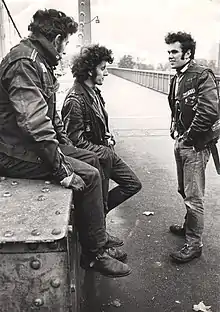

Rockers (also known as leather boys[1] or ton-up boys[2]) are members of a biker subculture that originated in the United Kingdom during the 1950s. It was mainly centred on motorcycles and rock 'n' roll music. By 1965, the term greaser had also been introduced to Great Britain[3][4][5] and, since then, the terms greaser and rocker have become synonymous within the British Isles, although used differently in North America and elsewhere. Rockers were also derisively known as Coffee Bar Cowboys.[6] Their Japanese counterpart was called the Kaminari-Zoku (Thunder Tribe/Clan/Group, or Thunderers).[7]

Origins

Until the post-war period motorcycling held a prestigious position and enjoyed a positive image in British society, being associated with wealth and glamour. Starting in the 1950s, the middle classes were able to buy inexpensive motorcars so that motorcycles became transport for the poor.[8]

The rocker subculture came about due to factors such as: the end of post-war rationing in the UK, a general rise in prosperity for working class youths, the recent availability of credit and financing for young people, the influence of American popular music and films, the construction of race track-like arterial roads around British cities, the development of transport cafes and a peak in British motorcycle engineering. The name "rocker" came not from music, but from the rockers found in 4-stroke engines, as opposed to the two stroke engines used by scooters and ridden by mods.

During the 1950s,[9] they were known as "ton-Up boys" because doing a ton is English slang for driving at a speed of 100 mph (160 km/h) or over. The rockers or ton-up boys took what was essentially a sport and turned it into a lifestyle, dropping out of mainstream society[10] and "rebelling at the points where their will crossed society's".[11] This damaged the public image of motorcycling in the UK.[8]

The mass media started targeting these socially powerless youths and cast them as "folk devils", creating a moral panic[12] through highly exaggerated and ill-founded portrayals.[13][14] From the 1960s on, due to the media fury surrounding the mods and rockers, motorcycling youths became more commonly known as rockers, a term previously little known outside small groups.[15] The public came to consider rockers as hopelessly naive, loutish, scruffy, motorized cowboys, loners or outsiders.[15]

The Rocker subculture was associated with 1950s and early-1960s rock and roll music by artists such as Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran and Chuck Berry, music that George Melly called "screw and smash" music.[14]

Café racers

The term café racer originated in the 1950s,[16] when bikers often frequented transport cafés, using them as starting and finishing points for road races. A café racer is a motorcycle that has been modified for speed and good handling rather than for comfort.[17] Features include: a single racing seat, low handlebars (such as ace bars or one-sided clip-ons mounted directly onto the front forks for control and aerodynamics), large racing petrol tanks (aluminium ones were often polished and left unpainted), swept-back exhaust pipes, rear-set footpegs (to give better clearance while cornering at high speeds) with or without half or full race fairings.[18]

These motorcycles were lean, light and handled various road surfaces well. The most defining machine of the rocker heyday was the Triton, which was a custom motorcycle made of a Norton Featherbed frame and a Triumph Bonneville engine. It used the most common and fastest racing engine combined with the best handling frame of its day.[19][20] Other popular motorcycle brands included BSA, Royal Enfield and Matchless.

The term café racers is now also used to describe motorcycle riders who prefer vintage British, Italian or Japanese motorbikes from the 1950s to late 1970s. These modern café racers do not resemble the rockers of earlier decades, and they dress in a more modern and comfortable style, with only a hint of likeness to the rocker style, nor do they share the passion for 50s rock'n'roll. These modern café racers have taken elements of the American greaser, British rocker, and modern motorcycle rider styles to create a look of their own.[21][22] Rockers in the 2000s tend still to ride classic British motorcycles, however, classically styled European café racers are now also seen, such as Moto Guzzi or Ducati, as well as classic Japanese bikes, some with British-made frames such as those made by Rickman.

Characteristics

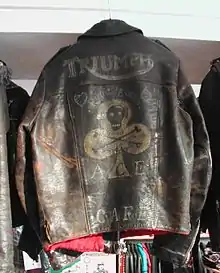

Rockers bought standard factory-made motorcycles and stripped them down, tuning them up and modifying them to appear like racing bikes. Their bikes were not merely transport, but were used as an object of intimidation and masculinity projecting them uneasily close to death,[14] an element exaggerated by their use of skull and crossbone-type symbolism.

First seen in the United States and then England,[15] the rocker fashion style was born out of necessity and practicality. Rockers wore heavily decorated leather motorcycle jackets, often adorned with metal studs, patches, pin badges and sometimes an Esso gas man trinket. When they rode their motorcycles, they usually wore no helmet, or wore a classic open-face helmet, aviator goggles and a white silk scarf (to protect them from the elements). Other common items included: T-shirts, leather caps, Levi's or Wrangler jeans,[23] leather trousers, tall motorcycle boots (often made by Lewis Leathers and Goldtop) or brothel creepers/beetle crushers. Also popular was a patch declaring membership of the 59 Club of England, a church-based youth organization that later formed into a motorcycle club with members all over the world. The rocker hairstyle, kept in place with Brylcreem, was usually a tame or exaggerated pompadour hairstyle, as was popular with some 1950s rock and roll musicians.

Largely due to their clothing styles and dirtiness, the rockers were not widely welcomed by venues such as pubs and dance halls. Rockers also transformed rock and roll dancing into a more violent, individualistic form beyond the control of dance hall management.[14] They were generally reviled by the British motorcycle industry and general enthusiasts as being as an embarrassment and bad for the industry and the sport.[24]

Originally, many rockers opposed recreational drug use, and according to Johnny Stuart:

They had no knowledge of the different sorts of drugs. To them amphetamines, cannabis, heroin were all drugs - something to be hated. Their ritual hatred of Mods and other sub-cultures was based in part on the fact that these people were believed to take drugs and were therefore regarded as sissies. Their dislike of anyone connected with drugs was intense.[25]

Cultural legacy

The rockers' look and attitude influenced pop groups in the 1960s, such as The Beatles,[9] as well as hard rock and punk rock bands and fans in the late 1970s. The look of the ton-up boy and rocker was accurately portrayed in the 1964 film The Leather Boys. The rocker subculture has also influenced the rockabilly revival and the psychobilly subculture.

Many contemporary rockers still wear engineer boots or full-length motorcycle boots, but Winklepickers (sharp pointed shoes) are no longer common. Some wear brothel creepers (originally worn by Teddy Boys), or combat boots. Rockers have continued to wear leather motorcycle jackets, often adorned with patches, studs, spikes and painted artwork; jeans or leather trousers; and white silk scarves. Leather caps adorned with metal studs and chains, common among rockers in the 1950s and 1960s, are rarely seen any more. Instead, some contemporary rockers wear a classic woollen flat cap.

Rocker reunions

In the early 1970s, the British rocker and hardcore motorcycle scene fractured and evolved under new influences coming from California: the hippies and the Hells Angels.[26] The remaining rockers became known as greasers, and the scene had all but died out.

In the early 1980s, a Rockers revival was started by Lenny Paterson and a handful of original rockers. Paterson organized rocker reunion dances called piss-ups, which attracted individuals from as far as Europe. The first rocker reunion motorcycle run of 30 classic British motorcycles rode to Battersea - home of the Chelsea Bridge Boys. Following runs went to other destinations with historic relevance to Rockers such as Brighton.

In 1994 Mark Wilsmore[27] and others organised the first Ace Cafe Reunion to mark the 25th anniversary of the closure of the famous transport cafe before going on to re-opening and establishing a series of events.[28] These events now attract up to 40,000 motorcyclists.[29][30]

Films and documentaries

- The Leather Boys

- BBC Home Truths

- Look at Life: Behind the Ton-Up Boys [31]

See also

References

- ↑ Stuart, John, Rockers! Kings of the Road (Plexus Publishing, 1996). ISBN 0-85965-125-8.

- ↑ 14 February 1961, The Daily Express (London)

- ↑ Motor Cycle, 24 June 1965. p.836. On the Four Winds by 'Nitor'. "It was, I have it on good authority, as much a surprise to the so-called rockers to find they are now "greasers" as it was to the general public...The people in question—greasy rockers?—are expected to sit back uncomplainingly while learned gentlemen in such papers as the Guardian discuss the pros and cons...I would suggest to the Guardian's correspondent, and to any other erudite commentators who feel duty bound to join in, that the subject should be allowed to die a natural death." Accessed 2014-02-20

- ↑ greaser, n. Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. (1989); online version December 2011. <http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/81098>

- ↑ The Sun newspaper wrote, "you can call rockers Greasers if you like. ... Greasers just means they have to put a lot of work into bikes."

- ↑ Frame, Pete, The Restless Generation: How Rock Music Changed the Face of 1950s Britain (Rogan House, 2007) ISBN 0-9529540-7-9.

- ↑ Bailey, Don C.A., Glossary of Japanese Neologisms (Arizona Press, 1962).

- 1 2 Suzanne McDonald-Walker, 'Bikers: Culture, Politics and Power' Berg Publishers, 2000. ISBN 1-85973-356-5

- 1 2 Mods, rockers, and the music of the British invasion. James E. Perone. Praeger, 2008. ISBN 0-275-99860-6. pp. 3, 65, etc.

- ↑ Skateboarding, Space and the City, Borden, Iain. Berg Publishers, (2003). ISBN 1-85973-493-6 p. 137

- ↑ Dancin' in the streets!: anarchists, IWWs, surrealists, Situationists, Franklin Rosemont, Charles Radcliffe. Charles H Kerr 2005 ISBN 0-88286-302-9

- ↑ Stanley Cohen; (1972). Folk Devils and Moral Panics; The Creation of the Mods and Rockers Routledge. ISBN 0-85965-125-8.

- ↑ Resistance through rituals: youth subcultures in post-war Britain By Stuart Hall, Tony Jefferson. Routledge, 1990. ISBN 0-415-09916-1

- 1 2 3 4 The sociology of youth culture and youth subcultures: Sex and drugs and rock 'n' roll by Mike Brake 1980 Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 0-7100-0364-1

- 1 2 3 Nuttall, Jeff. Bomb Culture Paladin, London 1969. pp. 27-29

- ↑ McCallum, Duncan (8 February 2014). "The return of motorcycling's cafe racers". Herald Scotland. Herald & Times Group. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

British motorcycle customisation stretches back to the 1950s, when the term cafe racer was coined. They were stripped-down machines, lighter than stock with dropped clip-on handlebars to make the riding position more aerodynamic, and were the low-cost mode of transport for the growing band of post-war rockers who would race ton-up (100mph) between transport cafes, such as the famous Ace Cafe on London's North Circular Road, along the then quiet motorway network.

- ↑ The Café Racer Phenomenon (Those were the days...), Alastair Walker. Veloce Publishing 2009. ISBN 1-84584-264-2

- ↑ Reg Everett and Mick Walker. Rocker to Racer. Breedon Books. 2010. ISBN 1-85983-679-8

- ↑ Seate, Mike. Café Racer The Motorcycle: Featherbeds, Clip-ons, Rear-sets and the Making of a Ton-up Boy. Parker House (2008). ISBN 0-9796891-9-8

- ↑ Welte, Sabine, Cafe Racer. Bruckmann Verlag GmbH, 2008. ISBN 3-7654-7694-3

- ↑ Clay, Mike. (1988) Cafe Racers: Rockers, Rock 'n' Roll and the Coffee-bar Cult. London: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0-85045-677-0

- ↑ Café racers of the 1960s: machines, riders and lifestyle, Mick Walker. Crowood (1994)

- ↑ Jeans: A Cultural History of an American Icon, James Sullivan, Gotham, 2006. ISBN 1-59240-214-3

- ↑ The Bsa Gold Star, Mick Walker. Redline Books, 2004 ISBN 0-9544357-3-7

- ↑ Rockers! Kings of the Road by John Stuart, Plexus Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-85965-125-8

- ↑ Cookson, Brian (2006), Crossing the River, Edinburgh: Mainstream, ISBN 1-84018-976-2, OCLC 63400905

- ↑ Cycle World: The Ace Café. Riding the Reunion

- ↑ Missy D. Interview mit Mark Wilsmore Ace Café, London (deutsche Übersetzung). Speeding E-magazine, July 2007

- ↑ Brighton and Hove City Council. Ace Cafe Reunion, Madeira Drive (scroll down page) Retrieved 2014-01-26

- ↑ Motorcycle News (MCN), UK. September 17, 2008

- ↑ Writer: Driscoll, Frank. Rank Organisation Special Features Division, 1964.

Bibliography

- Stanley Cohen; (1972). Folk Devils and Moral Panics; The Creation of the Mods and Rockers. Routledge. ISBN 0-85965-125-8.

- Johnny Stuart; (1987). Rockers!. Plexus Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-85965-125-8

- Danny Lyons; (2003). The Bikeriders. Wild Palms 1968, Chronicle Books ISBN 0-8118-4160-X

- Winston Ramsey; (2002). The Ace Cafe then and now. After the Battle, ISBN 1870067436

- Ted Polhemus; (1994). Street Style. Thames and Hudson / V&A museum ISBN 0-500-27794-X

- Steve Wilson; (2000). Down the Road. Haynes ISBN 1-85960-651-2

- Alastair Walker; (2009) The Café Racer Phenomenon. Veloce Publishing ISBN 978-1-84584-264-2

- Horst A. Friedrichs (2010): Or Glory: 21st Century Rockers. Prestel ISBN 978-3-7913-4469-0

External links

- The 59 Club: London's outlaws article on Visor Down