The PCE price index (PePP), also referred to as the PCE deflator, PCE price deflator, or the Implicit Price Deflator for Personal Consumption Expenditures (IPD for PCE) by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) and as the Chain-type Price Index for Personal Consumption Expenditures (CTPIPCE) by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), is a United States-wide indicator of the average increase in prices for all domestic personal consumption. It is benchmarked to a base of 2012 = 100. Using a variety of data including U.S. Consumer Price Index and Producer Price Index prices, it is derived from the largest component of the GDP in the BEA's National Income and Product Accounts, personal consumption expenditures.

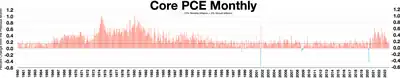

The personal consumption expenditure (PCE) measure is the component statistic for consumption in gross domestic product (GDP) collected by the United States Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). It consists of the actual and imputed expenditures of households and includes data pertaining to durable and non-durable goods and services. It is essentially a measure of goods and services targeted towards individuals and consumed by individuals.[1] The less volatile measure of the PCE price index is the core PCE (CPCE) price index, which excludes the more volatile and seasonal food and energy prices.

In comparison to the headline United States Consumer Price Index (CPI), which uses one set of expenditure weights for several years, this index uses a Fisher Price Index, which uses expenditure data from the current period and the preceding period. Also, the PCEPI uses a chained index which compares one quarter's price to the previous quarter's instead of choosing a fixed base. This price index method assumes that the consumer has made allowances for changes in relative prices. That is to say, they have substituted from goods whose prices are rising to goods whose prices are stable or falling.

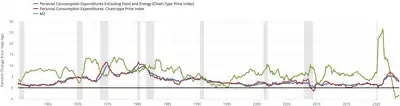

PCE has been tracked since January 1959. Through July 2018, inflation measured by PCE has averaged 3.3%, while it has averaged 3.8% using CPI.[2] This may be due to the failure of CPI to take into account the substitution effect. Alternatively, an unpublished report on this difference by the Bureau of Labor Statistics suggests that most of it is from different ways of calculating hospital expenses and airfares.[3]

Federal Reserve

In its "Monetary Policy Report to the Congress" ("Humphrey–Hawkins Report") from February 17, 2000 the FOMC said it was changing its primary measure of inflation from the consumer price index to the "chain-type price index for personal consumption expenditures".[4]

Comparison to CPI

The differences between the two indexes can be grouped into four categories: formula effect, weight effect, scope effect, and "other effects".

- The formula effect accounts for the different formulas used to calculate the two indexes. The PCE price index is based on the Fisher-Ideal formula, while the CPI is based on a modified Laspeyres formula.

- The weight effect accounts for the relative importance of the underlying commodities reflected in the construction of the two indexes.

- The scope effect accounts for conceptual differences between the two indexes. PCE measures spending by and on behalf of the personal sector, which includes both households and nonprofit institutions serving households; the CPI measures out-of-pocket spending by households. The "net" scope effect adjusts for CPI items out-of-scope of the PCE price index less items in the PCE price index that are out-of-scope of the CPI.

- "Other effects" include seasonal adjustment differences, price differences, and residual differences.[6]

- See more at: https://www.bea.gov/help/faq/555

| Consumption category | CPI-U | PCE-UNADJ | PCE-ADJ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food and beverages | 15.1% | 13.8% | 17.0% |

| Food at home | 8.0% | 7.1% | 8.7% |

| Food away from home | 6.0% | 4.9% | 6.0% |

| Alcoholic beverages | 1.1% | 1.8% | 2.3% |

| Housing | 42.4% | 26.5% | 32.9% |

| Rent | 5.8% | 3.4% | 4.1% |

| Owner's equivalent rent | 23.4% | 12.9% | 15.9% |

| Other housing | 13.1% | 10.2% | 12.9% |

| Apparel | 3.8% | 4.5% | 5.5% |

| Medical care | 6.2% | 22.3% | 5.0% |

| Transportation | 17.4% | 13.9% | 17.3% |

| Motor vehicles | 7.9% | 5.3% | 6.5% |

| Gasoline | 4.2% | 3.4% | 4.3% |

| Other transportation | 5.4% | 5.2% | 6.5% |

| Education and communication | 6.0% | 5.4% | 6.7% |

| Recreation | 5.6% | 6.8% | 8.4% |

| Tobacco | 0.7% | 1.0% | 1.2% |

| Other goods and services | 2.8% | 5.8% | 6.0% |

| 100% | 100% | 100% |

Source:[7]

The above chart is illustrative but may not reflect current values. The comparisons in the table above will vary over time as the relative weights of the components of the indexes change. The CPI base price and weightings are adjusted every two years.

The above table illustrates two commonly discussed important differences between the PCE deflator and CPI-U. The first is the relative importance of housing, which is due in part to the difference in scope mentioned above. CPI contains a large component of owner-equivalent rent, which by definition is an imputed value and not a real direct expenditure. The second major difference in weight is healthcare. This again stems from the definition of the index and the surveys used. CPI measures only the out-of-pocket healthcare costs of households where PCE includes healthcare purchased on behalf of households by third parties, including employer-provided health insurance. In the United States, employer health insurance is a large component and accounts for much of the difference in weights.

Another notable difference is that prices and weightings of the CPI are based on household surveys, while those of the PCE are based on business surveys. One reason for the difference in formulas is that not all the data needed for the Fisher-Ideal formula is available monthly even though it is considered superior. CPI is a practical alternative used to give a quicker read on prices in the previous month. PCE is typically revised three times in each of the months following the end of a quarter, and then the entire NIPA tables are re-based annually and every five years. Despite all these conceptual and methodological differences, the two indexes track fairly closely when averaged over several years.[8]

See also

- Price index

- GDP deflator (IPD for GDP)

- Household final consumption expenditure (HFCE)

- Inflation

References

- ↑ "Definition of 'Personal Consumption Expenditures - PCE'", Investopedia, Accessed 31-July-2012

- ↑ PCE and CPI indices, Jan 1959 - Jul 2018: "FRED Graph - FRED - St. Louis Fed". fred.stlouisfed.org. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- ↑ Boskin, et al. "Consumer Prices, The Consumer Price Index, and the Cost of Living." Journal of Economic Perspectives - Volume 12, Number 1. Winter 1998, pp3-26.

- ↑ "FRB: Monetary Policy Report to the Congress - February 17, 2000". www.federalreserve.gov. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- ↑ "What Does the Producer Price Index Tell You?". June 3, 2021.

- ↑ "What accounts for the differences in the PCE price index and the Consumer Price Index?". Archived from the original on July 27, 2018. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ↑ "Improving the Measurement of Consumer Expenditures" (PDF). nber.org. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ↑ Moyer, Brian C.; Stewart, Kenneth J. "A Reconciliation between the Consumer Price Index and the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index" (PDF). www.bea.gov. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Retrieved September 7, 2014.

External links

Data

- Briefing.com: Personal Income and Spending

- Briefing.com: CPI (the core CPI as a comparison)

- Current News Releases from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (click on "Personal Income and Outlays", then skip to Tables 9 and 11 near the bottom.)

- St. Louis Federal Reserve FRED2 PCE data index

Articles

- Personal Consumption Expenditures - PCE

- FAQ: What is the "market-based" PCE price index?

- Implicit Price Deflator for Personal Consumption Expenditures - Referendum 47's Measure of Inflation

- FRB: Monetary Policy Report to the Congress - February 17, 2000

- TheStreet.com: Meet the Fed's Elusive New Inflation Target