| Juren | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Wei Yuan, a Qing dynasty juren scholar | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 舉人 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 举人 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | recommended man | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

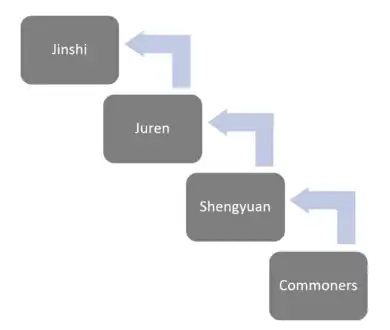

Juren (Chinese: 舉人; lit. 'recommended man') was a rank achieved by people who passed the xiangshi (Chinese: 鄉試) exam in the imperial examination system of imperial China.[1] The xiangshi is also known, in English, as the provincial examination.[1] It was a rank higher than the shengyuan rank, but lower than the jinshi rank, which was the highest degree.[2]

To achieve the juren rank, candidates, who had to already hold the shengyuan rank, had to pass the provincial qualifying examination, held every three years in the provincial capital.[2] A second, less widespread pathway to gaining the juren rank was through office purchase.[3]

Those with the juren rank gained gentry status and experienced social, political and economic privileges accordingly.[4]

The juren title was also awarded in the military examination system in imperial China.[3]

History

The term juren was first used in the Han Dynasty to refer to individuals at the provincial level who were recommended for civil service.[5] Those who were recommended for civil service were required to pass a central government examination before they were awarded an official title.[6]

The civil service examination system was first officially established in the Sui dynasty.[3] During the Sui, Tang, and Song dynasties, juren was used to refer to candidates of the state examination.[5] During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the civil examination system matured and became well-established.[2] During these later dynasties, juren was the title awarded to candidates who had successfully passed the provincial examinations. The awarding of the juren title ended with the abolition of the civil examinations in 1904.[7]

Appointment

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, there were two pathways to gaining the juren rank: one, through the civil examination system; the other, through office purchase.[4]

Civil examination

The juren rank was awarded for candidates who passed the provincial level of the civil examination system in the Ming and Qing dynasties.[2] The juren who came first in the examination process was awarded the title of jieyuan (Chinese: 解元).[3] The qualifying exam was held in each provincial capital, once every three years.[2] Candidates were required to take the examination in their registered province and sitting the examination in unregistered provinces was prohibited.[8] This process was called the zhengtu (Chinese: 正途), or the regular path.[3]

The provincial examinations, called xiangshi (Chinese: 鄉試), were written exams which occurred in three stages.[9] Candidates were required to participate in all three stages of the examination.[10] A quota system at the provincial level controlled the number of juren titles awarded.[11] Obtaining the juren degree through the civil examination pathway was a difficult process, with competition notably increasing during the Ming dynasty.[12] By 1630, there were approximately 49200 candidates from across China competing for 1279 juren degrees, with only 2.6% of candidates successfully obtaining the degree.[12] From the period of 1800 to 1905, around 1500 men throughout China were awarded the juren degree after every provincial examination.[7]

The examination was open to men from all socio-economic backgrounds, as long as they were holders of the shengyuan degree, which was the degree directly below the juren degree in China’s imperial civil examination system.[2] There was no limit on a candidate’s age or on the number of times a candidate could sit the exam and candidates did not require a reference from officials to participate.[2][9] However, women, Buddhist and Daoist clergy, and merchants were excluded from participating.[13] It was only during the Ming dynasty when sons of merchants were first legally allowed to take any civil examination.[11]

The provincial examination occurred in the fall of every third year. Shengyuan degree holders were required to travel to their respective provincial capitals to take three written examinations which were conducted over a week. An Imperial Commissioner, also known as the Grand Examiner, was sent to overlook the examinations from Beijing, the capital of China at the time.[7]

The examination was governed by strict rules to ensure the process was fair. All essays were first transcribed in red ink before marking, to prevent examiners from identifying the candidates by their calligraphy and showing favourable treatment to particular candidates.[11][13] As many as eight examiners would grade one candidate’s exam, whose name was concealed.[14] Examiners would be removed from office if it was found that they had favoured a particular candidate during the grading of the exams.[14] During the period that the Imperial Commissioner was in the province to overlook the examinations, his residence was guarded to prevent any candidates or friends or family of candidates from approaching him.[13]

The provincial examination took place over three sessions with each session of the exam being held on a separate day.[3][13] Three days would pass between each day of examination.[3] The examination process started early in the day, Candidates assembled by the gates of the examination hall and candidates were allowed in enter the hall once their name was called.[13] Each candidate was given a roll of paper which identified the examination cell the candidate was to occupy in the exam. The examination hall was divided into long alleys lined with open cells, in which candidates took their exam.[13] At one time, there could be up to ten or twelve thousand individuals in the same examination hall, from day to night.[13]

Curriculum

Each of the three sessions of the provincial examination tested candidates on separate areas of the curriculum. During the Qing dynasty, the first session required candidates to answer three questions based on the Four Books and four questions on one of the Five Classics. The particular Classic on which the four questions were answered on was chosen by the candidate.[10] In the second session, the candidate was required to write a discussion of the Classic of Filial Piety. Additionally, the candidate was required to compose five essays on writing verdicts and attempt any one of the following political forms of writing: an address to the emperor, an imperial declaration, or another form of imperial decree.[10] In the third session, five essay questions on problems concerning the Five Classics, history and administrative affairs were to be answered.[10]

In addition to the content of the exam, form was an examinable aspect of the candidate’s submission. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, all candidates’ essays were required to be composed in the form of eight-legged essays, which was a form of prose-writing involving strict enforcement of rigid parallel-prose styles.[15] Candidates were rejected for writing in any structure which diverged from this standardised form.[10]

Throughout the use of the civil examination system, there were minor changes to the provincial examination format and curriculum. In 1663, the imperial examination banned writing in the eight-legged essay form;[10] however, the form was reintroduced in 1668.[10] In 1687, the imperial declaration and decree were removed as possible political forms of writing for candidates in the second session.[10] In 1758, the first session was changed to include a question on Song dynasty Neo-Confucian rationalist books.[10] In 1767, the first session was changed to consist of only three questions on the Four Books while the discussion on the Five Classics was moved to the second session. Writing verdicts and addresses to the emperor were also abolished. Instead, a poetry question was introduced.[10] In 1782, the question on poetry was moved to the first session and the question on Song Neo-Confucian rationalism was moved to the second session.[10] In 1787, the candidate’s option of choosing any one of the Five Classics to discuss in the exam was changed so that a particular book from the Five Classics was set for candidates to compulsorily answer. In the same year, the question on Neo-Confucian rationalism was removed from the syllabus.[10] By 1793, candidates were expected to write essays on all Five Classics.[10] After 1793, the syllabus of the provincial examination remained fixed.[10]

Office purchase

The second pathway to obtaining the juren degree was through office purchase.[3] Obtaining degrees through office purchase was known as the yitu (Chinese: 異途), or the irregular path to gaining a degree.[3] Office purchase, known as juanna (Chinese: 捐纳), was the practice of obtaining degrees and offices through purchase, instead of through successfully passing the civil examinations. The practice was formally introduced in the Ming dynasty and continued to exist through the Qing dynasty as a common practice.[4] This was a legal process and was overseen by the government.[4]

During the Qing dynasty, men could become officials by making a payment in silver to the government. Through office purchase, men did not need to meet any eligibility requirements to be appointed the juren rank. Those who obtained the juren degree through office purchase enjoyed the same benefits, privileges and opportunity for career advancement as those who obtained the degree through the civil examinations.[4] Men could register for the prefecture-level entrance examination and then purchase the juren degree.[7] It was also common for juren degree-holders to use office purchase to further their careers.[4]

Responsibilities and privileges

Obtaining the juren rank enabled degree-holders to obtain official positions. In the Tang dynasty, only jinshi degree-holders were eligible for official positions.[16] However, in the Ming and Qing dynasties, passing the provincial examination and obtaining the juren degree entitled the degree-holder to obtain a lower-level government official role.[16][2] In the early- and mid-Ming dynasty, juren served as prefecture, county, and department education officials.[12] This entitled them to act as provincial examination officials. Juren who had failed to obtain the jinshi degree were immediately eligible to become education officials and act as directors and subdirectors of prefectural and county schools.[17] In the late-Ming dynasty, juren were placed in posts of county magistrates, as well as directors and subdirectors of schools.[12][17] Those who were appointed magistrate were responsible for collecting taxes from the residents of their county. Additionally, magistrates were responsible for maintaining law, order, and the moral and ethical standards in the areas under their control.[18] However, by the end of the Ming dynasty and into the Qing dynasty, jinshi degree-holders had begun to displace juren degree-holders in high-level official positions.[12]

The juren rank brought degree-holders and their families such substantial privileges that it was not uncommon for families to pool their resources to support promising individuals from poor families during the examination process.[2] Only those awarded with the juren degree had the opportunity to obtain the highest degree of the civil examination system, the jinshi degree, through the national examination.[7] In the Qing dynasty, it became a requirement for candidates of the jinshi rank to have a father who had passed the provincial examination and had acquired at least a juren rank.[19] An additional benefit of the juren degree was that the title was awarded for life, unlike the lower prefectural shengyuan degree.[7] The juren degree could not be inherited.[2]

Aside from the possibility of gaining higher official roles, juren also gained a higher social status. In imperial China, examinations and merit were strongly associated with social status, wealth, prestige, and political power.[11] This is reflected in how juren were distinctly addressed as laoye ("your honour") by commoners.[17] Gaining the juren rank brought the degree-holder social privileges such as improved prospects for good marriages. Additionally, juren gave their family the ability to gain or maintain their elite status.[4][7] For example, juren degree-holders were eligible to erect flagpoles with red and gold silk flags at their residences to announce their achievements.[16] Their families were referred to as "flagpole families", which was an honour and symbolised the higher social status of the family.[20]

The legal privileges experienced by juren include exemption from labour services required of all commoners except civil examination degree-holders.[17] They were also exempt from normal penal codes and corporal punishment, and could not be arrested without special imperial order.[17] Juren households also had economic privileges in the local community, such as a guaranteed minimum level of employment and pay, as well as tax reductions and exemptions.[4][15]

Other privileges of the juren rank included the right of having different clothing, carriages, guards, servants, and funeral and grave ceremonies than commoners.[17] For example, degree-holders were entitled to wear a scholar's robe.[21]

Other usage

Military

During Wu Zetian's reign, a military examination system was introduced, which continued until the Qing dynasty.[3] The military examinations were modelled on the civil examination system,[3] held once every three years, with successful candidates being awarded the title of military juren, or wu juren (Chinese: 武舉人).[3] Military examinations involved various physical tests, such as ability in archery, equestrianism, and handling polearms.[3] Aside from the need for candidates to satisfactorily demonstrate their physical abilities, the military exams had written components that required candidates to master military or classic texts, such as Sun Tzu's The Art of War.[22] Only individuals with the wu juren title could participate in the metropolitan military exam, with successful candidates of this exam being awarded the military jinshi, or wu jinshi (Chinese: 武進士) title.[3]

Notable people

Notable people who achieved juren as their highest degree include:

- Shen Defu[23]

- Yang Shoujing

- Wei Yuan, scholar and secretariat

- Zuo Zongtang, general

- Liang Qichao, scholar and politician

- Wu Zhihui, anarchist writer and Republic of China official

- Huang Zunxian, Chinese official, scholar, and writer, active during the late Qing dynasty

- Zhu Xingyuan, politician and collaborator with Japan

References

- 1 2 Wang, Rui (2013). The Chinese Imperial Examination System: An Annotated Bibliography. Rowman & Littlefield.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bai, Ying; Jia, Ruixue (2016). "Elite Recruitment and Political Stability: The Impact of the Abolition of China's Civil Service Exam". Econometrica. 84 (2): 677–733. doi:10.3982/ecta13448. ISSN 0012-9682.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Theobald, Ulrich. "The Chinese Imperial Examination System (www.chinaknowledge.de)". www.chinaknowledge.de. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Zhang, Lawrence (2013). "Legacy of Success: Office Purchase and State-Elite Relations in Qing China". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 73 (2): 259–297. doi:10.1353/jas.2013.0020. ISSN 1944-6454. S2CID 154135928.

- 1 2 Theobald, Ulrich. "juren 舉人 (www.chinaknowledge.de)". www.chinaknowledge.de. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- ↑ Ch'ien, Mu (2019). "Merits and Demerits of Political Systems in Dynastic China". China Academic Library. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-58514-6. ISBN 978-3-662-58513-9. ISSN 2195-1853. S2CID 202313120.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Encyclopedia of Modern China. David Pong. Farmington Hills, MI. 2009. ISBN 978-0-684-31571-3. OCLC 432428521.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Cheung, Siu-Keung; Lee, Joseph Tse-Hei; Nedilsky, Lida V. (2009). Marginalization in China. doi:10.1057/9780230622418. ISBN 978-1-349-37844-9.

- 1 2 Zhang, Xiaojiang (2020), Zhang, Xiaojiang (ed.), "The History of China's Economic Structure Management", Mechanical Analysis of China's Macro Economic Structure: Fundamentals Behind Its Macro Investment Strategy Formulation, Singapore: Springer, pp. 1–16, doi:10.1007/978-981-15-3840-7_1, ISBN 978-981-15-3840-7, S2CID 216386846, retrieved 2021-05-15

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Lui, Adam Yuen-Chung (May 1974). "Syllabus of the Provincial Examination (hsiang-shih) under the Early Ch'ing (1644–1795)". Modern Asian Studies. 8 (3): 391–396. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00014694. ISSN 1469-8099. S2CID 144974513.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Civil Examination System in Late Imperial China, 1400–1900". Frontiers of History in China. 8 (1): 32–50. 5 March 2013. doi:10.3868/s020-002-013-0003-9. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "3. Circulation of Ming-Qing Elites". Civil Examinations and Meritocracy in Late Imperial China. Harvard University Press. 2013-11-01. pp. 95–125. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674726048.c5. ISBN 978-0-674-72604-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Giles, Herbert A. (2004). The Civilization of China. United States: 1st World Publishing, Incorporated. ISBN 9781595406514.

- 1 2 Chen, Ting; Kung, James Kai-sing; Ma, Chicheng (2020-10-16). "Long Live Keju! The Persistent Effects of China's Civil Examination System". The Economic Journal. 130 (631): 2030–2064. doi:10.1093/ej/ueaa043. ISSN 0013-0133.

- 1 2 Elman, Benjamin A. (February 1991). "Political, Social, and Cultural Reproduction via Civil Service Examinations in Late Imperial China". The Journal of Asian Studies. 50 (1): 7–28. doi:10.2307/2057472. ISSN 1752-0401. JSTOR 2057472. S2CID 154406547.

- 1 2 3 Weightman, Frances (2004). "Milestones on the Road to Maturity: Growing up with the Civil Service Examinations" (PDF). Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies. 4: 113–135.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ho, Ping-Ti (1962-03-02). The Ladder of Success in Imperial China. Columbia University Press. doi:10.7312/ho--93690. ISBN 978-0-231-89496-8.

- ↑ Herbert, Penelope Ann (1989). "Perceptions of Provincial Officialdom in Early T'ang China". Asia Major. 2 (1): 25–57. JSTOR 41645430 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Feng, Yuan (1995-01-01). "From the imperial examination to the national college entrance examination: The dynamics of political centralism in China's educational enterprise". Journal of Contemporary China. 4 (8): 28–56. doi:10.1080/10670569508724213. ISSN 1067-0564.

- ↑ Si, Hongchang (2018), Si, Hongchang (ed.), "Heritage of the Late Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China: Replacement of Old Education by New Education", A School in Ren Village: A Historical-Ethnographical Study of China's Educational Changes, Singapore: Springer, pp. 125–172, doi:10.1007/978-981-10-7225-3_5, ISBN 978-981-10-7225-3, retrieved 2021-05-15

- ↑ Bai, Ying (2019-11-01). "Farewell to Confucianism: The modernizing effect of dismantling China's imperial examination system". Journal of Development Economics. 141: 102–382. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2019.102382. ISSN 0304-3878. S2CID 14938561.

- ↑ Smith, Richard J. (1974). "Chinese military institutions in the mid-nineteenth century, 1850—1860". Journal of Asian History. 8 (2): 122–161. ISSN 0021-910X. JSTOR 41930145.

- ↑ Shen, Defu (1578). "Survey of the Legitimate and Illegitimate Dynasties in History". World Digital Library (in Chinese). Retrieved 7 June 2013.

.jpg.webp)