Urban resilience has conventionally been defined as the "measurable ability of any urban system, with its inhabitants, to maintain continuity through all shocks and stresses, while positively adapting and transforming towards sustainability".[1]

Therefore, a resilient city is one that assesses, plans and acts to prepare for and respond to hazards, regardless whether they are natural or human-made, sudden or slow-onset, expected or unexpected. Resilient Cities are better positioned to protect and enhance people's lives, secure development gains, and drive positive change.[1]

History

According to the urban historian Roger W. Lotchin the 2nd World War had an profound environmental impact on urban areas in the USA. By 1945 Pittsburgh and other cities along the Mississippi River experienced air pollution comparable to the Dust Bowl. The environmental impact of the 2nd World War turned urban areas around the world into shock cities.[2] Extreme cases of hard hit cities include Hiroshima, Chongqing, Stalingrad, and Dresden.[3] Environmental history first emerged as an academic research topic in the 1970s, focusing initially on rural areas.[4] Pioneers of urban environmental history include Martin Melosi, Christine Rosen, Joel A. Tarr, Peter Brimblecombe, Bill Luckin, and Christopher Hamlin.[5] Recurrent climate changes have prompted renewed interest in this academic field.[6] The concern for urban resilience in the urban planning of cities has become increasingly visible in recent years, partly because urban resilience can be used to describe the change in structure and function of urban areas. Social scientists have taken an increased interest in ecological resilience, because the links between social-ecological systems are being examined. Urban resilience is no longer the preserve of academics, urban policy documents around the globe are putting forward proposals to enhance the urban resilience of cities. The definition of urban resilience may vary, but are no longer limited to the speed at which an urban systems recover after a shock.[7]

Academic research focus

Academic discussion of urban resilience has focused primarily on three threats; climate change, natural disasters, and terrorism.[8][9]

Accordingly, resilience strategies have tended to be conceived of in terms of counter-terrorism, other disasters (earthquakes, wildfires, tsunamis, coastal flooding, solar flares, etc.), and infrastructure adoption of sustainable energy. More recently, there has been an increasing attention to the evolution of urban resilience [10] and the capability of urban systems to adapt to changing conditions. This branch of resilience theory builds on a notion of cities as highly complex adaptive systems. The implication of this insight is to move urban planning away from conventional approaches based in geometric plans to an approach informed by network science that involves less interference in the functioning of cities. Network science provides a way of linking city size to the forms of networks that are likely to enable cities to function in different ways. It can further provide insights into the potential effectiveness of various urban policies.[11] This requires a better understanding of the types of practices and tools that contribute to building urban resilience. Genealogical approaches explore the evolution of these practices over time, including the values and power relations underpinning them.

Investment decisions

Building resilience in cities relies on investment decisions that prioritize spending on activities that offer alternatives, which perform well in different scenarios. Such decisions need to take into account future risks and uncertainties. Because risk can never be fully eliminated, emergency and disaster planning is crucial.[12] Frameworks for disaster risk management, for example, offer practical opportunities for enhancing resilience.[13]

More than half of the world's human population has lived in cities since 2007, and urbanization is calculated to rise to 80% by 2050.[14] the growing urbanization over the past century has been associated with a considerable increase in urban sprawl. Resilience efforts address how individuals, communities and business not only cope on the face of multiple shocks and stresses, but also exploit opportunities for transformational development.

As one way of addressing disaster risk in urban areas, national and local governments, often supported by international funding agencies, engage in resettlement. This can be preventative, or occur after a disaster. While this reduces people's exposure to hazards, it can also lead to other problems, which can leave people more vulnerable or worse off than they were before. Resettlement needs to be understood as part of long-term sustainable development, not just as a means for disaster risk reduction.[15]

Sustainable Development Goal 11

In September 2015, world leaders adopted the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)[16] as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The goals, which build on and replace the Millennium Development Goals,[17] officially came into force on 1 January 2016 and are expected to be achieved within the next 15 years. While the SDGs are not legally binding, governments are expected to take ownership and establish national frameworks for their achievement. Countries also have the primary responsibility for follow-up and review of progress based on quality, accessible and timely data collection. National reviews will feed into regional reviews, which in turn will inform a review at the global level.

UN-Habitat's City Resilience Profiling Tool (CRPT)

As the UN Agency for Human Settlements, UN-Habitat is working to support local governments and their stakeholders build urban resilience through the City Resilience Profiling Tool (CRPT). When applied, UN-Habitat's holistic approach to increasing resiliency results in local governments that are better able to ensure the wellbeing of citizens, protect development gains and maintain functionality in the face of hazards. The tool developed by UN-Habitat to support local governments achieve resilience is the City Resilience Profiling Tool. The Tool follows various stages and UN-Habitat supports cities to maximize the impact of CRPT implementation.

Getting started Local governments and UN-Habitat connect to evaluate the needs, opportunities and context of the city and evaluate the possibility of implementing the tool in their city. WIth our local government partners, we consider the stakeholders that need to be involved in implementation, including civil society organizations, national governments, the private sectors, among others.

Engagement By signing an agreement with a UN agency, the local government is better able to work with the necessary stakeholders to plan-out risk and built-in resilience across the city.

Diagnosis The CRPT provides a framework for cities to collect the right data about the city that enables them to evaluate their resilience and identify potential vulnerability in the urban system. Diagnosis through data covers all elements of the urban system, and considers all potential hazards and stakeholders.

Resilience Actions Understanding of the entire urban system fuels effective action. The main output of the CRPT is a unique Resilience Action Plan (RAP) for each engaged city. The RAP sets out short-, medium- and long-term strategies based on the diagnosis and actions are prioritised, assigned interdepartmentally, and integrated into existing government policies and plans. The process is iterative and once resilience actions have been implemented, local governments monitor impact through the tool, which recalibrates to identify next steps.

Taking it further Resilience actions require the buy-in of all stakeholders and, in many cases, additional funding. With a detailed diagnostic, local governments can leverage the support of national governments, donors and other international organizations to work towards sustainable urban development.

To date, this approach is currently being adapted in Barcelona (Spain), Asuncion (Paraguay), Maputo (Mozambique), Port Vila (Vanuatu), Bristol (United Kingdom), Lisbon (Portugal), Yakutsk (Russia), and Dakar (Senegal). The biennial publication, Trends in Urban Resilience, also produced by UN-Habitat is tracking the most recent efforts to build urban resilience as well as the actors behind these actions and a number of case studies.[18]

Medellin Collaboration for Urban Resilience

The Medellin Collaboration for Urban Resilience (MCUR) was launched at the 7th session of the World Urban Forum in Medellín, Colombia in 2014. As a pioneering partnerships platforms, it gathers the most prominent actors committed to building resilience globally, including UNISDR, The World Bank Group, Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery, Inter-American Development Bank, Rockefeller Foundation, 100 Resilient Cities, C40, ICLEI and Cities Alliance, and it is chaired by UN-Habitat.[19]

MCUR aims to jointly collaborate on strengthening the resilience of all cities and human settlements around the world by supporting local, regional and national governments. It addresses its activity by providing knowledge and research, facilitating access to local-level finance and raising global awareness on urban resilience through policy advocacy and adaptation diplomacy efforts. Its work is devoted to achieving the main international development agendas, as it works to achieve the mandates set out in the Sustainable Development Goals, the New Urban Agenda, the Paris Agreement on Climate Change and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction.

The Medellin Collaboration conceived a platform to help local governments and other municipal professionals understand the primary utility of the vast array of tools and diagnostics designed to assess, measure, monitor and improve city-level resilience. For example, some tools are intended as rapid assessments to establish a general understanding and baseline of a city's resilience and can be self-deployed, while others are intended as a means to identify and prioritise areas for investment. The Collaboration has produced a guidebook to illustrate how cities are responding to current and future challenges by thinking strategically about design, planning, and management for building resilience. Currently, it is working in a collaborative model in six pilot cities: Accra, Bogotá, Jakarta, Maputo, Mexico City and New York City.

100 Resilient Cities and the City Resilience Index (CRI)

The Rockefeller Foundation, rates 100 cities for resilience. The Rockefeller Foundation states that: "Urban Resilience is the capacity of individuals, communities, institutions, businesses, and systems within a city to survive, adapt, and grow no matter what kinds of chronic stresses and acute shocks they experience."

A central program contributing to the achievement of SDG 11 is the Rockefeller Foundation's 100 Resilient Cities. In December 2013, The Rockefeller Foundation launched the 100 Resilient Cities initiative, which is dedicated to promoting urban resilience, defined as "the capacity of individuals, communities, institutions, businesses, and systems within a city to survive, adapt, and grow no matter what kinds of chronic stresses and acute shocks they experience".[20]

The professional services firm Arup has helped the Rockefeller Foundation develop the City Resilience Index based on extensive stakeholder consultation across a range of cities globally. The index is intended to serve as a planning and decision-making tool to help guide urban investments toward results that facilitate sustainable urban growth and the well-being of citizens. The hope is that city officials will utilize the tool to identify areas of improvement, systemic weaknesses and opportunities for mitigating risk. Its generalizable format also allows cities to learn from each other.[21]

The index is a holistic articulation of urban resilience premised on the finding that there are 12 universal factors or drivers that contribute to city resilience. What varies is their relative importance. The factors are organized into the four core dimensions of the urban resilience framework:[22]

A total of 100 cities across six continents have signed up for the Rockefeller Center's urban resilience challenge. All 100 cities have developed individual City Resilience Strategies with technical support from a Chief Resilience Officer (CRO). The CRO ideally reports directly to the city's chief executive and helps coordinate all the resilience efforts in a single city.

Medellin in Colombia qualified for the urban resilience challenge in 2013. In 2016, it won the Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize.

Urban governance

A core factor enabling progress on all other dimensions of urban resilience is urban governance. Sustainable, resilient and inclusive cities are often the outcome of good governance that encompasses effective leadership, inclusive citizen participation and efficient financing among other things. To this end, public officials increasingly have access to public data, enabling evidence-based decision making. Open data is also increasingly transforming the way local governments share information with citizens, deliver services and monitor performance. It enables simultaneously increased public access to information and more direct citizen involvement in decision-making.[23]

Digital technologies

As part of their resilience strategies, city governments are increasingly relying on digital technology as part of a city's infrastructure and service delivery systems. On the one hand, reliance on technologies and electronic service delivery has made cities more vulnerable to Phone hacking and Cyber-attacks. At the same time, information technologies have often had a positive transformative impact by supporting innovation and promoting efficiencies in urban infrastructure, thus leading to lower-cost city services. The deployment of new technologies in the initial construction of infrastructure have in some cases even allowed urban economies to leapfrog stages of development.[23] An unintended outcome of the growing digitalization of cities is the emergence of a digital divide, which can exacerbate inequality between well-connected affluent neighborhoods and business districts, on the one hand, and under-serviced and under-connected low-income neighborhoods, on the other. In response, a number of cities have introduced digital inclusion programs to ensure that all citizens have the necessary tools to thrive in an increasingly digitalized world.

Climate change

The urban impacts of climate change vary widely across geographical and developmental scales. A recent study [24] of 616 cities (home to 1.7 billion people, with a combined GDP of US$35 trillion, half of the world's total economic output), found that floods endanger more city residents than any other natural peril, followed by earthquakes and storms. Below is an attempt to define and discuss the challenges of heat waves, droughts and flooding. Resilience-boosting strategies will be introduced and outlined.

Heat waves and droughts

Heat waves are becoming increasingly prevalent as the global climate changes. The 1980 United States heat wave and drought killed 10,000 people. In 1988 a similar heat wave and drought killed 17,000 American citizens.[25] In August 2003 the UK saw record breaking summer temperatures with average temperatures persistently rising above 32 °C. Nearly 3,000 deaths were contributed to the heat wave in the UK during this period, with an increase of 42% in London alone.[26] This heat wave claimed more than 40,000 lives across Europe.[27] Research indicates that by 2040 over 50% of summers will be warmer than 2003 and by 2100 those same summer temperatures will be considered cool.[28] The 2010 northern hemisphere summer heat wave was also disastrous, with nearly 5,000 deaths occurring in Moscow.[29] In addition to deaths, these heat waves also cause other significant problems. Extended periods of heat and droughts also cause widespread crop losses, spikes in electricity demand, forest fires, air pollution and reduced biodiversity in vital land and marine ecosystems.[30] Agricultural losses from heat and drought might not occur directly within the urban area, but it certainly affects the lives of urban dwellers. Crop supply shortages can lead to spikes in food prices, food scarcity, civic unrest and even starvation in extreme cases. In terms of the direct fatalities from these heat waves and droughts, they are statistically concentrated in urban areas,[31] and this is not just in line with increased population densities, but is due to social factors and the urban heat island effect.

Urban heat islands

Urban heat island (UHI) refers to the presence of an inner-city microclimate in which temperatures are comparatively higher than in the rural surroundings. Recent studies have shown that summer daytime temperatures can reach up to 10 °C hotter in a city centre than in rural areas and between 5–6 °C warmer at night.[32] The causes of UHI are no mystery, and are mostly based on simple energy balances and geometrics. The materials commonly found in urban areas (concrete and asphalt) absorb and store heat energy much more effectively than the surrounding natural environment. The black colouring of asphalt surfaces (roads, parking lots and highways) is able to absorb significantly more electromagnetic radiation, further encouraging the rapid and effective capture and storage of heat throughout the day. Geometrics come into play as well, as tall buildings provide large surfaces that both absorb and reflect sunlight and its heat energy onto other absorbent surfaces. These tall buildings also block the wind, which limits convective cooling. The sheer size of the buildings also blocks surface heat from naturally radiating back into the cool sky at night.[33] These factors, combined with the heat generated from vehicles, air conditioners and industry ensure that cities create, absorb and hold heat very effectively.

Social factors for heat vulnerability

The physical causes of heat waves and droughts and the exacerbation of the UHI effect are only part of the equation in terms of fatalities; social factors play a role as well. Statistically, senior citizens represent the majority of heat (and cold) related deaths within urban areas[34] and this is often due to social isolation. In rural areas, seniors are more likely to live with family or in care homes, whereas in cities they are often concentrated in subsidised apartment buildings and in many cases have little to no contact with the outside world.[35] Like other urban dwellers with little or no income, most urban seniors are unlikely to own an air conditioner. This combination of factors leads to thousands of tragic deaths every season, and incidences are increasing each year.[36]

Adapting for heat and drought resilience

Greening, reflecting and whitening urban spaces

Greening urban spaces is among the most frequently mentioned strategies to address heat effects. The idea is to increase the amount of natural cover within the city. This cover can be made up of grasses, bushes, trees, vines, water, rock gardens; any natural material. Covering as much surface as possible with green space will both reduce the total quantity of thermally absorbent artificial material, but the shading effect will reduce the amount of light and heat that reaches the concrete and asphalt that cannot be replaced by greenery.[37]

Trees are among the most effective greening tool within urban environments because of their coverage/footprint ratio. Trees require a very small physical area for planting, but when mature, they provide a much larger coverage area. This both absorbs solar energy for photosynthesis (improving air quality and mitigating global warming), reducing the amount of energy being trapped and held within artificial surfaces, but also casts much-needed shade on the city and its inhabitants. Shade itself does not lower the ambient air temperature, but it greatly reduces the perceived temperature and comfort of those seeking its refuge.[38]

An increasingly popular method of preventing the so called urban heat island (UHI) is the increasing of albedo (light reflectiveness). This can be done by using reflective paints or materials where appropriate, or white and light colored paints. Glazing can also be added to windows to reduce the amount of heat that buildings or roofs generate and store.[39]

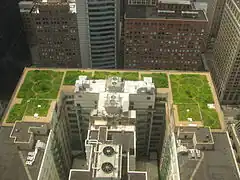

Green roofs also boost urban resilience by reducing the urban heat island effect. Additionally, green roofs improve the resilience to urban flooding. However, depaving of urban footpaths and roads has also been found to be effective in urban flood control, and may be a more cost-efficient approach.

Social strategies

There are various strategies to increase the resilience of those most vulnerable to urban heat waves. As established, these vulnerable citizens are primarily socially isolated seniors. Other vulnerable groups include young children (especially those facing abject poverty or living in informal housing), people with underlying health problems, the infirm or disabled and the homeless. Accurate and early prediction of heat waves is of fundamental importance, as it gives time for the government to issue extreme heat alerts. Urban areas must prepare and be ready to implement heat-wave emergency response initiatives. Seasonal campaigns aimed to educate the public on the risks associated with heat waves will help prepare the broad community, but in response to impending heat events more direct action is required.[40]

Local government must quickly communicate with the groups and institutions that work with heat-vulnerable populations. Cooling centres should be opened in libraries, community centres and government buildings. These centres ensure free access to air conditioning and water. In partnership with government and non-government social services, paramedics, police, firefighters, nurses and volunteers; the above-mentioned groups working with vulnerable populations should carry out regular door-to-door visits during these extreme heat scenarios. These visits should provide risk assessment, advice, bottled water (for areas without potable tap water) and the offer of free transportation to local cooling centres.[41]

Food and water supplies

Heat waves and droughts can reap massive damage on agricultural areas vital to providing food staples to urban populations. Reservoirs and aquifers quickly dry up due to increased demand on water for drinking, industrial and agricultural purposes. The result can be shortages and price spikes for food and with increasing frequency, shortages of drinking water as observed with increasing severity seasonally in China[42] and throughout most of the developing world.[43] From an agricultural standpoint, farmers can be required to plant more heat and drought-resistant crops. Agricultural practices can also be streamlined to higher levels of hydrological efficiency. Reservoirs should be expanded and new reservoirs and water towers should be constructed in areas facing critical shortages.[44] Grander schemes of damming and redirecting rivers should also be considered if possible. For saltwater coastal cities, desalination plants provide a possible solution to water shortages. Infrastructure also plays a role in resilience, as in many areas aging pipelines result in leakage and possible contamination of drinking water. In Kenya’s major cities, Nairobi and Mombasa, between 40 and 50% of drinking water is lost through leakage.[45] In these types of cases, replacements and repairs are clearly needed.

Flooding

Flooding, either from weather events, rising sea levels or infrastructure failures are a major cause of death, disease and economic losses throughout the world. Climate change and rapidly expanding urban settlements are two factors that are leading to the increasing occurrence and severity of urban flood events, especially in the developing world.[46][47][48] Storm surges can affect coastal cities and are caused by low pressure weather systems, like cyclones and hurricanes.[49] Flash floods and river floods can affect any city within a floodplain or with inadequate drainage infrastructure. These can be caused by large quantities of rain or heavy rapid snow melt. With all forms of flooding, cities are increasingly vulnerable because of the large quantity of paved and concrete surfaces. These impermeable surfaces cause massive amounts of runoff and can quickly overwhelm the limited infrastructure of storm drains, flood canals and intentional floodplains. Many cities in the developing world simply have no infrastructure to redirect floodwaters whatsoever.[50] Around the world, floods kill thousands of people every year and are responsible for billions of dollars in damages and economic losses.[51] Flooding, much like heat waves and droughts, can also wreak havoc on agricultural areas, quickly destroying large amounts of crops. In cities with poor or absent drainage infrastructure, flooding can also lead to the contamination of drinking water sources (aquifers, wells, inland waterways) with salt water, chemical pollution, and most frequently, viral and bacterial contaminants.[52]

Flood flow in urban environment

The flood flow in urbanised areas constitutes a hazard to the population and infrastructure. Some recent catastrophes included the inundations of Nîmes (France) in 1998 and Vaison-la-Romaine (France) in 1992, the flooding of New Orleans (USA) in 2005, the flooding in Rockhampton, Bundaberg, Brisbane during the 2010–2011 summer in Queensland (Australia). Flood flows in urban environments have been studied relatively recently despite many centuries of flood events.[50] Some researchers mentioned the storage effect in urban areas. Several studies looked into the flow patterns and redistribution in streets during storm events and the implication in terms of flood modelling.[53]

Some research considered the criteria for safe evacuation of individuals in flooded areas.[54] But some recent field measurements during the 2010–2011 Queensland floods showed that any criterion solely based upon the flow velocity, water depth or specific momentum cannot account for the hazards caused by the velocity and water depth fluctuations.[50] These considerations ignore further the risks associated with large debris entrained by the flow motion.[54]

Adapting for flood resilience

Urban greening

Replacing as many non-porous surfaces with green space as possible will create more areas for natural ground (and plant-based) absorption of excess water.[55] Gaining popularity are different types of green roofs. Green roofs vary in their intensity, from very thin layers of soil or rockwool supporting a variety of low or no-maintenance mosses or sedum species to large, deep, intensive roof gardens capable of supporting large plants and trees but requiring regular maintenance and more structural support.[56] The deeper the soil, the more rainwater it can absorb and therefore the more potential floodwater it can prevent from reaching the ground. One of the best strategies, if possible, is to simply create enough space for the excess water. This involves planning or expanding areas of parkland in or adjacent to the zone where flooding is most likely to occur. Excess water is diverted into these areas when necessary, as in Cardiff, around the new Millennium Stadium.[57] Floodplain clearance is another greening strategy that fundamentally removes structures and pavement built on floodplains and returns them to their natural habitat which is capable of absorbing massive quantities of water that otherwise would have flooded the built urban area.[52]

Flood-water control

Levees and other flood barriers are indispensable for cities on floodplains or along rivers and coasts. In areas with lower financial and engineering capital, there are cheaper and simpler options for flood barriers. UK engineers are currently conducting field tests of a new technology called the SELOC (Self-Erecting Low-Cost Barrier). The barrier itself lies flat on the ground, and as the water rises, the SELOC floats up, with its top edge rising with the water level. A restraint holds the barrier in the vertical position. This simple, inexpensive flood barrier has great potential for increasing urban resilience to flood events[57] and shows significant promise for developing nations with its low cost and simple, fool-proof design. The creation or expansion of flood canals and/or drainage basins can help direct excess water away from critical areas[58] and the utilisation of innovative porous paving materials on city streets and car parks allow for the absorption and filtration of excess water.[39]

During the January 2011 flood of the Brisbane River (Australia), some unique field measurements about the peak of the flood showed very substantial sediment fluxes in the Brisbane River flood plain, consistent with the murky appearance of floodwaters.[59][60] The field deployment in an inundated street of the CBD showed also some unusual features of flood flow in an urban environment linked with some local topographic effects.

Structural resilience

In most developed nations, all new developments are assessed for flood risks. The aim is to ensure flood risk is taken into account in all stages of the planning process to avoid inappropriate development in areas of high risk. When development is required in areas of high risk, structures should be built to flood-resistant standards and living or working areas should be raised well above the worst-case scenario flood levels. For existing structures in high-risk areas, funding should be allocated to i.e. raise the electrical wiring/sockets so any water that enters the home can not reach the electrics. Other solutions are to raise these structures to appropriate heights[61] or make them floating[62] or considerations should be made to relocate or rebuild structures on higher ground. A house in Mexico Beach, Florida which survived Hurricane Michael is an example of a house built to survive tidal surge.[63]

The pre-Incan Uru people of Lake Titicaca in Peru have lived on floating islands made of reeds for hundreds of years. The practice began as an innovative form of protection from competition for land by various groups, and it continues to support the Uru homeland. The manual technique is used to build homes resting on hand-made islands[64] all from simple reeds from the totora plant. Similarly, in the southern wetlands of Iraq, the Marsh Arabs (Arab al-Ahwār) have lived for centuries on floating islands and in arched buildings[65] all constructed exclusively from the local qasab reeds. Without any nails, wood, or glass, buildings are assembled by hand as quickly as within a day. Another aspect of these villages, called Al Tahla, is that the built homes can also be disassembled in a day, transported, and reassembled .

Emergency response

As with all disasters, flooding requires a specific set of disaster response plans. Various levels of contingency planning should be established, from basic medical and selective evacuation provisions involving local emergency responders right the way up to full military disaster relief plans involving air-based evacuations, search and rescue teams and relocation provisions for entire urban populations. Clear lines of responsibility and chains of command must be laid out, and tiered priority response levels should be established to address the immediate needs of the most vulnerable citizens first. For post-flooding repair and reconstruction sufficient emergency funding should be set aside proactively.[66]

US University education relating to urban resilience

The emergence of urban resilience as an educational topic in the USA has experienced an unprecedented level of growth due in large part to a series of natural disasters including the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, 2005 Hurricane Katrina, the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, and Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Two of the more well-recognized programs are Harvard Graduate School of Design's Master's program in Risk and Resilience, and Tulane University's Disaster Resilience Leadership Academy. There are also several workshops available related to the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Department of Homeland Security.

See also

- Co-benefits of climate change mitigation

- Energy security

- Human-powered transport – Transport of goods and/or people only using human muscles

- New Urbanism

- Sustainable urbanism

- Urban vitality

References

- 1 2 Mariani, Luisana. "Urban Resilience Hub". urbanresiliencehub.org. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ↑ J. R. McNeill; Richard P. Tucker; Simo Laakkonen; Timo Vuorisalo, eds. (2019). The Resilient City in World War II. Springer International Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 9783030174392.

- ↑ J. R. McNeill; Richard P. Tucker; Simo Laakkonen; Timo Vuorisalo, eds. (2019). The Resilient City in World War II. Springer International Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 9783030174392.

- ↑ J. R. McNeill; Richard P. Tucker; Simo Laakkonen; Timo Vuorisalo, eds. (2019). The Resilient City in World War II. Springer International Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 9783030174392.

- ↑ J. R. McNeill; Richard P. Tucker; Simo Laakkonen; Timo Vuorisalo, eds. (2019). The Resilient City in World War II. Springer International Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 9783030174392.

- ↑ J. R. McNeill; Richard P. Tucker; Simo Laakkonen; Timo Vuorisalo, eds. (2019). The Resilient City in World War II. Springer International Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 9783030174392.

- ↑ Ayda Eraydin; Tuna Taşan-Kok, eds. (2013). Resilience Thinking in Urban Planning. Springer Netherlands. p. 5. ISBN 9789400754768.

- ↑ Coaffee, J (2008). "Risk, resilience, and environmentally sustainable cities". Energy Policy. 36 (12): 4633–4638. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2008.09.048.

- ↑ Pickett, S. T. A.; Cadenasso, M. L.; et al. (2004). "Resilient cities: meaning, models, and metaphor for integrating the ecological, socio-economic, and planning realms". Landscape and Urban Planning. 69 (4): 373. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2003.10.035.

- ↑ Rogers, Peter (2012). Resilience and the City: change (dis)order and Disaster. London: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0754676584.

- ↑ Batty, Michael (2008). "The Size, Scale, and Shape of Cities". Science. 319 (5864): 769–771. Bibcode:2008Sci...319..769B. doi:10.1126/science.1151419. PMID 18258906. S2CID 206509775.

- ↑ The Professional Practices for Business Continuity Management, Disaster Recovery Institute International (DRI), 2017.

- ↑ Jha; et al. (2013). Building Urban Resilience: Principles, Tools, and Practice. The World Bank.

- ↑ Dowe, M. "Urbanisation and Climate Change". Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ↑ Risk-related resettlement and relocation in urban areas The Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN), accessdate 25 July 2017

- ↑ "About the Sustainable Development Goals".

- ↑ "United Nations Millennium Development Goals".

- ↑ Trends in Urban Resilience 2017

- ↑ Mariani, Luisana. "Urban Resilience Hub". urbanresiliencehub.org. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ↑ "City Resilience". www.100resilientcities.org.

- ↑ "City Resilience Index - Arup". www.arup.com.

- ↑ "City Resilience Index". 28 September 2016.

- 1 2 World Cities Report 2016: Emerging Futures. UN Habitat. 2016.

- ↑ "Mind the risk: cities under threat from natural disasters". www.swissre.com. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-06-22.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center. "Billion Dollar U.S. Weather Disasters". Archived from the original on September 15, 2001. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ↑ Office of National Statistics. "Health Statistics Quarterly" (PDF). Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ↑ Robine, Jean-Marie; et al. (2008). "Death toll exceeded 46,000 in Europe during the summer of 2003". Comptes Rendus Biologies. 331 (2): 171–8. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2007.12.001. PMID 18241810.

- ↑ CABE. "Integrate green infrastructure into urban areas". Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ↑ Sinclair, Lulu. "Death Rate Surges in Russian Heatwave". Sky News Online HD. Archived from the original on August 8, 2010. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ↑ Kane, S; Shogren, J. F. (2000). "Linking Adaptation and Mitigation in Climate Change Policy". Climatic Change. 45 (1): 83. doi:10.1023/A:1005688900676. S2CID 152456864.

- ↑ Karl, T. R.; Trenberth, K. E. (2003). "Modern Global Climate Change". Science. 302 (5651): 1719–23. Bibcode:2003Sci...302.1719K. doi:10.1126/science.1090228. PMID 14657489. S2CID 45484084.

- ↑ "London's Urban Heat Island: A Summary for Decision Makers" (PDF). Mayor of London. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 27, 2011. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ↑ Oke, T. R. (1982). "The energetic basis of the urban heat island". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 108 (455): 1–24. Bibcode:1982QJRMS.108....1O. doi:10.1002/qj.49710845502. S2CID 120122894.

- ↑ Keatinge, W. R.; Donaldson, G. C.; et al. (2000). "Heat related mortality in warm and cold regions of Europe: observational study". BMJ. 321 (7262): 670–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7262.670. PMC 27480. PMID 10987770.

- ↑ Cannuscio, C.; Block, J.; et al. (2003). "Social Capital and Successful Aging: The Role of Senior Housing". Annals of Internal Medicine. 139 (2): 395–9. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.452.3037. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-139-5_part_2-200309021-00003. PMID 12965964. S2CID 6123762.

- ↑ Bernard, S. M.; McGeehin, M. A. (2004). "Municipal Heat Wave Response Plans". Am J Public Health. 94 (9): 1520–2. doi:10.2105/AJPH.94.9.1520. PMC 1448486. PMID 15333307.

- ↑ Shashua-Bar, L.; Hoffman, M. E. (2000). "Vegetation as a climatic component in the design of an urban street: An empirical model for predicting the cooling effect of urban green areas with trees". Energy and Buildings. 31 (3): 229. doi:10.1016/s0378-7788(99)00018-3.

- ↑ Tidball, K.G; Krasnym, M.E. (2007). "From risk to resilience: What role for community greening and civic ecology in cities?" (PDF). Social Learning Towards a More Sustainable World: 152. Retrieved May 18, 2001.

- 1 2 "Urban Heat Island Mitigation". Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ↑ Weir, E. (2002). "Heat wave: first, protect the vulnerable". CMAJ. 167 (2): 169. PMC 117098. PMID 12160127. Archived from the original on July 11, 2012. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ↑ Kovats, R. S.; Kristie, L. E. (2006). "Heatwaves and public health in Europe". The European Journal of Public Health. 16 (6): 592–9. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.485.9858. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckl049. PMID 16644927. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ↑ Cheng, H.; Hu, Y.; et al. (2009). "Meeting China's Water Shortage Crisis: Current Practices and Challenges". Environmental Science & Technology. 43 (2): 240–4. Bibcode:2009EnST...43..240C. doi:10.1021/es801934a. PMID 19238946.

- ↑ Ivey, J. L.; Smithers, J.; et al. (2004). "Community Capacity for Adaptation to Climate-Induced Water Shortages: Linking Institutional Complexity and Local Actors". Environmental Management. 33 (1): 36–47. doi:10.1007/s00267-003-0014-5. PMID 14743290. S2CID 13597786.

- ↑ Pimentel, David; et al. (1997). "Water Resources: Agriculture, the Environment, and Society: an Assessment of the Status of Water Resources". BioScience. 47 (2): 97–106. doi:10.2307/1313020. JSTOR 1313020.

- ↑ Njiru, C. (2000). "Improving urban water services: private sector participation". Proceedings of the 26th WEDC Conference. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ↑ IPCC (2001). Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. p. 881.

- ↑ IPCC (2007). Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Summary for Policymakers. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Chanson, Hubert (2011). "The 2010–2011 Floods in Queensland (Australia): Observations, First Comments and Personal Experience". La Houille Blanche (1): 5–11. doi:10.1051/lhb/2011026. ISSN 0018-6368. Retrieved April 22, 2011.

- ↑ Flather, R.A.; et al. (1994). "A storm surge prediction model for the northern Bay of Bengal with application to the cyclone disaster in April 1991". Journal of Physical Oceanography. 24 (1): 172–190. Bibcode:1994JPO....24..172F. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(1994)024<0172:ASSPMF>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0485. Retrieved May 20, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Brown, Richard; Chanson, Hubert; McIntosh, Dave; Madhani, Jay (2011). Turbulent Velocity and Suspended Sediment Concentration Measurements in an Urban Environment of the Brisbane River Flood Plain at Gardens Point on 12–13 January 2011. Brisbane, Australia: The University of Queensland, School of Civil Engineering. pp. 120 pp. ISBN 978-1-74272-027-2.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ↑ Tanner, T.; Mitchell, T.; et al. (2009). "Urban Governance for Adaptation: Assessing Climate Change Resilience in Ten Asian Cities". IDS Working Papers. 2009 (315): 31. doi:10.1111/j.2040-0209.2009.00315_2.x.

- 1 2 Godschalk, D. (2003). "Urban Hazard Mitigation: Creating Resilient Cities" (PDF). Natural Hazards Review. 4 (3): 136–143. doi:10.1061/(asce)1527-6988(2003)4:3(136). Retrieved May 16, 2001.

- ↑ Werner, MGF; Hunter, NM; Bates, PD (2006). "Identifiability of Distributed Floodplain Roughness Values in Flood Extent Estimation". Journal of Hydrology. 314 (1–4): 139–157. Bibcode:2005JHyd..314..139W. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2005.03.012.

- 1 2 Chanson, H., Brown, R., McIntosh, D. (2014). "Human body stability in floodwaters: The 2011 flood in Brisbane CBD" (PDF). Hydraulic structures and society - Engineering challenges and extremes (PDF). Proceedings of the 5th IAHR International Symposium on Hydraulic Structures (ISHS2014), 25–27 June 2014, Brisbane, Australia, H. CHANSON and L. TOOMBES Editors, 9 pages. pp. 1–9. doi:10.14264/uql.2014.48. ISBN 978-1-74272-115-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Depave. From Parking Lots to Paradise | Asphalt and concrete removal from urban areas. Based in Portland, Oregon". www.depave.org. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ↑ Mentens, J.; Raes, D.; et al. (2006). "Green roofs as a tool for solving the rainwater runoff problem in the urbanized 21st century?". Landscape and Urban Planning. 77 (3): 221. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2005.02.010.

- 1 2 Nathan, S. (2009-11-18). "Urban planning engineers explore anti-flood options". Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ↑ Colten, C. E.; Kates, R. W.; Laska, S. B. Community resilience: Lessons from New Orleans and Hurricane Katrina. Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.172.1958.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Richard Brown; Hubert Chanson (2012). "Suspended sediment properties and suspended sediment flux estimates in an inundated urban environment during a major flood event". Water Resources Research. 48 (11): W11523.1–15. Bibcode:2012WRR....4811523B. doi:10.1029/2012WR012381. ISSN 0043-1397.

- ↑ Brown, Richard; Chanson, Hubert (2013). "Turbulence and Suspended Sediment Measurements in an Urban Environment during the Brisbane River Flood of January 2011". Journal of Hydraulic Engineering. 139 (2): 244–252. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)HY.1943-7900.0000666. ISSN 0733-9429. S2CID 129661565.

- ↑ Carmin, J.; Roberts, D.; Anguelovski, I. (2009). "Planning Climate Resilient Cities: Early Lessons from Early Adapters" (PDF). Paper Presented at the World Bank Urban Research Symposium on Climate Change: 29. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ↑ "WATERSTUDIO'S AMPHIBIOUS HOUSES". 4 October 2005.

- ↑ Patricia Mazzei (October 14, 2018). "Among the Ruins of Mexico Beach Stands One House, Built 'for the Big One'". The New York Times. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

The house, built of reinforced concrete, is elevated on tall pilings to allow a storm surge to pass underneath with little damage.

- ↑ "Visit These Floating Peruvian Islands Constructed From Plants".

- ↑ "7 Examples of Centuries-Old Design That Combat Climate Change". 2 March 2020.

- ↑ Coaffee, J.; D. Murakami Wood; et al. (2009). The Everyday resilience of the city: how cities respond to terrorism and disaster. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.