The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another, they existed between 1612 and 1947, conventionally divided into three historical periods:

- Between 1612 and 1757 the East India Company set up "factories" (trading posts) in several locations, mostly in coastal India, with the consent of the Mughal emperors, Maratha empire or local rulers. Its rivals were the merchant trading companies of Portugal, Denmark, the Netherlands, and France. By the mid-18th century three Presidency towns: Madras, Bombay and Calcutta, had grown in size.

- During the period of Company rule in India, 1757–1858, the Company gradually acquired sovereignty over large parts of India, now called "Presidencies". However, it also increasingly came under British government oversight, in effect sharing sovereignty with the Crown. At the same time, it gradually lost its mercantile privileges.

- Following the Indian Rebellion of 1857 the company's remaining powers were transferred to the Crown. Under the British Raj (1858–1947), administrative boundaries were extended to include a few other British-administered regions, such as Upper Burma. Increasingly, however, the unwieldy presidencies were broken up into "Provinces".[1]

"British India" did not include the many princely states which continued to be ruled by Indian princes, though by the 19th century under British suzerainty—their defence, foreign relations, and communications relinquished to British authority and their internal rule closely monitored.[2] At the time of Indian Independence, in 1947, there were officially 565 princely states, a few being very large although most were very small. They comprised a quarter of the population of the British Raj and two fifths of its land area, with the provinces comprising the remainders.[3]

British India (1600–1947)

In 1608, Mughal authorities allowed the English East India Company to establish a small trading settlement at Surat (now in the state of Gujarat), and this became the company's first headquarters town. It was followed in 1611 by a permanent factory at Machilipatnam on the Coromandel Coast, and in 1612 the company joined other already established European trading companies in Bengal in trade.[4] However, the power of the Mughal Empire declined from 1707, first at the hands of the Marathas and later due to invasion from Persia (1739) and Afghanistan (1761); after the East India Company's victories at the Battle of Plassey (1757), and Battle of Buxar (1764)—both within the Bengal Presidency established in 1765—and the abolition of local rule (Nizamat) in Bengal in 1793, the company gradually began to formally expand its territories across India.[5] By the mid-19th century, and after the three Anglo-Maratha Wars the East India Company had become the paramount political and military power in south Asia, its territory held in trust for the British Crown.[6]

Company rule in Bengal (after 1793) was terminated by the Government of India Act 1858, following the events of the Bengal Rebellion of 1857.[6] Henceforth known as British India, it was thereafter directly ruled as a colonial possession of the United Kingdom, and India was officially known after 1876 as the Indian Empire.[7] India was divided into British India, regions that were directly administered by the British, with acts established and passed in the British parliament,[8] and the princely states,[9] ruled by local rulers of different ethnic backgrounds. These rulers were allowed a measure of internal autonomy in exchange for recognition of British suzerainty. British India constituted a significant portion of India both in area and population; in 1910, for example, it covered approximately 54% of the area and included over 77% of the population.[10] In addition, there were Portuguese and French exclaves in India. Independence from British rule was achieved in 1947 with the formation of two nations, the Dominions of India and Pakistan, the latter including East Bengal, present-day Bangladesh.

The term British India also applied to Burma for a shorter time period: beginning in 1824, a small part of Burma, and by 1886, almost two thirds of Burma had been made part of British India.[8] This arrangement lasted until 1937, when Burma was reorganized as a separate British colony. British India did not apply to other countries in the region, such as Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), which was a British Crown colony, or the Maldive Islands, which were a British protectorate. At its greatest extent, in the early 20th century, the territory of British India extended as far as the frontiers of Persia in the west; Afghanistan in the northwest; Nepal in the north, Tibet in the northeast; and China, French Indochina and Siam in the east. It also included the Aden Province in the Arabian Peninsula.[11]

Administration under the East India Company (1793–1858)

The East India Company, which was incorporated on 31 December 1600, established trade relations with Indian rulers in Masulipatam on the east coast in 1611 and Surat on the west coast in 1612.[12] The company rented a small trading outpost in Madras in 1639.[12] Bombay, which was ceded to the British Crown by Portugal as part of the wedding dowry of Catherine of Braganza in 1661, was in turn granted to the East India Company to be held in trust for the Crown.[12]

Meanwhile, in eastern India, after obtaining permission from the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan to trade with Bengal, the company established its first factory at Hoogly in 1640.[12] Almost a half-century later, after Mughal Emperor Aurengzeb forced the company out of Hooghly for its tax evasion, Job Charnock was tenant of three small villages, later renamed Calcutta, in 1686, making it the company's new headquarters.[12] By the mid-18th century, the three principal trading settlements including factories and forts, were then called the Madras Presidency (or the Presidency of Fort St. George), the Bombay Presidency, and the Bengal Presidency (or the Presidency of Fort William)—each administered by a governor.[13]

The presidencies

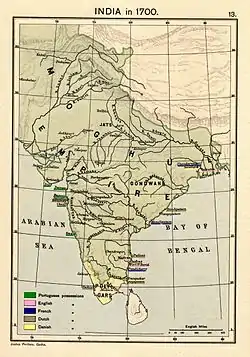

The Indian peninsula in 1700, showing the Mughal Empire and the European trading settlements.

The Indian peninsula in 1700, showing the Mughal Empire and the European trading settlements. The Indian peninsula in 1760, three years after the Battle of Plassey, showing the Maratha Empire and other prominent political states.

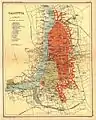

The Indian peninsula in 1760, three years after the Battle of Plassey, showing the Maratha Empire and other prominent political states..jpg.webp) The presidency town of Madras in a 1908 map. Madras was established as Fort St. George in 1640.

The presidency town of Madras in a 1908 map. Madras was established as Fort St. George in 1640..jpg.webp) The presidency town of Bombay (shown here in a 1908 map) was established in 1684.

The presidency town of Bombay (shown here in a 1908 map) was established in 1684. The presidency town of Calcutta (shown here in a 1908 map) was established in 1690 as Fort William.

The presidency town of Calcutta (shown here in a 1908 map) was established in 1690 as Fort William.

- Madras Presidency: established 1640.

- Bombay Presidency: East India Company's headquarters moved from Surat to Bombay (Mumbai) in 1687.

- Bengal Presidency: established 1690.

After Robert Clive's victory in the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the puppet government of a new Nawab of Bengal, was maintained by the East India Company.[14] However, after the invasion of Bengal by the Nawab of Oudh in 1764 and his subsequent defeat in the Battle of Buxar, the Company obtained the Diwani of Bengal, which included the right to administer and collect land-revenue (land tax) in Bengal, the region of present-day Bangladesh, West Bengal, Jharkhand and Bihar beginning from 1772 as per the treaty signed in 1765.[14] By 1773, the Company obtained the Nizāmat of Bengal (the "exercise of criminal jurisdiction") and thereby full sovereignty of the expanded Bengal Presidency.[14] During the period, 1773 to 1785, very little changed; the only exceptions were the addition of the dominions of the Raja of Banares to the western boundary of the Bengal Presidency, and the addition of Salsette Island to the Bombay Presidency.[15]

Portions of the Kingdom of Mysore were annexed to the Madras Presidency after the Third Anglo-Mysore War ended in 1792. Next, in 1799, after the defeat of Tipu Sultan in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War more of his territory was annexed to the Madras Presidency.[15] In 1801, Carnatic, which had been under the suzerainty of the company, began to be directly administered by it as a part of the Madras Presidency.[16]

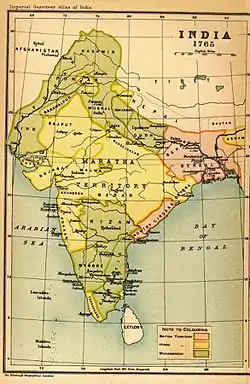

Map of India in 1765.

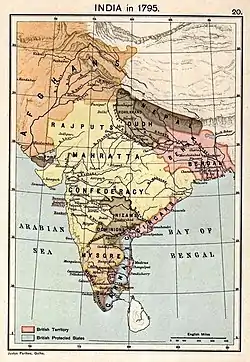

Map of India in 1765. Map of India in 1795.

Map of India in 1795. Map of India in 1805.

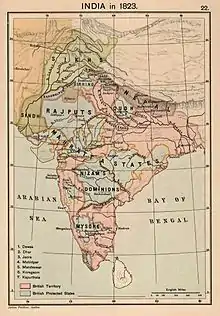

Map of India in 1805. Map of India in 1823.

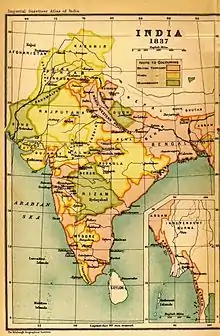

Map of India in 1823. Map of India in 1837.

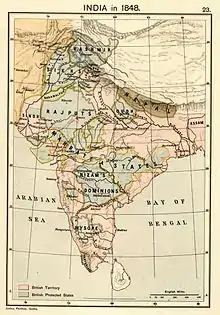

Map of India in 1837. Map of India in 1848.

Map of India in 1848. Map of India in 1857.

Map of India in 1857. Expansion of British Bengal and Burma.

Expansion of British Bengal and Burma.

The new provinces

By 1851, the East India Company's vast and growing holdings across the sub-continent were still grouped into just four main territories:

- Bengal Presidency with its capital at Calcutta

- Bombay Presidency with its capital at Bombay

- Madras Presidency with its capital at Madras

- North-Western Provinces with the seat of the lieutenant-governor at Agra. The original seat of government was at Allahabad, then at Agra from 1834 to 1868. In 1833, an Act of the British Parliament (statute 3 and 4, William IV, cap. 85) promulgated the elevation the Ceded and Conquered Provinces to the new Presidency of Agra, and the appointment of a new governor for the latter, but the plan was never carried out. In 1835 another act of Parliament (statute 5 and 6, William IV, cap. 52) renamed the region the North-Western Provinces, this time to be administered by a lieutenant-governor, the first of whom, Sir Charles Metcalfe, would be appointed in 1836.[17]

By the time of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, and the end of Company rule, the developments could be summarised as follows:

- Bombay Presidency: expanded after the Anglo-Maratha Wars.

- Madras Presidency: expanded in the mid-to-late 18th century Carnatic Wars and Anglo-Mysore Wars.

- Bengal Presidency: expanded after the battles of Plassey (1757) and Buxar (1764), and after the Second and Third Anglo-Maratha Wars.

- Penang: became a residency within the Bengal Presidency in 1786, the fourth presidency of India in 1805, part of the presidency of the Straits Settlements until 1830, again part of a residency within the Bengal Presidency when the Straits Settlements became so, and finally separated from British India in 1867.

- Ceded and Conquered Provinces: established in 1802 within the Bengal Presidency. Proposed to be renamed the Presidency of Agra under a governor in 1835, but proposal not implemented.

- Ajmer-Merwara: ceded by Sindhia of Gwalior in 1818 at the conclusion of the Third Anglo-Maratha War.

- Coorg: Annexed in 1834.

- North-Western Provinces: established as a lieutenant-governorship in 1836 from the erstwhile Ceded and Conquered Provinces.

- Sind: annexed to the Bombay Presidency in 1843.

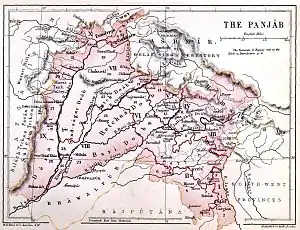

- Punjab Province: Established in 1849 from territories captured in the First and Second Anglo-Sikh Wars.

- Nagpur Province: Created in 1853 from the princely state of Nagpur, seized by the doctrine of lapse. Merged into the Central Provinces in 1861.

- Oudh State annexed in 1856 and governed thereafter until 1905 as a chief commissionership, as a part of North-Western Provinces and Oudh.

North-Western Provinces, constituted in 1836 from erstwhile Ceded and Conquered Provinces.

North-Western Provinces, constituted in 1836 from erstwhile Ceded and Conquered Provinces. Punjab annexed in 1849.

Punjab annexed in 1849. Oudh annexed in 1856.

Oudh annexed in 1856.

Administration under the Crown (1858–1947)

Historical background

The British Raj began with the idea of the presidencies as the centres of government. Until 1834, when a General Legislative Council was formed, each presidency under its governor and council was empowered to enact a code of so-called 'regulations' for its government. Therefore, any territory or province that was added by conquest or treaty to a presidency came under the existing regulations of the corresponding presidency. However, in the case of provinces that were acquired but were not annexed to any of the three presidencies, their official staff could be provided as the governor-general pleased, and was not governed by the existing regulations of the Bengal, Madras, or Bombay presidencies. Such provinces became known as 'non-regulation provinces' and up to 1833 no provision for a legislative power existed in such places.[18] The same two kinds of management applied for districts. Thus Ganjam and Vizagapatam were non-regulation districts.[19] Non-regulation provinces included:

- Ajmer Province (Ajmer-Merwara)

- Cis-Sutlej states

- Saugor and Nerbudda Territories

- North-East Frontier (Assam)

- Cooch Behar

- South-West Frontier (Chota Nagpur)

- Jhansi State

- Kumaon Province

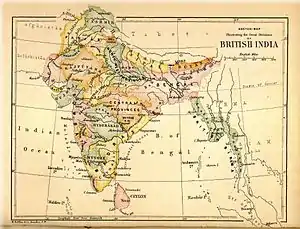

British India in 1880: This map incorporates the provinces of British India, the Princely States and the legally non-Indian Crown Colony of Ceylon.

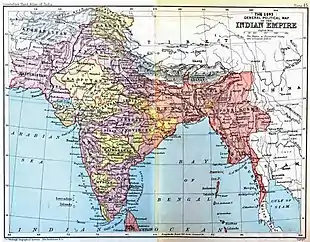

British India in 1880: This map incorporates the provinces of British India, the Princely States and the legally non-Indian Crown Colony of Ceylon. The Indian Empire in 1893 after the annexation of Upper Burma and incorporation of Baluchistan.

The Indian Empire in 1893 after the annexation of Upper Burma and incorporation of Baluchistan. The Indian Empire in 1907 during the partition of Bengal (1905–1912).

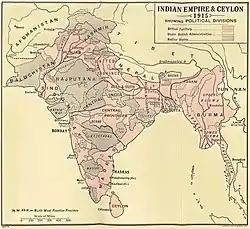

The Indian Empire in 1907 during the partition of Bengal (1905–1912). The Indian Empire in 1915 after the reunification of Bengal, the creation of the new province of Bihar and Orissa, and the re-establishment of Assam.

The Indian Empire in 1915 after the reunification of Bengal, the creation of the new province of Bihar and Orissa, and the re-establishment of Assam.

Regulation provinces

- Central Provinces: Created in 1861 from Nagpur Province and the Saugor and Nerbudda Territories. Berar was added to the province in 1903, and was renamed the Central Provinces and Berar in 1936.

- Burma: Lower Burma annexed 1852, established as a province in 1862, Upper Burma incorporated in 1886. Separated from British India in 1937 to become administered independently by the newly established British Government Burma Office.

- Assam: separated from Bengal in 1874 as the North-East Frontier non-regulation province. Incorporated into the new province of Eastern Bengal and Assam in 1905. Re-established as a province in 1912.

- Andaman and Nicobar Islands: established as a province in 1875.

- Baluchistan: Organised into a province in 1887.

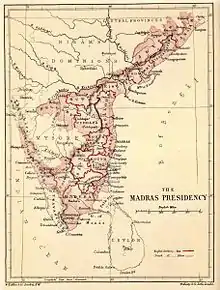

Madras Presidency shown in an 1880 map.

Madras Presidency shown in an 1880 map. Bombay Presidency in an 1880 map.

Bombay Presidency in an 1880 map. Bengal Presidency in 1880.

Bengal Presidency in 1880. An 1880 map of Central Provinces. The province had been constituted in 1861.

An 1880 map of Central Provinces. The province had been constituted in 1861. 1908 map of Central Provinces and Berar. Berar was included in 1903.

1908 map of Central Provinces and Berar. Berar was included in 1903. Beluchistan, shown as an independent kingdom along with Afghanistan and Turkestan, in an 1880 map.

Beluchistan, shown as an independent kingdom along with Afghanistan and Turkestan, in an 1880 map. Baluchistan in 1908: the Districts and Agencies of British Baluchistan are shown alongside the States, mostly: Kalat.

Baluchistan in 1908: the Districts and Agencies of British Baluchistan are shown alongside the States, mostly: Kalat.

- North-West Frontier Province: created in 1901 from the north-western districts of Punjab Province.

- Eastern Bengal and Assam: created in 1905 upon the partition of Bengal, together with the former province of Assam. Re-merged with Bengal in 1912, with north-eastern part re-established as the province of Assam.

- Bihar and Orissa: separated from Bengal in 1912. Renamed Bihar in 1936 when Orissa became a separate province.

- Delhi: Separated from Punjab in 1912, when it became the capital of British India.

- Orissa: Separate province by carving out certain portions from the Bihar-Orissa Province and the Madras Province in 1936.

- Sind: Separated from Bombay in 1936.

- Panth-Piploda: made a province in 1942, from territories ceded by a native ruler.

Major provinces

At the turn of the 20th century, British India consisted of eight provinces that were administered either by a governor or a lieutenant-governor. The following table lists their areas and populations (but does not include those of the dependent native states):[20] During the partition of Bengal (1905–1912), a new lieutenant-governor's province of Eastern Bengal and Assam existed. In 1912, the partition was partially reversed, with the eastern and western halves of Bengal re-united and the province of Assam re-established; a new lieutenant-governor's province of Bihar and Orissa was also created.

| Province of British India[20] | Area (in thousands of square miles) | Population | Chief administrative officer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burma | 170 | 9,000,000 | Lieutenant-Governor |

| Bengal | 151 | 75,000,000 | Lieutenant-Governor |

| Madras | 142 | 38,000,000 | Governor-in-Council |

| Bombay | 123 | 19,000,000 | Governor-in-Council |

| United Provinces | 107 | 48,000,000 | Lieutenant-Governor |

| Central Provinces and Berar | 104 | 13,000,000 | Chief Commissioner |

| Punjab | 97 | 20,000,000 | Lieutenant-Governor |

| Assam | 49 | 6,000,000 | Chief Commissioner |

Minor provinces

In addition, there were a few provinces that were administered by a chief commissioner:[21]

| Minor Province[21] | Area (in thousands of square miles) | Population (in thousands of inhabitants) | Chief administrative officer |

|---|---|---|---|

| North-West Frontier Province | 16 | 2,125 | Chief Commissioner |

| Baluchistan | 46 | 308 | British political agent in Baluchistan served as ex officio Chief Commissioner |

| Coorg | 1.6 | 181 | British Resident in Mysore served as ex officio Chief Commissioner |

| Ajmer-Merwara | 2.7 | 477 | British political agent in Rajputana served as ex officio Chief Commissioner |

| Andaman and Nicobar Islands | 3 | 25 | Chief Commissioner |

Aden

- As the Settlement of Aden, a dependency of the Bombay Presidency from 1839 to 1932; became a chief commissioner's province in 1932; separated from India and made the Crown Colony of Aden in 1937.

Partition and independence (1947)

At the time of independence in 1947, British India had 17 provinces:

Upon the partition of British India into the Dominion of India and Dominion of Pakistan, eleven provinces (Ajmer-Merwara-Kekri, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Bihar, Bombay, Central Provinces and Berar, Coorg, Delhi, Madras, Panth-Piploda, Orissa, and the United Provinces) joined India, three (Baluchistan, North-West Frontier and Sindh) joined Pakistan, and three (Punjab, Bengal and Assam) were partitioned between India and Pakistan.

In 1950, after the new Indian constitution was adopted, the provinces in India were replaced by redrawn states and union territories. Pakistan, however, retained its five provinces, one of which, East Bengal, was renamed East Pakistan in 1956 and became the independent nation of Bangladesh in 1971.

See also

Citations

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1908, p. 5 Quote: "The history of British India falls ... into three periods. From the beginning of the 17th to the middle of the 18th century, the East India Company is a trading corporation, existing on the sufferance of the native powers, and in rivalry with the merchant companies of Holland and France. During the next century, the Company acquires and consolidates its dominion, shares its sovereignty in increasing proportions with the Crown, and gradually loses its mercantile privileges and functions. After the Mutiny of 1857, the remaining powers of the Company are transferred to the Crown ..."

- ↑ Copland, Ian (21–27 February 2004). "Princely States and the Raj: Review of Sovereign Spheres: Princes, Education and Empire in Colonial India by Manu Bhagavan". Economic and Political Weekly. 39 (8): 807–809. JSTOR 4414671.

- ↑ S. H. Steinberg, ed. (1949), "India", The Statesman's Year-Book: Statistical and Historical Annual of the States of the World for the Year 1949, Macmillan and Co, p. 122, ISBN 9780230270787

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. II 1908, pp. 452–472

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. II 1908, pp. 473–487

- 1 2 Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. II 1908, pp. 488–514

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. II 1908, pp. 514–530

- 1 2 Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1908, pp. 46–57

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1908, pp. 58–103

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1908, pp. 59–61

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1908, pp. 104–125

- 1 2 3 4 5 Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1908, p. 6

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1908, p. 7

- 1 2 3 Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1908, p. 9

- 1 2 Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1908, p. 10

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1908, p. 11

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India, vol. V, 1908

- ↑ "Full text of "The land systems of British India : being a manual of the land-tenures and of the systems of land-revenue administration prevalent in the several provinces"". archive.org. 1892.

- ↑ Geography of India 1870

- 1 2 Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1908, p. 46

- 1 2 Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1908, p. 56

General references

- The Imperial Gazetteer of India (26 vol, 1908–31), highly detailed description of all of India in 1901. online edition

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. II (1908), The Indian Empire, Historical, Published under the authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press. Pp. xxxv, 1 map, 573

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III (1908), "Chapter X: Famine", The Indian Empire, Economic, Published under the authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press. Pp. xxxvi, 1 map, 520, pp. 475–502

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV (1908), The Indian Empire, Administrative, Published under the authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press. Pp. xxx, 1 map, 552

Further reading

- Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar (2004). From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India. New Delhi and London: Orient Longmans. Pp. xx, 548. ISBN 81-250-2596-0.

- Brown, Judith M. (1994) [First published 1985]. Modern India: The Origins of an Asian Democracy (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. Pp. xiii, 474. ISBN 0-19-873113-2.

- Copland, Ian (2001). India 1885–1947: The Unmaking of an Empire (Seminar Studies in History Series). Harlow and London: Pearson Longmans. Pp. 160. ISBN 0-582-38173-8.

- Harrington, Jack (2010). Sir John Malcolm and the Creation of British India. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-10885-1.

- Judd, Dennis (2004). The Lion and the Tiger: The Rise and Fall of the British Raj, 1600–1947. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. xiii, 280. ISBN 0-19-280358-1.

- Majumdar, R. C.; Raychaudhuri, H. C.; Datta, Kalikinkar (1950). An Advanced History of India. London: Macmillan and Company Limited. 2nd edition. Pp. xiii, 1122, 7 maps, 5 coloured maps.

- Markovits, Claude, ed. (2005). A History of Modern India 1480–1950 (Anthem South Asian Studies). Anthem Press. Pp. 607. ISBN 1-84331-152-6.

- Metcalf, Barbara; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006). A Concise History of Modern India (Cambridge Concise Histories). Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. Pp. xxxiii, 372. ISBN 0-521-68225-8..

- Mill, James (1820). The History of British India, in six volumes. London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 3rd edition, 1826.

- Peers, Douglas M. (2006). India under Colonial Rule 1700–1885. Harlow and London: Pearson Longmans. Pp. xvi, 163. ISBN 0-582-31738-X.

- Riddick, John F. (2006). The history of British India: a chronology. Praeger. ISBN 9780313322808.

- Riddick, John F. (1998). Who Was Who in British India.

- Sarkar, Sumit (1983). Modern India: 1885–1947. Delhi: Macmillan India Ltd. Pp. xiv, 486. ISBN 0-333-90425-7.

- Seymour, William. "The Indian States under the British Crown" History Today. (Dec 1967), Vol. 17 Issue 12, pp 819–827 online; covers 1858 to 1947.

- Smith, Vincent A. (1921). India in the British Period: Being Part III of the Oxford History of India. Oxford: At the Clarendon Press. 2nd edition. Pp. xxiv, 316 (469–784).

- Spear, Percival (1990) [First published 1965]. A History of India, Volume 2: From the sixteenth century to the twentieth century. New Delhi and London: Penguin Books. Pp. 298. ISBN 0-14-013836-6.

External links

- Cahoon, Ben. "Provinces of British India". WorldStatesmen.org. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- Statistical abstracts relating to British India, from 1840 to 1920 at uchicago.edu

- Digital Colonial Documents (India) Homepage at latrobe.edu.au

- Collection of early 20th century photographs of the cities of Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras with other interesting Indian locations from the magazine, India Illustrated, at the University of Houston Digital Library

- Coins of British India