Rikuzentakata

陸前高田市 | |

|---|---|

City | |

New Rikuzentakata City Hall | |

Flag  Seal | |

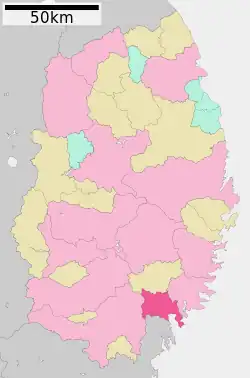

Location of Rikuzentakata in Iwate Prefecture | |

Rikuzentakata | |

| Coordinates: 39°01′40.9″N 141°37′31.5″E / 39.028028°N 141.625417°E | |

| Country | Japan |

| Region | Tōhoku |

| Prefecture | Iwate |

| Government | |

| • -Mayor | Toba Futoshi |

| Area | |

| • Total | 231.94 km2 (89.55 sq mi) |

| Population (October 10, 2020) | |

| • Total | 18,262 |

| • Density | 79/km2 (200/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Japan Standard Time) |

| Phone number | 0192-54-2111 |

| Climate | Cfa |

| Website | Official website |

| Symbols | |

| Bird | Common gull |

| Flower | Camellia |

| Tree | Cryptomeria |

Rikuzentakata (陸前高田市, Rikuzentakata-shi) is a city located in Iwate Prefecture, Japan. In the census of 2010, the city had a population of 23,302 (2005: 24,709),[1] and a population density of 100 persons per km². The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami caused extensive damage to the city. As of 31 March 2020, the city had an estimated population of 19,062, and a population density of 82 persons per km² in 7,593 households.[2] The total area of the city is 231.94 square kilometres (89.55 sq mi).[3]

Geography

Rikuzentakata is located in the far southeast corner of Iwate Prefecture, bordered by the Pacific Ocean to the east. The city contained Lake Furukawanuma until the 2011 tsunami destroyed it. Parts of the coastal area of the city are within the borders of the Sanriku Fukkō National Park.

Neighboring municipalities

Iwate Prefecture

Miyagi Prefecture

Climate

Rikuzentakata has a humid climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) bordering on an oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb) with warm summers and cold winters. The average annual temperature is 11.1 °C (52.0 °F). The average annual rainfall is 1,343 millimetres (52.9 in), with September as the wettest month and January as the driest month. The temperatures are highest on average in August, at around 23.7 °C (74.7 °F), and lowest in January, at around 0.0 °C (32.0 °F).[4]

| Climate data for Rikuzentakata (2011−2020 normals, extremes 2011−present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.8 (55.0) |

17.6 (63.7) |

23.5 (74.3) |

29.4 (84.9) |

34.4 (93.9) |

32.8 (91.0) |

36.8 (98.2) |

36.0 (96.8) |

32.2 (90.0) |

28.0 (82.4) |

21.4 (70.5) |

18.5 (65.3) |

36.8 (98.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

5.2 (41.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

20.1 (68.2) |

22.4 (72.3) |

25.9 (78.6) |

27.9 (82.2) |

24.9 (76.8) |

19.2 (66.6) |

13.2 (55.8) |

6.7 (44.1) |

16.2 (61.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.4 (32.7) |

0.8 (33.4) |

4.7 (40.5) |

9.3 (48.7) |

14.8 (58.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

21.9 (71.4) |

23.7 (74.7) |

20.3 (68.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

8.1 (46.6) |

2.6 (36.7) |

11.6 (52.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.0 (26.6) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

0.1 (32.2) |

4.4 (39.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

14.5 (58.1) |

19.0 (66.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

9.8 (49.6) |

3.7 (38.7) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

7.7 (45.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.6 (12.9) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

0.7 (33.3) |

7.2 (45.0) |

14.3 (57.7) |

12.7 (54.9) |

7.4 (45.3) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 33.3 (1.31) |

34.3 (1.35) |

98.2 (3.87) |

123.7 (4.87) |

113.3 (4.46) |

137.9 (5.43) |

170.5 (6.71) |

167.1 (6.58) |

180.3 (7.10) |

161.0 (6.34) |

69.1 (2.72) |

51.5 (2.03) |

1,350.9 (53.19) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 4.8 | 5.4 | 7.0 | 8.3 | 9.2 | 10.2 | 12.6 | 12.6 | 11.1 | 8.7 | 6.4 | 6.6 | 102.9 |

| Source: JMA[5][6] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Per Japanese census data,[7] the population of Rikuzentakata peaked in the 1950s and has declined steadily over the past 70 years.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 20,773 | — |

| 1930 | 24,494 | +17.9% |

| 1940 | 26,222 | +7.1% |

| 1950 | 32,609 | +24.4% |

| 1960 | 31,839 | −2.4% |

| 1970 | 30,308 | −4.8% |

| 1980 | 29,356 | −3.1% |

| 1990 | 27,242 | −7.2% |

| 2000 | 25,676 | −5.7% |

| 2010 | 23,302 | −9.2% |

| 2020 | 18,262 | −21.6% |

History

The area of present-day Rikuzentakata was part of ancient Mutsu Province, and has been settled since at least the Jōmon period. The area was inhabited by the Emishi people, and came under the control of the Yamato dynasty during the early Heian period. During the Sengoku period, the area was dominated by various samurai clans before coming under the control of the Date clan during the Edo period, who ruled Sendai Domain under the Tokugawa shogunate.

The towns of Kesen and Takata were established within Kesen District on April 1, 1889 with the establishment of the modern municipality system. The area was devastated by the 1896 Sanriku earthquake and the 1933 Sanriku earthquake. Kesen and Takata merged with the neighboring town of Hirota and villages of Otomo, Takekoma, Yokota and Yonezaki on January 1, 1955 to form the city of Rikuzentakata.

2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami

Rikuzentakata was almost completely destroyed by the tsunami following the Tōhoku earthquake. According to the police, every building smaller than three stories high was completely flooded,[8] with buildings bigger than three stories high being flooded partially, one of the buildings being the city hall, where the water also reached as high as the third floor.[9] The Japan Self-Defense Forces initially reported that between 300 and 400 bodies were found in the town.[10] On 14 March, an illustrated BBC report showed a picture of the town, describing it as "almost completely flattened."[11] The town's tsunami shelters were designed for a wave of three to four metres (9.8 to 13.1 ft) in height, but the tsunami of March 2011 created a wave 13 metres (43 ft) high which inundated the designated safe locations.[12] Local officials estimated that 20% to 40% of the town's population has been killed.[13] Although the town was prepared for earthquakes and tsunamis and had a 6.5-metre-high (21 ft) seawall, it was not enough and more than 80% of 8,000 houses were swept away.[14]

A BBC film dated 20 March reported that the harbour gates of the town failed to shut as the tsunami approached, and that 45 young firemen were swept away while attempting to close them manually. The same film reported that 500 bodies had been recovered in the town, but that 10,000 people were still unaccounted-for out of a population of 26,000.[15] As of 3 April 2011, 1,000 people from the town were confirmed dead with 1,300 still missing.[16] In late May 2011, an Australian reporter interviewed a surviving volunteer firefighter who said 49 firefighters were killed in Rikuzentakata by the tsunami, among 284 firefighters known to have died along the affected coast, many while closing the doors of the tsunami barriers along the seashore.[17]

Sixty-eight city officials, about one-third of the city's municipal employees, were killed. The town's mayor, Futoshi Toba, was at his post at the city hall and survived, but his wife was killed at their seaside home.[18] The wave severely damaged the artifact and botanical collection at the city's museum and killed all six staff.[19][20] The final death toll was 1,656 killed and 223 missing and presumed dead. Portions of the city subsided by over a meter.

As a countermeasure against future tsunami, Rikuzentakata's city centre was elevated upon rock fill in a megaproject. In 2014, a massive conveyor belt system was being used to carry rock from a hill across the Kesen River from the city centre. The conveyor belt system featured a long suspension span that crossed the Kesen River, and was named the "Bridge of Hope." The project elevated the city centre by more than 10 metres (33 ft).[21]

Currently a new marketplace and community center has been established upon one such elevated plot of land, and work is ongoing to create a new street grid. In addition, new bridges are being established across the Kesen River, including an extension and bypass for the Sanriku Expressway and Japan National Route 45. The location of the rock quarry for the reconstruction megaproject is being developed as a new neighborhood.

Government

Rikuzentakata has a mayor-council form of government with a directly elected mayor and a unicameral city legislature of 18 members. Rikuzentaka, together with the town of Sumita together contributes one seat to the Iwate Prefectural legislature. In terms of national politics, the city is part of Iwate 2nd district of the lower house of the Diet of Japan.

Economy

The local economy of Rikuzentakata is based heavily on commercial fishing and food processing. As of 2011, oyster farming produced ¥40 million in annual sales for the city.[22]

Education

Rikuzentakata has eight public elementary schools and two public junior high schools operated by the city government, and one public high school operated by the Iwate Prefectural Board of Education.[23][24] There is also one private high school.

Transportation

Railway

![]() East Japan Railway Company (JR East) - Ōfunato Line (services suspended indefinitely and replaced by a BRT)

East Japan Railway Company (JR East) - Ōfunato Line (services suspended indefinitely and replaced by a BRT)

Highway

Local attractions

Takata-matsubara

Takata-matsubara (高田松原) was a two-kilometre stretch of shoreline that was lined with approximately seventy thousand pines.[25] In 1927 it was selected as one of the 100 Landscapes of Japan (Shōwa era) and in 1940 it was designated a Place of Scenic Beauty.[26][27] After the 2011 tsunami a single, ten-metre, two-hundred-year-old tree remained from the forest. Due to land subsidence and coastal erosion this was only five metres from the sea and was at threat from increased salinity. The Association for the Protection of Takata-Matsubara along with the municipal and prefectural governments took measures, including the erection of barriers, to protect the surviving pine.[25]

As of September 2011, there were signs that these measures had failed, and that the tree was dead due to salt water poisoning.[28] In September 2012, the tree was felled for preservation and replaced in 2013 with an artificial "commemorative tree".[29]

Notable people from Rikuzentakata

- Naoya Hatakeyama, photographer

- Toru Kikawada, politician

- Hiroaki Murakami, actor

- Rōki Sasaki, baseball player

Twin towns – sister cities

Rikuzentakata is twinned with:[30]

Crescent City, United States (2018)

Crescent City, United States (2018)

References

- ↑ "2010 census". Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ↑ Rikuzentakata city official statistics(in Japanese)

- ↑ 詳細データ 岩手県紫波町. 市町村の姿 グラフと統計でみる農林水産業 (in Japanese). Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ↑ "Climate Rikuzen Takata: Temperature, Climograph, Climate table for Rikuzen Takata - Climate-Data.org". en.climate-data.org.

- ↑ 観測史上1~10位の値(年間を通じての値). JMA. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ↑ 気象庁 / 平年値(年・月ごとの値). JMA. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ↑ "Iwate / 岩手県 (Japan): Prefecture, Cities, Towns and Villages - Population Statistics, Charts and Map". www.citypopulation.de.

- ↑ "Honderden doden in Japanse kuststad (Hundreds dead in Japanese coastal town)" (in Dutch). www.rtlnieuws.nl, Retrieved 12 March 2011

- ↑ Kyodo News, "Deaths, people missing set to top 1,600: Edano", Japan Times, 13 March 2011.

- ↑ "Japan army says 300-400 bodies found in Rikuzentakata: Report". Archived from the original on April 7, 2011. Retrieved March 13, 2011. Japan army says 300-400 bodies found in Rikuzentakata: Report

- ↑ https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-12729784 Picture 6 of the series

- ↑ http://www3.nhk.or.jp/daily/english/28_04.html NHK News Report says March 11th tsunami confirmed up to 13 meters high, 28 March 2011

- ↑ Tsunami preparation leads citizens into low-lying death traps.https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/asia-pacific/tsunami-preparation-leads-citizens-into-low-lying-death-traps/article1943381/

- ↑ ShelterBox Response Team operational in Iwate Prefecture News update from charity ShelterBox, 22 March 2011

- ↑ The floodgate that didn't work to stop the tsunami.https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-pacific-12801085

- ↑ Ito, Shingo (Agence France-Presse/Jiji Press), "Iwate pine that withstood the wage now symbol of hope", Japan Times, 3 April 2011, p. 3.

- ↑ Video shows terror as killer waves hit, Mark Willacy, ABC News Online, 31 May 2011

- ↑ Agence France-Presse/Jiji Press, "Mayor perseveres amid his loss", Japan Times, 13 April 2011, p. 3. Toba's two children were at school and survived.

- ↑ Corkill, Edan (8 June 2011). "Tsunami-struck museum starts recovering collection" – via Japan Times Online.

- ↑ "After the Tsunami: Rescuing Relics of Rikuzentakata's History and Culture". nippon.com. 11 March 2015.

- ↑ , "Sanriku Coast Travel", Japan Guide, 27 August 2014.

- ↑ Matsuyama, Kanoko, and Stuart Biggs, (Bloomberg L.P.), "Tsunami - insult to injury", Japan Times, 30 April 2011, p. 3.

- ↑ "小・中学校一覧". www.city.rikuzentakata.iwate.jp.

- ↑ "陸前高田市立気仙中学校". www.edu.city-rikuzentakata.iwate.jp.

- 1 2 Asami, Toru (18 April 2011). "Battle to protect sole surviving pine tree". Daily Yomiuri. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ↑ "日本八景(昭和2年)の選定内容" (PDF). Ministry of the Environment. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ "Database of Nationally-Designated Cultural Properties etc". Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ↑ YAMANISHI, ATSUSHI (14 September 2011). "Lone pine tree that is symbol of hope in disaster area fights for survival". Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ↑ "Rikuzentakata's lone pine tree to return as symbol of remembrance of 3/11". Asahi Shimbun. 13 September 2012. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ↑ "December 17, 2018 Council Agenda" (PDF). crescentcity.org. City of Crescent City. 2018-12-17. pp. 6–7 (10–11). Retrieved 2021-08-08.

External links

![]() Media related to Rikuzentakata, Iwate at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rikuzentakata, Iwate at Wikimedia Commons