| Prince Pedro de Alcântara | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prince of Grão-Pará | |||||

| |||||

| Born | 15 October 1875 Petrópolis, Empire of Brazil | ||||

| Died | 29 January 1940 (aged 64) Petrópolis, Brazil | ||||

| Burial | Cathedral of São Pedro de Alcântara, Petrópolis | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | Princess Isabelle, Countess of Paris Prince Pedro Gastão Princess Maria Francisca, Duchess of Braganza Prince João Maria Princess Teresa | ||||

| |||||

| House | Orléans-Braganza | ||||

| Father | Prince Gaston, Count of Eu | ||||

| Mother | Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil | ||||

Dom Pedro de Alcântara of Orléans-Braganza, Prince of Grão Pará (15 October 1875 – 29 January 1940) was the first-born son of Dona Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil and Prince Gaston of Orléans, Count of Eu, and as such, was born second-in-line to the imperial throne of Brazil, during the reign of his grandfather, Emperor Dom Pedro II, until the empire's abolition. He went into exile in Europe with his mother when his grandfather was deposed in 1889, and grew up largely in France, at a family apartment in Boulogne-sur-Seine, and at his father's castle, the Château d'Eu in Normandy.[1]

Early life

Pedro was born on 15 October 1875 in the Imperial Palace of Petrópolis. He was the first son of Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil and her husband Prince Gaston, Count of Eu. As first son of the heiress-presumptive, he was Prince of Grão-Pará and second in line to the Brazilian throne.

Pedro was educated by preceptors, headed by the Baron of Ramiz, and lived in the Isabel Palace, in Rio de Janeiro with his younger brothers until The proclamation of the republic, on 15 November 1889, when he was fourteen years old.[2] One of his most poignant gestures on the occasion of the departure of the Brazilian imperial family to exile was when he suggested to his grandfather Emperor Pedro II "the idea of letting go a white dove on the high seas, which would take the last missive of the Brazilian imperial family." The family signed a message and then attached it to a dove, which was released at the highest point of Fernando de Noronha. However, the dove ended up falling to the sea without fulfilling its purpose.[3]

Exile

.jpg.webp)

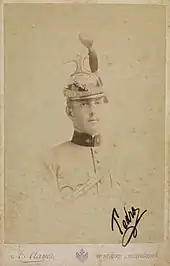

During the exile in 1890, Pedro moved along with their parents to the outskirts of Versailles.[4] He reached the age of majority in 1893, and without desire to assume the monarchist cause,[5] he left for Vienna, capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to study in the military school at Wiener Neustadt.[6] According to his own mother it was "clear that he must do something and a military career seems to us the only one he should follow".[6] His younger brothers Luís and Antônio followed him at the same military school. Pedro was formed as Lieutenant of the Austro-Hungarian Army at the 4th Regiment of Uhlans and was later Captain on the reserve.

In 1900 Pedro met Countess Elisabeth Dobržensky de Dobrženicz, a noblewoman of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, daughter of Johann-Wenzel, Count Dobrzensky von Dobrzenicz, who came from a former noble family of Bohemia,[7] and Elizabeth, Baroness Kottulin und Krzischkowitz and Countess Kottulinsky.[8] Count Dobrzensky von Dobrzenicz was elevated to the nobility title of count in 1906, at the request of Princess Isabel, until then his ancestors had been barons.[7] After eight years of courtship and engagement, they married in Versailles, France, on 14 November 1908. The couple had five children.

Restoration attempts

With the deposition of Pedro II of Brazil and the departure of the imperial family to the exile, rumors and even initiatives for the restoration appeared, occasionally. In 1893, the republic staggered with the second revolt of the navy and the federalist revolution in the south of the country. The leader of this last movement, Gaspar Silveira Martins, avowedly monarchist, was engaged in conspiracies to restore the parliamentary monarchy in Brazil. He had already insisted in vain that Pedro II should return to the country, after Marshal Deodoro had closed the National Congress. With the advance of the revolution, he proposed to Princess Isabel to allow the soldiers linked to the Army Revolt to take their eldest son, Pedro, Prince of Grão-Pará, to be acclaimed Dom Pedro III. He heard from the princess that "first of all she was a Catholic, and as such she could not leave the Brazilians with the education of her son, whose soul he had to save".[9] Outraged, Silveira Martins replied: "So, madam, his fate is the convent."

The House of Orléans-Braganza did not prepare itself to the risks of a bloody adventure in the south of Brazil. If, on the one hand, the Prince Imperial had given a revolution that had men and arms a soul, on the other hand, he spared himself the sad end of Custódio José de Melo, Gumercindo Saraiva, and so many others who measured forces against the republic.

Renunciation

In 1908 Dom Pedro wanted to marry Countess Elisabeth Dobržensky de Dobrženicz[2] (1875–1951) who, although a noblewoman of the Kingdom of Bohemia, did not belong to a royal or reigning dynasty. Although the constitution of the Brazilian Empire did not require a dynast to marry equally,[10] his mother ruled that the marriage would not be valid dynastically for the Brazilian succession,[10] and as a result he renounced his rights to the defunct throne of Brazil on 30 October 1908.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17] To solemnize this, Dom Pedro, aged thirty-three, signed the document translated here:

I Prince Pedro de Alcântara Luiz Filipe Maria Gastão Miguel Gabriel Rafael Gonzaga of Orléans and Braganza, having maturely reflected, have resolved to renounce the right that, by the Constitution of the Empire of Brazil, promulgated on 25 March 1824, accords to me the Crown of that nation. I declare, therefore, that by my free and spontaneous will I hereby renounce, in my own name, as well as for any and all of my descendants, to all and any rights that the aforesaid Constitution confers upon us to the Brazilian Crown and Throne, which shall pass to the lines which follow mine, conforming to the order of succession as established by article 117. Before God I promise, for myself and my descendants, to hold to the present declaration. Cannes 30 October 1908 signed: Pedro de Alcântara of Orléans-Braganza[18]

This renunciation was followed by a letter from Isabel to royalists in Brazil:

9 November 1908, [Castle of] Eu

Most Excellent Gentlemen Members of the Monarchist Directory,

With all my heart I thank you for the congratulations upon the marriages of my dear children Pedro and Luiz. Luis's took place in Cannes on the 4th with the brilliance that is desired for so solemn an act in the life of my successor to the Throne of Brazil. I was very pleased. Pedro's shall take place next on the 14th. Before the marriage of Luis he signed his resignation to the crown of Brazil, and here I send it to you, while keeping here an identical copy. I believe that this news must be published as soon as possible (you gentlemen shall do it in the way that you judge to be most satisfactory) in order to prevent the formation of parties that would be a great evil for our country. Pedro will continue to love his homeland, and will give all possible support to his brother. Thank God they are very united. Luis will engage actively in everything with respect to the monarchy and any good for our land. However, without giving up my rights I want that he be up to date on everything so that he may prepare himself for the position which with all my heart I desire that one day he will hold. You may write to him as many times as you may want to so that he shall be informed of everything. My strength is not the same as it once was, but my heart is still the same to love my homeland and all those who are so dedicated to us. I give you all my friendship and confidence,

a) Isabel, comtesse d'Eu

Nonetheless, a few years before his death Prince Pedro de Alcântara told a Brazilian newspaper:

- "My resignation was not valid for many reasons: besides, it was not a hereditary resignation."[19]

But years later he had rectified his position:

It is there that I intend to recover the rights of eventual succession to the throne of Brazil, with prejudice to d. Pedro Henrique, my nephew, denying my resignation in 1908. My resignation in 1908 is valid, although many monarchists ... understood that, politically and by the Brazilian laws in force in 1889, it must be ratified by the should the monarchy be restored. In fact, in my family there will never be dissensions or disputes over imperial power.

Death of the Princess Imperial

After the death of the Princess Imperial in 1921, the deceased Dom Luiz's son, Prince Pedro Henrique of Orléans-Braganza, assumed the position of claimant to the Brazilian throne and was recognized as such by many of Europe's dynasties.[19] After Dom Pedro de Alcântara's death in 1940 his eldest son, Prince Pedro Gastão of Orléans-Braganza, asserted a counter-claim as the proper successor (garnering the support of his brothers-in-law, the pretenders to the thrones of Orléanist France and Miguelist Portugal), and some Brazilian legal scholars subsequently argued that his father's renunciation would, indeed, have been constitutionally invalid under the monarchy.[19] Although Pedro de Alcântara's daughter, Princess Isabel, is said to have referred to Dom Pedro Gastão as "My brother, the Brazilian Emperor",[19] she acknowledged in her memoirs that their father nonetheless regarded his renunciation as binding, and treated it as effective.[20]

Return to Brazil

.png.webp)

Dom Pedro, after the decree exiling the imperial family was rescinded, came to Brazil to make hunting excursions in the Brazilian backlands. Accompanied by his secretary, he made between 1926 and 1927 one of the best-known trips of the time: the "auto-raid" from Bolivia to Rio de Janeiro, traveling four thousand kilometers by car on practically impassable roads. From this expedition there are reports published by Mario Baldi in Brazilian and European illustrated newspapers and magazines. Many photographs were made at the time; The images are part of the collection Mario Baldi, the secretary of culture of Teresópolis, city where the Austrian lived. Another expedition was made by the prince and his secretary, this time with the children of D. Pedro, in 1936.

On this occasion the expeditionaries visited indigenous villages of the Brazilian backwoods. The magazine A Noite Illustrada published several reports and photographs of Mario Baldi, who did the documentation of the adventure again. D. Pedro de Alcântara returned to Brazil in the decade of 1930, establishing itself in the Grão-Pará Palace, in Petrópolis. He became an obligatory figure in local celebrations and achievements, being greatly admired by the warm and friendly manner in which he always addressed his compatriots. In that same city the prince died, at 64 years of age, the victim of a respiratory illness, and was buried in the local cemetery with honors of head of state. In 1990, his remains were transferred along with his wife to the Imperial Mausoleum in the Cathedral of St. Peter of Alcantara in Petropolis, where they lie next to the tombs of their parents and grandparents in a simple vault.

Honors

Prince Pedro de Alcântara was a recipient of the following Brazilian dynastic orders:[21]

Grand Cross of the Order of Pedro I

Grand Cross of the Order of Pedro I.svg.png.webp) Grand Cross of the Order of the Rose

Grand Cross of the Order of the Rose Grand Cross of the Order of the Southern Cross

Grand Cross of the Order of the Southern Cross

He was a recipient of the following foreign honors:[21]

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (Japan)

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (Japan)

Issue

Pedro and Elisabeth married on 14 November 1908 in Versailles, France, and had 5 children :

- Princess Isabelle of Orléans-Braganza (1911–2003) married Henri, Count of Paris - grandparents of Prince Jean, Duke of Vendôme (born 1965), the current Orleanist pretender to the throne of France.

- Prince Pedro Gastão of Orléans-Braganza (1913–2007) married Princess Maria de la Esperanza of Bourbon-Two Sicilies - parents of Princess Maria da Gloria, Duchess of Segorbe, the last Crown Princess of Yugoslavia.

- Princess Maria Francisca of Orléans-Braganza (1914–1968) married Duarte Nuno, Duke of Braganza - parents of Duarte Pio, Duke of Braganza, the current pretender to the throne of Portugal.

- Prince João Maria of Orléans-Braganza (1916–2005) married Fatima Sherifa Chirine (1923-1990), widow of Prince Hassan Toussoun of Egypt.

- Princess Teresa of Orléans-Braganza (1919–2011) married Ernesto António Maria Martorell y Calderó (1921-1985).

After his death his son Prince Pedro Gastão assumed the headship of the Petrópolis branch of the Imperial House of Brazil.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Pedro de Alcântara, Prince of Grão-Pará |

|---|

References

- ↑ Montjouvent, Philippe de (1998). Le comte de Paris et sa Descendance (in French). Charenton: Éditions du Chaney. p. 50. ISBN 2-913211-00-3.

- 1 2 Villon, Victor. "Elisabeth Dobrzensky "Empress of Brazil"". Royalty Digest Quarterly.

- ↑ The last goodbye of the Imperial Family: The Prince of Grão-Pará try to send a dove carrying a message "miss of Brazil" to the mainland but the bird fell in the sea, for his wings were cut off, and drowned DEL PRIORE, Mary: O Príncipe Maldito, 2007. p.206

- ↑ Barman 2002, pp. 210–212.

- ↑ Barman 2002, p. 218.

- 1 2 Barman 2002, p. 220.

- 1 2 Johann-Wenzel Count Dobrzensky von Dobrzenicz Johann-Wenzel was head of the house of barons of Dobrzensky von Dobrzenicz since 4 November 1877; was elevated to the title of count on 21 February 1906.Cf.: MONJOUVENT, Philippe de: Le Comte de Paris, Duc de France et ses ancêtres. Charenton: Éditions du Chaney,2000.p.22

- ↑ Elisabeth, previous baroness, was elevated to the title of countess along with her husband MONJOUVENT, Philippe de: Le Comte de Paris, Duc de France et ses ancêtres. Charenton: Éditions du Chaney,2000.p.22

- ↑ CARVALHO, José Murilo de. D. Pedro II. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2007. Pg. 236

- 1 2 Sainty, Guy Stair. "House of Bourbon: Branch of Orléans-Braganza". Chivalric Orders. Archived from the original on 2008-10-25. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- ↑ BARMAN, Roderick J., Princesa Isabel do Brasil: gênero e poder no século XIX, UNESP, 2005

- ↑ VIANNA, Hélio. Vultos do Império. São Paulo: Companhia Editoria Nacional, 1968, p.224

- ↑ FREYRE, Gilberto. Ordem e Progresso. Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio, 1959, p.517 and 591

- ↑ LYRA, Heitor. História de Dom Pedro II - 1825-1891. São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional, 1940, vol.III, p.300

- ↑ Enciclopaedia Barsa, vol. IV, article "Braganza", p.210, 1992

- ↑ JANOTTI, Maria de Lourdes. Os Subversivos da República. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1986, p.255-7

- ↑ MALATIAN, Teresa Maria. A Ação Imperial Patrianovista Brasileira. São Paulo, 1978, p.153-9

- ↑ Montjouvent, Philippe de (1998). Le comte de Paris et sa Descendance (in French). Charenton: Éditions du Chaney. p. 97. ISBN 2-913211-00-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Bodstein, Astrid (2006). "The Imperial Family of Brazil". Royalty Digest Quarterly (3). Archived from the original on 2007-10-16. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- ↑ Tout m'est bonheur, tome 1 (Paris: R. Laffont, 1978), page 445 (French)

- 1 2 Smith de Vasconcelos, Rodolfo. Archivo Nobiliarchico Brasileiro. Lausanne: La Concorde, 1918, p.20

.svg.png.webp)