| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Lead tetroxide [1] | |

| Other names

Minium, red lead, triplumbic tetroxide | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.851 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 1479 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| Pb3O4 | |

| Molar mass | 685.6 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Vivid orange crystals |

| Density | 8.3 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 500 °C (decomposition) |

| Vapor pressure | 1.3 kPa (at 0 °C) |

| Structure | |

| Tetragonal, tP28 | |

| P42/mbc, No. 135 | |

| Hazards | |

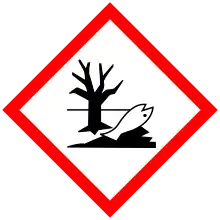

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H272, H302, H332, H360, H373, H410 | |

| P201, P220, P273, P308+P313, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Related compounds | |

| Lead(II) oxide Lead(IV) oxide | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Lead(II,IV) oxide, also called red lead or minium, is the inorganic compound with the formula Pb3O4. A bright red or orange solid, it is used as pigment, in the manufacture of batteries, and rustproof primer paints. It is an example of a mixed valence compound, being composed of both Pb(II) and Pb(IV) in the ratio of two to one.[2]

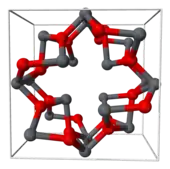

Structure

Lead(II,IV) oxide may be thought of as lead(II) orthoplumbate(IV) [Pb2+]2[PbO4−4].[3] It has a tetragonal crystal structure at room temperature, which then transforms to an orthorhombic (Pearson symbol oP28, Space group Pbam, No. 55) form at temperature 170 K (−103 °C). This phase transition only changes the symmetry of the crystal and slightly modifies the interatomic distances and angles.[4]

Part of tetragonal red lead's crystal structure

Part of tetragonal red lead's crystal structure

Preparation

Lead(II,IV) oxide is prepared by calcination of lead(II) oxide (PbO; also called litharge) in air at about 450–480 °C:[5]

- 6 PbO + O2 → 2 Pb3O4

The resulting material is contaminated with PbO. If a pure compound is desired, PbO can be removed by a potassium hydroxide solution:

- PbO + KOH + H2O → K[Pb(OH)3]

Another method of preparation relies on annealing of lead(II) carbonate (cerussite) in air:

- 6 PbCO3 + O2 → 2 Pb3O4 + 6 CO2

Yet another method is oxidative annealing of white lead:

- 3 Pb2CO3(OH)2 + O2 → 2 Pb3O4 + 3 CO2 + 3 H2O

In solution, lead(II,IV) oxide can be prepared by reaction of potassium plumbate with lead(II) acetate, yielding yellow insoluble lead(II,IV) oxide monohydrate Pb3O4·H2O, which can be turned into the anhydrous form by gentle heating:

- K2PbO3 + 2 Pb(OCOCH3)2 + H2O → Pb3O4 + 2 KOCOCH3 + 2 CH3COOH

Natural minium is uncommon, forming only in extreme oxidizing conditions of lead ore bodies. The best known natural specimens come from Broken Hill, New South Wales, Australia, where they formed as the result of a mine fire.[6]

Reactions

Red lead is virtually insoluble in water and in ethanol. However, it is soluble in hydrochloric acid present in the stomach, and is therefore toxic when ingested. It also dissolves in glacial acetic acid and a diluted mixture of nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide.

When heated to 500 °C, it decomposes to lead(II) oxide and oxygen. At 580 °C, the reaction is complete.

- 2 Pb3O4 → 6 PbO + O2

Nitric acid dissolves the lead(II) oxide component, leaving behind the insoluble lead(IV) oxide:

- Pb3O4 + 4 HNO3 → PbO2 + 2 Pb(NO3)2 + 2 H2O

With iron oxides and with elemental iron, lead(II,IV) oxide forms insoluble iron(II) and iron(III) plumbates, which is the basis of the anticorrosive properties of lead-based paints applied to iron objects.

Use

Red lead has been used as a pigment for primer paints for iron objects. Due to its toxicity, its use is being limited. It finds limited use in some amateur pyrotechnics as a delay charge and was used in the past in the manufacture of dragon's egg pyrotechnic stars.

Red lead is used as a curing agent in some polychloroprene rubber compounds. It is used in place of magnesium oxide to provide better water resistance properties.

Red lead was used for engineer's scraping, before being supplanted by engineer's blue.

It is also used as an adulterating agent in turmeric powder.

Physiological effects

When inhaled, lead(II,IV) oxide irritates the lungs. In case of high dose, the victim experiences a metallic taste, chest pain, and abdominal pain. When ingested, it is dissolved in the gastric acid and absorbed, leading to lead poisoning. High concentrations can be absorbed through skin as well, and it is important to follow safety precautions when working with lead-based paint.

Long-term contact with lead(II,IV) oxide may lead to accumulation of lead compounds in organisms, with development of symptoms of acute lead poisoning. Chronic poisoning displays as agitation, irritability, vision disorders, hypertension, and a grayish facial hue.

Lead(II,IV) oxide was shown to be carcinogenic for laboratory animals. Its carcinogenicity for humans was not proven.

History

This compound's Latin name minium originates from the Minius, a river in northwest Iberia where it was first mined.

Lead(II,IV) oxide was used as a red pigment in ancient Rome, where it was prepared by calcination of white lead. In the ancient and medieval periods it was used as a pigment in the production of illuminated manuscripts, and gave its name to the minium or miniature, a style of picture painted with the colour.

Made into a paint with linseed oil, red lead was used as a durable paint to protect exterior ironwork. In 1504 the portcullis at Stirling Castle in Scotland was painted with red lead, as were cannons including Mons Meg.[7]

As a finely divided powder, it was also sprinkled on dielectric surfaces to study Lichtenberg figures.

In traditional Chinese medicine, red lead is used to treat ringworms and ulcerations, though the practice is limited due to its toxicity. Also, azarcón, a Mexican folk remedy for gastrointestinal disorders, contains up to 95% lead(II,IV) oxide.[8]

It was also used before the 18th century as medicine.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ "VOLUNTARY RISK ASSESSMENT REPORT ON LEAD AND SOME INORGANIC LEAD COMPOUNDS". Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ↑ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ↑ Egon Wiberg; Nils Wiberg; Arnold Frederick Holleman (2001). Inorganic chemistry. Academic Press. p. 920. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- ↑ Gavarri, J; Weigel, Dominique; Hewat, A. W. (1978). "Oxydes de plomb. IV. Évolution structurale de l'oxyde Pb3O4 entre 240 et 5 K et mécanisme de la transition" [Lead oxides. IV. Structural evolution of the oxide Pb3O4 between 240 and 5 K and mechanism of transition]. Journal of Solid State Chemistry. 23 (3–4): 327. Bibcode:1978JSSCh..23..327G. doi:10.1016/0022-4596(78)90081-6.

- ↑ Carr, Dodd S. "Lead Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a15_249. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ↑ Minium

- ↑ James Balfour Paul, Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1900), p. 277.

- ↑ Bose, A.; Vashistha, K; O'Loughlin, B. J. (1983). "Azarcón por empacho – another cause of lead toxicity". Pediatrics. 72: 108–118. doi:10.1542/peds.72.1.106. S2CID 37730169.

- ↑ "The London Lancet: A Journal of British and Foreign Medicine, Physiology, Surgery, Chemistry, Criticism, Literature and News". 1853.