| Part of a series on |

| Rhetoric |

|---|

|

The rhetorical situation is an event that consists of an issue, an audience, and a set of constraints. A rhetorical situation arises from a given context or exigence. An article by Lloyd Bitzer introduced the model of the rhetorical situation in 1968, which was later challenged and modified by Richard E. Vatz (1973) and Scott Consigny (1974). More recent scholarship has further redefined the model to include more expansive views of rhetorical operations and ecologies.[1][2]

Theoretical development

In the twentieth century, three influential texts concerning the rhetorical situation were published: Lloyd Bitzer's "The Rhetorical Situation," Richard E. Vatz's "The Myth of the Rhetorical Situation," and Scott Consigny's "Rhetoric and Its Situations." Bitzer argues that a situation determines and brings about rhetoric; Vatz proposes that rhetoric creates "situations" by making issues salient; and Consigny explores the rhetor as an artist of rhetoric, creating salience through a knowledge of commonplaces.

Bitzer's definition

Lloyd Bitzer began the conversation in his 1968 piece titled "The Rhetorical Situation." Bitzer wrote that rhetorical discourse is called into existence by situation. He defined the rhetorical situation as "a complex of persons, events, objects, and relations presenting an actual or potential exigence which can be completely or partially removed if discourse, introduced into the situation, can so constrain human decision or action as to bring about the significant modification of the exigence."[3] With any rhetorical discourse, a prior rhetorical situation exists. The rhetorical situation dictates the significant physical and verbal responses as well as the sorts of observations to be made. An example of this would be an activist speaking out on climate change as an apparent global problem. The situation, thus, calls for the activist to use and respond with rhetorical discourse on the climate change issue. In other words, rhetorical meaning is brought about by events. Bitzer especially focuses on the sense of timing (kairos) needed to speak about a situation in a way that can best remedy the exigence.

Three constituent parts make up any rhetorical situation.

- The first constituent part is the exigence, or a problem existing in the world. Exigence is rhetorical when it can be affected and changed by human interaction, and when it is capable of positive modification through the act of persuasion. A rhetorical exigence may be strong, unique, or important, or it may be weak, common, or trivial.

- The second constituent part is audience. Rhetorical discourse promotes change through influencing an audience's decision and actions.

- The third constituent part is the set of constraints. Constraints may be the persons, events, objects, and relations that limit decisions and action. Theorists influenced by Marx would additionally discuss ideological constraints, which produce unconscious limitations for subjects in society, including the social constraints of gender, class, and race. The speaker brings about a new set of constraints through the image of his or her personal character (ethos), logical proofs (logos), and use of emotion (pathos).[3]

Critical responses

Vatz's challenge

An important critique of Bitzer's theory came in 1973 from Richard E. Vatz. Vatz believes that rhetoric defines a situation, because the context and choices of events could be forever described, but the persuader or influencer or rhetor must select which events to make part of the agenda. Choosing certain events and not others, and deciding their relative value or importance, creates a certain presence, or salience. Vatz quotes Chaïm Perelman: "By the very fact of selecting certain elements and presenting them to the audience, their importance and pertinency to the discussion are implied. Indeed such a choice endows these elements with a presence…" [4]

In essence, Vatz claims that the definitive elements of rhetorical efforts are the struggle to create for a chosen audience saliences or agendas, and this creation is then followed by the struggle to infuse the selected situation or facts with meaning or significance. What are we persuaded to talk about? What are we persuaded it means or signifies? These questions are the relevant ones to understand persuasion, not - What does the situation make us talk about? or, What does it intrinsically mean? Situations that do not physically make us attend to them are avoided and reflect the significance of subjectivity in framing socio-political realities. Vatz believes that situations are created, for example, when an activist sets an agenda to focus on climate change, thus creating a "rhetorical situation" (a situation determined by rhetoric). The activist (rhetor) enjoys more agency because s/he is not "controlled" by a situation, but creates the situation by making it salient in language. Vatz emphasizes the social construction of the situation as opposed to Bitzer's realism or objectivism.

While the two opinions have been widely recognized, Vatz has acknowledged that his piece is less recognized than Bitzer's. Vatz admits, while claiming that audience acceptance is not dispositive for measuring validity or predictive for future audience acceptance, that "more articles and professionals in our field cite his situational perspective than my rhetorical perspective."[5] Bitzer's objectivism is clear, and easily taught as a method, despite Vatz's criticism. Vatz claims that portraying rhetoric as situation-based vitiates rhetoric as an important field, while portraying rhetoric as the cause of what people see as pressing situations enhances its significance as a field of study.

Consigny's challenge

Another response to Bitzer and Vatz came from Scott Consigny. Consigny believes that Bitzer's theory gives a rhetorical situation proper particularities, but "misconstrues the situation as being thereby determinate and determining,"[6] and that Vatz's theory gives the rhetor a correct character but does not correctly account for limits of a rhetor's ability.

Instead, he proposes the idea of rhetoric as an art. Consigny argues that rhetoric gives the means by which a rhetor can engage with a situation by meeting two conditions.

- The first condition is integrity. Consigny argues that the rhetor must possess multiple opinions with the ability to solve problems through those opinions.

- The second condition is receptivity. Consigny argues that the rhetor cannot create problems at will, but becomes engaged with particular situations.

Consigny finds that rhetoric which meets the two conditions should be interpreted as an art of topics or commonplaces. Taking after classical rhetoricians, he explains the topic as an instrument and a situation for the rhetor, allowing the rhetor to engage creatively with the situation. As a challenge to both Bitzer and Vatz, Consigny claims that Bitzer has a one-dimensional theory by dismissing the notion of topic as instrument, and that Vatz wrongly allows the rhetor to create problems willfully while ignoring the topic as situation. The intersection of topic as instrument and topic as realm gives the situation both meaning (as a perceptive formal device) and context (as material significance). Consigny concludes:

The real question in rhetorical theory is not whether the situation or the rhetor is "dominant," but the extent, in each case, to which the rhetor can discover and control indeterminate matter, using his art of topics to make sense of what would otherwise remain simply absurd.[6]

Other critical responses

Flower and Hayes

In their 1980 article, "The Cognition of Discovery: Defining a Rhetorical Problem," Linda Flower and John R. Hayes expand upon Bitzer's definition of the rhetorical situation. In studying the cognitive processes that induce discovery, Flower and Hayes propose the model of the rhetorical problem. The rhetorical problem consists of two elements: the rhetorical situation (exigence and audience), and the writer's goals involving the reader, persona, meaning, and text.[7] The rhetorical problem model explains how a writer responds to and negotiates a rhetorical situation while addressing and representing his or her goals for a given text.

Biesecker

In response to both Bitzer and Vatz, Barbara Biesecker challenges the idea of the rhetorical situation in her 1989 article "Rethinking the Rhetorical Situation from Within the Thematic of Différance."[8] Biesecker critiques both Bitzer's claim that rhetoric originates from the situation and Vatz's claim that the rhetoric itself creates its own situation. Rather, she proposes a deconstruction of rhetorical analysis, specifically through the lens of Jacques Derrida's thematic of différance.[8] In addition to questioning proposed views of the speaker and the situation, this lens also challenges the view of the audience as a unified, rational concept. Taken together, Biesecker suggests that the thematic of différance allows us to see the rhetorical situation as an event that does not simply convince audiences to believe or act in a certain way or represent the claims put forth by a static speaker or situation. Rather, she argues, this deconstruction reveals the ability of the rhetorical situation to actually create provisional identities and social relationships through articulation.[8]

Garret and Xiao

In their 1993 article, Mary Garrett and Xiaosui Xiao apply Bitzer's rhetorical situation model to the response of the Chinese public to the Opium Wars of the 19th century. Garrett and Xiao propose three major changes to the existing theory of the rhetorical situation:

- Elevating the audience as a defining factor of rhetorical situation, rather than the speaker, because of its role in deciding exigency, kairos ("fittingness"[9]), and constraints.

- Recognizing the power of discourse traditions within a given culture to influence the audience's perceptions, exigency, kairos, and constraints.

- Emphasizing the interactive and dialectical nature of the rhetorical situation.[9]

Rhetorical ecology

Theories leading up to rhetorical ecology

Coe

The first time the concepts of rhetoric and ecology were explored in relation to one another was in 1975 by Richard Coe.[10] In his article, "Eco-Logic for the Composition Classroom," Coe offers up eco-logic as an alternative to traditional analytical logic used in rhetoric and composition studies. The contrast between the two is that analytical logic breaks down wholes into smaller parts to examine them, while eco-logic examines the whole as itself.[10] His primary proof in favor of this type of thinking and approach to rhetoric and composition is that the meaning of the written or spoken word is relative to the context in which it is written or spoken.[10]

Cooper

A more explicit link between rhetoric and ecology was drawn in 1986 by Marilyn Cooper in her article titled "The Ecology of Writing."[11] With an acute focus on the composition classroom, Cooper critiques the notion of writing as a primarily cognitive function, positing that it ignores important social aspects of the writing process.[11] She also argues that a simply contextual perspective of writing is also insufficient; rather, an ecological view of writing extends past the immediate context of a writer and their text to examine the systems that the writer is a part of with other writers. Cooper suggests five different systems that are all intricately interwoven in the actual act of writing: ideas, purposes, interpersonal interactions, cultural norms, and textual forms.[11] Cooper illustrates this ecological model using the metaphor of a web, in that something that impacts one system will inevitably impact all the systems. Cooper also addresses the significant rhetorical concern of audience, claiming that within the ecological model, views of audience are improved as the implication is that there is really communication with a real audience happening, as opposed to an imagined audience, or generalized other.[11] For Cooper, the ecological model allows us to look at people who interact through writing and the systems making up the act of writing itself.

Edbauer's rhetorical ecology

In a 2005 article, "Unframing Models of Public Distribution: From Rhetorical Situation to Rhetorical Ecologies," Jenny Edbauer argued for an understanding of the rhetorical situation beyond the three traditional elements of audience, exigence, and constraints. Edbauer argues that the rhetorical situation lies within larger networks of meaning, or "ecologies."[1] A shift from "rhetorical situations" to "rhetorical ecologies" takes into account the complex, overlapping, and constantly shifting nature of audience, exigence, and constraints, as well as the distribution of public rhetorics. Edbauer argues that viewing rhetorical situations as ecologies shows us that "public rhetorics do not only exist in the elements of their situations, but also in the radius of their neighboring events."[1]

Challenges to rhetorical ecology

Jones

In 2021, Madison Jones published an article titled "A Counterhistory of Rhetorical Ecologies," challenging the rhetorical ecology framework.[2] In the article, he explicitly acknowledges that he is not writing off the theory as something inherently bad; rather, he is observing complications within it and offering up creative new perspectives on the topic. He begins by outlining the various environmental, colonial, and nuclear issues that arise when the metaphor of ecology is invoked.[2] Tying this back to rhetoric, he argues that spatiotemporal issues within the idea of rhetorical ecology (i.e., issues that are related to the location and timing of a rhetorical event) are directly linked back to these historical realities interwoven into the larger idea of ecology.[2] He suggests the framework of field histories as a way to acknowledge the complicated history of the field of ecology as it is used rhetorically. He particularly focuses on the need to employ place-based and community-engaged research to better understand the history of the discipline and work toward shaping a better future.[2]

Other recent theories

Gallagher

John R. Gallagher's 2015 article, "The Rhetorical Template," addresses the rhetorical situation in relation to "Web 2.0" and the templates of social networking sites, such as Facebook. Gallagher defines these Web 2.0 templates as "prefabricated designs that allow writers to create a coherent text."[12] Gallagher contends that rhetorical templates offer a new approach to making meaning within new exigency. Rhetorical templates function within constraints of the genre, but also affect the exigence and purpose by creating how the text is written and read.

Use in teaching writing

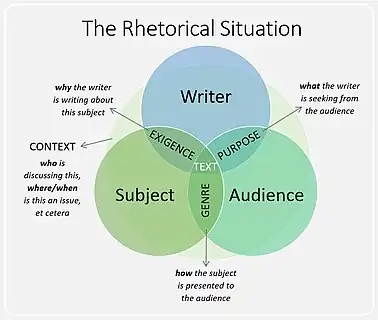

The rhetorical situation is a component of some first-year college writing courses, wherein students learn about the rhetorical situation, rhetorical analysis, and awareness of the features they must respond to from their rhetorical situation(s).[13][14][15] In this context, the rhetorical situation is taught in several parts:[16]

- Writer: the author, speaker, or other generator of the rhetoric under examination

- Exigence: the reason the author is writing about their particular subject and why they are writing about it at this moment

- Purpose: what the writer wants from the audience

- Audience: the intended (and sometimes unintended) recipients of the writer's message

- Genre: how the topic is presented by the writer to the audience

- Subject: the topic that the writer is discussing

- Context: describes the author, where and when the rhetoric is being created and/or received, etc.

- Constraints: all of the elements that can limit or alter the message's efficacy; this is sometimes grouped together with context[17]

Though some scholars, such as Douglas Downs and Elizabeth Wardle, have criticized the use of the rhetorical situation as a core component of first-year writing courses, arguing that it would be better to teach students about writing and writing studies than it would be to teach them how to write by responding to rhetorical situations.[18] In response, some others (such as Tara Boyce) have noted that both approaches appear to have their limitations, and that challenges remain regardless of approach. Boyce writes that "students, though aware of and capable of implementing [rhetorical] awareness into writing practices, most often do not. The question remains in how to adapt pedagogy to achieve this awareness and how to measure that achievement."[19]

References

- 1 2 3 Edbauer, Jenny (2005-09-01). "Unframing models of public distribution: From rhetorical situation as rhetorical ecologies". Rhetoric Society Quarterly. 35 (4): 5–24. doi:10.1080/02773940509391320. ISSN 0277-3945. S2CID 142996700.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jones, Madison (2021-08-08). "A Counterhistory of Rhetorical Ecologies". Rhetoric Society Quarterly. 51 (4): 336–352. doi:10.1080/02773945.2021.1947517. ISSN 0277-3945. S2CID 238358762.

- 1 2 Bitzer, Lloyd F. (1968). "The Rhetorical Situation". Philosophy & Rhetoric. 1 (1): 1–14. ISSN 0031-8213.

- ↑ Perelman, Chaïm (1979), "Philosophy, Rhetoric, Commonplaces", The New Rhetoric and the Humanities, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 52–61, doi:10.1007/978-94-009-9482-9_3, ISBN 978-90-277-1019-2, retrieved 2021-04-06

- ↑ Vatz, Richard E., "The Mythical Status of Situational Rhetoric: Implications for Rhetorical Critics' Relevance in the Public Arena". The Review of Communication 9 no. 1 (January 2009): 1-5.

- 1 2 Scott Consigny, "Rhetoric and Its Situations," Philosophy and Rhetoric, no. 3 (Summer 1974): 175-186

- ↑ Flower, Linda, and Hayes, John R. “The Cognition of Discovery: Defining a Rhetorical Problem.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 31, no. 1, National Council of Teachers of English, 1980, pp. 21–32.

- 1 2 3 Biesecker, Barbara A. (1989). "Rethinking the Rhetorical Situation from within the Thematic of 'Différance'". Philosophy & Rhetoric. 22 (2): 110–130. ISSN 0031-8213. JSTOR 40237580.

- 1 2 Garret, Mary, and Xiao, Xiaosui. “‘The Rhetorical Situation Revisited.’” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 23, no. 2, Informa UK Limited, Mar. 1993, pp. 30–40.

- 1 2 3 Coe, Richard M. (1975). "Eco-Logic for the Composition Classroom". College Composition and Communication. 26 (3): 232–237. doi:10.2307/356121. JSTOR 356121.

- 1 2 3 4 Cooper, Marilyn M. (1986). "The Ecology of Writing". College English. 48 (4): 364–375. doi:10.2307/377264. ISSN 0010-0994. JSTOR 377264.

- ↑ Gallagher, John R. “The Rhetorical Template.” Computers and Composition, vol. 35, Elsevier, Mar. 2015, pp. 1–11.

- ↑ Wardle, Elizabeth (2009). ""Mutt Genres" and the Goal of FYC: Can We Help Students Write the Genres of the University?". College Composition and Communication. 60 (4): 765–789. ISSN 0010-096X.

- ↑ Formo, Dawn; Neary, Kimberly Robinson (2020-05-01). "Feature: Threshold Concepts and FYC Writing Prompts: Helping Students Discover Composition's Common Knowledge with(in) Assignment Sheets". Teaching English in the Two-Year College. 47 (4): 335–364. doi:10.58680/tetyc202030647. ISSN 0098-6291.

- ↑ "First Year Program (FYC) Principles". University of North Georgia. Retrieved 2023-12-27.

- ↑ Peters, Jason; Bates, Jennifer; Martin-Elston, Erin; Johann, Sadie; Maples, Rebekah; Regan, Anne; White, Morgan. "What is the Rhetorical Situation?". WRITING ARGUMENTS IN STEM.

- ↑ Long, Liza; Minervini, Amy; Gladd, Joel (2020-08-18). "The Rhetorical Situation". WRITE WHAT MATTERS.

- ↑ Downs, Douglas; Wardle, Elizabeth (2007). "Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions: (Re)Envisionin". College Composition and Communication. 58 (4): 552–584. ISSN 0010-096X.

- ↑ "Response to Downs and Wardle and Their Critics • Locutorium". Locutorium. Retrieved 2023-12-27.