Prince-Bishopric of Brixen | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1027–1803 | |||||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||

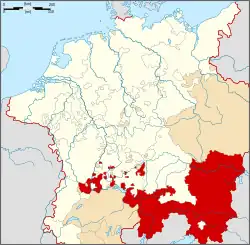

Ecclesiastical states of the Holy Roman Empire, 1648, with Brixen territories highlighted | |||||||||||

| Status | Prince-Bishopric | ||||||||||

| Capital | Brixen | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Southern Bavarian, Ladin | ||||||||||

| Government | Prince-Bishopric | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages Early modern period | ||||||||||

• Ingenuinus Bishop of Sabiona | 579 | ||||||||||

• Gained Reichsfreiheit | 1027 | ||||||||||

| 1179 | |||||||||||

• Joined Austrian Circle | 1512 | ||||||||||

| 1803 | |||||||||||

• To Austrian Empire | 1814 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Brixen Thaler | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Prince-Bishopric of Brixen (German: Hochstift Brixen, Fürstbistum Brixen, Bistum Brixen) was an ecclesiastical principality of the Holy Roman Empire in the present-day northern Italian province of South Tyrol. It should not be confused with the larger Catholic diocese, over which the prince-bishops exercised only the ecclesiastical authority of an ordinary bishop. The bishopric in the Eisack/Isarco valley was established in the 6th century and gradually received more secular powers. It gained imperial immediacy in 1027 and remained an Imperial Estate until 1803, when it was secularised to Tyrol. The diocese, however, existed until 1964, and is now part of the Diocese of Bolzano-Brixen.

History

The Diocese of Brixen is the continuation of that of Säben Abbey near Klausen, which, according to legend, was founded about 350 as Sabiona by Saint Cassian of Imola. As early as the 3rd century, Christianity had penetrated Sabiona, at that time a Roman custom station of considerable commercial importance. It may have been a retreat of the bishops of Augusta Vindelicorum, the later see of Augsburg, during the Migration Period.

Middle Ages

The first Bishop of Sabiona vouched for by history is Ingenuinus, mentioned about 580, who appears as suffragan of the Patriarchs of Aquileia. The tribes who pushed into the territory of the present Diocese of Brixen, during the great migratory movements, especially the Bavarians and Lombards, accepted Christianity at an early date; only the Slavs of the Puster Valley persisted in paganism until the 8th century. By the late 6th century the region became part of the Agilolfing stem duchy of Bavaria, which in 788 finally fell under Frankish overlordship. Urged by King Charlemagne, Pope Leo III assigned Säben as a suffragan diocese to the Archbishopric of Salzburg in 798. After King Louis the Child in 901 granted Säben the demesne of Prichsna, part of the estates held by his mother Ota, Bishop Rihpert (appointed 967) or Bishop Albuin I (967-1005) had the seat of the diocese transferred to Brixen.

Bishop Hartwig (1020–39) raised Brixen to the rank of a city, and surrounded it with fortifications. The diocese received many grants from the Holy Roman Emperors: thus from Conrad II in 1027 the suzerainty in the Norital, from Henry IV in 1091 the Puster Valley. In 1179 Frederick I Barbarossa conferred on the bishop the title and dignity of a prince of the Holy Roman Empire. This accounts for the fact that during the difficulties between the Papacy and the Empire, the Bishops of Brixen like the neighbouring Trent bishops generally took the part of the emperors. Particularly notorious is the case of Altwin, during whose episcopate (1049-1091) the ill-famed synod of 1080 was held in Brixen, at which thirty bishops, partisans of the emperor, declared Pope Gregory VII deposed, and set up as antipope the Bishop of Ravenna, with the name of Clement III.

The temporal power of the diocese soon suffered a marked diminution through the action of the bishops themselves, who bestowed large sections of their territory in fief on temporal lords: as for example, in the 11th century courtships in the Inntal and the Eisack valley (granted to the Counts of Tyrol, and in 1165 territory in the Inntal and the Puster Valley to the Counts of Andechs-Meran. The Counts of Tyrol, in particular, who had fallen heir in large part to the territories of the Duke of Merania, constantly grew in power. Bishop Bruno (1249-1288) had difficulty in asserting his authority over a section of his territory against the claims of Count Meinhard of Gorizia-Tyrol. Likewise Duke Frederick IV of Habsburg, ruler of Tyrol and Further Austria, called "of the Empty Pockets", compelled the Bishops of Brixen to acknowledge his authority. The dissensions between Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa (1450-1464), appointed by Pope Nicholas V as Bishop of Brixen, and the Austrian Archduke Sigismund of Habsburg were also unfortunate; the cardinal was made a prisoner, and although the pope placed the diocese under an interdict, Sigismund came out victor in the struggle.

Reformation and Austrian influence

The Reformation was proclaimed in the Diocese of Brixen during the episcopate of Christoph I von Schrofenstein (1509-1521) by German emissaries, like Strauss, Urban Regius, and others. In 1525, under Bishop Georg III of Austria (1525-1539), a peasants' uprising broke out in the vicinity of Brixen, and several monasteries and strongholds were destroyed. The promise of German king Ferdinand I of Habsburg, civil ruler of Tyrol, to redress the grievances of the peasants restored tranquility, and at a diet held at Innsbruck, the most important demands of the peasants were acceded to. Although in 1532 these promises were withdrawn, peace remained undisturbed.

Ferdinand I of Habsburg and his son Archduke Ferdinand II of Austria, in particular, as civil rulers took active measures against the adherents of the new teachings, chiefly the Anabaptists, who had been secretly propagating their sect; thus they preserved religious unity in the district of Tyrol and the Diocese of Brixen. At this time important services were rendered in safeguarding the Catholic Faith by the Jesuits, Capuchins, Franciscans, and Servites. Bishops of the period include: Cardinal Andrew of Austria (1591-1600), and Christoph IV von Spaur (1601-1613), who in 1607 founded a seminary for theological students; enlarged the cathedral school, and distinguished himself as a great benefactor of the poor and sick.

The 17th and 18th centuries many monasteries were founded, new missions for the cure of souls established, and the religious instruction of the people greatly promoted; in 1677 the University of Innsbruck was founded. The most prominent prince-bishops of this period were: Kaspar Ignaz, Count von Kunigl (1702–47), who founded many benefices for the care of souls, made diocesan visitations, kept a strict watch over the discipline and moral purity of his clergy, introduced missions under Jesuit Fathers, etc.; Leopold, Count von Spaur (1747-1778), who rebuilt the seminary, completed and consecrated the cathedral, and enjoyed the high esteem of Empress Maria Theresa; Joseph Philipp, Count von Spaur (1780-1791), a friend of learning, who, however, in his ecclesiastical policy, leaned towards Josephinism. The Government of Emperor Joseph II dealt roughly with church interests; about twenty monasteries of the diocese were suppressed, a general seminary was opened at Innsbruck, and pilgrimages and processions were forbidden. The Prince-Bishopric of Brixen as such was not affected.

Under Prince-Bishop Franz Karl, Count von Lodron (1791-1828), the temporal power of the prince-bishopric collapsed. In 1803 the principality was secularized, and annexed to Austria, and the cathedral chapter dissolved. During the brief rule of Bavaria after the 1805 Peace of Pressburg, the greatest despotism was exercised towards the Church; the restoration of Austrian supremacy in 1814 improved conditions for the former bishopric territory.

Bibliography

- Helmut Flachenecker, Hans Heiss, Hannes Obermair (eds.) (2000). Stadt und Hochstift, Brixen, Bruneck und Klausen bis zur Säkularisation 1803 – Città e Principato, Bressanone, Brunico e Chiusa fino alla secolarizzazione 1803 (= Veröffentlichungen des Südtiroler Landesarchivs 12), Verlagsanstalt Athesia, Bozen, ISBN 88-8266-084-2.

- Rudolf Leeb (2003). Geschichte des Christentums in Österreich. Von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. Uebereuter, Wien 2003, ISBN 3-8000-3914-1.

- Anselm Sparber (1957). Kirchengeschichte Tirols, im Grundriß dargestellt. Innsbruck-Wien-München (online).

- Wolfgang Wüst (2005). Sovranità principesco-vescovile nella prima età moderna. Un confronto tra le situazioni al di qua e al di là delle Alpi: Augusta, Bressanone, Costanza e Trento – Fürstliche Stiftsherrschaft in der Frühmoderne. Ein Vergleich süd- und nordalpiner Verhältnisse in Augsburg, Brixen, Eichstätt, Konstanz und Trient, in: Annali dell’Istituto storico italo-germanico in Trento – Jahrbuch des italienisch-deutschen historischen Instituts in Trient 30, Bologna, ISBN 88-15-10729-0, pp. 285–332.

See also

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)