| Part of a series on |

| Kabbalah |

|---|

|

In the Zohar, Lurianic Kabbalah, and Hermetic Qabalah, the qlippoth (Hebrew: קְלִיפּוֹת, romanized: qəlippoṯ, originally Jewish Babylonian Aramaic: קְלִיפִּין, romanized: qəlippin, plural of קְלִפָּה qəlippā; literally "peels", "shells", or "husks"), are the representation of evil or impure spiritual forces in Jewish mysticism, the opposites of the Sefirot.[1][2] The realm of evil is called Sitra Achra (Jewish Babylonian Aramaic: סִטְרָא אַחְרָא, romanized: siṭrā ʾaḥrā, lit. 'The Other Side') in Kabbalistic texts.

In the Zohar

The qlippoth are first mentioned in the Zohar, where they are described as being created by God to function as a nutshell for holiness.[3] The text subsequently relays an esoteric interpretation of the text of Genesis creation narrative in Genesis 1:14, which describes God creating the moon and sun to act as "luminaries" in the sky. The verse uses a defective spelling of the Hebrew word for "luminaries", resulting in a written form identical to the Hebrew word for "curses". In the context of the Zohar, interpreting the verse as calling the moon and sun "curses" is given mystic significance, personified by a description of the moon descending into the realm of Beri'ah, where it began to belittle itself and dim its own light, both physically and spiritually. The resulting darkness gave birth to the qlippoth.[4] Reflecting this, they are thenceforth generally synonymous with "darkness" itself.[5][6]

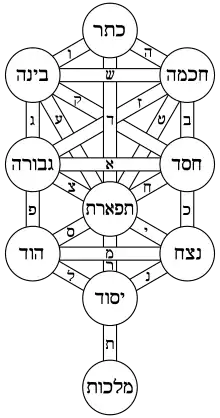

Later, the Zohar gives specific names to some of the qlippot, relaying them as counterparts to certain sephirot: Mashchith (Hebrew: מַשְׁחִית, romanized: mašḥīṯ, lit. 'destroyer') to Chesed, Af (Hebrew: אַף, romanized: ʾap̄, lit. 'anger') to Gevurah, and Hema (Hebrew: חֵמָה, romanized: ḥēmā, lit. 'wrath') to Tiferet.[7] It also names Avon (Hebrew: עָוֹן, romanized: ʿāvōn, lit. 'iniquity'),[8] Tohu (Hebrew: תֹהוּ, romanized: tōhū, lit. 'formless'), Bohu (Hebrew: בֹהוּ, romanized: bōhū, lit. 'void'), Esh (Hebrew: אֵשׁ, romanized: ʿēš, lit. 'fire'), and Tehom (Hebrew: תְּהוֹם, romanized: təhōm, lit. 'deep'),[9] but does not relate them to any corresponding sefira. Though the Zohar clarifies that each of the sefirot and qlippoth are 1:1, even down to having equivalent partzufim, it does not give all of their names.

In Lurianic Kabbalah

In the Kabbalistic cosmology of Isaac Luria, the qlippoth are metaphorical "shells" or "peels" surrounding the sefirot. They are the innate spiritual obstacles to holiness and receive their existence from God only in an external and circumstantial manner, rather than an internal and direct manner. In this sense, qlippoth have a slightly beneficial function, as much like a peel protects a fruit, so do the qlippoth technically prevent the flow of Divinity (revelation of God's true unity) from being dissipated as it permeates throughout the various facets of Creation. Nevertheless, as a consequence, the qlippoth conceal this holiness, and are therefore synonymous with what runs counter to Jewish thought, like idolatry, impurity, rejection of Divine unity (dualism), and with the Sitra Achra, the perceived realm opposite to holiness. Much like their holy counterparts, qlippoth emerge in a descending seder hishtalshelus "Chain of Being" through Tzimtzum (God's action of contracting Ohr Ein Sof, "infinite light", to provide a space for Creation).

Kabbalah distinguishes between two realms in qlippot, three completely impure qlippoth (Hebrew: הַטְמֵאוֹת, romanized: haṭmēʾoṯ, lit. 'the unclean [ones]') and the remainder of intermediate qlippoth (Hebrew: נוֹגַהּ, romanized: noḡah, lit. 'ligh'). The qlippoth nogah are "redeemable", and can be refined and sublimated, whereas the qlippoth hatme'ot can only be redeemed by their destruction.

Similar to a certain interpretation of the Kabbalistic tree of life, the qlippoth are sometimes imagined as a series of concentric circles which surround not just aspects of God, but also one another. Their four concentric terms derived from various phrases used in the prophet Ezekiel's famous vision of the Throne of God in Ezekiel 1:4, itself the focus of a school of Jewish mystic thought called Merkabah mysticism. "I looked, and lo, a stormy wind came sweeping out of the north—a huge cloud and flashing fire, surrounded by a radiance; and in the center of it, in the center of the fire, a gleam as of amber." The stormy wind, huge cloud, and flashing fire are associated with the aforementioned three "impure" qlippoth, with the "brightness" associated with the "intermediate" qlippoth.

In medieval Kabbalah, it was believed that the Shekhinah (God's presence) is separated from the sefirot by man's sins, while in Lurianic Kabbalah it was believed the Shekhinah was exiled to the qlippoth due to the shattering of divinity into Tohu and Tikun, which is a natural part of its cosmological model of Creation. This, in turn, causes the sefirot's various partzufim or "visages" (from Koinē Greek: πρόσωπον, romanized: prósophon) to be exiled in the qlippoth as well, thereby causing these qlippoth to manifest as either the qlippoth nogah or hatme'ot. From there, the qlippoth nogah would be redeemed through the observance of the 613 commandments. The qlippoth hatme'ot would be indirectly redeemed through the negative commandments, which merely require abstention from an act.

In addition to righteous living, genuine repentance also allows the qlippoth to be redeemed, as it retrospectively turns sin into virtue and darkness into light, and thus deprives the qlippoth of their vitality. According to Lurianic doctrine, when all the partzufim are freed from the qlippoth, the Messianic Age will begin.

In Hasidic philosophy, which is underlined by panentheistic and monistic thought, the qlippoth are viewed as a representation of the ultimately acosmistic self-awareness of Creation. The Kabbalistic scheme of qlippoth is internalized as a psychological exercise, by focusing on the self, opposite to devekut, or the practice of "self-nullification" to better grasp mystic contemplation.

Hermetic Qabalah magical views

In some non-Jewish Hermetic Qabalah, contact is sought with the qlippoth, unlike in Judaism, as part of its process of human self-knowledge. In contrast, the theurgic Jewish practical Kabbalah was understood by its practitioners as similar to white magic, accessing only holiness, while the danger inherent in such ventures involving the intermingling of holiness and impure magic ensured that accessing the Qlipoth remained a minor and restricted practice in Jewish history.

Mathers' interpretation

Christian Knorr von Rosenroth's Latin Kabbala denudata (1684) (translated The Kabbalah Unveiled by Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers) equates these forces with the Kings of Edom and also offers the suggestion they are the result of an imbalance towards Gedulah, the Pillar of Mercy or the merciful aspect of God, and have since been destroyed.[10] In subsequent Hermetic teachings, the qlippoth have tended, much like the sefiroth, to be interpreted as mystical worlds or entities, and merged with ideas derived from demonology.

In most descriptions, there are seven divisions of Hell; Sheol or Tehom; Abaddon or Tzoah Rotachat; Be'er Shachat Hebrew: בְּאֵר שַׁחַת, lit. 'pit of corruption' or Mashchit; Bor Shaon (Hebrew: בּוֹר שָׁאוֹן, lit. 'cistern of sound') or Tit ha-Yaven (Hebrew: טִיט הַיָוֵן, lit. 'clinging mud'); Dumah or Sha'are Mavet (Hebrew: שַׁעֲרֵי מָוֶת, lit. 'gates of death'); Neshiyyah (Hebrew: נְשִׁיָּה, lit. 'oblivion, "Limbo"') or Tzalmavet; and Eretz Tachtit (Hebrew: אֶרֶץ תַּחְתִּית, lit. 'lowest earth, Gehenna'),[11][12][13][14] twelve qlippothic orders of demons, three powers before Satan, and twenty-two demons which correspond to the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet.

Crowley and Regardie

According to Aleister Crowley, the three evil forms (before Samael), are said to be Qemetial, Belial, and Othiel.[15]

Crowley (who calls them "Orders of Qliphoth")[16] and Israel Regardie[17] list the qlippoth as Thaumiel, Ghogiel, Satariel, Agshekeloh, Golohab, Tagiriron, Gharab Tzerek, Samael, Gamaliel, and Lilith.

Kenneth Grant

Kenneth Grant suggested Lovecraft's description of Yog-Sothoth as a conglomeration of "malignant globes" may have been inspired by the qlippoth.[18]

See also

References

- ↑ Mathers (1887), "The Book of Concealed Mystery".

- ↑ Franck (1926), p. 279.

- ↑ "Zohar". www.sefaria.org.

- ↑ "Zohar, Bereshit 9:110". www.sefaria.org.

When the moon was united with the sun, the moon had its own light. But after the moon was separated from the sun, it descended to the world of Briyah and was placed in charge of the hosts of Briyah, it belittled itself and diminished its own light. So Kelipot upon Kelipot were created, one above the other, to conceal the inner part. All this occurred to complete the light of the inner part, because without a shell no fruit can be had. This is the reason why it is written: "Let there be luminaries (מְאֹרֹת)," without Vav, which means a curse, because of the Kelipot that emerge due to the diminution of the light of the moon. All this was done for the perfection of the world. Therefore, it is written: "To give light upon the earth" (Gen. 1:15), as these Kelipot emerged in the secret of the shell that precedes the fruit.

- ↑ "Zohar 2:115b". Archived from the original on 2021-10-10. Retrieved 2021-10-10.

- ↑ "Full Zohar Online - Mishpatim - Chapter 10". www.zohar.com.

- ↑ "Zohar 3:279b". Archived from the original on 2021-10-10. Retrieved 2021-10-10.

- ↑ Zohar Chadash, Tikuna Kadma'ah 31, Sefaria

- ↑ "Zohar 3:227a". Archived from the original on 2021-10-10. Retrieved 2021-10-10.

- ↑ Mathers (1887), "Greater Holy Assembly", Chapter XXVI: Concerning the Edomite Kings.

- ↑ Boustan & Reed (2004), p. .

- ↑ Mew (1903), p. .

- ↑ Lowy (1888), p. 339.

- ↑ Pusey (1881), p. 102.

- ↑ Crowley (1986), p. .

- ↑ Crowley (1986), p. 2, Table VIII.

- ↑ Regardie (1970), p. 82, "Fifth knowledge lecture".

- ↑ Harms & Gonce (1998), p. 109.

Works cited

- Boustan, Ra'anan S.; Reed, Annette Yoshiko, eds. (2004). Heavenly Realms and Earthly Realities in Late Antique Religions. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139453981.

- Crowley, Aleister (1986). 777 and Other Qabalistic Writings of Aleister Crowley. Weiser Books. ISBN 0-87728-670-1.

- Franck, Adolphe (1926). "Relation of the Kabbalah to Christianity". The Kabbalah: Or, The Religious Philosophy of the Hebrews. Translated by I. Sossnitz. New York: Kabbalah Publishing Company.

- Harms, Daniel; Gonce, John Wisdom (1998). The Necronomicon Files. York Beach, Maine: Red Wheel/Weiser. ISBN 1578632692.

- Lowy, A. (1888). Old Jewish Legends of Biblical Topics: Legendary Description of Hell. Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology. Vol. 10.

- Mathers, S. L. MacGregor (1887). The Kabbalah Unveiled. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

- Mew, James (1903). Traditional Aspects of Hell: (Ancient and Modern). S. Sonnenschein & Company Lim.

- Pusey, Edward Bouverie (1881). What is of Faith as to Everlasting Punishment: In Reply to Dr. Farrar's Challenge in His 'Eternal Hope', 1879. James Parker & Co.

- Regardie, Israel (1970). The Golden Dawn. Llewellyn Worldwide. ISBN 0-87542-663-8.

Further reading

- Dan, Joseph, ed. (1986). The Early Kabbalah. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0809127696.

- Fries, Jan (2012). Nightshades: A Tourist Guide to the Nightside. Oxford: Mandrake of Oxford. ISBN 978-1906958459.

- Grant, Kenneth (1977). Nightside of Eden. London: Frederick Muller Limited. ISBN 0-584-10206-2.

- Grant, Kenneth (1994). Cults of the Shadow. Skoob. ISBN 978-1871438673.

- Rees, I. (2022). The Tree of Life and Death: Transforming the Qliphoth. Aeon Books Limited. ISBN 978-1801520065.

- Scholem, Gershom (1974). Kabbalah. Quadrangle/New York Times Book Company. ISBN 978-0812903522.