| Queen Victoria Building | |

|---|---|

%252C_Queen_Victoria_Building_--_2019_--_3580.jpg.webp) The Queen Victoria Building, as viewed from George Street | |

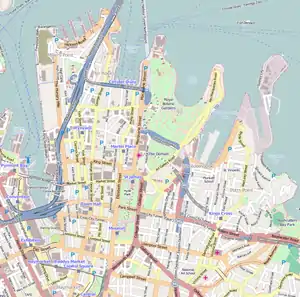

Queen Victoria Building Location in the Sydney central business district | |

| Alternative names | QVB |

| Etymology | Queen Victoria |

| General information | |

| Type |

|

| Architectural style | Romanesque revival |

| Location | 429–481 George Street, Sydney, New South Wales |

| Country | Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°52′18″S 151°12′24″E / 33.871758°S 151.206666°E |

| Current tenants | Various |

| Groundbreaking | December 1893 (Foundation stone) |

| Construction started | 1893 |

| Completed | 1898 |

| Opened |

|

| Renovated |

|

| Renovation cost | A$48 million (2006) |

| Client | Council of the City of Sydney |

| Owner | Vicinity Centres |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Sydney sandstone clad walls, brick and concrete, steel roof structure with concrete and fibreglass domes painted to look like concrete |

| Floor count | Four, including basement |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | George McRae |

| Structural engineer | George Massey |

| Other designers | William Priestly MacIntosh |

| Main contractor | Edwin & Henry Phippard |

| Known for | Royal Clock |

| Renovating team | |

| Architect(s) |

|

| Other designers | Freeman Rembel (2006) |

| Website | |

| www | |

| Official name | Queen Victoria Building; QVB |

| Type | State heritage (built) |

| Criteria | a., b., c., d., e., f., g. |

| Designated | 5 March 2010 |

| Reference no. | 1814 |

| Type | Market building |

| Category | Commercial |

The Queen Victoria Building (abbreviated as the QVB) is a heritage-listed late-nineteenth-century building located at 429–481 George Street in the Sydney central business district, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Designed by the architect George McRae, the Romanesque Revival building was constructed between 1893 and 1898 and is 30 metres (98 ft) wide by 190 metres (620 ft) long. The domes were built by Ritchie Brothers, a steel and metal company that also built trains, trams and farm equipment. The building fills a city block bounded by George, Market, York, and Druitt Streets. Designed as a marketplace, it was used for a variety of other purposes, underwent remodelling, and suffered decay until its restoration and return to its original use in the late twentieth century. The property is owned by the City of Sydney and was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 5 March 2010.[1]

History

Site and precursors

The site has been under the control of the council of the City of Sydney since 1842, when Sydney Town was incorporated.[2]: page:40 It was previously the location for municipal markets, the first of which, a "simple storehouse", was put up by Gregory Blaxland.[2]: page:40 Under Governor Macquarie's leadership, it was subsequently envisaged as a "grand civic square" by architect Francis Greenway. In the 1830s, "four substantial stone halls" were built to the design of Ambrose Hallen[2]: page:40 and later the site was selected for the construction of "a marvellous centre of trade".[3][4][2]: pages:40, 54

Design

_Queen_Victoria_Building_2.JPG.webp)

The building, on the "scale of a cathedral"[5] was designed by George McRae, a Scottish architect who had emigrated to Sydney in 1884.[6] At the time, Sydney was undergoing a building boom and since in architecture "no one school or style predominated", McRae produced four designs for the building in different styles (Gothic, Renaissance, Queen Anne and Romanesque) from which the council could choose.[2]: page:50 The council's choice of Victorian Romanesque style conveys the influences of American architect Henry Hobson Richardson. The use of columns, arches, and a prodigal amount of detail such as was used by McRae in the chosen design are typical of Richardsonian Romanesque, an eclectic style identifiably established between 1877 and 1886.[7] The dominant feature of the building is the central dome which consists of an interior glass dome and a copper-sheathed exterior, topped by a domed cupola. Smaller domes of various sizes are on the rooftop, including ones on each upper corner of the rectangular building. Stained-glass windows, including a cartwheel window depicting the arms of the City of Sydney, allow light into the central area, and the roof itself incorporates arched skylights running lengthways north and south from the central dome. The colonnades, arches, balustrades and cupolas are of typically intricate Victorian style.

.jpg.webp)

The site, an entire city block, had previously been occupied by a produce market and the Central Police Court. These uses ceased in 1891 and the land was purchased by Sydney City Council. The Australasian Builder and Contractors' News described the four designs in July 1893 as "scholarly Renaissance", "picturesque Queen Anne", "classic Gothic" and "American Romanesque". The style chosen was the last and the foundation stone was laid in December 1893 by the Mayor, Sir William Manning. This foundation stone was a five-tonne block of granite, levered and lowered into position at the corner of George and Druitt Streets. The ceremony was the first of a series in which successive mayors laid stones and plaques to mark the progress of construction. The building was notable for its employment in the expansive barrel-form roof of engineering systems which were very advanced at the time of construction. McRae is considered by architectural historians to have been one of the leading protagonists of the new construction methods and materials which were then beginning to break down the conservatism of building techniques. In achieving the strength and space of the building McRae used steel, iron, concrete, reinforcing, machine-made bricks, glass, imported tiles, fire-proofing, riveting and hydraulics on an unprecedented scale. The huge building was finally completed and opened with great ceremony by Mayor Matthew Harris on 21 July 1898. Harris said that the building was intended to be more than a municipal market. "With judicious management", he said, "a marvellous centre of trade will be established here."[1]

Naming

In 1897, the council resolved to "dedicate the new market buildings", then still under construction, to Queen Victoria and to name them The Queen Victoria Market Buildings in commemoration of her Diamond Jubilee:

"...in order to mark in a fitting manner the unprecedented and glorious reign of her Majesty the Queen, so fruitful in blessings to the British people in every land ... ".

The councillors decided not to ask for the Queen's assent, in part because it would have made it "necessary to have the Royal Coat of Arms on the building".[8] After the markets originally held in the building were relocated in 1910, the name was amended in 1918 to "Queen Victoria Buildings". Finally, in 1987, the council rescinded the 1918 resolution and named it the "Queen Victoria Building".

Construction

The building was constructed between 1893 and 1898 by the Phippard Brothers (Henry, born 1854 and Edwin, born 1864), "the leading building contractors of Sydney", whose quarries at Bowral and Waverley supplied the trachyte and sandstone respectively.[9][10]

Opening

.jpg.webp)

The building was officially opened on Thursday 21 July 1898.[2]: page:54 and provided a business environment for tailors, mercers, hairdressers, florists and coffee shops as well as showrooms and a concert hall.[11] In the evening there was a grand ball for more than a thousand guests held in the adjacent Town Hall.[12] at which the then Lord Mayor of Sydney, Matthew Harris,[13] made a speech that reflected "faith in the future, the great theme of the Victorian age of optimism", by saying:[2]: page:54

A less costly building would have provided ample market accommodation. But it would have been short-sighted to have only studied the present to the exclusion of that great future which far-seeing men will agree will be almost infinite in possibilities.

The Druitt Street entrance was opened by the Lady Mayoress using a commemorative solid gold key on which was a model of the main dome and the smaller cupolas, "worth a good deal more than £50", made by Fairfax and Roberts and presented by the Phippard Brothers.[14] The building was illuminated by about 1,000 Welsbach incandescent burners, equal in lighting power to about 70,000 candles, producing "floods of light" that even in the basement was judged to be "perfect".[14]

Early uses

A public lending library was planned as early as 1899[15] and both the City of Sydney Library and the Electricity Department were long-time occupants.[2]: page:76

Mei Quong Tart's tearoom, Elite Hall, was formally opened by the Mayor of Sydney, Matthew Harris, in 1898. The tea rooms were on the ground floor near the centre of the markets, fronting George Street. A plush-carpeted staircase led to the function hall on the first floor. The Elite Hall had capacity for nearly 500 people and included a stage with an elaborately carved proscenium. At the other end was the Elite Dining Saloon, described as having 'elegant appointments'.

Subsequent uses

%252C_George_Street_Sydney%252C_1917_A-00041531.tif.jpg.webp)

The original concept was for an internal shopping street 186-metre (611 ft)-long with two levels of shops on either side. In 1917 and 1935 alterations converted the interior to office space with shops to the external street frontages.[1][16]

In the first few decades the QVB had the atmosphere of an oriental bazaar, and the earliest tenants conducted a mixture of commerce, crafts and skills. There were shops, studios, offices and workrooms for some two hundred traders, dealers and artisans. Housed within the upper galleries were more studious and scholarly tenancies, such as bookshops, sheet music shops, piano-sellers and piano-tuners, as well as the salons of private teachers of music, dancing, singing, elocution, painting, sculpting, drawing and dressmaking. There were also more decorous sports including a billiards saloon, a gymnasium for ladies and a table tennis hall.[1]

The building was heavily criticised in the early years of its operation due to its poor financial return. Original real estate advice indicated the building could pay for itself from rents received, within thirty years. The first few years were slow. In 1898 only 47 out of about 200 available spaces were tenanted. This improved by the following year with another 20 tenants joining the list. By 1905, there were 150 tenants, but it was not until 1917 that the building was reaching its maximum tenancy rate. Up until that time there was a continual shortfall between the costs to Council and the rents received and Council was constantly looking at ways of improving its return.[1]

Early-20th-century alterations

As early as 1902, the City Council was worrying about the building being a "non-paying asset and handicap".[17] In ensuing years various schemes for selling, remodelling and/or demolition were proposed[18] and reports produced.[19] The markets originally held in the building were relocated to Haymarket in 1910. In 1912 it was described as an "incubus"[20] and in 1915 and 1916 as a "municipal 'white elephant'".[21][22] In 1913 a "decision to re-model was arrived at by 10 votes to 9" over the options to demolish or sell.[23] Although it had been accepted that nothing could be done until after the war,[21] in 1917 the council accepted a tender for alterations to the building.[24]

Your domes dream of Constantinople;

Facade picturesque;

Stained glass that glowed like an opal.

Sydney Romanesque.

They built you way back in the Boom Time,

The opulent era;

But now in the Seventies' Doom Time.

The wrecker stands nearer.

The noose of 'Progress' slowly throttles

The old and the brave,

New towers rise like giant jumbo bottles

Of cheap after shave.

How we hate all that sandstone as golden

As obsolete guineas,

With nowhere to stable our Holden,

Or tether our Minis.

A car park, a bank or urinal,

Would grace such a site;

The end could be painless and final,

The deed done by night.

Reactionary ratbags won't budge us,

Nor sentiment sway;

How will posterity judge us,

Ten years from today?

Barry Humphries (1971)[2]: page:94

A remodelling scheme was finally adopted by Council in May 1917. McLeod Brothers were awarded the contract for the work in June 1917 at a cost of £40,944. The following alterations were undertaken:[1]

- Removal of posted awning and replacement with a modern cantilevered awning with a lined soffit.

- Removal of the internal arcade on the ground floor producing shops running continuously from George to York Street.

- The gallery space was extended on the first floor reducing the void space and the remaining void covered over with a coloured leadlight ceiling (indicated on the drawings as lanterns) so that some light was available to the centre of the ground floor shops.

- The tiled floor was covered with concrete and timber obliterating the circular pavement lights.

- Removal of the entrance from Druitt Street to create one large shop with frontages to three streets.

- A new entrance was cut into the York Street side, to provide an entrance to the stairs and lift at the Druitt Street end of the building.

- New shopfronts were provided to the George Street facade. This work involved boxing in the trachyte columns behind showcases. The line of the shopfronts was extended out past the line of columns and a new marble and plate glass shopfront installed. Leaded glass panels were installed above the transom line, below the awning. The original coloured glass highlight panels were removed and clear glass panels in steel frames installed. The stall-board lights under the shopfronts were also removed, but some new pavement lights were installed to compensate.

- The original timber and glass shopfronts along George Street were re-erected to the shops in York Street providing additional street entrances from York Street, as the market activity in the basement no longer continued.

- New bathroom facilities were provided on a new mezzanine level along York Street.

- One passenger lift in the southern lift core was cut out and a new stair to the basement level installed.

- One lift in the northern stair lobby was cut out and the lift removed.

- A new goods lift was inserted near the central entrance on the York Street side.

- The void space under the central dome was infilled with a new passenger lift.

- Two of the cart lifts to the basement along York Street were removed and the resultant space formed into shops

- The galleries on the first and second floors were cantilevered seven feet out into the void space and the shopfronts moved forward seven feet to increase the available floor space in the tenancies.

- The first floor void area above the entrance at the Druitt Street entrance was formed into a room by inserting a new floor.

- The small passage serving the rooms along the first and second floor, at the Druitt Street end was removed increasing the floor space.

- The existing Concert Hall with a height of 42 feet was remodelled with two new floors inserted into the grand space providing three levels to provide space for the city library.[1]

These alterations in the name of economy and increased floor space destroyed much of the magnificent interior spaces and character of the building. The ground floor arcade was obliterated, the light quality in the basement reduced, the southern entry devalued and the internal voids and galleries reduced and devalued. The alterations were undertaken to remove what Council saw as, "inherent flaws", in what its Victorian creators considered, an architectural triumph. One of the disturbing aspects of these radical alterations was that now that the building's internal character had been violated and devalued, there was little resistance to further alterations.[1]

The building continued to incur losses and by 1933 the accumulated debt was announced as £500,000. No major alterations occurred between 1918 and 1934, but many small alterations to the individual shops such as new partitions, fitouts, and mezzanines were continually taking place. By the mid-1930s the depression was receding, employment growing, building and business reviving. Time had come to rework the building to further reduce the debt and hopefully return a profit. The council decided to move the rapidly expanding Electricity Department out of the Town Hall and relocate it in the QVB. In December 1933, Council voted to approve a major proposal to alter the Queen Victoria Building to suit the requirements of the Electricity Department. Approval was also given to invite tenders for the work. The majority of the work was confined to the central and northern section of the building. Essentially this scheme was to convert the interior to a general office space and install floors in what remained of the Grand Victorian internal spaces. The work costing (Pounds)125,000 was completed by 1935 and included the following changes:[1]

- Shopfronts along George Street were removed and replaced with a new Art Deco facade with "stay bright" steel mouldings, plate glass windows and black glass facing panels.

- To the York Street facade, new plate glass shopfronts were added with terra cotta tiles over the trachyte columns and remaining areas.

- A new Art Deco fascia and soffit to the cantilevered awning along George Street.

- The passenger lift was removed from the central void under the main dome and the floor infilled to create more floor space and a counter.

- Removal of the glass inner dome under the main dome and infilling with a new concrete floor to provide space for a new air conditioning plant.

- Removal of both of the grand staircases below the central dome to provide a central vestibule, air conditioning plant and locker rooms.

- Infilling of the void to the first floor, northern end, to provide additional floor space.

- Installation of a suspended ceiling under the main glass roof and cladding the glass roof with corrugated iron.

- The existing ground floor level was altered by inserting a new reinforced concrete floor over the existing with a series of steps to provide a level floor addressing each street level.

- Almost all decorative elements, features and mouldings were removed from the interior.

- New suspended ceilings and lighting to all other office spaces with ducted air conditioning services supplied.

- Removal of some of the spiral staircases.[1]

Many of the shops at ground floor level in the southern part of the building were retained although they received new shopfronts in line with the updated Art Deco image. The library in the northern area was retained with no new major alterations. The basement was subject to various alterations such as new concrete stairs, timber framed mezzanines and some new plant equipment, but the long term tenants remained in the basement ensuring little need for alterations.[1]

These extensive alterations attracted little public comment at the time. They were accepted within the name of progress as a necessary solution. It is fortunate that the majority of the facade fabric was not altered above the awning line. Perhaps the strength of the architectural image was too strong even for the most practical minded official. An enduring quality the building has always retained is in its ability to change without losing its external imagery and architectural strength as an element in the city. Up until the early 1970s the building became the home of the SCC and much of its identity in the city was based on this use even though the external envelope had not changed.[1]

Decay and debate

.jpg.webp)

Between 1934 and 1938 the areas occupied by the Sydney County Council were remodeled in an Art Deco style.[25] The building steadily deteriorated and in 1959 was again threatened with demolition.[2]: pages:80–94 Proposals to replace the building which many saw as "overdue for demolition" included ones for a fountain, a plaza and a car park.[2]: page:80 The occupancy by the SCC did however provide some security for the building by providing a constant income base. The SCC undertook continual changes to the building, some being significant alterations but the majority were minor such as new partitions, showrooms and fitouts. For example, in the thirty years between 1936 and 1966 a total of 79 separate building applications were lodged with the City Council by the SCC. There is little evidence that any of this work, which was basically related to functional uses and the needs of occupants, proceeded with any concern for the architectural strengths of the building.[1]

Proposals for demolition of the building gained strength by the late 1950s in a city eager to modernise and grow rapidly. The post war boom was in full swing and business confidence high. In 1959, Lord Mayor Jensen suggested a scheme demolishing the QVB and replacing it with a public square. Revenue from a badly needed underground carpark would pay for the demolition of the QVB and construction of the square. This scheme gained much support both from the public and the design professions in general. Jensen further suggested an international design competition similar to the competition for the Opera House site and won much support for the idea.[1]

Demolition proposals at the time were largely postponed by the continued presence of the SCC in the building. The SCC required another long lease which was granted by the City Council in 1961. The SCC was planning a new large building opposite town hall and required the existing facilities in the QVB to be retained until its completion. The City Council was in no position to refuse the SCC and thus the demolition proposals were temporarily thwarted, although opinion was always behind demolition and a reuse of the site at the time. A form of demolition actually started in 1963 with removal of the cupolas on the roof. Concern about their stability was given as the reason for their removal. The contractor paid for their removal, in fact made a larger profit out of the sale of the salvaged cupolas as souvenirs and garden decorations, than for the contract to remove them. As the new SCC building was nearing completion the question of the QVB's ultimate fate was approaching again. The debates in the late 1950s and early 1960s were largely deflated by the continued occupation of the SCC and other long term tenants, but, as this was not an issue any more, the debate was to enter another stage.[1]

By 1967 calls for its preservation were being made by the National Trust of Australia declaring it should be saved because of its historical importance. Calls were also made not only for its preservation but also for its restoration by stripping away the numerous disfigurements, restoring the glass vaulted roof, ground floor arcades, tiled floors, and stone stairs. Many schemes were promoted such as linking the building by tunnels to the Town Hall and other city buildings, schemes involving constructing nightclubs or planetariums under the dome, with shops on the lower levels, art galleries, hotel rooms etc. on the upper levels. Although these plans would have to wait, the council actually spent considerable funds on renovating the City Library.[1]

Demolition was still the favoured option by many in the council. Even as late as 1969 the Labor Party candidate running for mayor in the City Council elections stated that, if elected he would propose demolition of the QVB, which he said was "a firetrap to make way for a new civic square". The debate extended from whether or not the building should be demolished to what uses it could be made to serve if preserved and a campaign to preserve it ensued, supported by "public meetings, letters to editors, the National Trust and the Royal Australian Institute of Architects (NSW)[2]: page:18 as well as a group called the "Friends of the Queen Victoria Building".[26] On 31 May 1971, the Lord Mayor of Sydney, Alderman Emmet McDermott, leader of the Civic Reform Group, announced the building would be "preserved and restored to its original state".[2]: page:92 In 1974, it was classified by the National Trust,[4] which gave it an "A" classification and defined it as "urgently in need of acquisition and preservation".[2]: page:90 There was no suggestion of how that was going to take place, but such a statement became very much the turning point in the buildings history and eventual fate. The building was to be saved, but there was no plan or suggestions about where the funds were to come from. In 1979 the Town Clerk, Leon Carter stated; "The Council is determined that the high cost of rebirth of the QVB will not fall on the blistered shoulders of the weary ratepayer". Restoration proposals were held up by a combination of lack of funds and continuing disagreements between Council, potential operators and stakeholders such as the National Trust and the Royal Australian Institute of Architects.[1]

In February 1978, the Hilton bombing damaged the glass in QVB which led to its replacement in 1979. Finally in 1979 a team was established between Architects Stephenson & Turner and Rice Daubney, Engineers Meinhardt and Partners, Kuttner Collins & Partners for administration, with financial backing by IPOH Garden Berhad. Key conservation groups backed the plan. Negotiations about plans and leases continued for almost three years, but eventually on 1 August 1983 the Lord Mayor and IPOH Garden, signed a ninety-nine year profit-sharing lease.[1]

Late-20th-century restoration

.jpg.webp)

The Queen Victoria Building was restored between 1984 and 1986 by the Malaysian Company, Ipoh Ltd (now owned by the Government Investment Corporation of Singapore), at a cost of $86 million, under the terms of a 99-year lease from the City Council and now contains mostly upmarket boutiques and "brand-name" shops.[27] During the restoration a car park station was built under York Street. The building's restoration retained its exemplary features including the trachyte stairs, tessellated tiled surfaces and column capitals and created a commercial establishment that houses high end fashion stores, cafés, and restaurants which reflect the original purpose of the building in the city of Sydney.[11]

"If there is a lesson for heritage projects from this, it is that heritage buildings should not only be restored but should be put to a use that will make them freely accessible to the community at all times ..."Yap Lim Sen (Chairman, Ipoh Ltd Australia)[28]

The building reopened at the end of 1986 in time to catch the busy Christmas trading season. The work took almost four years to complete and included a new underground carpark, linking tunnels and a restored interior. As almost nothing of the original interior fabric was left intact the work largely involved reconstructing the details and atmosphere of the place. The completed project can be considered a sound commercial scheme, but not a true reconstruction. A museum approach to conserving the building was recognised by all authorities as being unworkable as the building would be empty and devoid of the life the restoration brief considered essential.[1]

21st-century renovations

By 2006, after successfully trading for twenty years, comprehensive plans were being prepared to conserve the exterior and refurbish the interior of the building to ensure the place was commercially viable as an ongoing retail complex. The major upgrade of the building's interiors were designed by the architectural firm Ancher Mortlock and Woolley in association with interior design firm Freeman Rembel and included installation of:[1]

- Contemporary shopfronts, interior signage, a new internal colour scheme, new internal lighting, BCA compliant glass and metal balustrades, new floor finishes, reconstruction of ground floor steel entrance gates and selective bathroom upgrades.

- A new vertical escalator system in both the north and south galleries.[1]

Between 2008 and 2009, Ipoh performed a $48 million refurbishment[25] adding new colour schemes and shopfronts, glass signage, glazed balustrades and escalators connecting ground, first and second levels.[29] This renovation was described by one architecture critic as an example of Sydney's tendency to "start with something wonderful then, with enormous care and expense, wreck it."[30] The recent conservation and refurbishment approach has aimed to clarify the legibility between historic fabric and the new fabric which must be continually updated to ensure the building is viable as an ongoing commercial complex. After its successful refurbishment, the QVB was officially reopened by the Lord Mayor of Sydney Clover Moore on 25 August 2009.[1][31]

Description

A landmark grand Victorian retail arcade of three storeys, with sandstone clad walls and copper domes, designed in the Federation Romanesque style, dating from 1893 to 1898. Apart from the ground floor the facade is basically unaltered, being composite Romanesque and Byzantine style on a grand scale to a large city block. Constructed of brickwork and concrete with steel roof structure and the exterior faced in Sydney freestone. The dominant feature is the great central dome of 19 metres (62 ft) in diameter and 60 metres (196 ft) from ground to top of cupola and is sheeted externally in copper, as are the 20 smaller domes. The building consists of basement, ground and two main upper floors with additional levels in the end pavilions.[1]

Interior

The building consists of four main shopping floors. The top three levels have large openings (protected by decorative cast-iron railings) that allow natural light from the ceiling to illuminate the lower floors. Much of the tilework, especially under the central dome, is original, and the remainder is in keeping with the original style. Underground arcades lead south to Town Hall railway station and north to the Myer building.

The upper level is especially spacious at the northern and southern ends of the building. The northern end was previously the Grand Ballroom, and is today a tea room.

Displays

Two mechanical clocks, each one featuring dioramas and moving figures from moments in history, can be seen from the adjacent railed walkways. The Royal Clock activates on the hour and displays six scenes of English royalty accompanied by Jeremiah Clarke's trumpet voluntary. The Great Australian Clock, designed and made by Chris Cook, weighs four tonnes (four short tons) and stands ten metres (thirty-three feet) tall. It includes 33 scenes from Australian history, seen from both Aboriginal and European perspectives. An Aboriginal hunter circles the exterior of the clock continuously, representing the never-ending passage of time.

The building also contains many memorials and historic displays. Of these, two large glass cases, removed in 2009–10, stood out. The first display case contained an Imperial Chinese Bridal Carriage made entirely of jade and weighing over two tonnes, the only example found outside China. The second was a life-sized figure of Queen Victoria in a replica of her Coronation regalia, and surrounded by replicas of the British Crown Jewels. Her enthroned figure rotated slowly throughout the day, fixing the onlooker with a serene and youthful gaze. The regalia is now on display at the Museum of Australian Democracy.

On the top level near the dome is displayed a sealed letter to be opened in 2085 by the future Lord Mayor of Sydney and read aloud to the People of Sydney. It was written by Queen Elizabeth II in 1986 and no one else knows what it contains.

Statuary

Two allegorical groups of marble figures above the entrances on York Street and George Street (the two long sides of the building) were designed by William Priestly MacIntosh and selected by a committee made up of the Mayor (Alderman Ives), the Government Architect (Walter Liberty Vernon) and the city Architect (McRae) from designs submitted and displayed in the Sydney Town Hall,[32] among which was one submitted by Australia's first locally-born woman sculptor, Theodora Cowan.[33] MacIntosh's two winning allegorical groups consisted of one centring on a figure of the "Genius of the City" and the other on the "Genius of Civilisation", who was said to be modelled on Australian swimmer Percy Cavill.[34] They were described thus:[32]

George Street group Standing upon a raised pedestal in the centre is a female figure lightly draped in flowing robes, representing the "Guardian Genius of the City", with the symbol of Wisdom in one hand and Justice in the other. She is crowned with the civic crown and waratah wreath. At her feet is a shield bearing the city crest. On her right is seated a semi-nude, muscular, male figure, representing Labor and Industry, with the appropriate symbols, viz., wheat, a ram, fruit, and a beehive, grouped round him. On her left is a corresponding male figure representing Commerce and Exchange. A ship in full sail is shown on his left. A bag of money is in one of his hands, and the ledger book in the other. Both figures are wreathed with olive, the symbol of Peace.

York Street group The central figure, a vigorous youth representing civilisation holds aloft the torch to better guide science and the arts and crafts represented by two beautiful semi-nude girls. Science has a compass and is checking some facts stated on a scroll she holds in her left hand. She is in deep thought in fine contrast to her sister representing Arts And Crafts who is looking with a welcoming and pleading look ...[35]

The statuary for the second group was approved in February 1898.[36] Mr McRae was "well satisfied" with the decision, although he would have preferred them to have been made in bronze.[32]

Bicentennial Plaza

At the southern end of the building is the Bicentennial Plaza, facing the Sydney Town Hall across Druitt Street. Another statue of Queen Victoria, arrayed on a light grey stone plinth, is the work of Irish sculptor John Hughes. This statue stood outside the legislative assembly of the Republic of Ireland—Dáil Éireann in Leinster House, Dublin—until 1947, when it was put into storage. It was later given to the people of Sydney by the Government of the Republic of Ireland and placed on its present site in 1987.[37]

Nearby stands a wishing well featuring a bronze sculpture of Queen Victoria's favourite dog "Islay", which was sculpted by local Sydney artist Justin Robson. A recorded message voiced by John Laws urges onlookers to give a donation and make a wish. The money cast into this well goes to the benefit of deaf and blind children.

Condition

.jpg.webp)

As at 16 February 2004, the exterior facades above the awning line are largely intact but heavily conserved. For example, the drum of the dome is of rendered concrete painted to resemble stone and the small cupolas adorning the parapet are of fibre glass construction painted to resemble copper. Below the awnings, shopfronts have been interpretively reconstructed. Externally, the building is in good condition.[1]

Internally some historic fabric remains. However, due to wide scale destruction in the past the interiors, which were constructed between 1982 and 1986, are largely an interpretive reconstruction as opposed to an accurate reconstruction. While some original features and fabric remains, the 1986 "restoration" approach intended to recreate the imagery of a grand Victorian style arcade with considerable concessions made to ensure the place was commercially viable as a retail shopping centre.[1]

The interior has been modified with the installation of contemporary shopfronts, new interior signage, a new contemporary internal colour scheme, new internal lighting, BCA compliant glass and metal balustrades, new floor finishes, reconstruction of ground floor steel entrance gates and selective bathroom upgrades. The recent conservation and refurbishment approach has aimed to clarify the legibility between historic fabric and new fabric. A new vertical escalator system in both the north and south galleries has also been installed. Internally, the building is in good condition.[1][31]

Modifications and dates

- 1893: Construction commences

- 1898: Opening of the building

- 1917: Major internal alterations including enclosing ground floor, reduction in void sizes, alterations to vertical transport systems and major increase in lettable floor spaces

- 1935: Major internal alterations as building is converted to Local Government office space and facilities with shops to external street frontages, removal of most internal decorative elements including glass domes, Art Deco facade added to George Street

- 1982–1986: Major conservation and refurbishment of building, returned to use as retail complex

- 2006–2009: Major internal conservation of facades and internal refurbishment including new colour scheme, new escalators to north and south void, new signage, balustrades, lighting and shopfronts.[1]

Heritage listing

The Queen Victoria Building was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 5 March 2010. It was noted as an outstanding example of the grand retail buildings from the Victorian-Federation era in Australia, which has no known equal in Australia in its architectural style, scale, level of detailing and craftsmanship.[1][38][39][16]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 "Queen Victoria Building". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H01814. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Shaw, John (1987). The Queen Victoria Building 1898–1986. Sydney, NSW, Australia: Wellington Lane Press. ISBN 0-646-35181-8.

- ↑ "Advance Australia Arms Queen Victoria Building, 1898". Environment & Heritage. Government of New South Wales. 1 September 2012.

- 1 2 Ellmoos, Leila (2008). "Queen Victoria Building". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust.

- ↑ Kapur, R.; Majumder, A. (2007). Bazaars Down Under. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan Pvt.Ltd. p. 16. ISBN 978-81-7991-259-1.

- ↑ "George McRae". Sydney Architecture. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ↑ O'Gorman, J. F. (1991). Three American Architects: Richardson, Sullivan, and Wright, 1865–1915. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-226-62072-7.

- 1 2 "Action by the City Council". The Sydney Morning Herald. 10 June 1897. p. 5. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ↑ "Important building operations in Sydney". Australian Town and Country Journal. NSW. 12 January 1895. p. 25. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ↑ "Queen Victoria Market Buildings". The Sydney Morning Herald. 15 June 1898. p. 5. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- 1 2 "About QVB". QVB. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ↑ "Ball at the Town Hall". The Sydney Morning Herald. 22 July 1898. p. 3. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ↑ Rutledge, Martha. "Harris, Sir Matthew (1841–1917)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- 1 2 "The Queen Victoria Markets". The Sydney Morning Herald. 22 July 1898. p. 3. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ↑ "Town". Australian Town and Country Journal. NSW. 3 June 1899. p. 14. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- 1 2 National Trust of Australia

- ↑ "The Queen Victoria Markets". The Sydney Morning Herald. 18 September 1902. p. 6. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ↑ "Queen Victoria Markets". The Evening News. Sydney. 1 May 1908. p. 4. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ↑ "Queen Victoria Markets". The Evening News. Sydney. 13 January 1910. p. 4. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ↑ "Queen Victoria Markets". The Sydney Morning Herald. 31 August 1912. p. 14. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- 1 2 "Queen Victoria Markets". The Sydney Morning Herald. 23 February 1915. p. 7. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ↑ "Queen Victoria Markets". Moree Gwydir Examiner and General Advertiser. NSW. 24 March 1916. p. 2. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ↑ "Queen Victoria Markets alterations". The Evening News. Sydney. 3 December 1913. p. 14. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ↑ "Queen Victoria Markets". Construction and Local Government Journal. NSW. 26 June 1917. p. 9. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- 1 2 "History of QVB". QVB. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ↑ The Newsletter of the group is held in the National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Store map". QVB. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ↑ Stirling, Suzanne; Ivory, Helen (1998). QVB – An Improbable Story. Sydney, NSW, Australia: Ipoh Ltd. ISBN 0-908022-06-9.

- ↑ "QVB". Ipoh. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ↑ Farrelly, Elizabeth (13 August 2009). "Babylonian fantasy land emerges from reservoir". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- 1 2 Graham Brooks & Associates, 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Statuary for Sydney Markets". Australian Town and Country Journal. Sydney. 15 May 1897. p. 30. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ↑ Sturgeon, Graeme (1978). The Development of Australian Sculpture 1788–1975. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 48.

- ↑ Earnshaw, Beverley (2004). An Australian Sculptor: William Priestly Macintosh. Kogarah: Kogarah Historical Society. p. 47. ISBN 095939253X.

- ↑ Scarlett, Ken (1980). Australian sculptors, 1830–1977. West Melbourne, Victoria: Thomas Nelson (Australia). p. 400. ISBN 0170052923.

- ↑ "City Council". The Sydney Morning Herald. 11 February 1898. p. 2. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ Fallon, Donal. "Story of the statue in front of Sydney's Queen Victoria Building". Inside History. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ↑ Sydney Council Council

- ↑ Graham Brooks and Associates, 2003.

Bibliography

- Balint, E.; UNSW School of Building (1984). Historic Record of Sydney City Buildings.

- City of Sydney. State Heritage Inventory form for Queen Victoria Building.

- Council of the City of Sydney (1979) Queen Victoria Building: restoration brief. Sydney, NSW: The Council

- Gamble, Allan (1988) The Queen Victoria Building: a sketch portrait. Seaforth, NSW: Craftsman House, ISBN 0947131124

- Graham Brooks & Associates (2009). QueenVictoria Building, Sydney, NSW : archival recording stage 2.

- Graham Brooks and Associates (2003). Conservation Management Plan – Queen Victoria Building.

- Graham, S. J. (2008) Victor Turner and Contemporary Cultural Performance. Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781845454623

- Ipoh Garden (Aust) Pty Ltd. (1986) The Queen Victoria Building: restoration. Sydney, NSW: John Fairfax & Sons

- Jonathan Bryant, Graham Brooks and Associates (GBA) (2009). Queen Victoria Building Heritage Database Suggested Amendments.

- Macmahon, B. (2001) The Architecture of East Australia. London: Edition Axel Menges ISBN 3930698900

- National Trust of Australia (NSW). National Trust City Register.

- O'Brien, Geraldine (2003). Dowager to vamp in a dash of bold colour (SMH 19 December 2003).

- Sheedy, D.; National Trust of Australia (NSW) (1974). Queen Victoria Building Classification Card.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article contains material from Queen Victoria Building, entry number 1814 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 14 October 2018.

This Wikipedia article contains material from Queen Victoria Building, entry number 1814 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 14 October 2018.

_(cropped).jpg.webp)