárpatak | Szerbia | 996 | 96% (L2 speakers, native:Romani) |

| Zagon | Zágon | Lingurár-telep | 850 | 26% |

| Bahnea | Bonyha | Cigánysereg | 829 | 22% |

| Vânători | Vadász | Gödör | 800 | 18% |

| Band | Mezőbánd | Kis Telep | 780 | 42% |

| Hrip | Hirip | hiripi cigánytelep | 643 | 92% |

| Baia Mare | Nagybánya | Alsófernezely | 631 | 19% |

| Sighișoara | Segesvár | Parângului | 627 | 27% |

| Vânători | Héjjasfalva | héjjasfalvi cigánytelep | 650 | 15% |

Religion

According to the 2011 census, 69.9% of Roma are Orthodox Christians, 18.4% Pentecostals, 3.8% Roman Catholics, 3% Reformed, 1.1% Greek Catholics, 0.9% Baptists, 0.8% Seventh-Day Adventists, while the rest belong to other religions such as Islam and Lutheranism.[85]

Cultural influence

Notable Romanian Romani musicians and bands include Grigoraş Dinicu, Johnny Răducanu, Ion Voicu, Taraf de Haïdouks, Connect-R, Andra and Nicole Cherry. The musical genre manele, a part of Romanian pop culture, is often sung by Romani singers in Romania and has been influenced in part by Romani music, but mostly by Oriental music brought in Romania from Turkey during the 19th century. Romanian public opinion on the subject varies from support to outright condemnation.

Self-proclaimed "Romani royalty"

The Romani community has:

- An "Emperor of Roma from Everywhere", as Iulian Rădulescu proclaimed himself.[86] In 1997, Iulian Rădulescu announced the creation of Cem Romengo – the first Rom state in Târgu Jiu, in southwest Romania. According to Rădulescu, "this state has a symbolic value and does not affect the sovereignty and unity of Romania. It does not have armed forces and does not have borders". According to the 2002 population census, in Târgu Jiu there are 96.79% Romanians (93,546 people), 3.01% (Roma) (2,916 people) and 0.20% others.[87]

- A "King of Roma". In 1992, Ioan Cioabă proclaimed himself King of Roma at Horezu, "in front of more than 10,000 Rroms" (according to his son's declaration). His son, Florin Cioabă, succeeded him as king.[88]

- An "International King of Roma". On August 31, 2003, according to a decree issued by Emperor Iulian, Ilie Stănescu was proclaimed king. The ceremony took place in Curtea de Argeş Cathedral, the Orthodox Church where Romania's Hohenzollern monarchs were crowned and are buried. Ilie Stănescu died in December, 2007.[89]

Image gallery

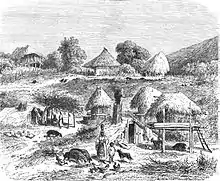

A șatră or village peopled by members of the Romani community of Romania

A șatră or village peopled by members of the Romani community of Romania Purported bulibașa (head of a Romani community)

Purported bulibașa (head of a Romani community) Romanian president Traian Băsescu (left) at a meeting with the representatives of the Romani minority organizations (right)

Romanian president Traian Băsescu (left) at a meeting with the representatives of the Romani minority organizations (right) An example wealthy Romani's house, termed Romani Palace, pictured here in Turda, Cluj County

An example wealthy Romani's house, termed Romani Palace, pictured here in Turda, Cluj County Type of houses owned by wealthy Romani families in Buzescu

Type of houses owned by wealthy Romani families in Buzescu Nazi era image. Posed photo of some NSDAP leaders in 1941, with Romani flower sellers.

Nazi era image. Posed photo of some NSDAP leaders in 1941, with Romani flower sellers. Gábor Hungarian speaking Gypsies from Transylvania

Gábor Hungarian speaking Gypsies from Transylvania

Notable people

- Florin Cioabă, former king of the Gypsies

- Mădălin Voicu, politician

- Ion Voicu, violinist and conductor, the father of Mădălin Voicu

- Johnny Răducanu, jazz musician

- Damian Drăghici, nai player

- Andra, singer

- Ștefan Bănică, actor, singer

- Ștefan Bănică Jr., actor, singer

- Cornelia Catangă, fiddle-singer

- Nicolae Guţă, manele singer

- Adrian Minune, manele singer

- Florin Salam, manele singer

- Vali Vijelie, manele singer

- Sandu Ciorbă, Gipsy music singer

- Connect-R, singer

- Nicole Cherry, singer

- Bănel Nicoliţă, footballer

- Marian Simion, Olympic boxer

- Dorel Simion, Olympic boxer

- Florin "Rambo" Lambagiu, kickboxer

- Ioana Rudăreasa, Romanian-Roma abolitionist

- Mircea Lucescu, football coach

- Daniel Dumitrescu, olympic boxer

See also

- National Agency for the Roma, an agency of the Romanian government dealing with Roma affairs

- Slavery in Romania

- List of towns in Romania by Romani population

- Antiziganism

- 2006 Ferentari riot

References

- 1 2 3 "Romanian 2011 census" (PDF). Recensamantromania.ro (in Romanian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-05-09. Retrieved 2011-12-10.

- ↑ Margaret Beissinger, Speranta Radulescu, Anca Giurchescu, Manele in Romania: Cultural Expression and Social Meaning in Balkan Popular Music, Rowman & Littlefield, 2016, p. 33, ISBN 9781442267084

- ↑ Holly Cartner, Destroying Ethnic Identity: The Persecution of Gypsies in Romania, a Helsinki Watch Report Human Rights Watch, 1991, p. 5, ISBN 9781564320377

- ↑ Council of Europe - Roma and Travellers

- ↑ Council of Europe, doc. GT-ROMS(2003)9-prov. (restricted) 17 September 2003.

- ↑ Liégeois, Jean-Pierre (1994). "Roma, Gypsies, Travellers", p. 34.

- ↑ "Facts and Figures: National strategy for Roma Integration". European Commission. European Union. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ↑ "Roma inclusion in Romania". European Commission.

- ↑ Rama Sharma (1995). Bhangi, Scavenger in Indian Society: Marginality, Identity, and Politicization of the Community. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 126. ISBN 978-8185880709.

- ↑ Hancock, Ian F. (2005) [2002]. We are the Romani People. Univ of Hertfordshire Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-902806-19-8: ‘While a nine century removal from India has diluted Indian biological connection to the extent that for some Roma groups, it may be hardly representative today, Sarren (1976:72) concluded that we still remain together, genetically, Asian rather than European’

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - 1 2 Mendizabal, Isabel; et al. (6 December 2012). "Reconstructing the Population History of European Romani from Genome-wide Data". Current Biology. 22 (24): 2342–2349. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.039. hdl:10230/25348. PMID 23219723.

- 1 2 Sindya N. Bhanoo (11 December 2012). "Genomic Study Traces Roma to Northern India". New York Times.

- ↑ Current Biology.

- 1 2 3 Meira Goldberg, K.; Bennahum, Ninotchka Devorah; Hayes, Michelle Heffner (2015-09-28). Flamenco on the Global Stage: Historical, Critical and Theoretical Perspectives - K. Meira Goldberg, Ninotchka Devorah Bennahum, Michelle Heffner Hayes. McFarland. p. 50. ISBN 9780786494705. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- 1 2 Dorian, Frederick; Duane, Orla; McConnachie, James (1999). World Music: Africa, Europe and the Middle East. Rough Guides. p. 147. ISBN 9781858286358. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- ↑ Šebková, Hana; Žlnayová, Edita (1998), Nástin mluvnice slovenské romštiny (pro pedagogické účely) (PDF), Ústí nad Labem: Pedagogická fakulta Univerzity J. E. Purkyně v Ústí nad Labem, p. 4, ISBN 978-80-7044-205-0, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04

- ↑ Hübschmannová, Milena (1995). "Romaňi čhib – romština: Několik základních informací o romském jazyku". Bulletin Muzea Romské Kultury. Brno: Muzeum romské kultury (4/1995).

Zatímco romská lexika je bližší hindštině, marvárštině, pandžábštině atd., v gramatické sféře nacházíme mnoho shod s východoindickým jazykem, s bengálštinou.

- ↑ "5 Intriguing Facts About the Roma". Live Science. 23 October 2013.

- ↑ Rai, N; Chaubey, G; Tamang, R; Pathak, AK; Singh, VK; et al. (2012), "The Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup H1a1a-M82 Reveals the Likely Indian Origin of the European Romani Populations", PLOS ONE, 7 (11): e48477, Bibcode:2012PLoSO...748477R, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048477, PMC 3509117, PMID 23209554

- ↑ "Can Romas be part of Indian diaspora?". khaleejtimes.com. 29 February 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ↑ Rama Sharma (1995). Bhangi, Scavenger in Indian Society: Marginality, Identity, and Politicization of the Community. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 126. ISBN 978-8185880709.

- ↑ Ziua Activistului Rom, retrieved 2009-01-28

- ↑ "Roma, Sinti, Gypsies, Travellers...The Correct Terminology about Roma". In Other Words Project. 2014-07-19. Archived from the original on 2014-07-19. Retrieved 2021-04-29.

- ↑ Minoritatea Roma – cea mai importanta minoritate din Europa. Romanes.ro. Retrieved on 2012-01-15. Archived May 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "rom". Dicționarul explicativ al limbii române (in Romanian). Academia Română, Institutul de Lingvistică "Iorgu Iordan", Editura Univers Enciclopedic. 1988.

- ↑ Matras, Yaron (2005). Romani: A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521023306.

- ↑ Popescu, Eugenia (2011-07-19). "Discriminarea se invata... in familie" [Discrimination is learned ... in the family]. cronicaromana.ro. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19.

- ↑ Antoniu, Gabriela (2 March 2009). "Propunere Jurnalul Naţional: "Ţigan" în loc de "rom"" [National Journal Proposal: "Gypsy" instead of "Roma"]. jurnalul.ro. Archived from the original on 2014-07-12.

- ↑ Murray, Rupert Wolfe (2010-12-08). "Romania's Government Moves to Rename the Roma". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2021-04-29.

- ↑ Romania Declines to Turn Roma Into 'Gypsies' at balkaninsight.com

- 1 2 3 4 Achim, Viorel (2013). "Chapter I. The arrival of the Gypsies on the territory of Romania". The Roma in Romanian History. CEUP collection. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 9786155053931. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Achim, Viorel (2013). "Chapter II. The gypsies in the Romanian lands in the Middle Ages: Slavery". The Roma in Romanian History. CEUP collection. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 9786155053931. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Necula, Ciprian (2012). "The cost of Roma slavery". Perspective Politice. 5 (2). Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Mircescu, Gabriella (1700). Between Ethnonationalism, Social Exclusion and Multicultural Policies. Freiburg: University of Freiburg, Thesis. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.466.589.

- ↑ Prisacariu, Roxana (2015). "Swiss immigrants' integration policy as inspiration for the Romanian Roma inclusion strategy" (PDF). Institute for Federalism. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ↑ Maria Holban; Ștefan Andreescu (1968). "Călători străini despre Țările Române" (in Romanian). 1. Bucharest: Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Achim, Viorel (2013). "Chapter III. Emancipation". The Roma in Romanian History. CEUP collection. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 9786155053931. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ↑ Ion Nistor, Istoria Basarabiei, Humanitas, Bucuresti, 1991

- ↑ Cărtărescu, Mircea (2007). "Die Zigeuner – ein Rumänisches Problem". Neue Zürcher Zeitung.

- 1 2 3 4 Achim, Viorel (2013). "Chapter IV. The Gypsies in inter-war Romania". The Roma in Romanian History. CEUP collection. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 9786155053931. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Achim, Viorel (2013). "Chapter V. The policy of the Antonescu regime with regard to the Gypsies". The Roma in Romanian History. CEUP collection. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 9786155053931. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- 1 2 The report of the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania - The Deportation of the Roma and their treatment in Transnistria November 11, 2004 (PDF), from Jewish Virtual Library

- ↑ Society for Threatened Peoples. Gfbv.it (2004-02-25). Retrieved on 2012-01-15.

- ↑ Árpád E. Varga, Transylvania's History Archived 2017-06-09 at the Wayback Machine at Kulturális Innovációs Alapítvány

- ↑ Kemény, István (2005). "History of Roma in Hungary, pp. 1-69: Kemény, I.". Roma of Hungary (PDF). Boulder. p. 47.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Baumgartner, Gerhard. "Hungary". Voices of the victims. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ↑ "Társadalmi és etnikai konfliktusok a 19-20. században – Konfliktustérképek (Integrált Térinformatikai Rendszer) / A térképen elérhető adatpontok leírásai /Roma holokauszt: deportálások, tömeggyilkosságok 1944-1945". Regi.tankonyvtar.hu. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ↑ Niewyk, Donald L. (2000). The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust. Columbia University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-231-11200-0.

- ↑ Ionuţ Benea (June 5, 2015). "Povestea şoferului care a ucis 24 de ţigani cu un camion. Securitatea a dosit măcelul, de frica conflictelor interetnice". Adevărul (in Romanian). Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- 1 2 Gabriel Sala (February 25, 2017). "Conflicte interetnice în istoria recentă a României". Descoperă (in Romanian). Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ↑ Bogdana Boga (November 8, 2007). "Basescu a pierdut procesul "tiganca imputita"". Ziare.com (in Romanian). Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- 1 2 3 Alina Mihai (May 3, 2020). "Traian Băsescu, reclamat şi el la CNCD pentru afirmaţii "incitatoare la ură". Ce a spus fostul preşedinte despre etnicii romi". Mediafax (in Romanian). Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ↑ Liberă, Europa (May 20, 2020). "CNCD: Traian Băsescu și Nicolae Bacalbașa, amendați pentru discriminare la adresa romilor". Europa Liberă România (in Romanian). Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ↑ "Romanian mayor fined over 'Roma wall'". Euronews. November 18, 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ↑ "Primarul din Baia Mare, amendat pentru că nu a demolat un zid în jurul unor blocuri de romi". Mediafax (in Romanian). January 29, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ↑ "Primarul din Târgu Mureș vrea să decidă statul cine are voie să facă copii: "Țiganii sunt o problemă serioasă a României"". Digi24 (in Romanian). January 13, 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ↑ "Cine este Sorin Lavric, liderul AUR care susține că romii sunt o "plagă socială". A fost exclus din Uniunea Scriitorilor". Pro TV (in Romanian). December 8, 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ↑ "The Situation of Roma in an Enlarged European Union" (PDF). European Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Decade in Brief". Decade of Roma Inclusion. Archived from the original on January 29, 2015.

- ↑ "INSTRUMENT FOR PRE-ACCESSION ASSISTANCE (IPA II) 2014-2020" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

- ↑ "Populatia de 10 ani si peste analfabeta dupa etnie, pe sexe si judete" (PDF) (in Romanian). Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- 1 2 Delia-Luiza Niță, ENAR Shadow Report 2008: Racism in Romania Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, European Network Against Racism

- ↑ Regele Cioabă se plânge la Guvern că rămâne fără supuşi – Gandul Archived 2010-09-13 at the Wayback Machine. Gandul.info (2007-09-10).Retrieved on 2012-01-15.

- ↑ Ioan Durnescu; Cristian Lazar; Roger Shaw (9 May 2003). "Incidence and Characteristics of Rroma Men in Romanian Prisons". The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice. 41 (3): 237–244. doi:10.1111/1468-2311.00239. S2CID 145517603.

- ↑ Ioan Durnescu (15 February 2019). "Pains of Reentry Revisited". International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 63 (8): 1482–1498. doi:10.1177/0306624X19828573. PMID 30767582. S2CID 73447392.

- ↑ Vasile Cernat (6 September 2020). "Roma undercount and the issue of undeclared ethnicity in the 2011 Romanian census". International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 24 (6): 761–766. doi:10.1080/13645579.2020.1818416. S2CID 225206490.

- ↑ Evenimentul Zilei. April 7, 2010. Evz.ro. Retrieved on 2012-01-15.

- ↑ V.M. (November 27, 2010). "Sondaj CCSB: 36% dintre romani cred ca tiganii ar putea deveni o amenintare pentru tara". Hotnews.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- 1 2 Vasile Dâncu. "Tele-vremea țiganilor" (PDF). IRES (in Romanian). Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ↑ "Sondaj IRES: 7 din 10 români nu au încredere în romi". Radio Free Europe Romania (in Romanian). Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ↑ Diana Meseșan (March 9, 2022). "REPORTAJ. Ce au pățit niște romi săraci din Ucraina când au fost confundați, în Gara de Nord, cu romi de la noi" (in Romanian). Libertatea. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ Sorin Dojan (May 30, 2022). "Refugiați romi goniți de la standul de mâncare. Problemele romilor ajunși în România din cauza războiului". Radio Free Europe Romania (in Romanian). Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- ↑ Ivana Kottasová (August 7, 2022). "'You are not a refugee.' Roma refugees fleeing war in Ukraine say they are suffering discrimination and prejudice". CNN. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- 1 2 "Recensamantul Populatiei Si Locuintelor" [Population and Housing Census]. Institutul Naţional de Statistică. 2011. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ↑ "Recensământul populației și locuințelor runda 2021- rezultate provizorii | Institutul Național de Statistică". insse.ro. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ↑ "Rezultate 2011 – Recensamantul Populatiei si Locuintelor".

- ↑ Hancock 2005, p. xx: 'While a nine century removal from India has diluted Indian biological connection to the extent that for some Romani groups, it may be hardly representative today, Sarren (1976:72) concluded that we still remain together, genetically, Asian rather than European'

- ↑ K. Meira Goldberg; Ninotchka Devorah Bennahum; Michelle Heffner Hayes (2015). Flamenco on the Global Stage: Historical, Critical and Theoretical Perspectives. McFarland. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-7864-9470-5. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Simon Broughton; Mark Ellingham; Richard Trillo (1999). World Music: Africa, Europe and the Middle East. Rough Guides. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-85828-635-8. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ "ORD DE URGENTA 57 03/07/2019 - Portal Legislativ".

- ↑ Folosirea limbii minorităților naționale (1) În unitățile/subdiviziunile administrativ-teritoriale în care cetățenii aparținând unei minorități naționale au o pondere de peste 20% din numărul locuitorilor, stabilit la ultimul recensământ, autoritățile administrației publice locale, instituțiile publice aflate în subordinea acestora, precum și serviciile publice deconcentrate asigură folosirea, în raporturile cu aceștia, și a limbii minorității naționale respective, în conformitate cu prevederile Constituției, ale prezentului cod și ale tratatelor internaționale la care România este parte.

- ↑ "Singura școală din România cu predare în limba țigănească se află în Timiș. Ce talent au copiii și de ce vin cu drag la școală". 22 February 2014.

- ↑ Cartierul Gârcini adună aproximativ 6000 persoane (înregistrate oficial, conform Biroului Județean de Administrare a Bazelor de Date), însă organizațiile locale estimează 10.000 locuitori. Locuitorii cartierului sunt considerați “țigani/romi”, însa la ultimul recensământ (2011), doar 324 persoane s-au declarat de etnie romă, restul declarându-se în mare parte români

- ↑ "Magyarul beszélő romák Erdélyben. Területi elhelyezkedés és lakóhelyi szegregáció".

- ↑ Census 2002, by religion. (PDF). insse.ro. Retrieved on 2012-01-15.

- ↑ "Regele Cioabă vs. Iulian impăratul". Maxim (in Romanian). Archived from the original on December 8, 2006.

- ↑ Recensământ 2002 Archived 2012-03-05 at the Wayback Machine. Recensamant.referinte.transindex.ro. Retrieved on 2012-01-15.

- ↑ Popan, Cosmin (June 10, 2006). "Cioabă şi oalele sparte din şatră" (in Romanian).

- ↑ "La Mânăstirea Curtea de Argeş s-au sfinţit doar podoabele specifice rromilor". Curierul Naţional (in Romanian). September 3, 2003. Archived from the original on April 29, 2019. Retrieved November 5, 2006.

External links

- Assessment for Roma in Romania Center for International Development and Conflict Management Last Updated December 31, 2003

- Come Closer. Inclusion and Exclusion of Roma in Present Day Romanian Society By Gabor Fleck, Cosima Rughinis (Eds.) 2009 ISBN 978-973-8973-09-1. Full text from Google Books