| Pithovirus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group I (dsDNA) |

| Order: | |

| Family: | Pithoviridae |

| Genus: | Pithovirus |

| Species | |

| |

Pithovirus, first described in a 2014 paper, is a genus of giant virus known from two species, Pithovirus sibericum, which infects amoebas[1][2] and Pithovirus massiliensis.[3] It is a double-stranded DNA virus and is a member of the nucleocytoplasmic large DNA viruses clade. The 2014 discovery was made when a viable specimen was found in a 30,000-year-old ice core harvested from permafrost in Siberia, Russia.

Description

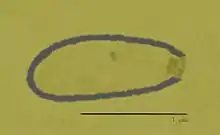

The genus name Pithovirus, a reference to large storage containers of ancient Greece known as pithoi, was chosen to describe the new species. A specimen of Pithovirus measures approximately 1.5 μm (1500 nm) in length and 0.5 μm (500 nm) in diameter, making it the largest virus yet found. It is 50% larger in size than the Pandoraviridae, the previous largest-known viruses,[4] and is larger than Ostreococcus, the smallest eukaryotic cell, although Pandoravirus has the largest viral genome, containing 1.9 to 2.5 megabases of DNA.[5]

Pithovirus has a thick, oval wall with an opening at one end. Internally, its structure resembles a honeycomb.[1]

The genome of Pithovirus contains 467 distinct genes, more than a typical virus, but far fewer than the 2556 putative protein-coding sequences found in Pandoravirus.[4] Thus, its genome is far less densely packed than any other known virus. Two-thirds of its proteins are unlike those of other viruses. Despite the physical similarity with Pandoravirus, the Pithovirus genome sequence reveals that it is barely related to that virus, but more closely resembles members of Marseilleviridae, Megaviridae, and Iridoviridae.[6] These families all contain large icosahedral viruses with DNA genomes. The Pithovirus genome has 36% GC-content, similar to the Megaviridae, in contrast to greater than 61% for pandoraviruses.[7]

Replication

Pithovirus' genome is one circular, double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) chromosome of about 610,000 base pairs (bp), encoding approximately 467 open reading frames (ORFs), which translate into 467 different proteins.[8] The genome encodes all the proteins needed to produce mRNA; these proteins are present in the purified virions.[6] Pithovirus therefore undergoes its entire replication cycle in its host's cytoplasm, rather than the more typical method of taking over the host's nucleus.[1][6][9]

Discovery

Pithovirus sibericum was discovered in a 30,000-year-old sample of Siberian permafrost by Chantal Abergel and Jean-Michel Claverie of Aix-Marseille University.[1][10] The virus was discovered buried 30 m (100 ft) below the surface of a late Pleistocene sediment.[2][6] It was found when riverbank samples collected in 2000 were exposed to amoebas.[11] The amoebas started dying and when examined were found to contain giant virus specimens. The authors said they got the idea to probe permafrost samples for new viruses after reading about an experiment that revived a similar aged seed of Silene stenophylla two years earlier.[1] The Pithovirus findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in March 2014.[4][7]

Although the virus is harmless to humans, its viability after being frozen for millennia has raised concerns that global climate change and tundra drilling operations could lead to previously undiscovered and potentially pathogenic viruses being unearthed.[4] However, other scientists dispute that this scenario poses a real threat.[1]

A modern species in the genus, Pithovirus massiliensis, was isolated in 2016. The core features such as the order of ORFs and orphan genes (ORFans) are well conserved between the two known species.[3]

Evolution

The rate of mutation of the genome has been estimated to be 2.23 × 10−6 substitutions/site/year.[12] The authors have suggested that these viruses evolved at least hundreds of thousands of years ago.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Yong, Ed (3 March 2014). "Giant virus resurrected from 69,000-year-old ice". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2014.14801. S2CID 87146458.

- 1 2 Morelle, Rebecca (3 March 2014). "30,000-year-old giant virus 'comes back to life'". BBC News.

- 1 2 Levasseur A, Andreani J, Delerce J, Bou Khalil J, Robert C, La Scola B, Raoult D (July 2016). "Comparison of a modern and fossil Pithovirus reveals its genetic conservation and evolution". Genome Biol Evol. 8 (8): 2333–9. doi:10.1093/gbe/evw153. PMC 5010891. PMID 27389688.

- 1 2 3 4 Sirucek, Stefan (3 March 2014). "Ancient "Giant Virus" Revived From Siberian Permafrost". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014.

- ↑ Brumfiel, Geoff (18 July 2013). "World's Biggest Virus May Have Ancient Roots". National Public Radio.

- 1 2 3 4 Racaniello, Vincent (4 March 2014). "Pithovirus: Bigger than Pandoravirus with a smaller genome". Virology Blog.

- 1 2 Legendre, M.; Bartoli, J.; Shmakova, L.; Jeudy, S.; Labadie, K.; Adrait, A.; Lescot, M.; Poirot, O.; Bertaux, L.; Bruley, C.; Coute, Y.; Rivkina, E.; Abergel, C.; Claverie, J.-M. (March 2014). "Thirty-thousand-year-old distant relative of giant icosahedral DNA viruses with a pandoravirus morphology". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 (11): 4274–9. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.4274L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1320670111. PMC 3964051. PMID 24591590.

- ↑ "Pithovirus sibericum". Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (SIB). Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ↑ Coghlan, Andy (3 March 2014). "Biggest-ever virus revived from Stone Age permafrost". NewScientist. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014.

- ↑ Pappas, Stephanie (16 September 2015). "Frozen Giant Virus Still Infectious After 30,000 Years". Yahoo News. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (3 March 2014). "Out of Siberian Ice, a Virus Revived". The New York Times.

- ↑ Duchêne, S; Holmes, EC (2018). "Estimating evolutionary rates in giant viruses using ancient genomes". Virus Evol. 4 (1): vey006. doi:10.1093/ve/vey006. PMC 5829572. PMID 29511572.

External links

- Viralzone: Pithovirus

- "Pithovirus sibericum". NCBI Taxonomy Browser. 1450746.