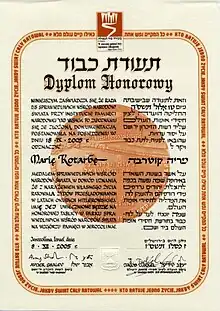

| Medals and diplomas awarded at a ceremony in the Polish Senate on 17 April 2012 | |

There are 7,177 Polish men and women recognized as Righteous by the State of Israel |

| Righteous Among the Nations |

|---|

|

| By country |

The citizens of Poland have the highest count of individuals who have been recognized by Yad Vashem as the Polish Righteous Among the Nations, for saving Jews from extermination during the Holocaust in World War II. There are 7,177 (as of 1 January 2021) Polish men and women conferred with the honor,[1] over a quarter of the 27,921 recognized by Yad Vashem in total.[2] The list of Righteous Among the Nations is not comprehensive and it is estimated that hundreds of thousands of Poles concealed and aided tens of thousands of their Polish-Jewish neighbors.[3] Many of these initiatives were carried out by individuals, but there also existed organized networks of Polish resistance which were dedicated to aiding Jews – most notably, the Żegota organization.

In German-occupied Poland, the task of rescuing Jews was difficult and dangerous. All household members were subject to capital punishment if a Jew was found concealed in their home or on their property.[4]

Activities

Before World War II, Poland's Jewish community had numbered about 3,460,000 – about 9.7 percent of the country's total population.[5] Following the invasion of Poland, Germany's Nazi regime sent millions of deportees from every European country to the concentration and forced-labor camps set up in the General Government territory of occupied Poland and across the Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany.[6] Most Jews were imprisoned in the Nazi ghettos, which they were forbidden to leave. Soon after the German–Soviet war had broken out in 1941, the Germans began their extermination of Polish Jews on either side of the Curzon Line, parallel to the ethnic cleansing of the Polish population including Romani and other minorities of Poland.[6]

As it became apparent that, not only were conditions in the ghettos terrible (hunger, diseases, executions), but that the Jews were being singled out for extermination at the Nazi death camps, they increasingly tried to escape from the ghettos and hide in order to survive the war.[7] Many Polish Gentiles concealed their Jewish neighbors. Many of these efforts arose spontaneously from individual initiatives, but there were also organized networks dedicated to aiding the Jews. Most notably, in September 1942 a Provisional Committee to Aid Jews (Tymczasowy Komitet Pomocy Żydom) was founded on the initiative of Polish novelist Zofia Kossak-Szczucka, of the famous artistic and literary Kossak family. This body soon became the Council for Aid to Jews (Rada Pomocy Żydom), known by the codename Żegota, with Julian Grobelny as its president and Irena Sendler as head of its children's section.[8][9]

It is not exactly known how many Jews were helped by Żegota, but at one point in 1943 it had 2,500 Jewish children under its care in Warsaw alone. At the end of the war, Sendler attempted to locate their parents but nearly all of them had been murdered at Treblinka. It is estimated that about half of the Jews who survived the war (thus over 50,000) were aided in some shape or form by Żegota.[10]

In numerous instances, Jews were saved by entire communities, with everyone engaged,[11] such as in the villages of Markowa[12] and Głuchów near Łańcut,[13] Główne, Ozorków, Borkowo near Sierpc, Dąbrowica near Ulanów, in Głupianka near Otwock,[14] Teresin near Chełm,[15] Rudka, Jedlanka, Makoszka, Tyśmienica, and Bójki in Parczew-Ostrów Lubelski area,[16] and Mętów, near Głusk. Numerous families who concealed their Jewish neighbours were killed for doing so.[12]

Risk

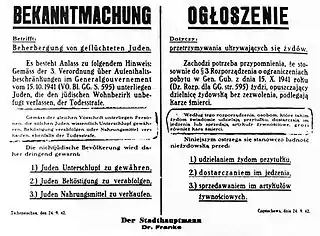

| Warning of death penalty for supporting Jews | |

|---|---|

NOTICE

Concerning: According to this decree, those knowingly helping these Jews by providing shelter, supplying food, or selling them foodstuffs are also subject to the death penalty. This is a categorical warning to the non-Jewish population against: Der Stadthauptmann Dr. Franke |

During the occupation of Poland (1939–1945), the Nazi German administration created hundreds of ghettos surrounded by walls and barbed-wire fences in most metropolitan cities and towns, with gentile Poles on the 'Aryan side' and the Polish Jews crammed into a fraction of the city space. On 15 October 1941, the death penalty was introduced by Hans Frank, governor of the General Government, to apply to Jews who attempted to leave the ghettos without proper authorization, and all those who "deliberately offer a hiding place to such Jews".[17] The law was made public by posters distributed in all major cities. The death penalty was also imposed for helping Jews in other Polish territories under the German occupation, but without issuing any legal act.[18]

Anyone from the Aryan side caught assisting those on the Jewish side in obtaining food was subject to the death penalty.[19][20] The usual punishment for aiding Jews was death, applied to entire families.[4][21][22] Polish rescuers were fully conscious of the dangers facing them and their families, not only from the invading Germans, but also from blackmailers (see: szmalcowniks) within the local, multi-ethnic population and the Volksdeutsche.[23] The Nazis implemented a law forbidding all non-Jews from buying from Jewish shops under the maximum penalty of death.[24]

Gunnar S. Paulsson, in his work on history of the Warsaw Jews during the Holocaust, has demonstrated that, despite the much harsher conditions, Warsaw's Polish residents managed to support and conceal the same percentage of Jews as did the residents of cities in safer countries of Western Europe, where no death penalty for saving them existed.[25]

Numbers

There are 7,177 officially recognized Polish Righteous – the highest count among nations of the world. At a 1979 international historical conference dedicated to Holocaust rescuers, J. Friedman said in reference to Poland: "If we knew the names of all the noble people who risked their lives to save the Jews, the area around Yad Vashem would be full of trees and would turn into a forest."[3] Hans G. Furth holds that the number of Poles who helped Jews is greatly underestimated and there might have been as many as 1,200,000 Polish rescuers.[3]

Father John T. Pawlikowski (a Servite priest from Chicago)[26] remarked that the hundreds of thousands of rescuers strike him as inflated.[27]

See also

- Stanisława Leszczyńska: a Polish midwife at the Auschwitz concentration camp

- History of the Jews in 20th-century Poland

- Holocaust in Poland

- "Polish death camp" controversy

Notes

- ↑ "Righteous Among the Nations Honored by Yad Vashem" (PDF).

- ↑ "Names of Righteous by Country | www.yadvashem.org". www.yadvashem.org. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 Furth, Hans G. (1999). "One million Polish rescuers of hunted Jews?". Journal of Genocide Research. 1 (2): 227–232. doi:10.1080/14623529908413952.

Thousands of helping acts were done on impulse, on the spur of the moment, lasting no longer than a few seconds to a few hours: such as a quick warning from mortal danger, giving some food or water, showing the way, sheltering from cold or exhaustion for a few hours. None of these acts can be recorded in full detail, with persons and names counted; yet without them the survival of thousands of Jews would not have been possible.[228] If these people are anywhere typical of non-Jews under the Nazis, the percentage of 20 percent [rescuers] represents a huge number of many millions. I was truly astonished when I read these numbers...[230]

- 1 2 “Righteous Among the Nations” by country at Jewish Virtual Library

- ↑ Węgrzynek, Hanna; Zalewska, Gabriela. "Demografia | Wirtualny Sztetl". sztetl.org.pl. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- 1 2 Franciszek Piper. "The Number of Victims" in Gutman, Yisrael & Berenbaum, Michael. Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp, Indiana University Press, 1994; this edition 1998, p. 62.

- ↑ Martin Gilbert. The Righteous: The Unsung Heroes of the Holocaust. Macmillan, 2003. pp 101.

- ↑ John T. Pawlikowski, Polish Catholics and the Jews during the Holocaust, in, Google Print, p. 113 in Joshua D. Zimmerman, Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath, Rutgers University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-8135-3158-6

- ↑ Andrzej Sławiński, Those who helped Polish Jews during WWII. Translated from Polish by Antoni Bohdanowicz. Article on the pages of the London Branch of the Polish Home Army Ex-Servicemen Association. Last accessed on 14 March 2008.

- ↑ Tadeusz Piotrowski (1997). "Assistance to Jews". Poland's Holocaust. McFarland & Company. p. 118. ISBN 0-7864-0371-3.

- ↑ Dariusz Libionka, "Polska ludność chrześcijańska wobec eksterminacji Żydów—dystrykt lubelski," in Dariusz Libionka, Akcja Reinhardt: Zagłada Żydów w Generalnym Gubernatorstwie Archived 4 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine (Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej–Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu, 2004), p.325. (in Polish)

- 1 2 The Righteous and their world. Markowa through the lens of Józef Ulma, by Mateusz Szpytma, Institute of National Remembrance

- ↑ Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, Wystawa „Sprawiedliwi wśród Narodów Świata”– 15 czerwca 2004 r., Rzeszów. "Polacy pomagali Żydom podczas wojny, choć groziła za to kara śmierci – o tym wie większość z nas." (Exhibition "Righteous among the Nations." Rzeszów, 15 June 2004. Subtitled: "The Poles were helping Jews during the war – most of us already know that.") Last actualization 8 November 2008. (in Polish)

- ↑ Jolanta Chodorska, ed., "Godni synowie naszej Ojczyzny: Świadectwa," Warsaw, Wydawnictwo Sióstr Loretanek, 2002, Part Two, pp.161–62. ISBN 83-7257-103-1 (in Polish)

- ↑ Kalmen Wawryk, To Sobibor and Back: An Eyewitness Account (Montreal: The Concordia University Chair in Canadian Jewish Studies, and The Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies, 1999), pp.66–68, 71.

- ↑ Bartoszewski and Lewinówna, Ten jest z ojczyzny mojej, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Znak, 1969, pp.533–34.

- ↑ Grądzka-Rejak & Namysło 2022, p. 103.

- ↑ Grądzka-Rejak & Namysło 2022, p. 103-104.

- ↑ Donald L. Niewyk, Francis R. Nicosia, The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust, Columbia University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-231-11200-9, Google Print, p.114

- ↑ Antony Polonsky, 'My Brother's Keeper?': Recent Polish Debates on the Holocaust, Routledge, 1990, ISBN 0-415-04232-1, Google Print, p.149

- ↑ Holocaust Survivors and Remembrance Project: Poland

- ↑ Robert D. Cherry, Annamaria Orla-Bukowska, Rethinking Poles and Jews: Troubled Past, Brighter Future, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007, ISBN 0-7425-4666-7, Google Print, p.5

- ↑ Mordecai Paldiel, The Path of the Righteous: Gentile Rescuers of Jews, page 184. Published by KTAV Publishing House Inc.

- ↑ Iwo Pogonowski, Jews in Poland, Hippocrene, 1998. ISBN 0-7818-0604-6. Page 99.

- ↑ Unveiling the Secret City Archived 12 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine H-Net Review: John Radzilowski

- ↑ Margaret Monahan Hogan, ed. (2011). "Remembering the Response of the Catholic Church" (PDF file, direct download 1.36 MB). History 1933 – 1948. What we choose to remember. University of Portland. pp. 85–97. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ↑ John T. Pawlikowski. Polish Catholics and the Jews during the Holocaust: Heroism, Timidity, and Collaboration. In: Joshua D. Zimmerman, Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath, Rutgers University Press, 2003.

Bibliography

- Grądzka-Rejak, Martyna; Namysło, Aleksandra (2022). "Prawodawstwo niemieckie wobec Polaków i Żydów na terenie Generalnego Gubernatorstwa oraz ziem wcielonych do III Rzeszy. Analiza porównawcza" [German legislation towards Poles and Jews in the General Government and the lands incorporated into the Third Reich. Comparative analysis]. In Domański, Tomasz (ed.). Stan badań nad pomocą Żydom na ziemiach polskich pod okupacją niemiecką (in Polish). Warsaw: Institute of National Remembrance. ISBN 9788382294194. OCLC 1325606240.

References

- Polish Righteous at the Museum of the History of Polish Jews

- Anna Poray, "Saving Jews: Polish Righteous. Those Who Risked Their Lives," at the Wayback Machine (archived 6 February 2008) with photographs and bibliography, 2004. List of Poles recognized as "Righteous among the Nations" by Israel's Yad Vashem (31 December 1999), with 5,400 awards including 704 of those who paid with their lives for saving Jews.

- Piotr Zychowicz, Do Izraela z bohaterami: Wystawa pod Tel Awiwem pokaże, jak Polacy ratowali Żydów Archived 10 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Rp.pl, 18 November 2009 (in Polish)