India is world's 4th largest consumer of electricity and world's 3rd largest renewable energy producer with 40% of energy capacity installed in the year 2022 (160 GW of 400 GW) coming from renewable sources.[1][2] Ernst & Young's (EY) 2021 Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index (RECAI) ranked India 3rd behind USA and China.[3][4] In FY2023-24, India is planning to issue 50 GW tenders for wind, solar and hybrid projects.[5] India has committed for a goal of 500 GW renewable energy capacity by 2030.[6] In line with this commitment, India's installed renewable energy capacity has been experiencing a steady upward trend. From 94.4 GW in 2021, the capacity has gone up to 119.1 GW in 2023 as of Q4.[7]

In 2016, Paris Agreement's Intended Nationally Determined Contributions targets, India made commitment of producing 50% of its total electricity from non-fossil fuel sources by 2030.[8][9] In 2018, India's Central Electricity Authority set a target of producing 50% of the total electricity from non-fossil fuels sources by 2030.[10] India has also set a target of producing 175 GW by 2022 and 500 GW by 2030 from renewable energy.[11][10][12][13]

As of September 2020, 89.22 GW solar energy is already operational, projects of 48.21 GW are at various stages of implementation and projects of 25.64 GW capacity are under various stages of bidding.[14] In 2020, 3 of the world's top 5 largest solar parks were in India including world's largest 2255 MW Bhadla Solar Park in Rajasthan and world's second-largest solar park of 2000 MW Pavgada Solar Park Tumkur in Karnataka and 1000 MW Kurnool in Andhra Pradesh.[15] Wind power in India has a strong manufacturing base with 20 manufactures of 53 different wind turbine models of international quality up to 3 MW in size with exports to Europe, United States and other countries.[14]

Solar, wind and run-of-the-river hydroelectricity are environment-friendly cheaper power sources they are used as ""must-run" sources in India to cater for the base load, and the polluting and foreign-import dependent coal-fired power is increasingly being moved from the "must-run base load" power generation to the load following power generation (mid-priced and mid-merit on-demand need-based intermittently-produced electricity) to meet the peaking demand only.[16] Some of the daily peak demand in India is already met with the renewable peaking hydro power capacity. Solar and wind power with 4-hour battery storage systems, as a source of dispatchable generation compared with new coal and new gas plants, is already cost-competitive in India without subsidy.[17]

India initiated the International Solar Alliance (ISA), an alliance of 121 countries. India was world's first country to set up a ministry of non-conventional energy resources (Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) in early 1980s) . Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI), a public sector undertaking, is responsible for the development of solar energy industry in India. Hydroelectricity is administered separately by the Ministry of Power and not included in MNRE targets.

Global comparison

Global rank

India ranks first in terms of population and accounts for 17% of the world’s population. India is globally ranked 3rd in consumption of energy. In terms of installed capacity and investment in renewable energy, the EY's Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index (RECAI) ranking in July 2021 is as follows:[3][4]

| Country | Score | RECAI Rank |

|---|---|---|

| USA | 70.7 | 1 |

| China | 68.7 | 2 |

| India | 66.2 | 3 |

Attractiveness score

The technology-specific RECAI scores (and rank) in 2021 are as follows:[3][4]

| Technology | India | USA | China |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solar PV | 62.7 (1) | 57.6 | 60.3 |

| Solar CSP power plants | 09.2 (4) | 46.2 | 54.3 |

| Hydroelectricity | 46.4 (3) | 57.6 | 60.3 |

| Biofuels | 47.4 (10) | 45.3 | 52.8 |

| Onshore wind power | 54.2 (6) | 58.1 | 55.7 |

| Offshore wind power | 28.6 (29) | 55.6 | 60.6 |

| Geothermal power | 23.2 (16) | 46.0 | 31.7 |

Future targets

The installed capacity of renewable power is 125.159 GW as of 31 March 2023.[18] The government has announced that no new coal-based capacity addition is required beyond the 50 GW under different stages of construction likely to come online between 2017 and 2022.[19]

| Target year | Renewable energy capacity target (GW) | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 2030 | 500[11] | Includes nuclear and large hydro power. Set in 2019 at United Nations Climate Change conference,[11] with 15 times solar and 2 times wind power capacity increase compared to April 2016 installed capacity. |

| 2022 | 175[20] | Excludes nuclear and large hydro power. Includes 100 GW solar, 60 GW wind, 5 small hydro, 10 GW Biomass power, and 0.168 GW Waste-to-Power.[20][12][13] |

Present installed capacity

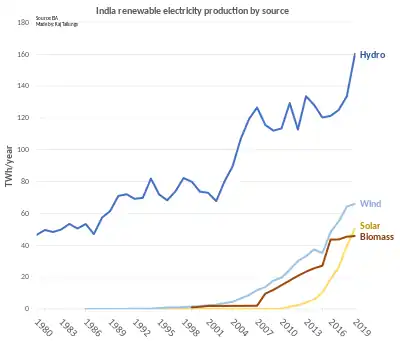

Year-wise renewable energy generation trend

Year wise renewable energy generation in TWh.[21]

| Source | 2014–15 | 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–2020 | 2020–2021 | 2021–2022 | 2022-2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Hydro | 129.2 | 121.4 | 122.3 | 126.1 | 135.0 | 156.0 | 150.3 | 151.7 | 162.06 |

| Small Hydro | 8.1 | 8.4 | 7.73 | 5.1 | 8.7 | 9.4 | 10.3 | 10.4 | 11.17 |

| Solar | 4.6 | 7.5 | 12.1 | 25.9 | 39.3 | 50.1 | 60.4 | 73.5 | 102.01 |

| Wind | 28.2 | 28.6 | 46.0 | 52.7 | 62.0 | 64.6 | 60.1 | 68.6 | 71.81 |

| Bio mass | 15.0 | 16.7 | 14.2 | 15.3 | 16.4 | 13.9 | 14.8 | 16.1 | 16.02 |

| Other | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 2.53 |

| Total | 191.0 | 187.2 | 204.1 | 228.0 | 261.8 | 294.3[22] | 297.5 | 322.6 | 365.59 |

| Total utility power | 1,105 | 1,168 | 1,236 | 1,303 | 1,372 | 1,385 | 1,373 | 1,484 | 1,617.42[23] |

| % Renewable power | 17.28% | 16.02% | 16.52% | 17.50% | 19.1% | 21.25% | 21.67% | 21.74% | 22.60% |

Grid-connected total including non-renewable and renewable

The following table shows the breakdown of existing installed capacity in March 2020 from all sources, and includes 141.6 GW from renewable sources.[24][12][13] Since 2019, the hydropower generated by the under Ministry of Power is also counted towards Ministry of New and Renewable Energy's Renewable Energy Purchase Obligation (REPO) targets, under which the DISCOMs (Distribution Companies) of various states have to source a certain percentage of their power from Renewable Energy Sources under two categories, Solar and Non-Solar.

| Type | Source | Installed Capacity (GW) | Share |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-renewable | Coal | 205.1 | 56.09% |

| Gas | 25.0 | 6.84% | |

| Diesel | 0.5 | 0.14% | |

| Nuclear | 6.7 | 0.36% | |

| Subtotal Non-renewable | 237.3 | 63% | |

| Renewable | Large hydro | 45.7 | 12.05% |

| Small hydropower | 4.7 | 1.29% | |

| Solar power | 38.8 | 10.61% | |

| Wind power | 38.7 | 10.59% | |

| Biomass power | 0.2 | 0.05% | |

| Waste-to-Power | 0.2 | 0.05% | |

| Subtotal Renewable | 135.0 | 37% | |

| Total | Both non-renewable and renewable | 365.6 | 100.00% |

Off-grid renewable energy installed capacity

Off-grid power as of 31 July 2019 (MNRE) capacity:[25]

| Source | Total Installed Capacity (GW) |

|---|---|

| SPV Systems | 0.94 |

| Biomass Gasifiers | 0.17 |

| Waste to Energy | 0.19 |

| TOTAL | 1.20 |

| Other Renewable Energy Systems | |

| Family Biogas Plants (individual units) | 50,28,000 |

| Water mills / micro hydel (Nos.) | 2,690/72 |

Renewable electricity generation

Hydroelectric power

India ranks 5th globally for installed hydroelectric power capacity.[26] As of 31 March 2020, India's installed utility-scale hydroelectric capacity was 45,699 MW, or 12.35% of its total utility power generation capacity.[24]

Additional smaller hydroelectric power units with a total capacity of 4,380 MW (1.3% of its total utility power generation capacity) have been installed.[27][24] Small hydropower, defined to be generated at facilities with nameplate capacities up to 25 MW, comes under the ambit of the Ministry of New and Renewable energy (MNRE); while large hydro, defined as above 25 MW, comes under the ambit of the Ministry of Power.[28][29]

India is endowed with vast potential of pumped hydroelectric energy storage which can be used economically for converting the non-dispatchable renewable energy like wind, solar and run of the river hydro power in to base/peak load power supply for its ultimate energy needs.[30][31]

Solar power

India is densely populated and has high solar insolation, an ideal combination for using solar power in India. Announced in November 2009, the Government of India proposed to launch its Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission under the National Action Plan on Climate Change. The program was inaugurated[33] by former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh on 11 January 2010[34] with a target of 20GW grid capacity by 2022 as well as 2GW off-grid installations, this target was later increased to 100 GW by the same date under the Narendra Modi government in the 2015 Union budget of India.[35] Achieving this National Solar Mission target would establish India in its ambition to be a global leader in solar power generation.[36] The Mission aims to achieve grid parity (electricity delivered at the same cost and quality as that delivered on the grid) by 2022.[34] The National Solar Mission is also promoted and known by its more colloquial name of "Solar India". The earlier objectives of the mission were to install 1,000 MW of power by 2013 and cover 20×106 m2 (220×106 sq ft) with collectors by the end of the final phase of the mission in 2022.[37]

On 30 November 2015, the Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi and the President of France Francois Hollande launched the International Solar Alliance. The ISA is an alliance of 121 solar rich countries lying partially or fully between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn, several countries outside of this area are also involved with the organization. The ISA aims to promote and develop solar power amongst its members and has the objective of mobilising $1 trillion of investment by 2030.[38] As of August, 2019, the Indian Oil Corporation stated that it wants to invest ₹25,000 crore in renewable energy projects.[39]

Much of the country does not have an electrical grid, so one of the first applications of solar power was for water pumping, to begin replacing India's forty to fifty lakh diesel powered water pumps, each consuming about 3.5 kilowatts, and off-grid lighting. Some large projects have been proposed, and a 35,000 km2 (14,000 sq mi) area of the Thar Desert has been set aside for solar power projects, sufficient to generate 700 to 2,100 gigawatts. Solar power in India has been growing at a rate of 113% yoy[40] and now dropped to around ₹4.34 (5.4¢ US) per kWh, which is around 18% lower than the average price for electricity generated by coal-fired plants.[41][42]

As part of India's ambitious solar programme the central government has set up a US$350 million fund and the Yes Bank will loan US$5 billion to finance solar projects (c. January 2018). The bidding process for the addition of 115 GW to January 2018 renewable energy levels was completed by the end of 2019–2020.[43]

India is also the home to the world's first and only 100% solar-powered airport, located at Cochin, Kerala.[44] India also has a wholly 100% solar-powered railway station in Guwhati, Assam. India's first and the largest floating solar power plant was constructed at Banasura Sagar reservoir in Wayanad, Kerala.[45]

The Indian Solar Loan Programme, supported by the United Nations Environment Programme has won the prestigious Energy Globe World award for Sustainability for helping to establish a consumer financing program for solar home power systems. Over three years more than 16,000 solar home systems have been financed through 2,000 bank branches, particularly in rural areas of South India where the electricity grid does not yet extend.[46][47]

Launched in 2003, the Indian Solar Loan Programme was a four-year partnership between UNEP, the UNEP Risoe Centre, and two of India's largest banks, the Canara Bank and Syndicate Bank.[47]

Nuclear power

As of November 2020, India had 10 nuclear reactors under-construction with a combined capacity of 8 GW and 23 existing nuclear reactors in operation in 7 nuclear power plants with a total installed capacity of 7.4 GW (3.11% of total power generation in India).[48][49][50] Nuclear power is the fifth-largest source of electricity in India after coal, hydroelectricity, solar, wind and gas power.

Bioenergy

Biomass

India is an ideal environment for biomass production given its tropical location, sunshine and rains. The country's vast agricultural potential provides agro-residues which can be used to meet energy needs, both in heat and power applications.[51] According to IREDA "Biomass is capable of supplementing the coal to the tune of about 26 crore (260 million) tonnes", "saving of about ₹25,0000 crore, every year."[52] It is estimated that the potential for biomass energy in India includes 16,000 MW from biomass energy and a further 3,500 MW from bagasse cogeneration.[52] Biomass materials that can be used for power generation include bagasse, rice husk, straw, cotton stalk, coconut shells, soya husk, de-oiled cakes, coffee waste, jute wastes, groundnut shells and sawdust.

| Number | Type of Agro residues | Quantity(Million Tonnes / annum) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Straws of various pulses & cereals | 225.50 |

| 2 | Bagasse | 31.00 |

| 3 | Rice Husk | 10.00 |

| 4 | Groundnut shell | 11.10 |

| 5 | Stalks | 2.00 |

| 6 | Various Oil Stalks | 4.50 |

| 7 | Others | 65.90 |

| Total | 350.00 |

Biogas

In 2018, India has set target to produce 1.5 crore (15 million) tons (62 mmcmd) of biogas/bio-CNG by installing 5,000 large scale commercial type biogas plants which can produce daily 12.5 tons of bio-CNG by each plant.[53][54] The rejected organic solids from biogas plants can be used after Torrefaction in the existing coal fired plants to reduce coal consumption.

The number of small family type biogas plants reached 3.98 million.[14]

Bio protein

Synthetic methane (SNG) generated using electricity from carbon neutral renewable power or Bio CNG can be used to produce protein rich feed for cattle, poultry and fish economically by cultivating Methylococcus capsulatus bacteria culture with tiny land and water foot print.[55][56][57] The carbon dioxide gas produced as by product from these bio protein plants can be recycled in the generation of SNG. Similarly, oxygen gas produced as by product from the electrolysis of water and the methanation process can be consumed in the cultivation of bacteria culture. With these integrated plants, the abundant renewable power potential in India can be converted in to high value food products without any water pollution or green house gas (GHG) emissions for achieving food security at a faster pace with lesser people deployment in agriculture / animal husbandry sector.[58]

Waste to energy

Every year, about 5.5 crore (55 million) tonnes of municipal solid waste (MSW) and 3,800 crore (38 billion) litres of sewage are generated in the urban areas of India. In addition, large quantities of solid and liquid wastes are generated by industries. Waste generation in India is expected to increase rapidly in the future. As more people migrate to urban areas and as incomes increase, consumption levels are likely to rise, as are rates of waste generation. It is estimated that the amount of waste generated in India will increase at a per capita rate of approximately 1–1.33% annually. This has significant impacts on the amount of land that is and will be needed for disposal, economic costs of collecting and transporting waste, and the environmental consequences of increased MSW generation levels.[59]

India has had a long involvement with anaerobic digestion and biogas technologies. Waste water treatment plants in the country have been established which produce renewable energy from sewage gas. However, there is still significant untapped potential.[60] Also wastes from the distillery sector are on some sites converted into biogas to run in a gas engine to generate onsite power. Prominent companies in the waste to energy sector include:[61]

- A2Z Group of companies

- Hanjer Biotech Energies

- Ramky Enviro Engineers Ltd

- Arka BRENStech Pvt Ltd

- Hitachi Zosen India Pvt Limited

- Clarke Energy

- ORS Group

- Punjab Renewable Energy Systems Pvt. Ltd.

Biofuels and organic chemicals

Biomass is going to play a crucial role in making India self-sufficient in the energy sector and carbon neutral.[62]

Ethanol

India imports 85% of petrol products with import cost of $55 billion in 2020–21, India has set a target of blending 20% ethanol in petrol by 2025 resulting in import substitution saving of US$4 billion or ₹30,000 crore, and India provides financial assistance for manufacturing ethanol from rice, wheat, barley, corn, sorghum, sugarcane, sugar beet, etc.[63] Ethanol market penetration reached its highest figure of a 10% blend rate in India in 2022 and is currently on track to achieve 20% ethanol blending by 2025 as envisioned in National Policy on Biofuels.[64]

Ethanol is produced from sugarcane molasses and partly from grains and can be blended with gasoline. Sugarcane or sugarcane juice may not be used for the production of ethanol in India. Government is also encouraging 2G ethanol commercial production using biomass as feed stock.[65]

Biodiesel

The market for biodiesel remains at an early stage in India with the country achieving a minimal blend rate with diesel of 0.001% in 2016.[64] Initially development was focussed on the jatropha (jatropha curcas) plant as the most suitable inedible oilseed for biodiesel production. Some Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) studies have shown India's potential for production of low carbon Jatropha and Algae based biodiesel.[66] Development of biodiesel from jatropha has met a number of agronomic and economic restraints and attention is now moving towards other feedstock technologies which utilize used cooking oils, other unusable oil fractions, animal fat and inedible oils.[64] Biodiesel and also Biopropane are produced from non-edible vegetable oils, used cooking oil, waste animal fats, etc.[67][68]

Wind power

The development of wind power in India began in the 1990s, and has significantly increased in the last few years. Although a relative newcomer to the wind industry compared with Denmark or US, domestic policy support for wind power has led India to become the country with the fourth largest installed wind power capacity in the world.[69]

As of 30 June 2018 the installed capacity of wind power in India was 34,293 MW,[12] mainly spread across Tamil Nadu (7,269.50 MW), Maharashtra (4,100.40 MW), Gujarat (3,454.30 MW), Rajasthan (2,784.90 MW), Karnataka (2,318.20 MW), Andhra Pradesh (746.20 MW) and Madhya Pradesh (423.40 MW)[70] Wind power accounts for 10% of India's total installed power capacity.[71] India has set an ambitious target to generate 60,000 MW of electricity from wind power by 2022.[72]

Wind power installations occupy only 2% of the wind farm area facilitating the rest of the area for agriculture, plantations, etc.[73] The Indian Government's Ministry of New and Renewable Energy announced a new wind-solar hybrid policy in May 2018.[74] This means that the same piece of land will be used to house both wind farms and solar panels.

Largest wind farms in India[75]

| Power plant | Location | State | MWe | Producer | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kutch Wind Farm (Gujarat Hybrid Renewable Energy Park) | Kutch | Gujarat | 11,500 (wind)

+ 11,500 (solar + wind) |

Adani Group[76] Suzlon[77] | [78][79] |

| Muppandal Wind Farm | Muppandal Wind | Tamil Nadu | 1500 | [80] | |

| Jaisalmer Wind Park | Suzlon Energy | Rajasthan | 1300 | [81] | |

| Brahmanvel windfarm | Parakh Agro Industries | Maharashtra | 528 | [82] | |

| Dhalgaon windfarm | Gadre Marine Exports | Maharashtra | 300 | [83] | |

| Chakala windfarm | Suzlon Energy | Maharashtra | 200 | [84] | |

| Vankusawade Wind Park | Suzlon Energy | Maharashtra | 200 | [85] | |

| Vaspet Windfarm | ReNew Power | Maharashtra | 140 | [86] | |

| Sadla Wind Farm | SJVN | Gujarat | 50 | [7][87] |

See also

- List of power stations in India

- Electricity sector in India

- Hydroelectric power in India

- International Renewable Energy Agency

- Renewable energy by country

- Bureau of Energy Efficiency

- Renewable energy in Asia

- Renewable energy commercialization

- Renewable energy debate

- Fossil fuel phase-out

- World energy resources and consumption

- Ministry of New and Renewable Energy

- Ocean thermal energy conversion

- List of countries by electricity production from renewable sources

References

- ↑ "2021 Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index (RECAI)". www.ey.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ↑ Koundal, Aarushi (26 November 2020). "India's renewable power capacity is the fourth largest in the world, says PM Modi". ETEnergyworld. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 2019 Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index (RECAI) Archived 20 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Ernst & Young, 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ↑ "Government to Bid Out 50 GW of Solar, Wind, and RTC Projects in FY24". Mercom India. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ↑ "India's 450 GW renewable energy goal by 2030 doable, says John Kerry". The Hindu. PTI. 20 October 2021. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - 1 2 admin (1 July 2023). "List of Green Energy Stocks That Can Make Your Portfolio Future Proof". Dayco India. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ↑ "Here are India's INDC objectives and how much it will cost". The Indian Express. 2 October 2015. Archived from the original on 16 November 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ↑ "INDC submission" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- 1 2 Safi, Michael (22 December 2016). "India plans nearly 60% of electricity capacity from non-fossil fuels by 2027". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 "PM Modi vows to more than double India's non-fossil fuel target to 450GW". The Times of India. 23 September 2019. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 "Physical Progress (Achievements)". Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, Govt. of India. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, Physical Progress (Achievements)". Archived from the original on 3 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Press Information Bureau". pib.nic.in. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ↑ "With 2245 MW of Commissioned Solar Projects, World's Largest Solar Park is Now at Bhadl". 19 March 2020. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ↑ "Infographic: Illustrative curve for change in PLF of coal plants". Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ↑ "Solar and wind now the cheapest power source says Bloomberg NEF". Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ↑ "State-wise installed capacity of Renewable Power as of 31.03.2023" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ↑ "Report on Payment dues of RE Generators up to 31.07.2019" (PDF). Central Electricity Authority, Ministry of Power, Govt. of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- 1 2 Saluja, Nishtha; Singh, Sarita (5 June 2018). "Renewable energy target now 227 GW, will need $50 billion more in investments, MNRE". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 13 September 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ↑ "Summary of All India Provisional Renewable Energy Generation" (PDF). CEA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ↑ "Renewable energy generation data, March 2020" (PDF). CEA. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ↑ "Monthly power generation data, March 2023" (PDF). CEA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- 1 2 3 "All India Installed Capacity of Utility Power Stations". Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ↑ "Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, Physical Progress (Achievements)". Archived from the original on 3 May 2018.

- ↑ "India overtakes Japan with fifth-largest hydropower capacity in the world". Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ "Renewable Energy Physical Progress as on 31-03-2016". Ministry of New & Renewable Energy, GoI. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ↑ "Executive Summary Power Sector February 2017" (PDF). report. Central Electricity Authority, Ministry of Power, Govt. of India. 28 February 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ↑ "Small Hydro". Government of India Ministry of New and Renewable Energy. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ↑ "Interactive map showing the feasible locations of PSS projects in India". Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- ↑ "Getting to 100% renewables requires cheap energy storage. But how cheap?". 9 August 2019. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ↑ "Global Solar Atlas". Archived from the original on 27 September 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ↑ JNNSM Inauguration

- 1 2 "Scheme – Documents". www.mnre.gov.in. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ↑ "Revision of cumulative targets under National Solar Mission from 20,000 MW by 2021–22 to 1,00,000 MW". pib.nic.in. Archived from the original on 30 October 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ↑ Saito, Yolanda (8 December 2011). "INSIDE STORY: Transforming India into a solar power". Climate and Development Knowledge Network. Centre for International Sustainable Development Law: International Development Law Organisation. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ Sethi, Nitin (18 November 2009). "India targets 1,000mw solar power in 2013". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012.

- ↑ "International Solar Alliance, ISA's Journey so far" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ↑ Ranganath, Ramya (22 August 2019). "Indian Oil Corporation Plans to Invest ₹250 Billion in Renewable Energy Projects". Mercom India. Archived from the original on 22 August 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ↑ Kenning, Tom (19 October 2016). "India surpasses 1GW rooftop solar with grid parity for most C&I consumers". report. PVTECH. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ↑ Dockrill, Peter (20 April 2017). "India surpasses 1GW rooftop solar with grid parity for most C&I consumers". report. scienceAlert. Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ↑ McGrath, Matt (1 June 2017). "Five effects of a US pull-out from Paris climate deal". BBC. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ↑ Govt to set up $350 million fund to finance solar projects Archived 18 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Hindustan Times, 18 Jan 2018.

- ↑ Crew, Bec (20 August 2015). "India Establishes World's First 100 Percent Solar-Powered Airport". report. scienceAlert. Archived from the original on 30 April 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ↑ "India's largest floating solar power plant opens in Kerala – Watt a sight!". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ↑ "Consumer financing program for solar home systems in southern India". Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- 1 2 UNEP wins Energy Globe award Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Kudankulam nuclear plant begins power generation". Mumbai Mirror. 22 October 2013. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ↑ "India Installed Capacity" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 May 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ↑ "Plants under operation". npcil.nic.in. (A Government of India Enterprise), Department of Atomic Energy. Archived from the original on 4 August 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ↑ "The potential for advanced biofuels in India: Assessing the availability of feedstocks and deployable technologies" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency Ltd. | Bio Energy". www.ireda.gov.in. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ↑ "Compressed biogas to beat petrol and diesel with 30% higher mileage". Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ↑ "Rs 20,000 crore to be invested in Odisha in bio gas sector". Archived from the original on 17 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ↑ "BioProtein Production" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ↑ "Food made from natural gas will soon feed farm animals – and us". Archived from the original on 12 October 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ↑ "New venture selects Cargill's Tennessee site to produce Calysta FeedKind® Protein". Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ↑ "Assessment of environmental impact of FeedKind protein" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ↑ Emmanual, William. "Energy Alternatives India". EAI. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ↑ Electricity from sewage in India Archived 19 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine, www.clarke-energy.com, retrieved 15 August 2014

- ↑ Emmanual, William. "Energy ALternatives India". Energy ALternatives India. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ↑ "Carbon Neutral Fuels and Chemicals from Standalone Biomass Refineries" (PDF). Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ↑ Hussain, Siraj (1 July 2021). "India wants to use food grain stock for ethanol. That's a problem in a hungry country". ThePrint. Archived from the original on 2 July 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 "PM Modi rolls out 20% ethanol-blended petrol in 11 States/UTs". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ↑ "Cabinet okays ethanol projects' funding". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ↑ Ajayebi, Atta; Gnansounou, Edgard; Kenthorai Raman, Jegannathan (1 December 2013). "Comparative life cycle assessment of biodiesel from algae and jatropha: A case study of India". Bioresource Technology. 150: 429–437. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2013.09.118. ISSN 0960-8524.

- ↑ "47 lakh kg used cooking oil collected since Aug; 70% converted into bio-diesel". Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ↑ "Neste delivers first batch of 100% renewable propane to European market". 19 March 2018. Archived from the original on 22 July 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ↑ "Global statistics". Global Wind Energy Council. Archived from the original on 3 October 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "Energy Statistics 2015" (PDF). Central Statistics Office, Govt. of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "Executive summary of Power Sector as on 31-03-2016" (PDF). Central Electricity authority, GoI. July 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "Physical Progress (Achievements)" (PDF). Ministry of New and Renewable Energy. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "How Much Land Would It Require To Get Most Of Our Electricity From Wind & Solar?". NREL. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ↑ "Does hybrid energy policy make sense for India? Find out". Moneycontrol News. 22 May 2018. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ "Wind farm list". Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ↑ www.ETEnergyworld.com. "Adani New Industries installs India's largest wind turbine, taller than Statue of Unity - ET EnergyWorld". ETEnergyworld.com. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ↑ "Suzlon surpasses 1100 MW milestone at Asia's largest wind farm in Kutch, Gujarat". Suzlon.

- ↑ "Kutch (India) - Wind farms - Online access - The Wind Power". www.thewindpower.net. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ↑ "Explained: A look at India's sprawling renewable energy park, coming up on its border with Pakistan". The Indian Express. 5 December 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ↑ "Muppandal windfarm". Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ↑ "Jaisalmer windfarm". Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ↑ "Brahmanvel windfarm (India)". Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ↑ "Dhalgaon windfarm". Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ↑ "Chakala windfarm". Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ↑ "Vankusawade Wind Park windfarm". Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ↑ "Vaspet windfarm". Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ↑ Carmen (18 January 2022). "Power plant profile: Sadla Wind Farm-SJVN, India". Power Technology. Archived from the original on 8 July 2023. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

External links

- India's National Power Portal and Dashboard

- India's Central Electricity Authority

- Renewable energy world magazine

![]() Media related to Renewable energy in India at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Renewable energy in India at Wikimedia Commons