The Phrygian mode (pronounced /ˈfrɪdʒiən/) can refer to three different musical modes: the ancient Greek tonos or harmonia, sometimes called Phrygian, formed on a particular set of octave species or scales; the medieval Phrygian mode, and the modern conception of the Phrygian mode as a diatonic scale, based on the latter.

Ancient Greek Phrygian

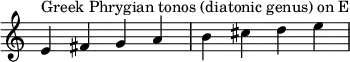

The octave species (scale) underlying the ancient-Greek Phrygian tonos (in its diatonic genus) corresponds to the medieval and modern Dorian mode. The terminology is based on the Elements by Aristoxenos (fl. c. 335 BCE), a disciple of Aristotle. The Phrygian tonos or harmonia is named after the ancient kingdom of Phrygia in Anatolia.

In Greek music theory, the harmonia given this name was based on a tonos, in turn based on a scale or octave species built from a tetrachord which, in its diatonic genus, consisted of a series of rising intervals of a whole tone, followed by a semitone, followed by a whole tone.

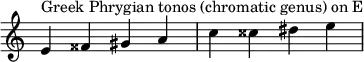

In the chromatic genus, this is a minor third followed by two semitones.

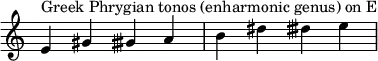

In the enharmonic genus, it is a major third and two quarter tones.

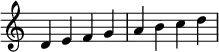

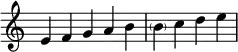

A diatonic-genus octave species built upon D is roughly equivalent to playing all the white notes on a piano keyboard from D to D:

This scale, combined with a set of characteristic melodic behaviours and associated ethoi, constituted the harmonia which was given the ethnic name "Phrygian", after the "unbounded, ecstatic peoples of the wild, mountainous regions of the Anatolian highlands".[1] This ethnic name was also confusingly applied by theorists such as Cleonides to one of thirteen chromatic transposition levels, regardless of the intervallic makeup of the scale.[2]

Since the Renaissance, music theorists have called this same sequence (on a diatonic scale) the "Dorian" mode, due to a mistake interpreting Greek (it is different from the Greek mode called "Dorian").

Medieval Phrygian mode

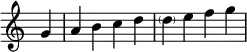

The early Catholic Church developed a system of eight musical modes that medieval music scholars gave names drawn from the ones used to describe the ancient Greek harmoniai. The name "Phrygian" was applied to the third of these eight church modes, the authentic mode on E, described as the diatonic octave extending from E to the E an octave higher and divided at B, therefore beginning with a semitone-tone-tone-tone pentachord, followed by a semitone-tone-tone tetrachord:[3]

The ambitus of this mode extended one tone lower, to D. The sixth degree, C, which is the tenor of the corresponding third psalm tone, was regarded by most theorists as the most important note after the final, though the fifteenth-century theorist Johannes Tinctoris implied that the fourth degree, A, could be so regarded instead.[3]

Placing the two tetrachords together, and the single tone at bottom of the scale produces the Hypophrygian mode (below Phrygian):

Modern Phrygian mode

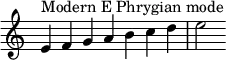

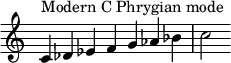

In modern western music (from the 18th century onward), the Phrygian mode is related to the modern natural minor scale, also known as the Aeolian mode, but with the second scale degree lowered by a semitone, making it a minor second above the tonic, rather than a major second.

The following is the Phrygian mode starting on E, or E Phrygian, with corresponding tonal scale degrees illustrating how the modern major mode and natural minor mode can be altered to produce the Phrygian mode:

E Phrygian Mode: E F G A B C D E Major: 1 ♭2 ♭3 4 5 ♭6 ♭7 1 Minor: 1 ♭2 3 4 5 6 7 1

Therefore, the Phrygian mode consists of: root, minor second, minor third, perfect fourth, perfect fifth, minor sixth, minor seventh, and octave. Alternatively, it can be written as the pattern

- half, whole, whole, whole, half, whole, whole

In contemporary jazz, the Phrygian mode is used over chords and sonorities built on the mode, such as the sus4(♭9) chord (see Suspended chord), which is sometimes called a Phrygian suspended chord. For example, a soloist might play an E Phrygian over an Esus4(♭9) chord (E–A–B–D–F).

Phrygian dominant scale

A Phrygian dominant scale is produced by raising the third scale degree of the mode:

E Phrygian dominant Mode: E F G♯ A B C D E Major: 1 ♭2 3 4 5 ♭6 ♭7 1 Minor: 1 ♭2 ♯3 4 5 6 7 1

The Phrygian dominant is also known as the Spanish gypsy scale, because it resembles the scales found in flamenco and also the Berber rhythms;[4] it is the fifth mode of the harmonic minor scale. Flamenco music uses the Phrygian scale together with a modified scale from the Arab maqām Ḥijāzī[5][6] (like the Phrygian dominant but with a major sixth scale degree), and a bimodal configuration using both major and minor second and third scale degrees.[6]

Examples

Ancient Greek

- The First Delphic Hymn, written in 128 BC by the Athenian composer Limenius, is in the Phrygian and Hyperphrygian tonoi, with much variation.[8]

- The Seikilos epitaph (1st century AD) is in the Phrygian species (diatonic genus), in the Iastian (or low Phrygian) transposition.[9]

Medieval and Renaissance

- Gregorian chant, Tristes erant apostoli, version in the Vesperale Romanum, originally Ambrosian chant.[10]

- The Roman chant variant of the Requiem introit "Rogamus te" is in the (authentic) Phrygian mode, or 3rd tone.[11]

- Orlando di Lasso's (d. 1594) motet In me transierunt.[12]

- Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina's (d. 1594) motet Congratulamini mihi.[13]

Baroque

- Johann Sebastian Bach keeps in his cantatas the Phrygian mode of some original chorale melodies, such as Luther's "Es woll uns Gott genädig sein" on a melody by Matthias Greitter, used twice in Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes, BWV 76 (1723) [14]

- Heinrich Schütz's Johannes-Passion (1666) is in the Phrygian mode[15]

- Dieterich Buxtehude's (d. 1707) Prelude in A minor, BuxWV 152,[16] (labeled Phrygisch in the BuxWV catalog)[17]

Romantic

- Johannes Brahms:

- Symphony No. 4, second movement. [18]

- Anton Bruckner:

- Ave Regina caelorum, WAB 8 (1885–88).[19]

- Pange lingua, WAB 33 (second setting, 1868).[20][21]

- Symphony no. 3, passages in the third (scherzo) and fourth movements .[22]

- Symphony no. 4 (third version, 1880), Finale.[23]

- Symphony no. 6, first, third (scherzo), and fourth movements.[24]

- Symphony no. 7, first movement.[25]

- Symphony no. 8, first and fourth movements.[26]

- Tota pulchra es, WAB 46 (1878).[27]

- Vexilla regis, WAB 51 (1892).[28]

- Isaac Albéniz' Rumores de la Caleta, Op. 71, No. 6

- Ralph Vaughan Williams' Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis,[29] based on Thomas Tallis's 1567 setting of Psalm 2, "Why fum'th in sight".

Contemporary classical music

- John Coolidge Adams, Phrygian Gates[30]

- Samuel Barber:

- Adagio for Strings, op. 11[31]

- "I Hear an Army", from Three Songs, op. 10[32]

- Philip Glass, the final aria from Satyagraha[33]

Film music

- Howard Shore, "Prologue" accompanying the opening sequence of the film, though the second half of the melody contains an A natural, which in the key of the piece makes it Phrygian Dominant. The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring.[34]

Jazz

- "Solea" by Gil Evans from Sketches of Spain (1960).[35]

- "Infant Eyes" by Wayne Shorter from Speak No Evil (1966)[36]

- "After the Rain" by John Coltrane from Impressions (1963)[36]

Rock

In practical terms it should be said that few rock songs that use modes such as the phrygian, Lydian, or locrian actually maintain a harmony rigorously fixed on them. What usually happens is that the scale is harmonized in [chords with perfect] fifths and the riffs are then played [over] those [chords].[37]

- "Symphony of Destruction" by Megadeth[38]

- "Forty Six & 2" by Tool (band)

- "Remember Tomorrow" by Iron Maiden[38][39]

- "Careful with That Axe, Eugene" and "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun" by Pink Floyd

- "Wherever I May Roam" by Metallica[39]

- "War" by Joe Satriani[38][39]

- "Sails of Charon" by Scorpions[38][39]

- "Unholy Confessions" by Avenged Sevenfold

- "Things We Said Today" by The Beatles

- "Magma" by King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard

Video games

- "Techno Syndrome" by Oliver Adams, from Mortal Kombat: The Album

See also

- Bhairavi, the equivalent scale (thaat) in Hindustani music

- Shoor, the main dastgah (scale) in Iranian music

- Hanumatodi, the equivalent scale (melakarta) in Carnatic music

- Neapolitan chord

- Phrygian cadence

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Solomon (1984), p. 249.

- ↑ Solomon (1984), pp. 244–246.

- 1 2 Sadie & Tyrrell 2001, "Phrygian" by Harold S. Powers.

- ↑ Thomas, Samuel. "Correlates between Berber and Flamenco Rhythms". Academia.

- ↑ Vargas, Enrique. "Modal Improvisation And Melodic Construction In The Flamenco Environment". Guitarras De Luthier.

- 1 2 Sadie & Tyrrell 2001, "Flamenco [cante flamenco]" by Israel J. Katz.

- ↑ Benward, Bruce, and Marilyn Nadine Saker. 2009. Music in Theory and Practice: Volume II, eighth edition. Boston: McGraw-Hill. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-07-310188-0.

- ↑ Pöhlmann, Egert, and Martin L. West. 2001. Documents of Ancient Greek Music: The Extant Melodies and Fragments, edited and transcribed with commentary by Egert Pöhlmann and Martin L. West. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 73. ISBN 0-19-815223-X.

- ↑ Solomon 1986, pp. 459, 461n14, 470.

- ↑ Otten, Joseph (1907). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2.

- ↑ Sadie & Tyrrell 2001, "Requiem Mass" (§1) by Theodore Karp, Fabrice Fitch and Basil Smallman.

- ↑ Pesic 2005, passim.

- ↑ Carver 2005, p. 77.

- ↑ Braatz, Thomas, and Aryeh Oron. April 2006. "Chorale Melodies used in Bach's Vocal Works Es woll (or wolle/wollt) uns Gott genädig sein". (accessed 24 October 2009)

- ↑ Sadie & Tyrrell 2001, "Schütz, Heinrich [Henrich] [Sagittarius, Henricus]" (§10) by Joshua Rifkin, Eva Linfield, Derek McCulloch and Stephen Baron.

- ↑ Sadie & Tyrrell 2001, "Buxtehude, Dieterich" by Kerala J. Snyder.

- ↑ Karstädt, G. (ed.). 1985. Thematisch-systematisches Verzeichnis der musikalischen Werke von Dietrich Buxtehude: Buxtehude-Werke-Verzeichnis, second edition. Wiesbaden. French online adaptation, "Dietrich Buxtehude, (c.1637–1707) Catalogue des oeuvres BuxWV: Oeuvres instrumentales: Musique pour orgue, BuxWV 136–225". Université du Québec website (Accessed 17 May 2011).

- ↑ Steinberg, Michael (1995). The Symphony: A Listener's Guide. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-19-512665-5.

- ↑ Carver 2005, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Carver 2005, p. 79.

- ↑ Partsch 2007, p. 227.

- ↑ Carver 2005, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Carver 2005, pp. 90–92.

- ↑ Carver 2005, pp. 91–98.

- ↑ Carver 2005, pp. 96–97.

- ↑ Carver 2005, p. 98.

- ↑ Carver 2005, pp. 79, 81–88.

- ↑ Carver 2005, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Sadie & Tyrrell 2001, "Vaughan Williams, Ralph" by Hugh Ottaway and Alain Frogley.

- ↑ Adams, John. 2010. "Phrygian Gates and China Gates". John Adams official web site. Accessed 7 August 2019.

- ↑ Pollack 2000, p. 191.

- ↑ Pollack 2000, p. 192.

- ↑ Sadie & Tyrrell 2001, "Glass, Philip" by Edward Strickland.

- ↑ Adams, Doug. 2010. The Music of the Lord of the Rings Films: A Comprehensive Account of Howard Shore's Scores. Van Nuys, California: Carpentier/Alfred Music Publishing. p. 54. ISBN 0-7390-7157-2.

- ↑ Pelletier-Bacquaert, Bruno. n.d. "Various Thoughts: Sus Chords", accessed December 10, 2009.

- 1 2 Baerman, Noah (1996). Complete Jazz Keyboard Method: Intermediate Jazz Keyboard, 21. Alfred Music. ISBN 9781457412905.

- ↑ Rooksby, Rikky (2010). Riffs: How to Create and Play Great Guitar Riffs. Backbeat. ISBN 9781476855486.

- 1 2 3 4 Serna, Desi (2008). Fretboard Theory, v. 1, p. 113. Guitar-Music-Theory.com. ISBN 9780615226224.

- 1 2 3 4 Serna, Desi (2021). Guitar Theory For Dummies with Online Practice, p.266. Wiley. ISBN 9781119842972.

Sources

- Carver, Anthony F. (February 2005). "Bruckner and the Phrygian Mode". Music & Letters. 86 (1): 74–99. doi:10.1093/ml/gci004.

- Partsch, Erich Wolfgang (2007). "Anton Bruckners phrygisches Pange lingua (WAB 33)". Singende Kirche. 54 (4): 227–229. ISSN 0037-5721.

- Pesic, Peter (2005). "Earthly Music and Cosmic Harmony: Johannes Kepler's Interest in Practical Music, Especially Orlando di Lasso". Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music. 11 (1).

- Pollack, Howard (Summer 2000). "Samuel Barber, Jean Sibelius, and the Making of an American Romantic". The Musical Quarterly. 84 (2): 175–205. doi:10.1093/musqtl/84.2.175.

- Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 9780195170672.

- Solomon, Jon (Summer 1984). "Towards a History of Tonoi". The Journal of Musicology. 3 (3): 242–251. doi:10.2307/763814. JSTOR 763814.

- Solomon, Jon (Winter 1986). "The Seikilos Inscription: A Theoretical Analysis". American Journal of Philology. 107 (4): 455–479. doi:10.2307/295097. JSTOR 295097.

Further reading

- Franklin, Don O. 1996. "Vom alten zum neuen Adam: Phrygischer Kirchenton und moderne Tonalität in J. S. Bachs Kantate 38". In Von Luther zu Bach: Bericht über die Tagung 22.–25. September 1996 in Eisenach, edited by Renate Steiger, 129–144. Internationalen Arbeitsgemeinschaft für theologische Bachforschung (1996): Eisenach. Sinzig: Studio-Verlag. ISBN 3-89564-056-5.

- Gombosi, Otto. 1951. "Key, Mode, Species". Journal of the American Musicological Society 4, no. 1:20–26. JSTOR 830117 (Subscription access) doi:10.1525/jams.1951.4.1.03a00020

- Hewitt, Michael. 2013. Musical Scales of the World. [s.l.]: The Note Tree. ISBN 978-0-9575470-0-1.

- Novack, Saul. 1977. "The Significance of the Phrygian Mode in the History of Tonality". Miscellanea Musicologica 9:82–177. ISSN 0076-9355 OCLC 1758333

- Tilton, Mary C. 1989. "The Influence of Psalm Tone and Mode on the Structure of the Phrygian Toccatas of Claudio Merulo". Theoria 4:106–122. ISSN 0040-5817