| Polymer science |

|---|

|

In polymer chemistry, free-radical polymerization (FRP) is a method of polymerization by which a polymer forms by the successive addition of free-radical building blocks (repeat units). Free radicals can be formed by a number of different mechanisms, usually involving separate initiator molecules. Following its generation, the initiating free radical adds (nonradical) monomer units, thereby growing the polymer chain.

Free-radical polymerization is a key synthesis route for obtaining a wide variety of different polymers and materials composites. The relatively non-specific nature of free-radical chemical interactions makes this one of the most versatile forms of polymerization available and allows facile reactions of polymeric free-radical chain ends and other chemicals or substrates. In 2001, 40 billion of the 110 billion pounds of polymers produced in the United States were produced by free-radical polymerization.[1]

Free-radical polymerization is a type of chain-growth polymerization, along with anionic, cationic and coordination polymerization.

Initiation

Initiation is the first step of the polymerization process. During initiation, an active center is created from which a polymer chain is generated. Not all monomers are susceptible to all types of initiators. Radical initiation works best on the carbon–carbon double bond of vinyl monomers and the carbon–oxygen double bond in aldehydes and ketones.[1] Initiation has two steps. In the first step, one or two radicals are created from the initiating molecules. In the second step, radicals are transferred from the initiator molecules to the monomer units present. Several choices are available for these initiators.

Types of initiation and the initiators

- Thermal decomposition

- The initiator is heated until a bond is homolytically cleaved, producing two radicals (Figure 1). This method is used most often with organic peroxides or azo compounds.[3]

Figure 1: Thermal decomposition of dicumyl peroxide

Figure 1: Thermal decomposition of dicumyl peroxide - Photolysis

- Radiation cleaves a bond homolytically, producing two radicals (Figure 2). This method is used most often with metal iodides, metal alkyls, and azo compounds.[3]

Figure 2: Photolysis of azoisobutylnitrile (AIBN)

Figure 2: Photolysis of azoisobutylnitrile (AIBN) - High absorptivity in the 300–400 nm range.

- Efficient generation of radicals capable of attacking the alkene double bond of vinyl monomers.

- Adequate solubility in the binder system (prepolymer + monomer).

- Should not impart yellowing or unpleasant odors to the cured material.

- The photoinitiator and any byproducts resulting from its use should be non-toxic.

- Redox reactions

- Reduction of hydrogen peroxide or an alkyl hydrogen peroxide by iron (Figure 3).[3] Other reductants such as Cr2+, V2+, Ti3+, Co2+, and Cu+ can be employed in place of ferrous ion in many instances.[1]

Figure 3: Redox reaction of hydrogen peroxide and iron. |

- Persulfates

- The dissociation of a persulfate in the aqueous phase (Figure 4). This method is useful in emulsion polymerizations, in which the radical diffuses into a hydrophobic monomer-containing droplet.[3]

Figure 4: Thermal degradation of a persulfate

Figure 4: Thermal degradation of a persulfate - Ionizing radiation

- α-, β-, γ-, or x-rays cause ejection of an electron from the initiating species, followed by dissociation and electron capture to produce a radical (Figure 5).[3]

Figure 5: The three steps involved in ionizing radiation: ejection, dissociation, and electron-capture

Figure 5: The three steps involved in ionizing radiation: ejection, dissociation, and electron-capture - Electrochemical

- Electrolysis of a solution containing both monomer and electrolyte. A monomer molecule will receive an electron at the cathode to become a radical anion, and a monomer molecule will give up an electron at the anode to form a radical cation (Figure 6). The radical ions then initiate free radical (and/or ionic) polymerization. This type of initiation is especially useful for coating metal surfaces with polymer films.[5]

Figure 6: (Top) Formation of radical anion at the cathode; (bottom) formation of radical cation at the anode

Figure 6: (Top) Formation of radical anion at the cathode; (bottom) formation of radical cation at the anode - Plasma

- A gaseous monomer is placed in an electric discharge at low pressures under conditions where a plasma (ionized gaseous molecules) is created. In some cases, the system is heated and/or placed in a radiofrequency field to assist in creating the plasma.[1]

- Sonication

- High-intensity ultrasound at frequencies beyond the range of human hearing (16 kHz) can be applied to a monomer. Initiation results from the effects of cavitation (the formation and collapse of cavities in the liquid). The collapse of the cavities generates very high local temperatures and pressures. This results in the formation of excited electronic states, which in turn lead to bond breakage and radical formation.[1]

- Ternary initiators

- A ternary initiator is the combination of several types of initiators into one initiating system. The types of initiators are chosen based on the properties they are known to induce in the polymers they produce. For example, poly(methyl methacrylate) has been synthesized by the ternary system benzoyl peroxide and 3,6-bis(o-carboxybenzoyl)-N-isopropylcarbazole and di-η5-indenylzirconium dichloride (Figure 7).[6][7]

-N-isopropylcarbazole_%252B_di-%CE%B75-indenylzicronium_dichloride.svg.png.webp) Figure 7: benzoyl peroxide + 3,6-bis(o-carboxybenzoyl)-N-isopropylcarbazole + di-η5-indenylzicronium dichloride

Figure 7: benzoyl peroxide + 3,6-bis(o-carboxybenzoyl)-N-isopropylcarbazole + di-η5-indenylzicronium dichloride

Initiator efficiency

Due to side reactions, not all radicals formed by the dissociation of initiator molecules actually add monomers to form polymer chains. The efficiency factor f is defined as the fraction of the original initiator which contributes to the polymerization reaction. The maximal value of f is 1, but typical values range from 0.3 to 0.8.[8]

The following types of reactions can decrease the efficiency of the initiator.

- Primary recombination

- Two radicals recombine before initiating a chain (Figure 8). This occurs within the solvent cage, meaning that no solvent has yet come between the new radicals.[3]

- Other recombination pathways

- Two radical initiators recombine before initiating a chain, but not in the solvent cage (Figure 9).[3]

- Side reactions

- One radical is produced instead of the three radicals that could be produced (Figure 10).[3]

Figure 10: Reaction of polymer chain R with other species in reaction |

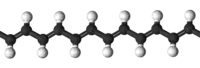

Propagation

During polymerization, a polymer spends most of its time in increasing its chain length, or propagating. After the radical initiator is formed, it attacks a monomer (Figure 11).[9] In an ethene monomer, one electron pair is held securely between the two carbons in a sigma bond. The other is more loosely held in a pi bond. The free radical uses one electron from the pi bond to form a more stable bond with the carbon atom. The other electron returns to the second carbon atom, turning the whole molecule into another radical. This begins the polymer chain. Figure 12 shows how the orbitals of an ethylene monomer interact with a radical initiator.[10]

Once a chain has been initiated, the chain propagates (Figure 13) until there are no more monomers (living polymerization) or until termination occurs. There may be anywhere from a few to thousands of propagation steps depending on several factors such as radical and chain reactivity, the solvent, and temperature.[11][12] The mechanism of chain propagation is as follows:

Termination

Chain termination is inevitable in radical polymerization due to the high reactivity of radicals. Termination can occur by several different mechanisms. If longer chains are desired, the initiator concentration should be kept low; otherwise, many shorter chains will result.[3]

- Combination of two active chain ends: one or both of the following processes may occur.

- Combination: two chain ends simply couple together to form one long chain (Figure 14). One can determine if this mode of termination is occurring by monitoring the molecular weight of the propagating species: combination will result in doubling of molecular weight. Also, combination will result in a polymer that is C2 symmetric about the point of the combination.[10]

Figure 14: Termination by the combination of two poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) polymers.

Figure 14: Termination by the combination of two poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) polymers. - Radical disproportionation: a hydrogen atom from one chain end is abstracted to another, producing a polymer with a terminal unsaturated group and a polymer with a terminal saturated group (Figure 15).[5]

Figure 15: Termination by disproportionation of poly(methyl methacrylate).

Figure 15: Termination by disproportionation of poly(methyl methacrylate).

- Combination: two chain ends simply couple together to form one long chain (Figure 14). One can determine if this mode of termination is occurring by monitoring the molecular weight of the propagating species: combination will result in doubling of molecular weight. Also, combination will result in a polymer that is C2 symmetric about the point of the combination.[10]

- Combination of an active chain end with an initiator radical (Figure 16).[3]

Figure 16: Termination of PVC by reaction with radical initiator.

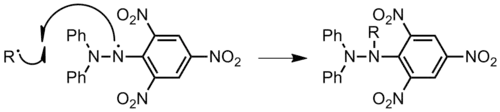

Figure 16: Termination of PVC by reaction with radical initiator. - Interaction with impurities or inhibitors. Oxygen is the common inhibitor. The growing chain will react with molecular oxygen, producing an oxygen radical, which is much less reactive (Figure 17). This significantly slows down the rate of propagation.

Figure 17: Inhibition of polystyrene propagation due to reaction of polymer with molecular oxygen.

Figure 17: Inhibition of polystyrene propagation due to reaction of polymer with molecular oxygen. Figure 18: Inhibition of polymer chain, R, by DPPH.

Figure 18: Inhibition of polymer chain, R, by DPPH.

Chain transfer

Contrary to the other modes of termination, chain transfer results in the destruction of only one radical, but also the creation of another radical. Often, however, this newly created radical is not capable of further propagation. Similar to disproportionation, all chain-transfer mechanisms also involve the abstraction of a hydrogen or other atom. There are several types of chain-transfer mechanisms.[3]

- To solvent: a hydrogen atom is abstracted from a solvent molecule, resulting in the formation of radical on the solvent molecules, which will not propagate further (Figure 19).

Figure 19: Chain transfer from polystyrene to solvent.

Figure 19: Chain transfer from polystyrene to solvent. - To monomer: a hydrogen atom is abstracted from a monomer. While this does create a radical on the affected monomer, resonance stabilization of this radical discourages further propagation (Figure 20).[3]

Figure 20: Chain transfer from polypropylene to monomer.

Figure 20: Chain transfer from polypropylene to monomer. - To initiator: a polymer chain reacts with an initiator, which terminates that polymer chain, but creates a new radical initiator (Figure 21). This initiator can then begin new polymer chains. Therefore, contrary to the other forms of chain transfer, chain transfer to the initiator does allow for further propagation. Peroxide initiators are especially sensitive to chain transfer.[3]

Figure 21: Chain transfer from polypropylene to di-t-butyl peroxide initiator.

Figure 21: Chain transfer from polypropylene to di-t-butyl peroxide initiator. - To polymer: the radical of a polymer chain abstracts a hydrogen atom from somewhere on another polymer chain (Figure 22). This terminates the growth of one polymer chain, but allows the other to branch and resume growing. This reaction step changes neither the number of polymer chains nor the number of monomers which have been polymerized, so that the number-average degree of polymerization is unaffected.[13]

Figure 22: Chain transfer from polypropylene to backbone of another polypropylene.

Figure 22: Chain transfer from polypropylene to backbone of another polypropylene.

Effects of chain transfer: The most obvious effect of chain transfer is a decrease in the polymer chain length. If the rate of transfer is much larger than the rate of propagation, then very small polymers are formed with chain lengths of 2-5 repeating units (telomerization).[14] The Mayo equation estimates the influence of chain transfer on chain length (xn): . Where ktr is the rate constant for chain transfer and kp is the rate constant for propagation. The Mayo equation assumes that transfer to solvent is the major termination pathway.[3][15]

Methods

There are four industrial methods of radical polymerization:[3]

- Bulk polymerization: reaction mixture contains only initiator and monomer, no solvent.

- Solution polymerization: reaction mixture contains solvent, initiator, and monomer.

- Suspension polymerization: reaction mixture contains an aqueous phase, water-insoluble monomer, and initiator soluble in the monomer droplets (both the monomer and the initiator are hydrophobic).

- Emulsion polymerization: similar to suspension polymerization except that the initiator is soluble in the aqueous phase rather than in the monomer droplets (the monomer is hydrophobic, and the initiator is hydrophilic). An emulsifying agent is also needed.

Other methods of radical polymerization include the following:

- Template polymerization: In this process, polymer chains are allowed to grow along template macromolecules for the greater part of their lifetime. A well-chosen template can affect the rate of polymerization as well as the molar mass and microstructure of the daughter polymer. The molar mass of a daughter polymer can be up to 70 times greater than those of polymers produced in the absence of the template and can be higher in molar mass than the templates themselves. This is because of retardation of the termination for template-associated radicals and by hopping of a radical to the neighboring template after reaching the end of a template polymer.[16]

- Plasma polymerization: The polymerization is initiated with plasma. A variety of organic molecules including alkenes, alkynes, and alkanes undergo polymerization to high molecular weight products under these conditions. The propagation mechanisms appear to involve both ionic and radical species. Plasma polymerization offers a potentially unique method of forming thin polymer films for uses such as thin-film capacitors, antireflection coatings, and various types of thin membranes.[1]

- Sonication: The polymerization is initiated by high-intensity ultrasound. Polymerization to high molecular weight polymer is observed but the conversions are low (<15%). The polymerization is self-limiting because of the high viscosity produced even at low conversion. High viscosity hinders cavitation and radical production.[1]

Reversible deactivation radical polymerization

Also known as living radical polymerization, controlled radical polymerization, reversible deactivation radical polymerization (RDRP) relies on completely pure reactions, preventing termination caused by impurities. Because these polymerizations stop only when there is no more monomer, polymerization can continue upon the addition of more monomer. Block copolymers can be made this way. RDRP allows for control of molecular weight and dispersity. However, this is very difficult to achieve and instead a pseudo-living polymerization occurs with only partial control of molecular weight and dispersity.[16] ATRP and RAFT are the main types of complete radical polymerization.

- Atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP): based on the formation of a carbon-carbon bond by atom transfer radical addition. This method, independently discovered in 1995 by Mitsuo Sawamoto[17] and by Jin-Shan Wang and Krzysztof Matyjaszewski,[18][19] requires reversible activation of a dormant species (such as an alkyl halide) and a transition metal halide catalyst (to activate dormant species).[3]

- Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain-Transfer Polymerization (RAFT): requires a compound that can act as a reversible chain-transfer agent, such as dithio compound.[3]

- Stable Free Radical Polymerization (SFRP): used to synthesize linear or branched polymers with narrow molecular weight distributions and reactive end groups on each polymer chain. The process has also been used to create block co-polymers with unique properties. Conversion rates are about 100% using this process but require temperatures of about 135 °C. This process is most commonly used with acrylates, styrenes, and dienes. The reaction scheme in Figure 23 illustrates the SFRP process.[20]

Figure 23: Reaction scheme for SFRP.

Figure 23: Reaction scheme for SFRP. Figure 24: TEMPO molecule used to functionalize the chain ends.

Figure 24: TEMPO molecule used to functionalize the chain ends.

Kinetics

In typical chain growth polymerizations, the reaction rates for initiation, propagation and termination can be described as follows:

where f is the efficiency of the initiator and kd, kp, and kt are the constants for initiator dissociation, chain propagation and termination, respectively. [I] [M] and [M•] are the concentrations of the initiator, monomer and the active growing chain.

Under the steady-state approximation, the concentration of the active growing chains remains constant, i.e. the rates of initiation and of termination are equal. The concentration of active chain can be derived and expressed in terms of the other known species in the system.

In this case, the rate of chain propagation can be further described using a function of the initiator and monomer concentrations[21][22]

The kinetic chain length v is a measure of the average number of monomer units reacting with an active center during its lifetime and is related to the molecular weight through the mechanism of the termination. Without chain transfer, the kinetic chain length is only a function of propagation rate and initiation rate.[23]

Assuming no chain-transfer effect occurs in the reaction, the number average degree of polymerization Pn can be correlated with the kinetic chain length. In the case of termination by disproportionation, one polymer molecule is produced per every kinetic chain:

Termination by combination leads to one polymer molecule per two kinetic chains:[21]

Any mixture of both these mechanisms can be described by using the value δ, the contribution of disproportionation to the overall termination process:

If chain transfer is considered, the kinetic chain length is not affected by the transfer process because the growing free-radical center generated by the initiation step stays alive after any chain-transfer event, although multiple polymer chains are produced. However, the number average degree of polymerization decreases as the chain transfers, since the growing chains are terminated by the chain-transfer events. Taking into account the chain-transfer reaction towards solvent S, initiator I, polymer P, and added chain-transfer agent T. The equation of Pn will be modified as follows:[24]

It is usual to define chain-transfer constants C for the different molecules

- , , , ,

Thermodynamics

In chain growth polymerization, the position of the equilibrium between polymer and monomers can be determined by the thermodynamics of the polymerization. The Gibbs free energy (ΔGp) of the polymerization is commonly used to quantify the tendency of a polymeric reaction. The polymerization will be favored if ΔGp < 0; if ΔGp > 0, the polymer will undergo depolymerization. According to the thermodynamic equation ΔG = ΔH – TΔS, a negative enthalpy and an increasing entropy will shift the equilibrium towards polymerization.

In general, the polymerization is an exothermic process, i.e. negative enthalpy change, since addition of a monomer to the growing polymer chain involves the conversion of π bonds into σ bonds, or a ring–opening reaction that releases the ring tension in a cyclic monomer. Meanwhile, during polymerization, a large amount of small molecules are associated, losing rotation and translational degrees of freedom. As a result, the entropy decreases in the system, ΔSp < 0 for nearly all polymerization processes. Since depolymerization is almost always entropically favored, the ΔHp must then be sufficiently negative to compensate for the unfavorable entropic term. Only then will polymerization be thermodynamically favored by the resulting negative ΔGp.

In practice, polymerization is favored at low temperatures: TΔSp is small. Depolymerization is favored at high temperatures: TΔSp is large. As the temperature increases, ΔGp become less negative. At a certain temperature, the polymerization reaches equilibrium (rate of polymerization = rate of depolymerization). This temperature is called the ceiling temperature (Tc). ΔGp = 0.[25]

Stereochemistry

The stereochemistry of polymerization is concerned with the difference in atom connectivity and spatial orientation in polymers that has the same chemical composition.

Hermann Staudinger studied the stereoisomerism in chain polymerization of vinyl monomers in the late 1920s, and it took another two decades for people to fully appreciate the idea that each of the propagation steps in the polymer growth could give rise to stereoisomerism. The major milestone in the stereochemistry was established by Ziegler and Natta and their coworkers in 1950s, as they developed metal based catalyst to synthesize stereoregular polymers. The reason why the stereochemistry of the polymer is of particular interest is because the physical behavior of a polymer depends not only on the general chemical composition but also on the more subtle differences in microstructure.[26] Atactic polymers consist of a random arrangement of stereochemistry and are amorphous (noncrystalline), soft materials with lower physical strength. The corresponding isotactic (like substituents all on the same side) and syndiotactic (like substituents of alternate repeating units on the same side) polymers are usually obtained as highly crystalline materials. It is easier for the stereoregular polymers to pack into a crystal lattice since they are more ordered and the resulting crystallinity leads to higher physical strength and increased solvent and chemical resistance as well as differences in other properties that depend on crystallinity. The prime example of the industrial utility of stereoregular polymers is polypropene. Isotactic polypropene is a high-melting (165 °C), strong, crystalline polymer, which is used as both a plastic and fiber. Atactic polypropene is an amorphous material with an oily to waxy soft appearance that finds use in asphalt blends and formulations for lubricants, sealants, and adhesives, but the volumes are minuscule compared to that of isotactic polypropene.

When a monomer adds to a radical chain end, there are two factors to consider regarding its stereochemistry: 1) the interaction between the terminal chain carbon and the approaching monomer molecule and 2) the configuration of the penultimate repeating unit in the polymer chain.[5] The terminal carbon atom has sp2 hybridization and is planar. Consider the polymerization of the monomer CH2=CXY. There are two ways that a monomer molecule can approach the terminal carbon: the mirror approach (with like substituents on the same side) or the non-mirror approach (like substituents on opposite sides). If free rotation does not occur before the next monomer adds, the mirror approach will always lead to an isotactic polymer and the non-mirror approach will always lead to a syndiotactic polymer (Figure 25).[5]

However, if interactions between the substituents of the penultimate repeating unit and the terminal carbon atom are significant, then conformational factors could cause the monomer to add to the polymer in a way that minimizes steric or electrostatic interaction (Figure 26).[5]

Reactivity

Traditionally, the reactivity of monomers and radicals are assessed by the means of copolymerization data. The Q–e scheme, the most widely used tool for the semi-quantitative prediction of monomer reactivity ratios, was first proposed by Alfrey and Price in 1947.[27] The scheme takes into account the intrinsic thermodynamic stability and polar effects in the transition state. A given radical and a monomer are considered to have intrinsic reactivities Pi and Qj, respectively.[28] The polar effects in the transition state, the supposed permanent electric charge carried by that entity (radical or molecule), is quantified by the factor e, which is a constant for a given monomer, and has the same value for the radical derived from that specific monomer. For addition of monomer 2 to a growing polymer chain whose active end is the radical of monomer 1, the rate constant, k12, is postulated to be related to the four relevant reactivity parameters by

The monomer reactivity ratio for the addition of monomers 1 and 2 to this chain is given by[28][29]

For the copolymerization of a given pair of monomers, the two experimental reactivity ratios r1 and r2 permit the evaluation of (Q1/Q2) and (e1 – e2). Values for each monomer can then be assigned relative to a reference monomer, usually chosen as styrene with the arbitrary values Q = 1.0 and e = –0.8.[29]

Applications

Free radical polymerization has found applications including the manufacture of polystyrene, thermoplastic block copolymer elastomers,[30] cardiovascular stents,[31] chemical surfactants[32] and lubricants. Block copolymers are used for a wide variety of applications including adhesives, footwear and toys.

Academic research

Free radical polymerization allows the functionalization of carbon nanotubes.[33] CNTs intrinsic electronic properties lead them to form large aggregates in solution, precluding useful applications. Adding small chemical groups to the walls of CNT can eliminate this propensity and tune the response to the surrounding environment. The use of polymers instead of smaller molecules can modify CNT properties (and conversely, nanotubes can modify polymer mechanical and electronic properties).[30] For example, researchers coated carbon nanotubes with polystyrene by first polymerizing polystyrene via chain radical polymerization and subsequently mixing it at 130 °C with carbon nanotubes to generate radicals and graft them onto the walls of carbon nanotubes (Figure 27).[34] Chain growth polymerization ("grafting to") synthesizes a polymer with predetermined properties. Purification of the polymer can be used to obtain a more uniform length distribution before grafting. Conversely, “grafting from”, with radical polymerization techniques such as atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) or nitroxide-mediated polymerization (NMP), allows rapid growth of high molecular weight polymers.

Radical polymerization also aids synthesis of nanocomposite hydrogels.[35] These gels are made of water-swellable nano-scale clay (especially those classed as smectites) enveloped by a network polymer. Aqueous dispersions of clay are treated with an initiator and a catalyst and the organic monomer, generally an acrylamide. Polymers grow off the initiators that are in turn bound to the clay. Due to recombination and disproportionation reactions, growing polymer chains bind to one another, forming a strong, cross-linked network polymer, with clay particles acting as branching points for multiple polymer chain segments.[36] Free radical polymerization used in this context allows the synthesis of polymers from a wide variety of substrates (the chemistries of suitable clays vary). Termination reactions unique to chain growth polymerization produce a material with flexibility, mechanical strength and biocompatibility.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Odian, George (2004). Principles of Polymerization (4th ed.). New York: Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0-471-27400-1.

- ↑ Jenkins, A. D.; Kratochvíl, P.; Stepto, R. F. T.; Suter, U. W. (1996). "Glossary of basic terms in polymer science (IUPAC Recommendations 1996)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 68 (12): 2287–2311. doi:10.1351/pac199668122287. S2CID 98774337.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Cowie, J. M. G.; Arrighi, Valeria (2008). Polymers: Chemistry and Physics of Modern Materials (3rd ed.). Scotland: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-9813-1.

- 1 2 Hageman, H. J. (1985). "Photoinitiators for Free Radical Polymerization". Progress in Organic Coatings. 13 (2): 123–150. doi:10.1016/0033-0655(85)80021-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stevens, Malcolm P. (1999). Polymer Chemistry: An Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512444-6.

- 1 2 Islamova, R. M.; Puzin, Y. I.; Kraikin, V. A.; Fatykhov, A. A.; Dzhemilev, U. M. (2006). "Controlling the Polymerization of Methyl Methacrylate with Ternary Initiating Systems". Russian Journal of Applied Chemistry. 79 (9): 1509–1513. doi:10.1134/S1070427206090229. S2CID 94433190.

- 1 2 Islamova, R. M.; Puzin, Y. I.; Fatykhov, A. A.; Monakov, Y. B. (2006). "A Ternary Initiating System for Free Radical Polymerization of Methyl Methacrylate". Polymer Science, Series B. 48 (3): 130–133. doi:10.1134/S156009040605006X.

- ↑ Fried, Joel R. Polymer Science & Technology (2nd ed., Prentice-Hall 2003) p.36 ISBN 0-13-018168-4

- ↑ "Addition Polymerization". Materials World Modules. June 2009. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- 1 2 "Polymer Synthesis". Case Western Reserve University. 2009. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ↑ Leach, Mark R. "Radical Chemistry". Chemogenesis. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ Pojman, John A.; Jason Willis; Dionne Fortenberry; Victor Ilyashenko; Akhtar M. Khan (1995). "Factors affecting propagating fronts of addition polymerization: Velocity, front curvature, temperature profile, conversion, and molecular weight distribution". Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 33 (4): 643–652. Bibcode:1995JPoSA..33..643P. doi:10.1002/pola.1995.080330406.

- ↑ Rudin, Alfred The Elements of Polymer Science and Engineering (Academic Press 1982) p.220 ISBN 0-12-601680-1

- ↑ Rudin, Alfred The Elements of Polymer Science and Engineering (Academic Press 1982) p.212 ISBN 0-12-601680-1

- ↑ The Mayo equation for chain transfer should not be confused with the Mayo–Lewis equation for copolymers.

- 1 2 Colombani, Daniel (1997). "Chain-Growth Control in Free Radical Polymerization". Progress in Polymer Science. 22 (8): 1649–1720. doi:10.1016/S0079-6700(97)00022-1.

- ↑ Kato, M; Kamigaito, M; Sawamoto, M; Higashimura, T (1995). "Polymerization of Methyl Methacrylate with the Carbon Tetrachloride / Dichlorotris-(triphenylphosphine)ruthenium(II) / Methylaluminum Bis(2,6-di-tert-butylphenoxide) Initiating System: Possibility of Living Radical Polymerization". Macromolecules. 28 (5): 1721–1723. Bibcode:1995MaMol..28.1721K. doi:10.1021/ma00109a056.

- ↑ Wang, J-S; Matyjaszewski, K (1995). "Controlled/"living" radical polymerization. Atom transfer radical polymerization in the presence of transition-metal complexes". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117 (20): 5614–5615. doi:10.1021/ja00125a035.

- ↑ "The 2011 Wolf Prize in Chemistry". Wolf Fund. Archived from the original on 17 May 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- 1 2 "Stable Free Radical Polymerization". Xerox Corp. 2010. Archived from the original on 28 November 2003. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- 1 2 Cowie, J. M. G. (1991). Polymers: Chemistry and Physics of Modern Materials (2nd ed.). Blackie (USA: Chapman & Hall). pp. 58–60. ISBN 978-0-216-92980-7.

- ↑ Rudin, Alfred The Elements of Polymer Science and Engineering (Academic Press 1982) pp.195-9 ISBN 0-12-601680-1

- ↑ Rudin, Alfred The Elements of Polymer Science and Engineering (Academic Press 1982) p.209 ISBN 0-12-601680-1

- ↑ Rudin, Alfred The Elements of Polymer Science and Engineering (Academic Press 1982) p.214 ISBN 0-12-601680-1

- ↑ Fried, Joel R. Polymer Science & Technology (2nd ed., Prentice-Hall 2003) p.39 ISBN 0-13-018168-4

- ↑ Clark, Jim (2003). "The Polymerization of Alkenes". ChemGuide. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ↑ Alfrey, Turner; Price, Charles C. (1947). "Relative reactivities in vinyl copolymerization". Journal of Polymer Science. 2 (1): 101–106. Bibcode:1947JPoSc...2..101A. doi:10.1002/pol.1947.120020112.

- 1 2 Allcock H.R., Lampe F.W. and Mark J.E. Contemporary Polymer Chemistry (3rd ed., Pearson Prentice-Hall 2003) p.364 ISBN 0-13-065056-0

- 1 2 Rudin, Alfred The Elements of Polymer Science and Engineering (Academic Press 1982) p.289 ISBN 0-12-601680-1

- 1 2 Braunecker, W. A.; K. Matyjaszewski (2007). "Controlled/living radical polymerization: Features, developments, and perspectives". Progress in Polymer Science. 32 (1): 93–146. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2006.11.002.

- ↑ Richard, R. E.; M. Schwarz; S. Ranade; A. K. Chan; K. Matyjaszewski; B. Sumerlin (2005). "Evaluation of acrylate-based block copolymers prepared by atom transfer radical polymerization as matrices for paclitaxel delivery from coronary stents". Biomacromolecules. 6 (6): 3410–3418. doi:10.1021/bm050464v. PMID 16283773.

- ↑ Burguiere, C.; S. Pascual; B. Coutin; A. Polton; M. Tardi; B. Charleux; K. Matyjaszewski; J. P. Vairon (2000). "Amphiphilic block copolymers prepared via controlled radical polymerization as surfactants for emulsion polymerization". Macromolecular Symposia. 150: 39–44. doi:10.1002/1521-3900(200002)150:1<39::AID-MASY39>3.0.CO;2-D.

- ↑ Homenick, C. M.; G. Lawson; A. Adronov (2007). "Polymer grafting of carbon nanotubes using living free-radical polymerization". Polymer Reviews. 47 (2): 265–270. doi:10.1080/15583720701271237. S2CID 96213227.

- ↑ Lou, X. D.; C. Detrembleur; V. Sciannamea; C. Pagnoulle; R. Jerome (2004). "Grafting of alkoxyamine end-capped (co)polymers onto multi-walled carbon nanotubes". Polymer. 45 (18): 6097–6102. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2004.06.050. hdl:2268/8255.

- ↑ Haraguchi, K. (2008). "Nanocomposite hydrogels". Current Opinion in Solid State and Materials Science. 11 (3–4): 47–54. Bibcode:2007COSSM..11...47H. doi:10.1016/j.cossms.2008.05.001.

- ↑ Haraguchi, K.; Takehisa T. (2002). "Nanocomposite hydrogels: a unique organic-inorganic network structure with extraordinary mechanical, optical, and swelling/de-swelling properties". Advanced Materials. 14 (16): 1120–1123. doi:10.1002/1521-4095(20020816)14:16<1120::AID-ADMA1120>3.0.CO;2-9.