Pont du Gard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 43°56′50″N 04°32′08″E / 43.94722°N 4.53556°E |

| Carries | Roman aqueduct of Nîmes |

| Crosses | Gardon River |

| Locale | Vers-Pont-du-Gard, Gard, France |

| Maintained by | Public Association of Cultural Cooperation (since 2003) |

| Website | pontdugard |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Arch bridge |

| Material | Shelly limestone |

| Total length |

|

| Width |

|

| Height |

|

| No. of spans |

|

| Piers in water | 5 |

| History | |

| Construction end | c. 40–60 AD |

| Construction cost | 30 million sesterces (est.) |

| Closed | c. 6th century |

| Official name | Pont du Gard (Roman Aqueduct) |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, iv |

| Designated | 1985 (9th session) |

| Reference no. | 344 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Designated | 1840 |

| Reference no. | PA00103291 |

| Location | |

| References | |

| [1][2] | |

The Pont du Gard is an ancient Roman aqueduct bridge built in the first century AD to carry water over 50 km (31 mi) to the Roman colony of Nemausus (Nîmes).[3] It crosses the river Gardon near the town of Vers-Pont-du-Gard in southern France. The Pont du Gard is the tallest of all Roman aqueduct bridges, as well as one of the best preserved. It was added to UNESCO's list of World Heritage sites in 1985 because of its exceptional preservation, historical importance, and architectural ingenuity.[4]

Description

The bridge has three tiers of arches made from Shelly limestone and stands 48.8 m (160 ft) high. The aqueduct formerly carried an estimated 40,000 m3 (8,800,000 imp gal; 11,000,000 US gal) of water a day over 50 km (31 mi) to the fountains, baths and homes of the citizens of Nîmes. The structure's precise construction allowed an average gradient of 1 cm (0.39 in) in 182.4 m (598 ft). It may have been in use as late as the 6th century, with some parts used for significantly longer, but lack of maintenance after the 4th century led to clogging by mineral deposits and debris that eventually stopped the flow of water.

After the Roman Empire collapsed and the aqueduct fell into disuse, the Pont du Gard remained largely intact with a secondary function as a toll bridge. For centuries the local lords and bishops were responsible for its upkeep, with a right to levy tolls on travellers using it to cross the river. Over time, some of its stone blocks were looted, and serious damage was inflicted in the 17th century. It attracted increasing attention starting in the 18th century, and became an important tourist destination. A series of renovations between the 18th and 21st centuries, commissioned by local authorities and the French state, culminated in 2000 with opening of a new visitor centre and removal of traffic and buildings from the bridge and area immediately around it. Today it is one of France's most popular tourist attractions, and has attracted the attention of a succession of literary and artistic visitors.

Route of the Nîmes aqueduct

The location of Nemausus (Nîmes) was somewhat inconvenient when it came to providing a water supply. Plains lie to the city's south and east, where any sources of water would be at too low an altitude to be able to flow to the city, while the hills to the west made a water supply route too difficult from an engineering point of view. The only real alternative was to look to the north and in particular to the area around Ucetia (Uzès), where there are natural springs.[5]

The Nîmes aqueduct was built to channel water from the springs of the Fontaine d'Eure near Uzès to the castellum divisorum (repartition basin) in Nemausus. From there, it was distributed to fountains, baths and private homes around the city. The straight-line distance between the two is only about 20 km (12 mi), but the aqueduct takes a winding route measuring around 50 km (31 mi).[6] This was necessary to circumvent the southernmost foothills of the Massif Central, known as the Garrigues de Nîmes. They are difficult to cross, as they are covered in dense vegetation and garrigue and indented by deep valleys.[7] It was impractical for the Romans to attempt to tunnel through the hills, as it would have required a tunnel of between 8 and 10 kilometres (5 and 6 mi), depending on the starting point. A roughly V-shaped course around the eastern end of the Garrigues de Nîmes was therefore the only practical way of transporting the water from the spring to the city.

The Fontaine d'Eure, at 76 m (249 ft) above sea level, is only 17 m (56 ft) higher than the repartition basin in Nîmes, but this provided a sufficient gradient to sustain a steady flow of water to the 50,000 inhabitants of the Roman city. The aqueduct's average gradient is only 1 in 3,000. It varies widely along its course, but is as little as 1 in 20,000 in some sections. The Pont du Gard itself descends 2.5 cm (0.98 in) in 456 m (1,496 ft), a gradient of 1 in 18,241.[8] The average gradient between the start and end of the aqueduct is far shallower than was usual for Roman aqueducts – only about a tenth of the average gradient of some of the aqueducts in Rome.[9]

The reason for the disparity in gradients along the aqueduct's route is that a uniform gradient would have meant that the Pont du Gard would have been infeasibly high, given the limitations of the technology of the time. By varying the gradient along the route, the aqueduct's engineers were able to lower the height of the bridge by 6 metres (20 ft) to 48.77 metres (160.0 ft) above the river – still exceptionally high by Roman standards, but within acceptable limits. This height limit governed the profile and gradients of the entire aqueduct, but it came at the price of creating a "sag" in the middle of the aqueduct. The gradient profile before the Pont du Gard is relatively steep, descending at 0.67 metres (2 ft 2 in) per kilometre, but thereafter it descends by only 6 metres (20 ft) over the remaining 25 kilometres (16 mi). In one section, the winding route between the Pont du Gard and St Bonnet required an extraordinary degree of accuracy from the Roman engineers, who had to allow for a fall of only 7 millimetres (0.28 in) per 100 metres (330 ft) of the conduit.[10]

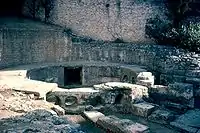

It is estimated that the aqueduct supplied the city with around 40,000 cubic metres (8,800,000 imp gal) of water a day[11] that took nearly 27 hours to flow from the source to the city.[12] The water arrived in the castellum divisorum at Nîmes – an open, shallow, circular basin 5.5 m in diameter by 1 m deep. It would have been surrounded by a balustrade within some sort of enclosure, probably under some kind of small but elaborate pavilion. When it was excavated, traces of a tiled roof, Corinthian columns and a fresco decorated with fish and dolphins were discovered in a fragmentary condition.[13] The aqueduct water entered through an opening 1.2 metres (3 ft 11 in) wide, and ten large holes in the facing wall, each 40 centimetres (16 in) wide, directed the water into the city's main water pipes. Three large drains were also located in the floor, possibly to enable the nearby amphitheatre to be flooded rapidly to enable naumachia (mock naval battles) to be held.[14]

The spring still exists and is now the site of a small modern pumping station. Its water is pure but high in dissolved calcium carbonate leached out of the surrounding limestone. This presented the Romans with significant problems in maintaining the aqueduct, as the carbonates precipitated out of the water during its journey through the conduit. This caused the flow of the aqueduct to become progressively reduced by deposits of calcareous sinter.[15] Another threat was posed by vegetation penetrating the stone lid of the channel. As well as obstructing the flow of the water, dangling roots introduced algae and bacteria that decomposed in a process called biolithogenesis, producing concretions within the conduit. It required constant maintenance by circitores, workers responsible for the aqueduct's upkeep, who crawled along the conduit scrubbing the walls clean and removing any vegetation.[16]

Much of the Nîmes aqueduct was built underground, as was typical of Roman aqueducts. It was constructed by digging a trench in which a stone channel was built and enclosed by an arched roof of stone slabs, which was then covered with earth. Some sections of the channel are tunnelled through solid rock. In all, 35 km (22 mi) of the aqueduct was constructed below the ground.[17] The remainder had to be carried on the surface through conduits set on a wall or on arched bridges. Some substantial remains of the above-ground works can still be seen today, such as the so-called "Pont Rue" that stretches for hundreds of metres around Vers and still stands up to 7.5 m (25 ft) high.[18] Other surviving parts include the Pont de Bornègre, three arches carrying the aqueduct 17 m (56 ft) across a stream; the Pont de Sartanette, near the Pont du Gard, which covers 32 m (105 ft) across a small valley; and three sections of aqueduct tunnel near Sernhac, measuring up to 66 m (217 ft) long.[19] However, the Pont du Gard is by far the best-preserved section of the entire aqueduct.

Description of the bridge

Built on three levels, the Pont is 49 m (161 ft) high above the river at low water and 274 m (899 ft) long. Its width varies from 9 m (30 ft) at the bottom to 3 m (9.8 ft) at the top.[21] The three levels of arches are recessed, with the main piers in line one above another. The span of the arches varies slightly, as each was constructed independently to provide flexibility to protect against subsidence. Each level has a differing number of arches:[20][22]

| Level | Number of arches | Length of level | Thickness of piers | Height of arches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower (1st row) | 6 | 142 m (466 ft) | 6 m (20 ft) | 22 m (72 ft) |

| Middle (2nd row) | 11 | 242 m (794 ft) | 4 m (13 ft) | 20 m (66 ft) |

| Upper (3rd row) | 35 (originally 47) | 275 m (902 ft) | 3 m (9.8 ft) | 7 m (23 ft) |

The first level of the Pont du Gard adjoins a road bridge that was added in the 18th century. The water conduit or specus, which is about 1.8 m (6 ft) high and 1.2 m (4 ft) wide, is carried at the top of the third level. The upper levels of the bridge are slightly curved in the upstream direction. It was long believed that the engineers had designed it this way deliberately to strengthen the bridge's structure against the flow of water, like a dam wall. However, a microtopographic survey carried out in 1989 showed that the bend is caused by the stone expanding and contracting by about 5 mm (0.20 in) a day under the heat of the sun. Over the centuries, this process has produced the current deformation.[23]

The Pont du Gard was constructed largely without the use of mortar or clamps. It contains an estimated 50,400 tons of limestone with a volume of some 21,000 m3 (740,000 cu ft); some of the individual blocks weigh up to 6 tons.[24] Most of the stone was extracted from the local quarry of Estel located approximately 700 metres (2,300 ft) downstream, on the banks of the Gardon River.[25][26] The coarse-grained soft reddish shelly limestone, known locally as "Pierre de Vers", lends itself very well to dimension stone production. The blocks were precisely cut to fit perfectly together by friction and gravity, eliminating the need for mortar.[11] The builders also left inscriptions on the stonework conveying various messages and instructions. Many blocks were numbered and inscribed with the required locations, such as fronte dextra or fronte sinistra (front right or front left), to guide the builders.[27]

The method of construction is fairly well understood by historians.[28][29][30] The patron of the aqueduct – a rich individual or the city of Nîmes itself – would have hired a large team of contractors and skilled labourers. A surveyor or mensor planned the route using a groma for sighting, the chorobates for levelling, and a set of measuring poles five or ten Roman feet long. His figures and perhaps diagrams were recorded on wax tablets, later to be written up on scrolls. The builders may have used templates to guide them with tasks that required a high degree of precision, such as carving the standardised blocks from which the water conduit was constructed.[31]

The builders would have made extensive use of cranes and block and tackle pulleys to lift the stones into place. Much of the work could have been done using simple sheers operated by a windlass. For the largest blocks, a massive human-powered treadmill would have been used; such machines were still being used in the quarries of Provence until as late as the start of the 20th century.[31] A complex scaffold was erected to support the bridge as it was being built. Large blocks were left protruding from the bridge to support the frames and scaffolds used during construction.[22] The aqueduct as a whole would have been a very expensive undertaking; Émile Espérandieu estimated the cost to be over 30 million sesterces,[31][32] equivalent to 50 years' pay for 500 new recruits in a Roman legion.[19]

Stonework on the Pont du Gard, showing the protruding blocks that were used to support the scaffolding

Stonework on the Pont du Gard, showing the protruding blocks that were used to support the scaffolding The underside of an arch on the second tier of the Pont du Gard. Note the missing stonework atop the aqueduct.

The underside of an arch on the second tier of the Pont du Gard. Note the missing stonework atop the aqueduct. The road bridge adjacent to the aqueduct. Pedestrians are shown for scale.

The road bridge adjacent to the aqueduct. Pedestrians are shown for scale. Interior of the water conduit of the Pont du Gard

Interior of the water conduit of the Pont du Gard The water tank or castellum divisorum at Nîmes, into which the aqueduct emptied. The round holes were where the city's water supply pipes connected to the tank.

The water tank or castellum divisorum at Nîmes, into which the aqueduct emptied. The round holes were where the city's water supply pipes connected to the tank. Pont du Gard seen from the river Gardon

Pont du Gard seen from the river Gardon

Although the exterior of the Pont du Gard is rough and relatively unfinished, the builders took care to ensure that the interior of the water conduit was as smooth as possible so that the flow of water would not be obstructed. The walls of the conduit were constructed from dressed masonry and the floor from concrete. Both were covered with a stucco incorporating minute shards of pottery and tile. It was painted with olive oil and covered with maltha, a mixture of slaked lime, pork grease and the viscous juice of unripe figs. This produced a surface that was both smooth and durable.[33]

Although the Pont du Gard is renowned for its appearance, its design is not optimal as the technique of stacking arches on top of each other is clumsy and inefficient (and therefore expensive) in the amount of materials it requires. Later aqueducts had a more sophisticated design, making greater use of concrete to reduce their volume and cost of construction. The Aqueduct bridge of Segovia and the Pont de les Ferreres are of roughly similar length but use far fewer arches. Roman architects were eventually able to do away with "stacking" altogether. The Acueducto de los Milagros in Mérida, Spain and the Chabet Ilelouine aqueduct bridge, near Cherchell, Algeria[34] utilise tall, slender piers, constructed from top to bottom with concrete-faced masonry and brick.[35]

History

The construction of the aqueduct has long been credited to the Roman emperor Augustus' son-in-law and aide, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, around the year 19 BC. At the time, he was serving as aedile, the senior magistrate responsible for managing the water supply of Rome and its colonies. Espérandieu, writing in 1926, linked the construction of the aqueduct with Agrippa's visit to Narbonensis in that year.[7] Newer excavations suggest the construction may have taken place between 40 and 60 AD. Tunnels dating from the time of Augustus had to be bypassed by the builders of the Nîmes aqueduct, and coins discovered in the outflow in Nîmes are no older than the reign of the emperor Claudius (41–54 AD). On this basis, a team led by Guilhem Fabre has argued that the aqueduct must have been completed around the middle of the 1st century AD.[36] It is believed to have taken about fifteen years to build, employing between 800 and 1,000 workers.[37]

From the 4th century onwards, the aqueduct's maintenance was neglected as successive waves of invaders disrupted the region.[33] It became clogged with debris, encrustations and plant roots, greatly reducing the flow of the water. The resulting deposits in the conduit, consisting of layers of dirt and organic material, are up to 50 cm (20 in) thick on each wall.[38] An analysis of the deposits originally suggested that it had continued to supply water to Nîmes until as late as the 9th century,[39] but more recent investigations suggest that it had gone out of use by about the sixth century, though parts of it may have continued to be used for significantly longer.[40]

Although some of its stones were plundered for use elsewhere, the Pont du Gard remained largely intact. Its survival was due to its use as a toll bridge across the valley. In the 13th century the French king granted the seigneurs of Uzès the right to levy tolls on those using the bridge. The right later passed to the Bishops of Uzès. In return, they were responsible for maintaining the bridge in good repair.[39] However, it suffered serious damage during the 1620s when Henri, Duke of Rohan made use of the bridge to transport his artillery during the wars between the French royalists and the Huguenots, whom he led. To make space for his artillery to cross the bridge, the duke had one side of the second row of arches cut away to a depth of about one-third of their original thickness. This left a gap on the lowest deck wide enough to accommodate carts and cannons, but severely weakened the bridge in the process.[41]

In 1703 the local authorities renovated the Pont du Gard to repair cracks, fill in ruts and replace the stones lost in the previous century. A new bridge was built by the engineer Henri Pitot in 1743–47 next to the arches of the lower level, so that the road traffic could cross on a purpose-built bridge.[11][41] The novelist Alexandre Dumas was strongly critical of the construction of the new bridge, commenting that "it was reserved for the eighteenth century to dishonour a monument which the barbarians of the fifth had not dared to destroy."[42] The Pont du Gard continued to deteriorate and by the time Prosper Mérimée saw it in 1835 it was at serious risk of collapse from erosion and the loss of stonework.[43]

Napoleon III, who had a great admiration for all things Roman, visited the Pont du Gard in 1850 and took a close interest in it. He approved plans by the architect Charles Laisné to repair the bridge in a project which was carried out between 1855 and 1858, with funding provided by the Ministry of State. The work involved substantial renovations that included replacing the eroded stone, infilling some of the piers with concrete to aid stability and improving drainage by separating the bridge from the aqueduct. Stairs were installed at one end and the conduit walls were repaired, allowing visitors to walk along the conduit itself in reasonable safety.[43]

There have been a number of subsequent projects to consolidate the piers and arches of the Pont du Gard. It has survived three serious floods over the last century; in 1958 the whole of the lower tier was submerged by a giant flood that washed away other bridges,[43] and in 1998 another major flood affected the area. A further flood struck in 2002, badly damaging nearby installations.

The Pont du Gard was added to UNESCO's list of World Heritage Sites in 1985 on the criteria of "Human creative genius; testimony to cultural tradition; significance to human history".[44] The description on the list states: "The hydraulic engineers and ... architects who conceived this bridge created a technical as well as artistic masterpiece."[11]

Tourism

The Pont du Gard has been a tourist attraction for centuries. The outstanding quality of the bridge's masonry led to it becoming an obligatory stop for French journeyman masons on their traditional tour around the country (see Compagnons du Tour de France), many of whom have left their names on the stonework. From the 18th century onwards, particularly after the construction of the new road bridge, it became a famous staging-post for travellers on the Grand Tour and became increasingly renowned as an object of historical importance and French national pride.[45]

The bridge has had a long association with French monarchs seeking to associate themselves with a symbol of Roman imperial power. King Charles IX of France visited in 1564 during his Grand Tour of France and was greeted with a grand entertainment laid on by the Duc d'Uzès. Twelve young girls dressed as nymphs came out of a cave by the riverside near the aqueduct and presented the king with pastry and preserved fruits.[42] A century later, Louis XIV and his court visited the Pont du Gard during a visit to Nîmes in January 1660 shortly after the signature of the Treaty of the Pyrenees.[46] In 1786 his great-great-great-grandson Louis XVI commissioned the artist Hubert Robert to produce a set of paintings of Roman ruins of southern France to hang in the king's new dining room at the Palace of Fontainebleau, including a picture depicting the Pont du Gard in an idealised landscape. The commission was meant to reassert the ties between the French monarchy and the imperial past.[47] Napoleon III, in the mid-19th century, consciously identified with Augustus and accorded great respect to Roman antiquities; his patronage of the bridge's restoration in the 1850s was essential to its survival.[48]

By the 1990s the Pont du Gard had become a hugely popular tourist attraction but was congested with traffic – vehicles were still allowed to drive over the 1743 road bridge – and was cluttered with illegally built structures and tourist shops lining the river banks. As the architect Jean-Paul Viguier put it, the "appetite for gain" had transformed the Pont du Gard into "a fairground attraction".[49] In 1996 the General Council of the Gard département began a major four-year project to improve the area, sponsored by the French government, in conjunction with local sources, UNESCO and the EU. The entire area around the bridge was pedestrianised and a new visitor centre was built on the north bank to a design by Jean-Paul Viguier. The redevelopment has ensured that the area around the Pont du Gard is now much quieter due to the removal of vehicle traffic, and the new museum provides a much improved historical context for visitors.[50] The Pont du Gard is today one of France's top five tourist attractions, with 1.4 million visitors reported in 2001.[51]

Literary visitors

Since it became a tourist destination, many novelists and writers have visited the Pont du Gard and written of the experience. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was overwhelmed when he first visited it in 1738: [52]

I had been told to go and see the Pont du Gard; I did not fail to do so. It was the first work of the Romans that I had seen. I expected to see a monument worthy of the hands which had constructed it. This time the object surpassed my expectation, for the only time in my life. Only the Romans could have produced such an effect. The sight of this simple and noble work struck me all the more since it is in the middle of a wilderness where silence and solitude render the object more striking and the admiration more lively; for this so-called bridge was only an aqueduct. One asks oneself what force has transported these enormous stones so far from any quarry, and what brought together the arms of so many thousands of men in a place where none of them live. I wandered about the three storeys of this superb edifice although my respect for it almost kept me from daring to trample it underfoot. The echo of my footsteps under these immense vaults made me imagine that I heard the strong voices of those who had built them. I felt myself lost like an insect in that immensity. While making myself small, I felt an indefinable something that raised up my soul, and I said to myself with a sigh, "Why was I not born a Roman!"[53]

The novelist Henry James, visiting in 1884, was similarly impressed; he described the Pont du Gard as "unspeakably imposing, and nothing could well be more Roman." He commented:

The hugeness, the solidity, the unexpectedness, the monumental rectitude of the whole thing leave you nothing to say – at the time – and make you stand gazing. You simply feel that it is noble and perfect, that it has the quality of greatness ... When the vague twilight began to gather, the lonely valley seemed to fill itself with the shadow of the Roman name, as if the mighty empire were still as erect as the supports of the aqueduct; and it was open to a solitary tourist, sitting there sentimental, to believe that no people has ever been, or will ever be, as great as that, measured, as we measure the greatness of an individual, by the push they gave to what they undertook. The Pont du Gard is one of the three or four deepest impressions they have left; it speaks of them in a manner with which they might have been satisfied.[54]

The mid-19th-century writer Joseph Méry wrote in his 1853 book Les Nuits italiennes, contes nocturnes that on seeing the Pont du Gard:

[O]ne is struck dumb with astonishment; you are walking in a desert where nothing reminds you of man; cultivation has disappeared; there are ravines, heaths, blocks of rock, clusters of rushes, oaks, massed together, a stream which flows by a melancholy strand, wild mountains, a silence like that of Thebaid, and in the midst of this landscape springs up the most magnificent object that civilization has created for the glory of the fine arts.[55]

Hilaire Belloc wrote in 1928 that:

[W]hen one sees the thing all that is said of it comes true. Its isolation, its dignity, its weight, are all three awful. It looks as though it had been built long before all record by beings greater than ourselves, and were intended to stand long after the dissolution of our petty race. One can repose in it. I confess to a great reluctance to praise what has been praised too much; but so it is. A man, suffering from the unrest of our time, might do worse than camp out for three days, fishing and bathing under the shadow of the Pont du Gard.[56]

See also

References

- ↑ "EPCC du Pont du Gard". Culture-epcc.fr. 2008. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ Base Mérimée: PA00103291, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ↑ "Map of the Roman Aqueduct to Nîmes". Athena Review Image Archive. Athena Review. Archived from the original on 2017-11-15. Retrieved 2015-09-02.

- ↑ "Pont du Gard (Roman Aqueduct)". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ↑ Hodge, A. Trevor (2002). Roman aqueducts & water supply (2 ed.). London: Duckworth. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-7156-3171-3.

- ↑ Chanson, H. (1 October 2002). "Hydraulics of Large Culvert beneath Roman Aqueduct of Nîmes" (PDF). Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering. 128 (5): 326–330. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9437(2002)128:5(326). Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- 1 2 Bromwich, James (2006). Roman Remains of Southern France: A Guide Book. Routledge. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-415-14358-5.

- ↑ Lewis, Michael Jonathan Taunton (2001). Surveying instruments of Greece and Rome. Cambridge University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-521-79297-4.

- ↑ Hodge, p. 185

- ↑ Hodge, pp. 189–90

- 1 2 3 4 Langmead, Donald; Garnaut, Christine, eds. (2001). Encyclopedia of architectural and engineering feats. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 254. ISBN 1-57607-112-X.

- ↑ Sobin, Gustaf (1999). Luminous debris: reflecting on vestige in Provence and Languedoc. University of California Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-520-22245-8.

- ↑ Hodge, p. 285

- ↑ Hodge, p. 288

- ↑ Bromwich, p. 112

- ↑ Sobin, p. 217

- ↑ Bromwich, p. 111

- ↑ Bromwich, p. 112–113

- 1 2 "The Aqueduct at Pont du Gard". Athena Review. Athena Publications. 1 (4). Archived from the original on 2012-02-01. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- 1 2 Léger, Alfred (1875). "Acqueducs". Les travaux publics, les mines et la métallurgie aux temps des Romains, la tradition romaine jusqu'à nos jours (in French). Impr. J. Dejey & cie. pp. 551–676. OCLC 3263776. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ Deming, David (2010). Science and Technology in World History, Volume 1: The Ancient World and Classical Civilization. McFarland. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-7864-3932-4.

- 1 2 Michelin Green Guide Provence. Michelin Travel Publications. 2008. pp. 297–298. ISBN 978-1-906261-29-0.

- ↑ Fabre, Guilhem; Finches, Jean-Luc (1989). "L'aqueduc romain de Nîmes et le Pont du Gard". Pour la Science (40): 412–420.

- ↑ "Pont du Gard – An ancient work of art". Site du Pont du Gard. Retrieved 2012-07-12.

- ↑ Bessac, Jean-Claude; Vacca-Goutoulli, Mireille (1 January 2002). "La carrière romaine de L'Estel près du Pont du Gard" [The Roman Estel quarry next to the Pont du Gard] (PDF). Gallia (in French). 59 (1): 11–28. doi:10.3406/galia.2002.3093. S2CID 190982076. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ Bessac, Jean-Claude (1992). "Données et hypothèses sur les chantiers des carrières de l'Estel près du Pont du Gard" (PDF). Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise (in French). 25 (25): 397–430. doi:10.3406/ran.1992.1413. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ Gimpel, Jean (1993). The cathedral builders. Pimlico. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-06-091158-4.

- ↑ Paillet, Jean-Louis (1 January 2005). "Réflexions sur la construction du Pont du Gard" [Reflections on the construction of the Pont du Gard] (PDF). Gallia (in French). 62 (1): 49–68. doi:10.3406/galia.2005.3220. S2CID 191969914. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ↑ O'Connor, Colin (1993). Roman Bridges. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39326-4.

- ↑ Fabre, Guilhem (1992). The Pont du Gard : water and the Roman town. Paris: Caisse nationale des monuments historiques et des sites. ISBN 2-87682-079-X.

- 1 2 3 Bromwich, p. 119

- ↑ Espérandieu, Emile (1926). Le Pont du Gard et l'aqueduc de Nîmes (in French). Paris: H. Laurens. OCLC 616562598.

- 1 2 O'Rourke Boyle, Marjorie (1997). Divine domesticity: Augustine of Thagaste to Teresa of Avila. Leiden: Brill. p. 105. ISBN 9789004106758. Archived from the original on February 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Aqueduct Cherchell (Algeria)". Romanaqueducts.info. Retrieved 28 July 2012. (location:36°34′6.33″N 2°17′25.39″E / 36.5684250°N 2.2903861°E)

- ↑ Hill, Donald Routledge (1996). A history of engineering in classical and medieval times. Routledge. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-415-15291-4.

- ↑ Fabre, Guilhem; Fiches, Jean-Luc; Paillet, Jean-Louis (1991). "Interdisciplinary Research on the Aqueduct of Nimes and the Pont du Gard". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 4: 63–88. doi:10.1017/S104775940001549X. S2CID 193800472.

- ↑ Strachan, Edward; Bolton, Roy (2008). Russia & Europe in the Nineteenth Century. Sphinx Fine Art. p. 60. ISBN 9781907200021.

- ↑ Homer-Dixon, Thomas F. (2006). The upside of down: catastrophe, creativity, and the renewal of civilization. Island Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-59726-065-7.

- 1 2 Cleere, Henry (2001). Southern France: an Oxford archaeological guide. Oxford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-19-288006-2.

- ↑ Magnusson, Roberta J. (2001). Water Technology in the Middle Ages: Cities, Monasteries, and Waterworks after the Roman Empire. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0801866265.

- 1 2 Rennie, George (1855). "Description of the Pont du Gard". Minutes of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. 14: 238.

- 1 2 Wigan, Arthur C. (1856). The great wonders of the world: from the pyramids to the Crystal Palace. George Routledge and Sons. pp. 39–40.

- 1 2 3 Bromwich, p. 117

- ↑ UNESCO (2012). The World's Heritage. Collins. p. 229. ISBN 978-0007435616.

- ↑ Stirton, Paul (2003). Provence and the Côte d'Azur. A&C Black Publishers Ltd. p. 116. ISBN 0-393-30972-X.

- ↑ Laval, Eugène (1853). Monuments historiques du Gard. impr. de Soustelle-Gaude. p. XXI.

- ↑ McDonald, Christie; Hoffmann, Stacey (2010). Rousseau and Freedom. Cambridge University Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-521-51582-5.

- ↑ Hodge, p. 400 fn. 7

- ↑ Viguier, Jean-Paul (2009). Architecte. Odile Jacob. p. 11. ISBN 978-2-7381-2304-6.

- ↑ "Presentation works of Pont du Gard". Site du Pont du Gard. Archived from the original on 2012-08-30. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ Schmid, John (2001-08-22). "Euro Bill Hits a High Note With Folks in Small French Town". International Herald Tribune.

- ↑ Rousseau, Jean-Jacques (1889). . (in French). Launette. pp. 223–269 – via Wikisource.

- ↑ Rousseau, Jean-Jacques (1998). The Confessions and Correspondence, Including the Letters to Malesherbes. Vol. 5. trans. Christopher Kelly. UPNE. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-87451-836-8.

- ↑ James, Henry (1993). Howard, Richard (ed.). Collected Travel Writings: The Continent. A little tour in France ; Italian hours ; other travels. Library of America. pp. 189–90. ISBN 978-0-940450-77-6.

- ↑ Méry, Joseph (1858). "L'Italie des Gaules". Les nuits italiennes: contes nocturnes (in French). Paris: M. Lévy Frères. p. 280.

- ↑ Belloc, Hilaire (1928). Many cities. Constable.

External links

- Official Pont du Gard museum website

- Pont du Gard at Structurae

- Scale model of the Pont du Gard in Room IX of the Museo della Civiltà Romana in Rome.