| Rhinocarcinosoma Temporal range: Late Silurian, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossil carapace and portions of the abdomen of R. vaningeni | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Order: | †Eurypterida |

| Superfamily: | †Carcinosomatoidea |

| Family: | †Carcinosomatidae |

| Genus: | †Rhinocarcinosoma Novojilov, 1962 |

| Type species | |

| †Rhinocarcinosoma vaningeni (Clarke & Ruedemann, 1912) | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Rhinocarcinosoma is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Rhinocarcinosoma have been discovered in deposits ranging of Late Silurian age in the United States, Canada and Vietnam. The genus contains three species, the American R. cicerops and R. vaningeni and the Vietnamese R. dosonensis. The generic name is derived from the related genus Carcinosoma, and the Greek ῥινός (rhinós, "nose"), referring to the unusual shovel-shaped protrusion on the front of the carapace (head plate) of Rhinocarcinosoma, its most distinctive feature.

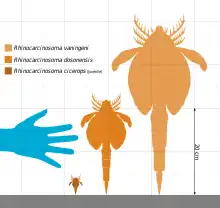

Other than the protrusion, Rhinocarcinosoma was anatomically very similar to its close relative, Eusarcana, though it lacked the scorpion-like telson (the posteriormost division of the body) of that genus. Further distinguishing features include more slender appendages and slightly different ornamentation of scales. In terms of size, Rhinocarcinosoma was a medium-sized carcinosomatid eurypterid, with the largest species, R. vaningeni, reaching lengths of 39 centimetres (15.4 in). In contrast to other carcinosomatids, Rhinocarcinosoma is not known only from marine settings, but also from deposits that were once lakes or rivers. It was adapted to a bottom-dwelling lifestyle, as either a burrowing or digging scavenger or top predator, feeding on other invertebrates and small fish.

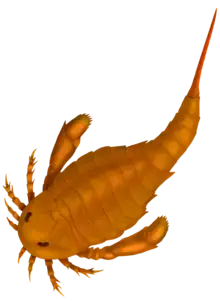

Description

Rhinocarcinosoma was a medium-sized carcinosomatid eurypterid, with the largest species, R. vaningeni, reaching lengths of 39 centimetres (15.4 in) and the second largest, R. dosonensis, reaching lengths of 22 centimetres (8.7 in).[1] In terms of the outline of the body, with a broad abdomen and a nearly tubular postabdomen (tail), Rhinocarcinosoma was similar to the related genus Eusarcana.[2][3] Its appendages, large and with spines, are also similar to those of Eusarcana,[3] though the more anterior (forwards) appendages of Rhinocarcinosoma were more slender than those of Eusarcana.[4] Although historically assumed to have had a scorpion-like telson (the posteriormost division of the body), like Eusarcana,[3][2] more complete fossils of R. dosonensis revealed that this was not the case, although the telson did slightly curve upwards.[4] Like Eusarcana, Rhinocarcinosoma possessed an ornamentation of scales on its carapace (head plate), though the scales of Rhinocarcinosoma were smaller and more closely arranged.[3] The type A genital appendage (female reproductive organ) of Rhinocarcinosoma was broader and more rounded than that of Eusarcana.[4]

The most distinctive feature of Rhinocarcinosoma was the shovel-shaped protrusion developed from the most forward-facing portion of the carapace.[5] It is possible that the snout was used for digging purposes.[3] As of yet, this feature is only confidently known from R. vaningeni, given that the relevant portion of the carapace has not been preserved in adult fossils of R. dosonensis[4] and R. cicerops (which lacks known adult fossils altogether).[3]

All species of Rhinocarcinosoma also share certain other features of the carapace, including the carapace being more or less subtriangular in shape, with a width to length ratio of about 3:2, and the ocellar mound (the raised surface where the ocelli, smaller eyes, were located) being placed centrally and being the highest point of the carapace.[3][4] The species R. cicerops shares the forward and prominent position of the ocelli with R. vaningeni, but only has a slight development of the snout compared to the others.[3] Its fossils are also the smallest of any species, at only 4 centimetres (1.6 in) in length,[1] but all known fossil specimens of R. cicerops are of immature individuals, meaning that it is possible that the adults were even more similar to R. vaningeni.[3] Although formal synonymisation has never been conducted, it is possible that R. cicerops were actually juvenile R. vaningeni.[3][4]

History of research

Rhinocarcinosoma fossils were first found in the Illion Shale of New York State in the United States, and they were first described and discussed in detail in John Mason Clarke's and Rudolf Ruedemann's 1912 The Eurypterida of New York.[5] The earliest described species of Rhinocarcinosoma was R. cicerops, described by Clarke in 1907 as Eurypterus? cicerops. The species was described based on a single carapace discovered in the Shawangunk grit at Otisville, New York,[3] of Llandovery-Ludlow age[1] (dating not entirely certain but likely only Late Silurian, i.e. Ludlow).[4] Though the specimen was immature, Clarke considered the fossil so unusual, in that the compound eyes were so developed and the ocellar mound was fully developed despite the specimen being immature, that he named a new species.[3]

Clarke and Ruedemann referred Clarke's species to the genus Eusarcus (now known as Eusarcana) in 1912, designating it as Eusarcus (?) cicerops. Accompanying the reclassification were the assignment of several more fossils of varying sizes to the species. The reclassification to Eusarcus, although provisional, was based on the head and abdomen of E?. cicerops resembling species of that genus, in particular in the width of the body, the sub-triangular outline of the carapace and the oval shape and more or less marginal position of the eyes.[3]

The species R. vaningeni was also described by Clarke and Ruedemann in The Eurypterida of New York, like R. cicerops designated as a species of Eusarcus (as Eusarcus vaningeni). Regarded by Clarke and Ruedemann as "very unexpected and peculiar" and "puzzling", E. vaningeni was described based on fossils from Oriskany Creek in Oneida County, New York,[3] of Ludlow age.[1] Although Clarke and Ruedemann considered E. vaningeni to be undoubtedly similar to Eusarcus scorpionis (the generic type species) in general, the position of the ocelli between the eyes and the large shovel-like projection in the front represented considerable differences from the type material. The snout also being developed in R. cicerops, though not to the same degree, as well as the position of the ocelli being similar, was noted by Clarke and Ruedemann as similarities between the two species.[3] E. vaningeni and E. cicerops were ultimately placed in their own genus, Rhinocarcinosoma, by Nestor Ivanovich Novozhilov in 1962, based on the placement of the eyes, the shape of the carapace and the protrusion at the front of the carapace.[4] The genus name derives from the related genus Carcinosoma and the Greek ῥινός (rhinós, "nose").[6]

The holotype specimen of R. dosonensis was discovered in a quarry in 1989 on the Ngọc Xuyên hill on the Dô Son Peninsula in northern Vietnam, part of the Dô Son Formation. Initially believed to be the remains of a chasmataspidid, it was recognised as probably being a carcinosomatid fossil in 1993.[4] Further fossils of R. dosonensis were discovered in November 1993[2] at two quarries on the Ngọc Xuyên hill.[4] Though no new species was named at the time, the eurypterid fossils could quickly be identified as belonging to Rhinocarcinosoma.[2] The new species R. dosonensis, named after the Dô Son Peninsula, was described in 2002 based on the Vietnamese fossils. Although the Vietnamese fossils did not preserve the diagnostic feature of Rhinocarcinosoma, the shovel-shaped protrusion at the front of the carapace (although some juvenile specimens preserve a slight protrusion), they could be referred to Rhinocarcinosoma on account of the rounded type A genital appendage, the triangular shape of the carapace and the slender shape of the more anterior appendages. The fossil material of R. dosonensis is the most complete of any species of Rhinocarcinosoma. The new species R. dosonensis was created for the fossils given that they differed from both R. cicerops and R. vaningeni. A juvenile specimen of R. dosonensis, of about the same size as specimens of R. cicerops, has a markedly different carapace shape and whereas the metastoma (a plate on the underside of the abdomen) of R. vaningeni expands in size anteriorly, it stays about the same size in R. dosonensis.[4]

Though Rhinocarcinosoma is a very rare genus of eurypterids,[2][3][4][5] specimens have also been found elsewhere, though they have not been assigned to any particular species. In 1985, Brian Jones and Erik N. Kjellesvig-Waering referred a poorly preserved part of a prosoma recovered in the Leopold Formation on Somerset Island in Canada to Rhinocarcinosoma sp. indet.,[7] an assignment which has been maintained as correct in later research.[8] In 1992, Samuel J. Ciurca reported a Rhinocarcinosoma specimen, a carapace, from the McKenzie Formation just east of Lock Haven, Pennsylvania.[5]

Classification

Rhinocarcinosoma is classified as part of the family Carcinosomatidae, a family within the superfamily Carcinosomatoidea, alongside the genera Carcinosoma, Eocarcinosoma, Eusarcana[9] and possibly Holmipterus.[10] The first cladogram below is adapted from a larger cladogram (simplified to only display the Carcinosomatoidea) in a 2007 study by eurypterid researcher O. Erik Tetlie, which was in turn based on results from various phylogenetic analyses on eurypterids conducted between 2004 and 2007.[11] The second cladogram below is simplified from a study by Lamsdell et al. (2015).[10]

|

Tetlie (2007)

|

Lamsdell et al. (2015)

|

Palaeoecology

Carcinosomatid eurypterids such as Rhinocarcinosoma were among the most marine eurypterids,[2] known from deposits that were once reefs, some in lagoonal settings,[5] and deeper waters.[12] In contrast to other carcinosomatids, Rhinocarcinosoma fossils are also known from non-marine environments, such as fluvial (river) and lacustrine (lake) settings.[2] The shovel-like development in the front of the carapace of Rhinocarcinosoma suggests a "mud-grubbing"[2][3] and bottom-dwelling[2] lifestyle. More evidence for Rhinocarcinosoma being a bottom-dwelling genus comes in the form of its swimming paddles being reduced in size compared to those of its relatives, such as Carcinosoma. It is likely that Rhinocarcinosoma was either a top predator, actively digging for prey or burrowing and lying in wait, or a scavenger, digging for scraps, in its environment. Given its size, it is possible that Rhinocarcinosoma fed on worms, other arthropods, lingulids and small fish. Rhinocarcinosoma would most likely have fed through using its spined forward-facing appendages to push food into its mouth.[2]

The deposits at Otisville where R. cicerops have been discovered have also yielded other eurypterids, including Hughmilleria shawangunk, Nanahughmilleria clarkei, Ruedemannipterus stylonuroides, Erettopterus globiceps, Hardieopterus myops, Kiaeropterus otisius and Ctenopterus cestrotus. Also present were early jawed fish of the genus Vernonaspis. The environment in which R. cicerops lived was a marginal marine one (influenced by both salt and fresh water, such as a lagoon or delta).[13] The eurypterid-bearing deposits of Oneida County, which yielded the fossils of R. vaningeni, have also yielded other eurypterids, such as Eurypterus remipes.[3]

The Dô Son Formation, where R. dosonensis was discovered, very rarely preserves fossils meaning that dating the deposits is difficult. In what is presumably the lower member of the formation, fossils have been found of fishes Bothriolepis and Vietnamaspis and plants Colpodexylon and Lepidodendropsis. These fossils suggest a Givetian-Frasnian (Middle to Late Devonian) age. The presumed middle member of the formation, which has yielded the eurypterid fossils, also preserves brachiopod fossils (Lingula), bivalves (Ptychoparia and Modiolopsis) and fish remains.[4] In addition to R. dosonensis, some fragmentary eurypterid fossils of the genus Hughmilleria are also known from the sites.[2][4] Because the rock layers are relatively homogenous, researchers first assumed that the entire formation was Givetian-Frasnian in age. However, it is now believed that the eurypterid-bearing deposits are of Late Silurian age given that Rhinocarcinosoma is otherwise exclusively known from Late Silurian deposits (though it is not impossible for the genus to have survived unnoticed until the Late Devonian), fish remains from the same layer are similar to Late Silurian fish and palynological samples collected suggest a Late Silurian age.[4] As the deposits have not been precisely dated, R. dosonensis and the fauna it co-occurred with have not been dated to a more precise timespan than 'Late Silurian'.[1][9][12] The sedimentology of the fossil deposits containing R. dosonensis suggest that the environment was a river delta in an otherwise semi-arid environment.[4]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lamsdell, James C.; Braddy, Simon J. (2009). "Cope's rule and Romer's theory: patterns of diversity and gigantism in eurypterids and Palaeozoic vertebrates". Biology Letters. 6 (2): 265–9. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0700. PMC 2865068. PMID 19828493. Supplemental material.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Thanh, Tống Duy; Janvier, P.; Truong, Đoàn Nhật; Braddy, Simon (1994). "New vertebrate remains associated with Eurypterids from the Devonian Do Son Formation Vietnam". Journal of Geology. 3–4: 1–11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Clarke, John M.; Ruedemann, Rudolf (1912). The Eurypterida of New York. University of California Libraries. ISBN 978-1125460221.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Braddy, Simon J.; Selden, Paul A.; Truong, Doan Nhat (2002). "A New Carcinosomatid Eurypterid From The Upper Silurian Of Northern Vietnam". Palaeontology. 45 (5): 897–915. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00267. hdl:1808/8358. ISSN 1475-4983. S2CID 129450304.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ciurca, Samuel J. (1992). "New occurrences of Silurian eurypterids (Carcinosomatidae) in Pennsylvania, Ohio and New York". The Paleontological Society Special Publications. 6: 57. doi:10.1017/S2475262200006171. ISSN 2475-2622.

- ↑ Meaning of rhino- at www.dictionary.com. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ↑ Jones, Brian; Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N. (1985). "Upper Silurian Eurypterids from the Leopold Formation, Somerset Island, Arctic Canada". Journal of Paleontology. 59 (2): 411–417. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1305035.

- ↑ Braddy, Simon J.; Dunlop, Jason A. (2000). "Early Devonian eurypterids from the Northwest Territories of Arctic Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 37 (8): 1167–1175. doi:10.1139/e00-023. ISSN 0008-4077.

- 1 2 Dunlop, J. A.; Penney, D.; Jekel, D. (2015). "A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives (version 16.0)" (PDF). World Spider Catalog.

- 1 2 Lamsdell, James C.; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Liu, Huaibao; Witzke, Brian J.; McKay, Robert M. (September 1, 2015). "The oldest described eurypterid: a giant Middle Ordovician (Darriwilian) megalograptid from the Winneshiek Lagerstätte of Iowa". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 15: 169. doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0443-9. PMC 4556007. PMID 26324341.

- ↑ Tetlie, O. Erik (2007). "Distribution and dispersal history of Eurypterida (Chelicerata)" (PDF). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 252 (3–4): 557–574. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18.

- 1 2 Tetlie, O. Erik (2007-09-03). "Distribution and dispersal history of Eurypterida (Chelicerata)". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 252 (3–4): 557–574. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.011. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ↑ "Otisville eurypterids (Silurian to of the United States)". The Paleobiology Database. Retrieved 27 July 2021.