Franklin D. Roosevelt | |

|---|---|

Official campaign portrait, 1944 | |

| 32nd President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1933 – April 12, 1945 | |

| Vice President |

|

| Preceded by | Herbert Hoover |

| Succeeded by | Harry S. Truman |

| 44th Governor of New York | |

| In office January 1, 1929 – December 31, 1932 | |

| Lieutenant | Herbert H. Lehman |

| Preceded by | Al Smith |

| Succeeded by | Herbert H. Lehman |

| Assistant Secretary of the Navy | |

| In office March 17, 1913 – August 26, 1920 | |

| President | Woodrow Wilson |

| Preceded by | Beekman Winthrop |

| Succeeded by | Gordon Woodbury |

| Member of the New York State Senate from the 26th district | |

| In office January 1, 1911 – March 17, 1913 | |

| Preceded by | John F. Schlosser |

| Succeeded by | James E. Towner |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Franklin Delano Roosevelt January 30, 1882 Hyde Park, New York, U.S. |

| Died | April 12, 1945 (aged 63) Warm Springs, Georgia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Springwood Estate |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 6, including Franklin Jr., Anna, Elliott, James II, and John II |

| Parents | |

| Relatives | |

| Education | |

| Signature | |

Franklin Delano Roosevelt[lower-alpha 1] (January 30, 1882 – April 12, 1945), commonly known by his initials FDR, was an American politician and statesman who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. He was a member of the Democratic Party and is the only U.S. president to have served more than two terms in office. His initial two were centered on combating the Great Depression, while his third and fourth saw him shift his focus to America's involvement in World War II.

A member of the prominent Roosevelt family, after attending university, Roosevelt began to practice law in New York City. He was elected a member of the New York State Senate from 1911 to 1913 and was then the assistant secretary of the Navy under President Woodrow Wilson during World War I. Roosevelt was James M. Cox's running mate on the Democratic Party's ticket in the 1920 U.S. presidential election, but Cox lost to Republican nominee Warren G. Harding. In 1921, Roosevelt contracted a paralytic illness that permanently paralyzed his legs. Partly through the encouragement of his wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, he returned to public office as governor of New York from 1929 to 1933, during which he promoted programs to combat the Great Depression besetting the U.S. In the 1932 presidential election, Roosevelt defeated Republican president Herbert Hoover in a landslide.

During his first 100 days as president, Roosevelt spearheaded unprecedented federal legislation and directed the federal government during most of the Great Depression, implementing the New Deal in response to the most significant economic crisis in American history. He also built the New Deal coalition, realigning American politics into the Fifth Party System and defining American liberalism throughout the middle third of the 20th century. He created numerous programs to provide relief to the unemployed and farmers while seeking economic recovery with the National Recovery Administration and other programs. He also instituted major regulatory reforms related to finance, communications, and labor, and presided over the end of Prohibition. In 1936, Roosevelt won a landslide reelection with the economy having improved from 1933, but the economy relapsed into a deep recession in 1937 and 1938. He was unable to expand the Supreme Court in 1937, the same year the conservative coalition was formed to block the implementation of further New Deal programs and reforms. Major surviving programs and legislation implemented under Roosevelt include the Securities and Exchange Commission, the National Labor Relations Act, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and Social Security. In 1940, he ran successfully for reelection, becoming the only American president to serve for more than two terms.

With World War II looming after 1938 in addition to the Japanese invasion of China and the aggression of Nazi Germany, Roosevelt gave strong diplomatic and financial support to China as well as the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union while the U.S. remained officially neutral. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, he obtained a declaration of war on Japan the next day and on Germany and Italy a few days later. He worked closely with other national leaders in leading the Allies against the Axis powers. Roosevelt supervised the mobilization of the American economy to support the war effort and implemented a Europe first strategy. He also initiated the development of the world's first atomic bomb and worked with the other Allied leaders to lay the groundwork for the United Nations and other post-war institutions, even coining the term "United Nations".[2] Roosevelt won reelection in 1944 but died in 1945 after his physical health seriously and steadily declined during the war years. Since then, several of his actions have come under substantial criticism, including his ordering of the internment of Japanese Americans in concentration camps. Nonetheless, historical rankings consistently place him as one of the greatest American presidents.

Early life and marriage

Childhood

Franklin Delano Roosevelt was born on January 30, 1882, in the Hudson Valley town of Hyde Park, New York, to businessman James Roosevelt I and his second wife, Sara Ann Delano. His parents, who were sixth cousins,[3] both came from wealthy, established New York families, the Roosevelts, the Aspinwalls and the Delanos, respectively. Roosevelt's paternal ancestor migrated to New Amsterdam in the 17th century, and the Roosevelts succeeded as merchants and landowners.[4] The Delano family patriarch, Philip Delano, traveled to the New World on the Fortune in 1621, and the Delanos thrived as merchants and shipbuilders in Massachusetts.[5] Franklin had a half-brother, James Roosevelt "Rosy" Roosevelt, from his father's previous marriage.[6]

Roosevelt's father, James, graduated from Harvard Law School in 1851 but chose not to practice law after receiving an inheritance from his grandfather.[6] James Roosevelt, a prominent Bourbon Democrat, once took Franklin to meet President Grover Cleveland, who said to him: "My little man, I am making a strange wish for you. It is that you may never be President of the United States."[7] Franklin's mother, the dominant influence in his early years, once declared, "My son Franklin is a Delano, not a Roosevelt at all."[3][8] James, who was 54 when Franklin was born, was considered by some as a remote father, though biographer James MacGregor Burns indicates James interacted with his son more than was typical at the time.[9]

Education and early career

As a child, Roosevelt learned to ride, shoot, and sail; he also learned to play polo, tennis, and golf.[10][11] Frequent trips to Europe—beginning at age two and from age seven to fifteen—helped Roosevelt become conversant in German and French. Except for attending public school in Germany at age nine,[12] Roosevelt was home-schooled by tutors until age 14. He then attended Groton School, an Episcopal boarding school in Groton, Massachusetts.[13] He was not among the more popular Groton students, who were better athletes and had rebellious streaks.[14] Its headmaster, Endicott Peabody, preached the duty of Christians to help the less fortunate and urged his students to enter public service. Peabody remained a strong influence throughout Roosevelt's life, officiating at his wedding and visiting him as president.[15][16]

Like most of his Groton classmates, Roosevelt went to Harvard College.[14] He was a member of the Alpha Delta Phi fraternity[17] and the Fly Club,[18] and served as a school cheerleader.[19] Roosevelt was relatively undistinguished as a student or athlete, but he became editor-in-chief of The Harvard Crimson daily newspaper, a position that required ambition, energy, and the ability to manage others.[20] He later said, "I took economics courses in college for four years, and everything I was taught was wrong."[21]

Roosevelt's father died in 1900, causing great distress for him.[22] The following year, Roosevelt's fifth cousin Theodore Roosevelt became President of the United States. Theodore's vigorous leadership style and reforming zeal made him Franklin's role model and hero.[23] He graduated from Harvard in three years in 1903 with an A.B. in history.[24] He remained there for a fourth year, taking graduate courses and becoming an editor of the Harvard Crimson.[25]

Roosevelt entered Columbia Law School in 1904 but dropped out in 1907 after passing the New York Bar Examination.[26][lower-alpha 2] In 1908, he took a job with the prestigious law firm of Carter Ledyard & Milburn, working in the firm's admiralty law division.[28]

Marriage, family, and marital affairs

During his second year of college, Roosevelt met and proposed to Boston heiress Alice Sohier, who turned him down.[14] Franklin then began courting his child-acquaintance and fifth cousin once removed, Eleanor Roosevelt, a niece of Theodore Roosevelt.[29] In 1903, Franklin proposed to Eleanor. Following resistance from Roosevelt's mother, Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt were married on March 17, 1905.[14][30] Eleanor's father, Elliott, was deceased; her uncle Theodore, who was then the president of the United States, gave away the bride.[31] The young couple moved into Springwood. Franklin and Sara Roosevelt also provided a townhouse for the newlyweds in New York City, and Sara had a house built for herself alongside that townhouse. Eleanor never felt at home in the houses at Hyde Park or New York; however, she loved the family's vacation home on Campobello Island, which Sara also gave the couple.[32] Burns indicates that young Franklin Roosevelt was self-assured and at ease in the upper class. On the other hands, Eleanor was then shy and disliked social life. Initially, Eleanor stayed home to raise their children.[33] As his father had done, Franklin left the raising of the children to his wife, and Eleanor delegated the task to caregivers. She later said that she knew "absolutely nothing about handling or feeding a baby."[34] Although Eleanor thought sex was "an ordeal to be endured",[35] she and Franklin had six children. Anna, James, and Elliott were born in 1906, 1907, and 1910, respectively. The couple's second son, Franklin, died in infancy in 1909. Another son, also named Franklin, was born in 1914, and the youngest child, John, was born in 1916.[36]

Roosevelt had several extramarital affairs. He commenced an affair with Eleanor's social secretary, Lucy Mercer, soon after she was hired in 1914. That affair was discovered by Eleanor in 1918.[37] Franklin contemplated divorcing Eleanor, but Sara objected, and Mercer would not marry a divorced man with five children.[38] Franklin and Eleanor remained married, and Franklin promised never to see Mercer again. Eleanor never forgave him for the affair, and their marriage shifted to become a political partnership.[39] Eleanor soon established a separate home in Hyde Park at Val-Kill and devoted herself to social and political causes independent of her husband. The emotional break in their marriage was so severe that when Franklin asked Eleanor in 1942—in light of his failing health—to come back home and live with him again, she refused.[40] Roosevelt was not always aware of Eleanor's visits to the White House. For some time, Eleanor could not easily reach Roosevelt on the telephone without his secretary's help; Franklin, in turn, did not visit Eleanor's New York City apartment until late 1944.[41]

Franklin broke his promise to Eleanor regarding Lucy Mercer. He and Mercer maintained a formal correspondence and began seeing each other again in 1941 or earlier.[42][43] Roosevelt's son Elliott claimed that his father had a 20-year affair with his private secretary, Marguerite "Missy" LeHand.[44] Another son, James, stated that "there is a real possibility that a romantic relationship existed" between his father and Crown Princess Märtha of Norway, who resided in the White House during part of World War II. Aides began to refer to her at the time as "the president's girlfriend",[45] and gossip linking the two romantically appeared in the newspapers.[46]

Early political career (1910–1920)

New York state senator (1910–1913)

Roosevelt cared little for the practice of law and told friends he planned to enter politics.[47] Despite his admiration for cousin Theodore, Franklin shared his father's bond with the Democratic Party, and in preparation for the 1910 elections, the party recruited Roosevelt to run for a seat in the New York State Assembly.[48] Roosevelt was a compelling recruit for the party. He had the personality and energy for campaigning, and he had the money to pay for his own campaign.[49] But Roosevelt's campaign for the state assembly ended after the Democratic incumbent, Lewis Stuyvesant Chanler, chose to seek re-election. Rather than putting his political hopes on hold, Roosevelt ran for a seat in the state senate.[50] The senate district, located in Dutchess, Columbia, and Putnam, was strongly Republican.[51] Roosevelt feared that opposition from Theodore could end his campaign, but Theodore encouraged his candidacy despite their party differences.[48] Acting as his own campaign manager, Roosevelt traveled throughout the senate district via automobile at a time when few could afford a car.[52] Due to his aggressive campaign,[53] his name recognition in the Hudson Valley, and the Democratic landslide in the 1910 United States elections, Roosevelt won a surprising victory.[54]

Despite short legislative sessions, Roosevelt treated his new position as a full-time career.[55] Taking his seat on January 1, 1911, Roosevelt soon became the leader of a group of "Insurgents" in opposition to the Tammany Hall machine that dominated the state Democratic Party. In the 1911 U.S. Senate election, which was determined in a joint session of the New York state legislature,[lower-alpha 3] Roosevelt and nineteen other Democrats caused a prolonged deadlock by opposing a series of Tammany-backed candidates. Tammany threw its backing behind James A. O'Gorman, a highly regarded judge whom Roosevelt found acceptable, and O'Gorman won the election in late March.[56] Roosevelt in the process became a popular figure among New York Democrats.[54] News articles and cartoons depicted "the second coming of a Roosevelt", sending "cold shivers down the spine of Tammany".[57]

Roosevelt opposed Tammany Hall by supporting New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson's successful bid for the 1912 Democratic nomination.[58] The election became a three-way contest when Theodore Roosevelt left the Republican Party to launch a third-party campaign against Wilson and sitting Republican President William Howard Taft. Franklin's decision to back Wilson over his cousin in the general election alienated some of his family, except Theodore.[59] Roosevelt overcame a bout of typhoid fever, and with help from journalist Louis McHenry Howe, he was re-elected in the 1912 elections. After the election, he served as chairman of the Agriculture Committee, and his success with farm and labor bills was a precursor to his New Deal policies years later.[60] He had then become more consistently progressive, in support of labor and social welfare programs.[61]

Assistant Secretary of the Navy (1913–1919)

Roosevelt's support of Wilson led to his appointment in March 1913 as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, the second-ranking official in the Navy Department after Secretary Josephus Daniels who paid it little attention.[62] Roosevelt had an affection for the Navy, was well-read on the subject, and was a most ardent supporter of a large, efficient force.[63][64] With Wilson's support, Daniels and Roosevelt instituted a merit-based promotion system and made other reforms to extend civilian control over the autonomous departments of the Navy.[65] Roosevelt oversaw the Navy's civilian employees and earned the respect of union leaders for his fairness in resolving disputes.[66] No strikes occurred during his seven-plus years in the office,[67] as he gained valuable experience in labor issues, wartime management, naval issues, and logistics.[68]

In 1914, Roosevelt ran for the seat of retiring Republican Senator Elihu Root of New York. Though he had the backing of Treasury Secretary William Gibbs McAdoo and Governor Martin H. Glynn, he faced a formidable opponent in Tammany-Hall's James W. Gerard.[69] He also was without Wilson's support, as the president needed Tammany's forces for his legislation and 1916 re-election.[70] Roosevelt was soundly defeated in the Democratic primary by Gerard, who in turn lost the general election to Republican James Wolcott Wadsworth Jr. He learned that federal patronage alone, without White House support, could not defeat a strong local organization.[71] After the election, he and Tammany Hall boss Charles Francis Murphy sought accommodation and became allies.[72]

Roosevelt refocused on the Navy Department, as World War I broke out in Europe in August 1914.[73] Though he remained publicly supportive of Wilson, Roosevelt sympathized with the Preparedness Movement, whose leaders strongly favored the Allied Powers and called for a military build-up.[74] The Wilson administration initiated an expansion of the Navy after the sinking of the RMS Lusitania by a German submarine, and Roosevelt helped establish the United States Navy Reserve and the Council of National Defense.[75] In April 1917, after Germany declared it would engage in unrestricted submarine warfare and attacked several U.S. ships, Congress approved Wilson's call for a declaration of war on Germany.[76]

Roosevelt requested that he be allowed to serve as a naval officer, but Wilson insisted that he continue to serve as Assistant Secretary. For the next year, Roosevelt remained in Washington to coordinate the deployment of naval vessels and personnel, as the Navy expanded fourfold.[77][78] In the summer of 1918, Roosevelt traveled to Europe to inspect naval installations and meet with French and British officials. In September, he returned to the United States on board the USS Leviathan. On the 11-day voyage, the pandemic influenza virus struck and killed many on board. Roosevelt became very ill with influenza and complicating pneumonia but recovered by the time the ship landed in New York.[79][80] After Germany signed an armistice in November 1918, Daniels and Roosevelt supervised the demobilization of the Navy.[81] Against the advice of older officers such as Admiral William Benson—who claimed he could not "conceive of any use the fleet will ever have for aviation"—Roosevelt personally ordered the preservation of the Navy's Aviation Division.[82] With the Wilson administration near an end, Roosevelt planned his next run for office. He approached Herbert Hoover about running for the 1920 Democratic presidential nomination, with Roosevelt as his running mate.[83]

Campaign for vice president (1920)

Roosevelt's plan for Hoover to run for the nomination fell through after Hoover publicly declared himself to be a Republican, but Roosevelt decided to seek the 1920 vice presidential nomination. After Governor James M. Cox of Ohio won the party's presidential nomination at the 1920 Democratic National Convention, he chose Roosevelt as his running mate, and the convention nominated him by acclamation.[84] Although his nomination surprised most people, he balanced the ticket as a moderate, a Wilsonian, and a prohibitionist with a famous name.[85][86] Roosevelt, then 38, resigned as Assistant Secretary after the Democratic convention and campaigned across the nation for the party ticket.[87]

During the campaign, Cox and Roosevelt defended the Wilson administration and the League of Nations, both of which were unpopular in 1920.[88] Roosevelt personally supported U.S. membership in the League of Nations, but, unlike Wilson, he favored compromising with Senator Henry Cabot Lodge and other "Reservationists".[89] The Cox–Roosevelt ticket was defeated by Republicans Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge in the presidential election by a wide margin, and the Republican ticket carried every state outside of the South.[90] Roosevelt accepted the loss without issue and later reflected that the relationships and goodwill that he built in the 1920 campaign proved to be a major asset in his 1932 campaign. The 1920 election also saw the first public participation of Eleanor Roosevelt who, with the support of Louis Howe, established herself as a valuable political player.[91] After the election, Roosevelt returned to New York City, where he practiced law and served as a vice president of the Fidelity and Deposit Company.[92]

Paralytic illness and political comeback (1921–1928)

Roosevelt sought to build support for a political comeback in the 1922 elections, but his career was derailed by an illness which began less than three weeks after the U.S. Senate Committee on Naval Affairs issued its final report the Newport Sex Scandal.[92] While the Roosevelts were vacationing at Campobello Island in August 1921, he fell ill. His main symptoms were fever; symmetric, ascending paralysis; facial paralysis; bowel and bladder dysfunction; numbness and hyperesthesia; and a descending pattern of recovery. Roosevelt was left permanently paralyzed from the waist down and was diagnosed with polio. Historians have noted a 2003 study strongly favoring a diagnosis of Guillain–Barré syndrome,[93] but have continued to describe his paralysis according to the initial diagnosis.[94][95][96][97]

Though his mother favored his retirement from public life, Roosevelt, his wife, and Roosevelt's close friend and adviser, Louis Howe, were all determined that he continue his political career.[98] He convinced many people that he was improving, which he believed to be essential prior to running for public office again.[99] He laboriously taught himself to walk short distances while wearing iron braces on his hips and legs, by swiveling his torso while supporting himself with a cane.[100] He was careful never to be seen using his wheelchair in public, and great care was taken to prevent any portrayal in the press that would highlight his disability.[101] However, his disability was well known before and during his presidency and became a major part of his image. He usually appeared in public standing upright, supported on one side by an aide or one of his sons.[102]

Beginning in 1925, Roosevelt spent most of his time in the Southern United States, at first on his houseboat, the Larooco.[103] Intrigued by the potential benefits of hydrotherapy, he established a rehabilitation center at Warm Springs, Georgia, in 1926. To create the rehabilitation center, he assembled a staff of physical therapists and used most of his inheritance to purchase the Merriweather Inn. In 1938, he founded the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, leading to the development of polio vaccines.[104]

Roosevelt maintained contacts with the Democratic Party during the 1920s, and he remained active in New York politics while also establishing contacts in the South, particularly in Georgia.[105] He issued an open letter endorsing Al Smith's successful campaign in New York's 1922 gubernatorial election, which both aided Smith and showed Roosevelt's continuing relevance as a political figure.[106] Roosevelt and Smith came from different backgrounds and never fully trusted one another, but Roosevelt supported Smith's progressive policies, while Smith was happy to have the backing of the prominent and well-respected Roosevelt.[107]

Roosevelt gave presidential nominating speeches for Smith at the 1924 and 1928 Democratic National Conventions; the speech at the 1924 convention marked a return to public life following his illness and convalescence.[108] That year, the Democrats were badly divided between an urban wing, led by Smith, and a conservative, rural wing, led by William Gibbs McAdoo. On the 101st ballot, the nomination went to John W. Davis, a compromise candidate who suffered a landslide defeat in the 1924 presidential election. Like many others throughout the United States, Roosevelt did not abstain from alcohol during the Prohibition era, but publicly he sought to find a compromise on Prohibition acceptable to both wings of the party.[109]

In 1925, Smith appointed Roosevelt to the Taconic State Park Commission, and his fellow commissioners chose him as chairman.[110] In this role, he came into conflict with Robert Moses, a Smith protégé,[110] who was the primary force behind the Long Island State Park Commission and the New York State Council of Parks.[110] Roosevelt accused Moses of using the name recognition of prominent individuals including Roosevelt to win political support for state parks, but then diverting funds to the ones Moses favored on Long Island, while Moses worked to block the appointment of Howe to a salaried position as the Taconic commission's secretary.[110] Roosevelt served on the commission until the end of 1928,[111] and his contentious relationship with Moses continued as their careers progressed.[112]

Peace was the catchword of the 1920s, and in 1923 Edward Bok established the $100,000 American Peace Award for the best plan to bring peace to the world. Roosevelt had leisure time and interest, and he drafted a plan for the contest. He never submitted it because his wife Eleanor Roosevelt was selected as a judge for the prize. His plan called for a new world organization that would replace the League of Nations.[113] Although Roosevelt had been the vice-presidential candidate on the Democratic ticket of 1920 that supported the League of Nations, by 1924 he was ready to scrap it. His draft of a "Society of Nations" accepted the reservations proposed by Henry Cabot Lodge in the 1919 Senate debate. The new Society would not become involved in the Western Hemisphere, where the Monroe doctrine held sway. It would not have any control over military forces. Although Roosevelt's plan was never made public, he thought about the problem a great deal and incorporated some of his 1924 ideas into the design for the United Nations in 1944–1945.[114]

Governor of New York (1929–1932)

Smith, the Democratic presidential nominee in the 1928 election, asked Roosevelt to run for governor of New York in the 1928 state election.[115] Roosevelt initially resisted, as he was reluctant to leave Warm Springs and feared a Republican landslide in 1928.[116] Party leaders eventually convinced him only he could defeat the Republican gubernatorial nominee, New York Attorney General Albert Ottinger.[117] He won the party's gubernatorial nomination by acclamation and again turned to Howe to lead his campaign. Roosevelt was also joined on the campaign trail by associates Samuel Rosenman, Frances Perkins, and James Farley.[118] While Smith lost the presidency in a landslide, and was defeated in his home state, Roosevelt was elected governor by a one-percent margin,[119] and became a contender in the next presidential election.[120]

Roosevelt proposed the construction of hydroelectric power plants and addressed the ongoing farm crisis of the 1920s.[121] Relations between Roosevelt and Smith suffered after he chose not to retain key Smith appointees like Moses.[122] He and his wife Eleanor established an understanding for the rest of his career; she would dutifully serve as the governor's wife but would also be free to pursue her own agenda and interests.[123] He also began holding "fireside chats", in which he directly addressed his constituents via radio, often pressuring the New York State Legislature to advance his agenda.[124]

In October 1929, the Wall Street Crash occurred, and with it came the Great Depression in the United States.[125] Roosevelt saw the seriousness of the situation and established a state employment commission. He also became the first governor to publicly endorse the idea of unemployment insurance.[126]

When Roosevelt began his run for a second term in May 1930, he reiterated his doctrine from the campaign two years before: "that progressive government by its very terms must be a living and growing thing, that the battle for it is never-ending and that if we let up for one single moment or one single year, not merely do we stand still but we fall back in the march of civilization."[127] He ran on a platform that called for aid to farmers, full employment, unemployment insurance, and old-age pensions.[128] He was elected to a second term by a 14% margin.[129]

Roosevelt proposed an economic relief package and the establishment of the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration to distribute those funds. Led first by Jesse I. Straus and then by Harry Hopkins, the agency assisted well over one-third of New York's population between 1932 and 1938.[130] Roosevelt also began an investigation into corruption in New York City among the judiciary, the police force, and organized crime, prompting the creation of the Seabury Commission. The Seabury investigations exposed an extortion ring, led many public officials to be removed from office, and made the decline of Tammany Hall inevitable.[131]

Roosevelt supported reforestation with the Hewitt Amendment in 1931, which gave birth to New York's State Forest system.[132]

1932 presidential election

As the 1932 presidential election approached, Roosevelt turned his attention to national politics, established a campaign team led by Howe and Farley, and a "brain trust" of policy advisers, primarily composed of Columbia University and Harvard University professors.[133] There were some who were not so sanguine about his chances, such as Walter Lippmann, the dean of political commentators, who observed of Roosevelt: "He is a pleasant man who, without any important qualifications for the office, would very much like to be president."[134]

However, Roosevelt's efforts as governor to address the effects of the depression in his own state established him as the front-runner for the 1932 Democratic presidential nomination.[134] Roosevelt rallied the progressive supporters of the Wilson administration while also appealing to many conservatives, establishing himself as the leading candidate in the South and West. The chief opposition to Roosevelt's candidacy came from Northeastern conservatives, Speaker of the House John Nance Garner of Texas and Al Smith, the 1928 Democratic presidential nominee.[134]

Roosevelt entered the convention with a delegate lead due to his success in the 1932 Democratic primaries, but most delegates entered the convention unbound to any particular candidate. On the first presidential ballot of the convention, Roosevelt received the votes of more than half but less than two-thirds of the delegates, with Smith finishing in a distant second place. Roosevelt then promised the vice-presidential nomination to Garner, who controlled the votes of Texas and California; Garner threw his support behind Roosevelt after the third ballot, and Roosevelt clinched the nomination on the fourth ballot.[134] Roosevelt flew in from New York to Chicago after learning that he had won the nomination, becoming the first major-party presidential nominee to accept the nomination in person.[135] His appearance was essential, to show himself as vigorous, despite the ravaging disease that disabled him physically.[134]

In his acceptance speech, Roosevelt declared, "I pledge you, I pledge myself to a new deal for the American people... This is more than a political campaign. It is a call to arms."[136] Roosevelt promised securities regulation, tariff reduction, farm relief, government-funded public works, and other government actions to address the Great Depression.[137] Reflecting changing public opinion, the Democratic platform included a call for the repeal of Prohibition; Roosevelt himself had not taken a public stand on the issue prior to the convention but promised to uphold the party platform.[138] Otherwise, Roosevelt's primary campaign strategy was one of caution, intent upon avoiding mistakes that would distract from Hoover's failings on the economy. His statements attacked the incumbent and included no other specific policies or programs.[134]

After the convention, Roosevelt won endorsements from several progressive Republicans, including George W. Norris, Hiram Johnson, and Robert La Follette Jr.[139] He also reconciled with the party's conservative wing, and even Al Smith was persuaded to support the Democratic ticket.[140] Hoover's handling of the Bonus Army further damaged the incumbent's popularity, as newspapers across the country criticized the use of force to disperse assembled veterans.[141]

Roosevelt won 57% of the popular vote and carried all but six states. Historians and political scientists consider the 1932–36 elections to be a political realignment. Roosevelt's victory was enabled by the creation of the New Deal coalition, small farmers, the Southern whites, Catholics, big city political machines, labor unions, northern black Americans (southern ones were still disfranchised), Jews, intellectuals, and political liberals.[142] The creation of the New Deal coalition transformed American politics and started what political scientists call the "New Deal Party System" or the Fifth Party System.[143] Between the Civil War and 1929, Democrats had rarely controlled both houses of Congress and had won just four of seventeen presidential elections; from 1932 to 1979, Democrats won eight of twelve presidential elections and generally controlled both houses of Congress.[144]

Transition and assassination attempt

Roosevelt was elected in November 1932 but like his predecessors did not take office until the following March.[lower-alpha 4] After the election, President Hoover sought to convince Roosevelt to renounce much of his campaign platform and to endorse the Hoover administration's policies.[145] Roosevelt refused Hoover's request to develop a joint program to stop the economic decline, claiming that it would tie his hands and that Hoover had the power to act.[146]

During the transition, Roosevelt chose Howe as his chief of staff, and Farley as Postmaster General. Frances Perkins, as Secretary of Labor, became the first woman appointed to a cabinet position.[134] William H. Woodin, a Republican industrialist close to Roosevelt, was the choice for Secretary of the Treasury, while Roosevelt chose Senator Cordell Hull of Tennessee as Secretary of State. Harold L. Ickes and Henry A. Wallace, two progressive Republicans, were selected for the roles of Secretary of the Interior and Secretary of Agriculture, respectively.[147]

In February 1933, Roosevelt escaped an assassination attempt by Giuseppe Zangara, who expressed a "hate for all rulers." As he was attempting to shoot Roosevelt, Zangara was struck by a woman with her purse; he instead mortally wounded Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak, who was sitting alongside Roosevelt.[148][149]

Presidency (1933–1945)

As president, Roosevelt appointed powerful men to top positions but made all the major decisions, regardless of delays, inefficiency, or resentment. Analyzing the president's administrative style, Burns concludes:

The president stayed in charge of his administration...by drawing fully on his formal and informal powers as Chief Executive; by raising goals, creating momentum, inspiring a personal loyalty, getting the best out of people...by deliberately fostering among his aides a sense of competition and a clash of wills that led to disarray, heartbreak, and anger but also set off pulses of executive energy and sparks of creativity...by handing out one job to several men and several jobs to one man, thus strengthening his own position as a court of appeals, as a depository of information, and as a tool of co-ordination; by ignoring or bypassing collective decision-making agencies, such as the Cabinet...and always by persuading, flattering, juggling, improvising, reshuffling, harmonizing, conciliating, manipulating.[150]

First and second terms (1933–1941)

When Roosevelt was inaugurated on March 4, 1933, the U.S. was at the nadir of the worst depression in its history. A quarter of the workforce was unemployed, and farmers were in deep trouble as prices had fallen by 60%. Industrial production had fallen by more than half since 1929. Two million people were homeless. By the evening of March 4, 32 of the 48 states—as well as the District of Columbia—had closed their banks.[151]

Historians categorized Roosevelt's program as "relief, recovery, and reform." Relief was urgently needed by tens of millions of unemployed. Recovery meant boosting the economy back to normal, and reform was required of the financial and banking systems. Through Roosevelt's series of 30 "fireside chats", he presented his proposals directly to the American public as a series of radio addresses.[152] Energized by his own victory over paralytic illness, he used persistent optimism and activism to renew the national spirit.[153]

First New Deal (1933–1934)

On his second day in office, Roosevelt declared a four-day national "bank holiday", to end the run by depositors seeking to withdraw funds.[154] He called for a special session of Congress on March 9, when Congress passed, almost sight unseen, the Emergency Banking Act.[154] The act, first developed by the Hoover administration and Wall Street bankers, gave the president the power to determine the opening and closing of banks and authorized the Federal Reserve Banks to issue banknotes.[155] The "first 100 Days" of the 73rd United States Congress saw an unprecedented amount of legislation and set a benchmark against which future presidents have been compared.[156][157] When the banks reopened on Monday, March 15, stock prices rose by 15 percent and in the following weeks over $1 billion was returned to bank vaults, ending the bank panic.[154] On March 22, Roosevelt signed the Cullen–Harrison Act, which brought Prohibition to a close.[158]

Roosevelt saw the establishment of a number of agencies and measures designed to provide relief for the unemployed and others. The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), under the leadership of Harry Hopkins, distributed relief to state governments.[159] The Public Works Administration (PWA), under Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, oversaw the construction of large-scale public works such as dams, bridges, and schools.[159] The most popular of all New Deal agencies—and Roosevelt's favorite—was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which hired 250,000 unemployed men to work in rural projects. Roosevelt also expanded Hoover's Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which financed railroads and industry. Congress gave the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) broad regulatory powers and provided mortgage relief to millions of farmers and homeowners. Roosevelt also set up the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) to increase commodity prices, by paying farmers to leave land uncultivated and cut herds.[160] In many instances, crops were plowed under and livestock killed, while many Americans died of hunger and were ill-clothed; critics labeled such policies "utterly idiotic."[154] On the positive side, nothing did more to rescue the farm family from isolation than the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), which brought electricity for the first time to millions of rural homes and with it such conveniences as radios and washing machines."[154]

Reform of the economy was the goal of the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) of 1933. It sought to end cutthroat competition by forcing industries to establish rules such as minimum prices, agreements not to compete, and production restrictions. Industry leaders negotiated the rules with NIRA officials, who suspended antitrust laws in return for better wages. The Supreme Court in May 1935 declared NIRA unconstitutional by a unanimous decision, to Roosevelt's chagrin.[161] He reformed financial regulations with the Glass–Steagall Act, creating the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to underwrite savings deposits. The act also limited affiliations between commercial banks and securities firms.[162] In 1934, the Securities and Exchange Commission was created to regulate the trading of securities, while the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) was established to regulate telecommunications.[163]

Recovery was sought through federal spending, as the NIRA included $3.3 billion (equivalent to $74.6 billion in 2022) of spending through the Public Works Administration.[164] Roosevelt worked with Senator Norris to create the largest government-owned industrial enterprise in American history—the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA)—which built dams and power stations, controlled floods, and modernized agriculture and home conditions in the poverty-stricken Tennessee Valley. However, natives criticized the TVA for displacing thousands of people for these projects.[154] The Soil Conservation Service trained farmers in the proper methods of cultivation, and with the TVA, Roosevelt became the father of soil conservation.[154] Executive Order 6102 declared that all privately held gold of American citizens was to be sold to the U.S. Treasury and the price raised from $20 to $35 per ounce. The goal was to counter the deflation which was paralyzing the economy.[165]

Roosevelt tried to keep his campaign promise by cutting the federal budget. This included a reduction in military spending from $752 million in 1932 to $531 million in 1934 and a 40% cut in spending on veterans benefits. 500,000 veterans and widows were removed from the pension rolls, and benefits were reduced for the remainder. Federal salaries were cut and spending on research and education was reduced. The veterans were well organized and strongly protested, so most benefits were restored or increased by 1934.[166] Veterans groups such as the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars won their campaign to transform their benefits from payments due in 1945 to immediate cash when Congress overrode the President's veto and passed the Bonus Act in January 1936.[167] It pumped sums equal to 2% of the GDP into the consumer economy and had a major stimulus effect.[168]

Second New Deal (1935–1936)

Roosevelt expected that his party would lose seats in the 1934 Congressional elections, as the president's party had done in most previous midterm elections. Unexpectedly the Democrats picked up seats in both houses of Congress. Empowered by the public's vote of confidence, the first item on Roosevelt's agenda in the 74th Congress was the creation of a social insurance program.[169] The Social Security Act established Social Security and promised economic security for the elderly, the poor, and the sick. Roosevelt insisted that it should be funded by payroll taxes rather than from the general fund, saying, "We put those payroll contributions there so as to give the contributors a legal, moral, and political right to collect their pensions and unemployment benefits. With those taxes in there, no damn politician can ever scrap my social security program."[170] Compared with the social security systems in western European countries, the Social Security Act of 1935 was rather conservative. But for the first time, the federal government took responsibility for the economic security of the aged, the temporarily unemployed, dependent children, and disabled people.[171] Against Roosevelt's original intention for universal coverage, the act excluded farmers, domestic workers, and other groups, which made up about forty percent of the labor force.[172]

Roosevelt consolidated the various relief organizations, though some, like the PWA, continued to exist. After winning Congressional authorization for further funding of relief efforts, he established the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Under the leadership of Harry Hopkins, the WPA employed over three million people in its first year of operations. It undertook numerous massive construction projects in cooperation with local governments. It also set up the National Youth Administration and arts organizations.[173]

The National Labor Relations Act guaranteed workers the right to collective bargaining through unions of their own choice. The act also established the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to facilitate wage agreements and suppress repeated labor disturbances. The act did not compel employers to reach an agreement with their employees, but it opened possibilities for American labor.[174] The result was a tremendous growth of membership in the labor unions, especially in the mass-production sector.[175] When the Flint sit-down strike threatened the production of General Motors, Roosevelt broke with the precedent set by many former presidents and refused to intervene; the strike ultimately led to the unionization of both General Motors and its rivals in the American automobile industry.[176]

While the First New Deal of 1933 had broad support from most sectors, the Second New Deal challenged the business community. Conservative Democrats, led by Al Smith, fought back with the American Liberty League, savagely attacking Roosevelt and equating him with socialism.[177] But Smith overplayed his hand, and his boisterous rhetoric let Roosevelt isolate his opponents and identify them with the wealthy vested interests that opposed the New Deal, strengthening Roosevelt for the 1936 landslide.[177] By contrast, labor unions, energized by labor legislation, signed up millions of new members and became a major backer of Roosevelt's re-elections in 1936, 1940, and 1944.[178]

Burns suggests that Roosevelt's policy decisions were guided more by pragmatism than ideology and that he "was like the general of a guerrilla army whose columns, fighting blindly in the mountains through dense ravines and thickets, suddenly converge, half by plan and half by coincidence, and debouch into the plain below."[179] Roosevelt argued that such apparently haphazard methodology was necessary. "The country needs and, unless I mistake its temper, the country demands bold, persistent experimentation," he wrote. "It is common sense to take a method and try it; if it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something."[180]

Election of 1936

Eight million workers remained unemployed in 1936, and though economic conditions had improved since 1932, they remained sluggish. By 1936, Roosevelt had lost the backing he once held in the business community because of his support for the NLRB and the Social Security Act.[134] The Republicans had few alternative candidates and nominated Kansas Governor Alf Landon, a little-known bland candidate whose chances were damaged by the public re-emergence of the still-unpopular Herbert Hoover.[181] While Roosevelt campaigned on his New Deal programs and continued to attack Hoover, Landon sought to win voters who approved of the goals of the New Deal but disagreed with its implementation.[182]

An attempt by Louisiana Senator Huey Long to organize a left-wing third party collapsed after Long's assassination in 1935. The remnants, helped by Father Charles Coughlin, supported William Lemke of the newly formed Union Party.[183] Roosevelt won re-nomination with little opposition at the 1936 Democratic National Convention, while his allies overcame Southern resistance to permanently abolish the long-established rule that had required Democratic presidential candidates to win the votes of two-thirds of the delegates rather than a simple majority.[lower-alpha 5]

In the election against Landon and a third-party candidate, Roosevelt won 60.8% of the vote and carried every state except Maine and Vermont.[185] The Democratic ticket won the highest proportion of the popular vote.[lower-alpha 6] Democrats also expanded their majorities in Congress, winning control of over three-quarters of the seats in each house. The election also saw the consolidation of the New Deal coalition; while the Democrats lost some of their traditional allies in big business, they were replaced by groups such as organized labor and African Americans, the latter of whom voted Democratic for the first time since the Civil War.[186] Roosevelt lost high-income voters, especially businessmen and professionals, but made major gains among the poor and minorities. He won 86 percent of the Jewish vote, 81 percent of Catholics, 80 percent of union members, 76 percent of Southerners, 76 percent of blacks in northern cities, and 75 percent of people on relief. Roosevelt carried 102 of the country's 106 cities with a population of 100,000 or more.[187]

Supreme Court fight and second term legislation

The Supreme Court became Roosevelt's primary domestic focus during his second term after the court overturned many of his programs, including NIRA. The more conservative members of the court upheld the principles of the Lochner era, which saw numerous economic regulations struck down on the basis of freedom of contract.[188] Roosevelt proposed the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, which would have allowed him to appoint an additional Justice for each incumbent Justice over the age of 70; in 1937, there were six Supreme Court Justices over the age of 70. The size of the Court had been set at nine since the passage of the Judiciary Act of 1869, and Congress had altered the number of Justices six other times throughout U.S. history.[189] Roosevelt's "court packing" plan ran into intense political opposition from his own party, led by Vice President Garner since it upset the separation of powers.[190] A bipartisan coalition of liberals and conservatives of both parties opposed the bill, and Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes broke with precedent by publicly advocating the defeat of the bill. Any chance of passing the bill ended with the death of Senate Majority Leader Joseph Taylor Robinson in July 1937.[191]

Starting with the 1937 case of West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, the court began to take a more favorable view of economic regulations. Historians have described this as, "the switch in time that saved nine."[154] That same year, Roosevelt appointed a Supreme Court Justice for the first time, and by 1941, seven of the nine Justices had been appointed by Roosevelt.[lower-alpha 7][192] After Parrish, the Court shifted its focus from judicial review of economic regulations to the protection of civil liberties.[193] Four of Roosevelt's Supreme Court appointees, Felix Frankfurter, Robert H. Jackson, Hugo Black, and William O. Douglas, were particularly influential in reshaping the jurisprudence of the Court.[194][195]

With Roosevelt's influence on the wane following the failure of the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, conservative Democrats joined with Republicans to block the implementation of further New Deal programs.[196] Roosevelt did manage to pass some legislation, including the Housing Act of 1937, a second Agricultural Adjustment Act, and the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938, which was the last major piece of New Deal legislation. The FLSA outlawed child labor, established a federal minimum wage, and required overtime pay for certain employees who work in excess of forty-hours per week.[197] He also won passage of the Reorganization Act of 1939 and subsequently created the Executive Office of the President, making it "the nerve center of the federal administrative system."[198] When the economy began to deteriorate again in mid-1937, during the onset of the recession of 1937–1938, Roosevelt launched a rhetorical campaign against big business and monopoly power in the United States, alleging that the recession was the result of a capital strike and even ordering the Federal Bureau of Investigation to look for a criminal conspiracy (of which they found none). He then asked Congress for $5 billion (equivalent to $101.78 billion in 2022) in relief and public works funding. This managed to eventually create as many as 3.3 million WPA jobs by 1938. Projects accomplished under the WPA ranged from new federal courthouses and post offices to facilities and infrastructure for national parks, bridges, and other infrastructure across the country, and architectural surveys and archaeological excavations—investments to construct facilities and preserve important resources. Beyond this, however, Roosevelt recommended to a special congressional session only a permanent national farm act, administrative reorganization, and regional planning measures, all of which were leftovers from a regular session. According to Burns, this attempt illustrated Roosevelt's inability to settle on a basic economic program.[199]

Determined to overcome the opposition of conservative Democrats in Congress, Roosevelt became involved in the 1938 Democratic primaries, actively campaigning for challengers who were more supportive of New Deal reform. Roosevelt failed badly, managing to defeat only one of the ten targeted, a conservative Democrat from New York City.[154] In the November 1938 elections, Democrats lost six Senate seats and 71 House seats, with losses concentrated among pro-New Deal Democrats. When Congress reconvened in 1939, Republicans under Senator Robert Taft formed a Conservative coalition with Southern Democrats, virtually ending Roosevelt's ability to enact his domestic proposals.[200] Despite their opposition to Roosevelt's domestic policies, many of these conservative Congressmen would provide crucial support for Roosevelt's foreign policy before and during World War II.[201]

Conservation and the environment

Roosevelt had a lifelong interest in the environment and conservation starting with his youthful interest in forestry on his family estate. Although he was never an outdoorsman or sportsman on Theodore Roosevelt's scale, his growth of the national systems was comparable.[5] When Franklin was Governor of New York, the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration was essentially a state-level predecessor of the federal Civilian Conservation Corps, with 10,000 or more men building fire trails, combating soil erosion and planting tree seedlings in marginal farmland in the state of New York.[202] As President, Roosevelt was active in expanding, funding, and promoting the National Park and National Forest systems.[203] Their popularity soared, from three million visitors a year at the start of the decade to 15.5 million in 1939.[204] The Civilian Conservation Corps enrolled 3.4 million young men and built 13,000 miles (21,000 kilometres) of trails, planted two billion trees, and upgraded 125,000 miles (201,000 kilometres) of dirt roads. Every state had its own state parks, and Roosevelt made sure that WPA and CCC projects were set up to upgrade them as well as the national systems.[205][206]

GNP and unemployment rates

| Year | Lebergott | Darby |

|---|---|---|

| 1929 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| 1932 | 23.6 | 22.9 |

| 1933 | 24.9 | 20.6 |

| 1934 | 21.7 | 16.0 |

| 1935 | 20.1 | 14.2 |

| 1936 | 16.9 | 9.9 |

| 1937 | 14.3 | 9.1 |

| 1938 | 19.0 | 12.5 |

| 1939 | 17.2 | 11.3 |

| 1940 | 14.6 | 9.5 |

Government spending increased from 8.0% of the gross national product (GNP) under Hoover in 1932 to 10.2% in 1936. The national debt as a percentage of the GNP had more than doubled under Hoover from 16% to 40% of the GNP in early 1933. It held steady at close to 40% as late as fall 1941, then grew rapidly during the war.[208] The GNP was 34% higher in 1936 than in 1932 and 58% higher in 1940 on the eve of war. That is, the economy grew 58% from 1932 to 1940 in eight years of peacetime, and then grew 56% from 1940 to 1945 in five years of wartime.[208] Unemployment fell dramatically during Roosevelt's first term. It increased in 1938 ("a depression within a depression") but continually declined after 1938.[207] Total employment during Roosevelt's term expanded by 18.31 million jobs, with an average annual increase in jobs during his administration of 5.3%.[209][210]

Foreign policy (1933–1941)

The main foreign policy initiative of Roosevelt's first term was the Good Neighbor Policy, which was a re-evaluation of U.S. policy toward Latin America. The United States frequently intervened in Latin America following the promulgation of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823, and the United States occupied several Latin American nations in the Banana Wars that occurred following the Spanish–American War of 1898. After Roosevelt took office, he withdrew U.S. forces from Haiti and reached new treaties with Cuba and Panama, ending their status as U.S. protectorates. In December 1933, Roosevelt signed the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, renouncing the right to intervene unilaterally in the affairs of Latin American countries.[211] Roosevelt also normalized relations with the Soviet Union, which the United States had refused to recognize since the 1920s.[212] He hoped to renegotiate the Russian debt from World War I and open trade relations, but no progress was made on either issue and "both nations were soon disillusioned by the accord."[213]

The rejection of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919–1920 marked the dominance of non-interventionism in American foreign policy. Despite Roosevelt's Wilsonian background, he and Secretary of State Cordell Hull acted with great care not to provoke isolationist sentiment. The isolationist movement was bolstered in the early to mid-1930s by Senator Gerald Nye and others who succeeded in their effort to stop the "merchants of death" in the U.S. from selling arms abroad.[214] This effort took the form of the Neutrality Acts; the president was refused a provision he requested giving him the discretion to allow the sale of arms to victims of aggression.[215] He largely acquiesced to Congress's non-interventionist policies in the early-to-mid 1930s.[216] In the interim, Fascist Italy under Benito Mussolini proceeded to overcome Ethiopia, and the Italians joined Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler in supporting General Francisco Franco and the Nationalist cause in the Spanish Civil War.[217] As that conflict drew to a close in early 1939, Roosevelt expressed regret in not aiding the Spanish Republicans.[218] When Japan invaded China in 1937, isolationism limited Roosevelt's ability to aid China,[219] despite atrocities like the Nanking Massacre and the USS Panay incident.[220]

Germany annexed Austria in 1938, and soon turned its attention to its eastern neighbors.[222] Roosevelt made it clear that, in the event of German aggression against Czechoslovakia, the U.S. would remain neutral.[223] After completion of the Munich Agreement and the execution of Kristallnacht, American public opinion turned against Germany, and Roosevelt began preparing for a possible war with Germany.[224] Relying on an interventionist political coalition of Southern Democrats and business-oriented Republicans, Roosevelt oversaw the expansion of U.S. airpower and war production capacity.[225]

When World War II began in September 1939 with Germany's invasion of Poland and Britain and France's subsequent declaration of war upon Germany, Roosevelt sought ways to assist Britain and France militarily.[226] Isolationist leaders like Charles Lindbergh and Senator William Borah successfully mobilized opposition to Roosevelt's proposed repeal of the Neutrality Act, but Roosevelt won Congressional approval of the sale of arms on a cash-and-carry basis.[227] He also began a regular secret correspondence with Britain's First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, in September 1939—the first of 1,700 letters and telegrams between them.[228] Roosevelt forged a close personal relationship with Churchill, who became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in May 1940.[229]

The Fall of France in June 1940 shocked the American public, and isolationist sentiment declined.[230] In July 1940, Roosevelt appointed two interventionist Republican leaders, Henry L. Stimson and Frank Knox, as Secretaries of War and the Navy, respectively. Both parties gave support to his plans for a rapid build-up of the American military, but the isolationists warned that Roosevelt would get the nation into an unnecessary war with Germany.[231] In July 1940, a group of Congressmen introduced a bill that would authorize the nation's first peacetime draft, and with the support of the Roosevelt administration, the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 passed in September. The size of the army increased from 189,000 men at the end of 1939 to 1.4 million men in mid-1941.[232] In September 1940, Roosevelt openly defied the Neutrality Acts by reaching the Destroyers for Bases Agreement, which, in exchange for military base rights in the British Caribbean Islands, gave 50 WWI American destroyers to Britain.[233]

Good Neighbor Policy

While working under President Wilson, Roosevelt had perpetuated ideas of American racial superiority by believing that the people of Latin American were uncapable of self-government.[234] However, by 1928 he had switched his point of view, becoming an advocate for cooperation.[234] In an effort to denounce past U.S. interventionism and subdue any subsequent fears of Latin Americans, Roosevelt announced on March 4, 1933, during his inaugural address, "In the field of World policy, I would dedicate this nation to the policy of the good neighbor, the neighbor who resolutely respects himself and, because he does so, respects the rights of others, the neighbor who respects his obligations and respects the sanctity of his agreements in and with a World of neighbors."[235]

In order to create a friendly relationship between the United States and Central as well as South American countries, Roosevelt sought to abstain from asserting military force in the region.[236] This position was affirmed by Cordell Hull, Roosevelt's Secretary of State at a conference of American states in Montevideo in December 1933. Hull said: "No country has the right to intervene in the internal or external affairs of another."[237] Roosevelt then confirmed the policy in December of the same year: "The definite policy of the United States from now on is one opposed to armed intervention."[238] The fact that the policy was even put into place meant that the U.S. now recognised the maturity of Latin American countries and as a result were now more open to working together, especially when it comes to maintaining the peace.[239] The policy, in the end, was yet another way for the U.S. to assert its own superiority.[240]

Election of 1940

In the months prior to the July 1940 Democratic National Convention, there was much speculation as to whether Roosevelt would run for an unprecedented third term. The president was silent, and even his closest advisors were in the dark.[241] The two-term tradition, although not yet enshrined in the Constitution,[lower-alpha 9] had been established by George Washington when he refused to run for a third term in the 1796 presidential election. Roosevelt refused to give a definitive statement as to his willingness to be a candidate again, and he even indicated to some ambitious Democrats, such as James Farley, that he would not run for a third term and that they could seek the Democratic nomination. Farley and Vice President John Garner were not pleased with Roosevelt when he ultimately made the decision to break from Washington's precedent.[134] As Germany swept through Western Europe and menaced Britain in mid-1940, Roosevelt decided that only he had the necessary experience and skills to see the nation safely through the Nazi threat. He was aided by the party's political bosses, who feared that no Democrat except Roosevelt could defeat Wendell Willkie, the popular Republican nominee.[242]

At the July 1940 Democratic Convention in Chicago, Roosevelt easily swept aside challenges from Farley and Vice President Garner, who had turned against Roosevelt in his second term because of his liberal economic and social policies.[243] To replace Garner on the ticket, Roosevelt turned to Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace of Iowa, a former Republican who strongly supported the New Deal and was popular in farm states.[244] The choice was strenuously opposed by many of the party's conservatives, who felt Wallace was too radical and "eccentric" in his private life to be an effective running mate. But Roosevelt insisted that without Wallace on the ticket he would decline re-nomination, and Wallace won the vice-presidential nomination, defeating Speaker of the House William B. Bankhead and other candidates.[243]

A late August poll taken by Gallup found the race to be essentially tied, but Roosevelt's popularity surged in September following the announcement of the Destroyers for Bases Agreement.[245] Willkie supported much of the New Deal as well as rearmament and aid to Britain but warned that Roosevelt would drag the country into another European war.[246] Responding to Willkie's attacks, Roosevelt promised to keep the country out of the war.[247] Over its last month, the campaign degenerated into a series of outrageous accusations and mud-slinging, if not by the two candidates themselves then by their respective parties.[134] Roosevelt won the 1940 election with 55% of the popular vote, 38 of the 48 states, and almost 85% of the electoral vote.[248]

Third and fourth terms (1941–1945)

World War II dominated Roosevelt's attention, with far more time devoted to world affairs than ever before. Domestic politics and relations with Congress were largely shaped by his efforts to achieve total mobilization of the nation's economic, financial, and institutional resources for the war effort. Even relationships with Latin America and Canada were structured by wartime demands. Roosevelt maintained close personal control of all major diplomatic and military decisions, working closely with his generals and admirals, the war and Navy departments, the British, and even the Soviet Union. His key advisors on diplomacy were Harry Hopkins (who was based in the White House), Sumner Welles (based in the State Department), and Henry Morgenthau Jr. at Treasury. In military affairs, Roosevelt worked most closely with Secretary Henry L. Stimson at the War Department, Army Chief of Staff George Marshall, and Admiral William D. Leahy.[249][250][251]

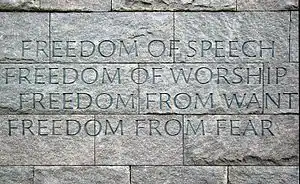

Lead-up to the war

By late 1940, re-armament was in high gear, partly to expand and re-equip the Army and Navy and partly to become the "Arsenal of Democracy" for Britain and other countries.[252] With his Four Freedoms speech in January 1941, Roosevelt laid out the case for an Allied battle for basic rights throughout the world. Assisted by Willkie, Roosevelt won Congressional approval of the Lend-Lease program, which directed massive military and economic aid to Britain, and China.[253] In sharp contrast to the loans of World War I, there would be no repayment after the war.[254] As Roosevelt took a firmer stance against Japan, Germany, and Italy, American isolationists such as Charles Lindbergh and the America First Committee vehemently attacked Roosevelt as an irresponsible warmonger.[255] When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Roosevelt agreed to extend Lend-Lease to the Soviets. Thus, Roosevelt had committed the U.S. to the Allied side with a policy of "all aid short of war."[256] By July 1941, Roosevelt authorized the creation of the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (OCIAA) to counter perceived propaganda efforts in Latin America by Germany and Italy.[257][258]

In August 1941, Roosevelt and Churchill conducted a highly secret bilateral meeting in which they drafted the Atlantic Charter, conceptually outlining global wartime and postwar goals. This would be the first of several wartime conferences;[259] Churchill and Roosevelt would meet ten more times in person.[260] Though Churchill pressed for an American declaration of war against Germany, Roosevelt believed that Congress would reject any attempt to bring the United States into the war.[261] In September, a German submarine fired on the U.S. destroyer Greer, and Roosevelt declared that the U.S. Navy would assume an escort role for Allied convoys in the Atlantic as far east as Great Britain and would fire upon German ships or submarines (U-boats) of the Kriegsmarine if they entered the U.S. Navy zone. According to historian George Donelson Moss, Roosevelt "misled" Americans by reporting the Greer incident as if it would have been an unprovoked German attack on a peaceful American ship.[262] This "shoot on sight" policy effectively declared naval war on Germany and was favored by Americans by a margin of 2-to-1.[263]

Pearl Harbor and declarations of war

After the German invasion of Poland, the primary concern of both Roosevelt and his top military staff was on the war in Europe, but Japan also presented foreign policy challenges. Relations with Japan had continually deteriorated since its invasion of Manchuria in 1931, and they had further worsened with Roosevelt's support of China.[264] With the war in Europe occupying the attention of the major colonial powers, Japanese leaders eyed vulnerable colonies such as the Dutch East Indies, French Indochina, and British Malaya.[265] After Roosevelt announced a $100 million loan (equivalent to $2.1 billion in 2022) to China in reaction to Japan's occupation of northern French Indochina, Japan signed the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy. The pact bound each country to defend the others against attack, and Germany, Japan, and Italy became known as the Axis powers.[266] Overcoming those who favored invading the Soviet Union, the Japanese Army high command successfully advocated for the conquest of Southeast Asia to ensure continued access to raw materials.[267] In July 1941, after Japan occupied the remainder of French Indochina, Roosevelt cut off the sale of oil to Japan, depriving Japan of more than 95 percent of its oil supply.[268] He also placed the Philippine military under American command and reinstated General Douglas MacArthur into active duty to command U.S. forces in the Philippines.[269]

The Japanese were incensed by the embargo and Japanese leaders became determined to attack the United States unless it lifted the embargo. The Roosevelt administration was unwilling to reverse the policy, and Secretary of State Hull blocked a potential summit between Roosevelt and Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe.[lower-alpha 10] After diplomatic efforts to end the embargo failed, the Privy Council of Japan authorized a strike against the United States.[271] The Japanese believed that the destruction of the United States Asiatic Fleet (stationed in the Philippines) and the United States Pacific Fleet (stationed at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii) was vital to the conquest of Southeast Asia.[272] On the morning of December 7, 1941, the Japanese struck the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor with a surprise attack, knocking out the main American battleship fleet and killing 2,403 American servicemen and civilians. At the same time, separate Japanese task forces attacked Thailand, British Hong Kong, the Philippines, and other targets. Roosevelt called for war in his "Infamy Speech" to Congress, in which he said: "Yesterday, December 7, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan." In a nearly unanimous vote, Congress declared war on Japan.[273] After the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, antiwar sentiment in the United States largely evaporated overnight. On December 11, 1941, Hitler and Mussolini declared war on the United States, which responded in kind.[lower-alpha 11][274]

A majority of scholars have rejected the conspiracy theories that Roosevelt, or any other high government officials, knew in advance about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.[275] The Japanese had kept their secrets closely guarded. Senior American officials were aware that war was imminent, but they did not expect an attack on Pearl Harbor.[276] Roosevelt had expected that the Japanese would attack either the Dutch East Indies or Thailand.[277]

War plans

In late December 1941, Churchill and Roosevelt met at the Arcadia Conference, which established a joint strategy between the U.S. and Britain. Both agreed on a Europe first strategy that prioritized the defeat of Germany before Japan. The U.S. and Britain established the Combined Chiefs of Staff to coordinate military policy and the Combined Munitions Assignments Board to coordinate the allocation of supplies.[278] An agreement was also reached to establish a centralized command in the Pacific theater called ABDA, named for the American, British, Dutch, and Australian forces in the theater.[279] On January 1, 1942, the United States, Britain, China, the Soviet Union, and twenty-two other countries (the Allied Powers) issued the Declaration by United Nations, in which each nation pledged to defeat the Axis powers.[280]

In 1942, Roosevelt formed a new body, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, which made the final decisions on American military strategy. Admiral Ernest J. King as Chief of Naval Operations commanded the Navy and Marines, while General George C. Marshall led the Army and was in nominal control of the Air Force, which in practice was commanded by General Hap Arnold.[281] The Joint Chiefs were chaired by Admiral William D. Leahy, the most senior officer in the military.[282] Roosevelt avoided micromanaging the war and let his top military officers make most decisions.[283] Roosevelt's civilian appointees handled the draft and procurement of men and equipment, but no civilians—not even the secretaries of War or Navy—had a voice in strategy. Roosevelt avoided the State Department and conducted high-level diplomacy through his aides, especially Harry Hopkins, whose influence was bolstered by his control of the Lend Lease funds.[284]

Nuclear program

In August 1939, Leo Szilard and Albert Einstein sent the Einstein–Szilárd letter to Roosevelt, warning of the possibility of a German project to develop nuclear weapons. Szilard realized that the recently discovered process of nuclear fission could be used to create a nuclear chain reaction that could be used as a weapon of mass destruction.[285] Roosevelt feared the consequences of allowing Germany to have sole possession of the technology and authorized preliminary research into nuclear weapons.[lower-alpha 12] After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Roosevelt administration secured the funds needed to continue research and selected General Leslie Groves to oversee the Manhattan Project, which was charged with developing the first nuclear weapons. Roosevelt and Churchill agreed to jointly pursue the project, and Roosevelt helped ensure that American scientists cooperated with their British counterparts.[287]

Wartime conferences

_(B%2526W).jpg.webp)

Roosevelt coined the term "Four Policemen" to refer to the "Big Four" Allied powers of World War II, the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and China. The "Big Three" of Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, together with Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, cooperated informally on a plan in which American and British troops concentrated in the West; Soviet troops fought on the Eastern front; and Chinese, British and American troops fought in Asia and the Pacific. The United States also continued to send aid via the Lend-Lease program to the Soviet Union and other countries. The Allies formulated strategy in a series of high-profile conferences as well as by contact through diplomatic and military channels.[288] Beginning in May 1942, the Soviets urged an Anglo-American invasion of German-occupied France in order to divert troops from the Eastern front.[289] Concerned that their forces were not yet ready for an invasion of France, Churchill and Roosevelt decided to delay such an invasion until at least 1943 and instead focus on a landing in North Africa, known as Operation Torch.[290]

In November 1943, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin met to discuss strategy and post-war plans at the Tehran Conference, where Roosevelt met Stalin for the first time.[291] At the conference, Britain and the United States committed to opening a second front against Germany in 1944, while Stalin committed to entering the war against Japan at an unspecified date. Subsequent conferences at Bretton Woods and Dumbarton Oaks established the framework for the post-war international monetary system and the United Nations, an intergovernmental organization similar to the failed League of Nations.[292] Taking up the Wilsonian mantle, Roosevelt pushed as his highest postwar priority the establishment of the United Nations. Roosevelt expected it would be controlled by Washington, Moscow, London and Beijing, and would resolve all major world problems.[293]

Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin met for a second time at the February 1945 Yalta Conference in Crimea. With the end of the war in Europe approaching, Roosevelt's primary focus was on convincing Stalin to enter the war against Japan; the Joint Chiefs had estimated that an American invasion of Japan would cause as many as one million American casualties. In return for the Soviet Union's entrance into the war against Japan, the Soviet Union was promised control of Asian territories such as Sakhalin Island. The three leaders agreed to hold a conference in 1945 to establish the United Nations, and they also agreed on the structure of the United Nations Security Council, which would be charged with ensuring international peace and security. Roosevelt did not push for the immediate evacuation of Soviet soldiers from Poland, but he won the issuance of the Declaration on Liberated Europe, which promised free elections in countries that had been occupied by Germany. Germany itself would not be dismembered but would be jointly occupied by the United States, France, Britain, and the Soviet Union.[294] Against Soviet pressure, Roosevelt and Churchill refused to consent to impose huge reparations and deindustrialization on Germany after the war.[295] Roosevelt's role in the Yalta Conference has been controversial; critics charge that he naively trusted the Soviet Union to allow free elections in Eastern Europe, while supporters argue that there was little more that Roosevelt could have done for the Eastern European countries given the Soviet occupation and the need for cooperation with the Soviet Union during and after the war.[296][297]

Course of the war