| Penis | |

|---|---|

Penis of an Asian elephant | |

| Details | |

| System | Reproductive system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | penis |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In many animals, a penis (/ˈpiːnɪs/; pl.: penises or penes) is the main male sexual organ used to inseminate females (or hermaphrodites) during copulation.[1][2] Such organs occur in both vertebrates and invertebrates, but males do not bear a penis in every animal species. Furthermore, penises are not necessarily homologous.

The term penis applies to many intromittent organs, but not to all. As an example, the intromittent organ of most Cephalopoda is the hectocotylus, a specialized arm, and male spiders use their pedipalps. Even within the Vertebrata, there are morphological variants with specific terminology, such as hemipenes.

In most species of animals in which there is an organ that might be described as a penis, it has no major function other than intromission, or at least conveying the sperm to the female, but in the placental mammals, the penis bears the distal part of the urethra, which discharges both urine during urination and semen during copulation.[3]

Vertebrates

The last common ancestor of all living amniotes (mammals, birds and reptiles) likely possessed a penis.[4]

Birds

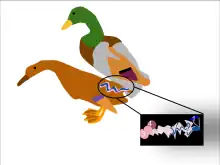

Most male birds (e.g., roosters and turkeys) have a cloaca (also present on the female), but not a penis. Among bird species with a penis are paleognathes (tinamous and ratites)[6] and Anatidae (ducks, geese and swans).[7] A bird penis is different in structure from mammal penises, being an erectile expansion of the cloacal wall and being erected by lymph, not blood.[8] It is usually partially feathered and in some species features spines and brush-like filaments, and in flaccid state curls up inside the cloaca.

While most male birds have no external genitalia, male waterfowl (Anatidae) have a phallus. Most birds mate with the males balancing on top of the females and touching cloacas in a "cloacal kiss"; this makes forceful insemination very difficult. The phallus that male waterfowl have evolved everts out of their bodies (in a clockwise coil) and aids in inseminating females without their cooperation.[9] The male waterfowl evolution of a phallus to forcefully copulate with females has led to counteradaptations in females in the form of vaginal structures called dead end sacs and clockwise coils. These structures make it harder for males to achieve intromission. The clockwise coils are significant because the male phallus everts out of their body in a counter-clockwise spiral; therefore, a clockwise vaginal structure would impede forceful copulation. Studies have shown that the longer a male's phallus is, the more elaborate the vaginal structures were.[9]

The lake duck is notable for possessing, in relation to body length, the longest penis of all vertebrates; the penis, which is typically coiled up in flaccid state, can reach about the same length as the animal himself when fully erect, but is more commonly about half the bird's length.[10][11] It is theorized that the remarkable size of their spiny penises with bristled tips may have evolved in response to competitive pressure in these highly promiscuous birds, removing sperm from previous matings in the manner of a bottle brush. The lake duck has a corkscrew shaped penis.[12]

Male and female emus are similar in appearance,[13] although the male's penis can become visible when he defecates.[14]

The male tinamou has a corkscrew shaped penis, similar to those of the ratites and to the hemipenis of some reptiles. Females have a small phallic organ in the cloaca which becomes larger during the breeding season.[15]

Mammals

As with any other bodily attribute, the length and girth of the penis can be highly variable between mammals of different species.[16][17] In many mammals, the size of a flaccid penis is smaller than its erect size.

A bone called the baculum is present in most mammals but absent in humans, cattle and horses.

In mammals, the penis is divided into three parts:[18]

- Roots (crura): these begin at the caudal border of the pelvic ischial arch.

- Body: the part of the penis extending from the roots.

- Glans: the free end of the penis.

The internal structures of the penis consist mainly of cavernous, erectile tissue, which is a collection of blood sinusoids separated by sheets of connective tissue (trabeculae). Some mammals have a lot of erectile tissue relative to connective tissue, for example horses. Because of this a horse's penis can enlarge more than a bull's penis. The urethra is on the ventral side of the body of the penis. As a general rule, a mammal's penis is proportional to its body size, but this varies greatly between species – even between closely related ones. For example, an adult gorilla's erect penis is about 4.5 cm (1.8 in) in length; an adult chimpanzee, significantly smaller (in body size) than a gorilla, has a penis size about double that of the gorilla. In comparison, the human penis is larger than that of any other primate, both in proportion to body size and in absolute terms.[19]

Artiodactyls

The penises of even-toed ungulates are curved in an S-shape when not erect.[20] In bulls, rams and boars, the sigmoid flexure of the penis straightens out during erection.[21]

When mating, the tip of a male pronghorn's penis is often the first part to touch the female pronghorn.[22] The pronghorn's penis is about 13 cm (5 in) long, and is shaped like an ice pick.[23] The front of a pronghorn's glans penis is relatively flat, while the back is relatively thick.[24] The male pronghorn usually ejaculates immediately after intromission.[25][26]

The penis of a dromedary camel is covered by a triangular penile sheath opening backwards,[27] and is about 60 cm (24 in) long.[28][29] The camelmen often aid the male to enter his penis into the female's vulva, though the male is considered able to do it on his own. Copulation time ranges from 7 to 35 minutes, averaging 11–15 minutes.[30][31]

Bulls have a fibro-elastic penis. Given the small amount of erectile tissue, there is little enlargement after erection. The penis is quite rigid when non-erect, and becomes even more rigid during erection. Protrusion is not affected much by erection, but more by relaxation of the retractor penis muscle and straightening of the sigmoid flexure.[32][18][33]

The male genitalia of mouse deer are similar to those of pigs.[34] A boar's penis, which rotates rhythmically during copulation,[35] is about 46 cm (18 in) long, and ejaculates about a pint of semen.[36] Wild boars have a roughly egg-sized sack near the opening of the penis, which collects urine and emits a sharp odour. The purpose of this is not fully understood.[37]

Deer

A stag's penis forms an S-shaped curve when it is not erect, and is retracted into its sheath by the retractor penis muscle.[38] Some deer species spray urine on their bodies by urinating from an erect penis.[39] One type of scent-marking behavior in elk is known as "thrash-urination,[40][41] which typically involves palpitation of the erect penis.[41][42][43] A male elk's urethra points upward so that urine is sprayed almost at a right angle to the penis.[41] A sambar stag will mark himself by spraying urine directly in the face with a highly mobile penis, which is often erect during its rutting activities.[44] Red deer stags often have erect penises during combat.[45]

Cetaceans

Cetaceans' reproductive organs are located inside the body. Male cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) have two slits, the genital groove concealing the penis and one further behind for the anus.[46][47][48][49] Cetaceans have fibroelastic penises, similar to those of Artiodactyla.[50] The tapering tip of the cetacean penis is called the pars intrapraeputialis or terminal cone.[51] The blue whale has the largest penis of any organism on the planet, typically measuring 2.4–3.0 m (8–10 ft).[52] Accurate measurements are difficult to take because its erect length can only be observed during mating,[53] which occurs underwater. The penis on a right whale can be up to 2.7 m (8.9 ft) – the testicles, at up to 2 m (6 ft 7 in) in length, 78 cm (2 ft 7 in) in diameter, and weighing up to 238 kg (525 lb), are also by far the largest of any animal on Earth.[54] On at least one occasion, a dolphin towed bathers through the water by hooking his erect penis around them.[55] Between captive male dolphins—including bottlenose dolphins and Amazon river dolphins—homosexual behaviour includes rubbing of genitals against each other, which sometimes leads to the males swimming belly to belly, inserting the penis in the other's genital slit and sometimes anus.[56][57]

Perissodactyls

Stallions (male horses) have a vascular penis. When non-erect, it is quite flaccid and contained within the prepuce (foreskin, or sheath).

Tapirs have exceptionally long penises relative to their body size.[58][59][60][61] The glans of the Malayan tapir resembles a mushroom, and is similar to the glans of the horse.[62] The penis of the Sumatran rhinoceros contains two lateral lobes and a structure called the processus glandis.[63]

Carnivores

_(20241179329).jpg.webp)

All members of Carnivora (except hyenas) have a baculum.[64] Canine penises have a structure at the base called the bulbus glandis.[65][66]

During copulation, the spotted hyena inserts his penis through the female's pseudo-penis instead of directly through the vagina, which is blocked by the false scrotum and testicles. Once the female retracts her clitoris, the male enters the female by sliding beneath her, an operation facilitated by the penis' upward angle.[67][68] The pseudo-penis closely resembles the male hyena's penis, but can be distinguished from the male's genitalia by its greater thickness and more rounded glans.[69] In male spotted hyenas, as well as females, the base of the glans is covered with penile spines.[70][71][72]

Domestic cats have barbed penises, with about 120–150 one millimeter long backwards-pointing spines.[73] Upon withdrawal of the penis, the spines rake the walls of the female's vagina, which is a trigger for ovulation. Lions also have barbed penises.[74][75] Male felids urinate backwards by curving the tip of the glans penis backward.[66][76] When male cheetahs urine-mark their territories, they stand one meter away from a tree or rock surface with the tail raised, pointing the penis either horizontally backward or 60° upward.[77]

The male fossa has an unusually long penis and baculum (penis bone), reaching to between his front legs when erect[78] with backwards-pointing spines along most of its length.[79] The male fossa has scent glands near the penis, with the penile glands emitting a strong odor.[78]

The beech marten's penis is larger than the pine marten's, with the bacula of young beech martens often outsizing those of old pine martens.[80]

Raccoons have penis bones which bend at a 90 degree angle at the tip.[81] The extrusibility of a raccoon's penis can be used to distinguish mature males from immature males.[82][83]

Male walruses possess the largest penis bones of any land mammal, both in absolute size and relative to body size.[84][85]

The adult male American mink's penis is 5.6 cm (2+1⁄4 in) long, and is covered by a sheath. The baculum is well-developed, being triangular in cross section and curved at the tip.[86]

Bats

Males of Racey's pipistrelle bat have a long, straight penis with a notch between the shaft and the narrow, egg-shaped glans penis. Near the top, the penis is haired, but the base is almost naked. In the baculum (penis bone), the shaft is long and narrow and slightly curved.[87] The length of the penis and baculum distinguish P. raceyi from all comparably sized African and Malagasy vespertilionids.[88] In males, penis length is 9.6 to 11.8 mm (3⁄8 to 15⁄32 in) and baculum length is 8.8 to 10.0 mm (11⁄32 to 13⁄32 in).[89]

Copulation by male greater short-nosed fruit bats is dorsoventral and the females lick the shaft or the base of the male's penis, but not the glans which has already penetrated the vagina. While the females do this, the penis is not withdrawn and research has shown a positive relationship between length of the time that the penis is licked and the duration of copulation. Post copulation genital grooming has also been observed.[90]

Rodents

The glans penis of the marsh rice rat is long and robust,[91] averaging 7.3 mm (9⁄32 in) long and 4.6 mm (3⁄16 in) broad, and the baculum (penis bone) is 6.6 mm (1⁄4 in) long.[92] As is characteristic of Sigmodontinae, the marsh rice rat has a complex penis, with the distal (far) end of the baculum ending in three digits.[93] The central digit is notably larger than those at the sides.[91] The outer surface of the penis is mostly covered by small spines, but there is a broad band of nonspinous tissue. The papilla (nipple-like projection) on the dorsal (upper) side of the penis is covered with small spines, a character the marsh rice rat shares only with Oligoryzomys and Oryzomys couesi among oryzomyines examined.[94] On the urethral process, located in the crater at the end of the penis,[95] a fleshy process (the subapical lobule) is present; it is absent in all other oryzomyines with studied penes except O. couesi and Holochilus brasiliensis.[96] The baculum is deeper than it is wide.[91]

In Transandinomys talamancae, the outer surface of the penis is mostly covered by small spines, but there is a broad band of nonspinous tissue.[97]

Some features of the accessory glands in the male genital region vary among oryzomyines. In Transandinomys talamancae,[98] a single pair of preputial glands is present at the penis. As is usual for sigmodontines, there are two pairs of ventral prostate glands and a single pair of anterior and dorsal prostate glands. Part of the end of the vesicular gland is irregularly folded, not smooth as in most oryzomyines.[99]

In Pseudoryzomys, the baculum (penis bone) displays large protuberances at the sides. In the cartilaginous part of the baculum, the central digit is smaller than those at the sides.[93]

In Drymoreomys, there are three digits at the tip of the penis, of which the central one is the largest.[100]

In Thomasomys ucucha, the glans penis is rounded, short, and small and is superficially divided into left and right halves by a trough at the top and a ridge at the bottom.[101]

The glans penis of a male cape ground squirrel is large with a prominent baculum.[102]

Unlike other squirrel species, red squirrels have long, thin, and narrow penises, without a prominent baculum.[103][104]

Winkelmann's mouse can easily be distinguished from its close relatives by the shape of its penis, which has a partially corrugated glans.[105]

The foreskin of a capybara is attached to the anus in an unusual way, forming an anogenital invagination.[106]

Primates

It has been postulated that the shape of the human penis may have been selected by sperm competition. The shape could have favored displacement of seminal fluids implanted within the female reproductive tract by rival males: the thrusting action which occurs during sexual intercourse can mechanically remove seminal fluid out of the cervix area from a previous mating.[107]

The penile morphology of some types of strepsirrhine primates has provided information about their taxonomy.[108] Male galago species possess very distinctive penile morphology that can be used to classify species.[109][110][111]

The northern greater galago penis is on average 18 mm (11⁄16 in) in length, with doubled headed or even tridentate spines pointing towards the body. They are less densely packed than in Otolemur crassicaudatus.[109][110][111] The penis of the ring-tailed lemur is nearly cylindrical in shape and is covered in small spines, as well as having two pairs of larger spines on both sides.[112]

The adult male of each vervet monkey species has a pale blue scrotum and a red penis,[113][114] and male proboscis monkeys have a red penis with a black scrotum.[115]

Male baboons and squirrel monkeys sometimes gesture with an erect penis as both a warning of impending danger and a threat to predators.[116][117] In male squirrel monkeys, this gesture is used for social communication.[118]

Humans

The human penis is an external sex organ of male humans. It is a reproductive, intromittent organ that additionally serves as the urinal duct. The main parts are the root of the penis (radix): It is the attached part, consisting of the bulb of penis in the middle and the crus of penis, one on either side of the bulb; the body of the penis (corpus); and the epithelium of the penis consists of the shaft skin, the foreskin, and the preputial mucosa on the inside of the foreskin and covering the glans penis.

The human penis is made up of three columns of tissue: two corpora cavernosa lie next to each other on the dorsal side and one corpus spongiosum lies between them on the ventral side. The urethra, which is the last part of the urinary tract, traverses the corpus spongiosum, and its opening, known as the meatus, lies on the tip of the glans penis. It is a passage both for urine and for the ejaculation of semen.

In males, the expulsion of urine from the body is done through the penis. The urethra drains the bladder through the prostate gland, where it is joined by the ejaculatory duct, and then onward to the penis.

An erection is the stiffening and rising of the penis, which occurs during sexual arousal, though it can also happen in non-sexual situations. Ejaculation is the ejecting of semen from the penis and is usually accompanied by orgasm. A series of muscular contractions delivers semen, containing male gametes known as sperm cells or spermatozoa, from the penis.

The most common form of genital alteration is circumcision, the removal of part or all of the foreskin for various cultural, religious, and more rarely medical reasons. There is controversy surrounding circumcision.

As of 2015, a systematic review of 15,521 men, who were measured by health professionals rather than themselves, concluded that the average length of an erect human penis is 13.12 cm (5.17 inches) long, while the average circumference of an erect human penis is 11.66 cm (4.59 inches).[119][120]

Marsupials

Most marsupials, except for the two largest species of kangaroos and marsupial moles[121] (assuming the latter are true marsupials), have a bifurcated penis, separated into two columns, so that the penis has two ends corresponding to the females' two vaginas.[122]

Monotremes

Monotremes and marsupial moles are the only mammals in which the penis is located inside the cloaca.[123][124]

Male echidnas have a bilaterally symmetrical, rosette-like, four-headed penis.[125] During mating, the heads on one side "shut down" and do not grow in size; the other two are used to release semen into the female's two-branched reproductive tract. The heads used are swapped each time the mammal copulates.[126][127][128] When not in use, the penis is retracted inside a preputial sac in the cloaca. The male echidna's penis is 7 cm (3 in) long when erect, and its shaft is covered with penile spines.[129] The penis is nearly a quarter of his body length when erect.[130]

Others

The penis of the bush hyrax is complex and distinct from that of the other hyrax genera. It has a short, thin appendage within a cup-like glans penis and measures greater than 6 cm (2+1⁄2 in) when erect. Additionally, it has been observed that the bush hyrax also has a greater distance between the anus and preputial opening in comparison to other hyraxes.[131]

An adult elephant has the largest penis of any land animal.[132] An elephant's penis can reach a length of 100 cm (40 in) and a diameter of 16 cm (6 in) at the base. It is S-shaped when fully erect and has a Y-shaped orifice.[133] During musth, a male elephant may urinate with his penis still in the sheath, which causes the urine to spray on the hind legs.[134][135] An elephant's penis is very mobile, being able to move independently of the male's pelvis,[136] and the penis curves forward and upward prior to mounting another elephant.[71]

In giant anteaters, the (retracted) penis and testicles are located internally between the rectum and urinary bladder.[137]

When the male armadillo Chaetophractus villosus is sexually aroused, species determination is easier. Its penis can be as long as 35 mm (1+1⁄2 in), and usually remains completely withdrawn inside a skin receptacle.[138] Scientists conducting studies on the C. villosus penis muscles revealed this species' very long penis exhibits variability. During its waking hours, it remains hidden beneath a skin receptacle, until it becomes erect and it projects outside in a rostral direction.[139]

Fish and reptiles

Male turtles and crocodiles have a penis, while male specimens of the reptile order Squamata have two paired organs called hemipenes. Tuataras must use their cloacae for reproduction.[140] Due to evolutionary convergence, turtle and mammal penises have a similar structure.[141]

In some fish, the gonopodium, andropodium, and claspers are intromittent organs (to introduce sperm into the female) developed from modified fins.

Invertebrates

Arthropods

The record for the largest penis size to body size ratio is held by the barnacle. The barnacle's penis can grow to up to forty times its own body length. This enables them to reach the nearest female for fertilization.

A number of invertebrate species have independently evolved the mating technique of traumatic insemination where the penis penetrates the female's abdomen, thereby creating a womb into which it deposits sperm. This has been most fully studied in bed bugs.

Some millipedes have penises. In these species, the penis is simply one or two projections on underneath the third body segment that produce a spermatophore or sperm packet. The act of insemination, however, occurs through specialized legs called gonopods which collect the spermatophore and insert it into the female.

Insects

In male insects, the structure analogous to a penis is known as aedeagus. The male copulatory organ of various lower invertebrate animals is often called the cirrus.[142]

The lesser water boatman's mating call, generated by rubbing the penis against the abdomen, is the loudest sound, relative to body size, in the animal kingdom.

In 2010, entomologist Charles Linehard described Neotrogla, a new genus of barkflies. Species of this genus have sex-reversed genitalia. Females have penis-like organs called gynosomes that are inserted into vagina-like openings of males during mating.[143] In 2014, a detailed study of the insects reproductive habits led by Kazunori Yoshizawae confirmed that the organ functions similar to a penis – for example, it swells during sexual intercourse – and is used to extract sperm from the male.[144][145]

Mollusks

The penis in most male coleoid cephalopods is a long and muscular end of the gonoduct used to transfer spermatophores to a modified arm called a hectocotylus. That, in turn, is used to transfer the spermatophores to the female. In species where the hectocotylus is missing, the penis is long and able to extend beyond the mantle cavity and transfers the spermatophores directly to the female. Deepwater squid have the greatest known penis length relative to body size of all mobile animals, second in the entire animal kingdom only to certain sessile barnacles. Penis elongation in Onykia ingens may result in a penis that is as long as the mantle, head and arms combined.[146][147] Giant squid of the genus Architeuthis are unusual in that they possess both a large penis and modified arm tips, although it is uncertain whether the latter are used for spermatophore transfer.[146]

Etymology

The word "penis" is taken from the Latin word for "tail". Some derive that from Indo-European *pesnis, and the Greek word πέος = "penis" from Indo-European *pesos. Prior to the adoption of the Latin word in English, the penis was referred to as a "yard". The Oxford English Dictionary cites an example of the word yard used in this sense from 1379,[148] and notes that in his Physical Dictionary of 1684, Steven Blankaart defined the word penis as "the Yard, made up of two nervous Bodies, the Channel, Nut, Skin, and Fore-skin, etc."[149] According to Wiktionary, this term meant (among other senses) "rod" or "bar".

As with nearly any aspect of the body involved in sexual or excretory functions, the penis is the subject of many slang words and euphemisms for it, a particularly common and enduring one being "cock". See WikiSaurus:penis for a list of alternative words for penis.

The Latin word "phallus" (from Greek φαλλος) is sometimes used to describe the penis, although "phallus" originally was used to describe representations, pictorial or carved, of the penis.[150]

Heraldry

Pizzles are represented in heraldry, where the adjective pizzled (or vilené[151]) indicates that part of an animate charge's anatomy, especially if coloured differently.

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Janet Leonard; Alex Cordoba-Aguilar R (18 June 2010). The Evolution of Primary Sexual Characters in Animals. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-971703-3. Archived from the original on 11 October 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ Schmitt, V.; Anthes, N.; Michiels, N. K. (2007). "Mating behaviour in the sea slug Elysia timida (Opisthobranchia, Sacoglossa): hypodermic injection, sperm transfer and balanced reciprocity". Frontiers in Zoology. 4: 17. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-4-17. PMC 1934903. PMID 17610714.

- ↑ Marvalee H. Wake (15 September 1992). Hyman's Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy. University of Chicago Press. p. 583. ISBN 978-0-226-87013-7. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Sanger TJ, Gredler ML, Cohn MJ (October 2015). "Resurrecting embryos of the tuatara, Sphenodon punctatus, to resolve vertebrate phallus evolution". Biology Letters. 11 (10): 20150694. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0694. PMC 4650183. PMID 26510679.

- ↑ Brennan, Patricia L. R.; Clark, Christopher J.; Prum, Richard O. (2010-05-07). "Explosive eversion and functional morphology of the duck penis supports sexual conflict in waterfowl genitalia". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 277 (1686): 1309–1314. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.2139. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 2871948. PMID 20031991.

- ↑ Julian Lombardi (1998). Comparative Vertebrate Reproduction. Springer. ISBN 978-0-7923-8336-9. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ↑ MobileReference (15 December 2009). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of European Birds: An Essential Guide to Birds of Europe. MobileReference. ISBN 978-1-60501-557-6. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ↑ Frank B. Gill (6 October 2006). Ornithology. Macmillan. pp. 414–. ISBN 978-0-7167-4983-7. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- 1 2 Brennan, P. L. R. et al. Coevolution of male and female genital morphology in waterfowl. PLoS ONE 2, e418 (2007).

- ↑ McCracken, Kevin G. (2000). "The 20-cm Spiny Penis of the Argentine Lake Duck (Oxyura vittata)" (PDF). The Auk. 117 (3): 820–825. doi:10.2307/4089612. JSTOR 4089612. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-09-23.

- ↑ McCracken, Kevin G.; Wilson, Robert E.; McCracken, Pamela J.; Johnson, Kevin P. (2001). "Sexual selection: Are ducks impressed by drakes' display?" (PDF). Nature. 413 (6852): 128. Bibcode:2001Natur.413..128M. doi:10.1038/35093160. PMID 11557968. S2CID 4321156. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-01-23.

- ↑ "Duck genitals locked in arms race | COSMOS magazine". Archived from the original on July 25, 2008.

- ↑ Eastman, p. 23.

- ↑ Coddington and Cockburn, p. 366.

- ↑ Cabot, J.; Carboneras, C.; Folch, A.; de Juanca, E.; Llimona, F.; Matheu, E. (1992). "Tinamiformes". In del Hoyo, J. (ed.). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. I: Ostrich to Ducks. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions.

- ↑ Tim Birkhead (2000). Promiscuity: An Evolutionary History of Sperm Competition. Harvard University Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-674-00666-9. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Virginia Douglass Hayssen; Ari Van Tienhoven (1993). Asdell's Patterns of Mammalian Reproduction: A Compendium of Species-Specific Data. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-1753-5. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- 1 2 William O. Reece (2009-03-04). Functional Anatomy and Physiology of Domestic Animals. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780813814513. Archived from the original on 2018-03-20.

- ↑ Sue Taylor Parker; Karin Enstam Jaffe (2008). Darwin's Legacy: Scenarios in Human Evolution. AltaMira Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-7591-0316-0. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Uwe Gille (2008). urinary and sexual apparatus, urogenital Apparatus. In: F.-V. Salomon and others (eds.): Anatomy for veterinary medicine. pp. 368–403. ISBN 978-3-8304-1075-1.

- ↑ Sergi Bonet; Isabel Casas; William V Holt; Marc Yeste (1 February 2013). Boar Reproduction: Fundamentals and New Biotechnological Trends. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-642-35049-8. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016.

- ↑ John A. Byers (1997). American Pronghorn: Social Adaptations and the Ghosts of Predators Past. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-08699-6. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ John A. Byers (30 June 2009). Built for Speed: A Year in the Life of Pronghorn. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02913-2. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Bart W. O'Gara; James D. Yoakum (2004). Pronghorn: ecology and management. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-0-87081-757-1. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ John A. Byers (1997). American Pronghorn: Social Adaptations and the Ghosts of Predators Past. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-08699-6. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ↑ John A. Byers (30 June 2009). Built for Speed: A Year in the Life of Pronghorn. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02913-2. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ↑ R. Yagil (1985). The desert camel: comparative physiological adaptation. Karger. ISBN 978-3-8055-4065-0. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ↑ Kohler-Rollefson, I. U. (12 April 1991). "Camelus dromedarius" (PDF). Mammalian Species (375): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3504297. JSTOR 3504297. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Malie Marie Sophie Smuts; Abraham Johannes Bezuidenhout (1987). Anatomy of the dromedary. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-857188-9. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ↑ Mukasa-Mugerwa, E. (1981-01-01). The Camel (Camelus dromedarius): A Bibliographical Review. p. 20. Archived from the original on 2014-03-26. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- ↑ Nomadic Peoples. Commission on Nomadic Peoples. 1992. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ↑ Sarkar, A. (2003). Sexual Behaviour In Animals. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7141-746-9.

- ↑ Gillespie, James R.; Flanders, Frank (2009-01-28). Modern Livestock and Poultry Production - James R. Gillespie, Frank B. Flanders. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1428318083. Archived from the original on 2013-02-04. Retrieved 2012-12-02.

- ↑ Vidyadaran, M. K.; et al. (1999). "Male genital organs and accessory glands of the lesser mouse deer, Tragulus javanicus" (PDF). Journal of Mammalogy. 80 (1): 199–204. doi:10.2307/1383219. JSTOR 1383219.

- ↑ William G. Eberhard (1996). Female Control: Sexual Selection by Cryptic Female Choice. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01084-7. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Geoffrey Miller (21 December 2011). The Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of Human Nature. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-81374-9. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Heptner, V. G.; Nasimovich, A. A.; Bannikov, A. G.; Hoffman, R. S. (1988) Mammals of the Soviet Union, Volume I, Washington, D.C. : Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science Foundation, pp. 19-82

- ↑ Leonard Lee Rue III (2004). The Deer of North America: The Standard Reference on All North American Deer Species--Behavior, Habitat, Distribution, and More. LYONS Press. ISBN 9781592284658. Archived from the original on 2013-05-28. Retrieved 2013-05-05.

- ↑ Fritz R. Walther (1984). Communication and expression in hoofed mammals. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-31380-5. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ↑ Dale R. McCullough (1969). The tule elk: its history, behavior, and ecology. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-01921-8. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 Youngquist, Robert S; Threlfall, Walter R (2006-11-23). Current Therapy in Large Animal Theriogenology. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781437713404. Archived from the original on 2013-05-11.

- ↑ Jay Houston (2008-07-07). Ultimate Elk Hunting: Strategies, Techniques & Methods. Cool Springs Press. ISBN 9781616732813. Archived from the original on 2013-05-11. Retrieved 2013-02-10.

- ↑ Struhsaker, Thomas T (1967). Behavior of elk (Cervus canadensis) during the rut. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- ↑ Deer of the world: their evolution, behaviour, and ecology. Valerius Geist. Stackpole Books. 1998. Pg. 73-77.

- ↑ Sommer, Volker; Vasey, Paul L. (2006-07-27). Homosexual Behaviour in Animals: An Evolutionary Perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 166–. ISBN 9780521864466. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ William F. Perrin; Bernd Wursig; J. G.M. Thewissen (26 February 2009). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-091993-5. Archived from the original on 11 October 2013. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ↑ Spencer Wilkie Tinker (1 January 1988). Whales of the World. Brill Archive. ISBN 978-0-935848-47-2.

- ↑ Würsig, Bernd; Wursig, Melany (2009-07-17). The Dusky Dolphin: Master Acrobat Off Different Shores - Bernd G. Würsig, Bernd Wursig, Melany Wursig. ISBN 9780080920351. Archived from the original on 2013-10-11. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

- ↑ Gibbons, Edward F.; Durrant, Barbara Susan; Demarest, Jack (1995). Conservation Endangered Spe: An Interdisciplinary Approach - Edward F. Gibbons, Jr., Barbara Susan Durrant, Jack Demarest. ISBN 9780791419113. Archived from the original on 2013-02-04. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

- ↑ Debra Lee Miller (19 April 2016). Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny of Cetacea: Whales, Porpoises and Dolphins. CRC Press. pp. 133–. ISBN 978-1-4398-4257-7. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018.

- ↑ American Institute of Biological Sciences (1977). Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises. University of California Press. GGKEY:T3BKXB87GHT. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ↑ "Reproduction". University of Wisconsin. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ "The Largest Penis in the World – Both for humans and animals, size does matter! – Softpedia". News.softpedia.com. 2007-01-05. Archived from the original on 2011-05-15. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- ↑ Feldhamer, George A.; Thompson, Bruce C.; Chapman, Joseph A. (2003). Wild mammals of North America : biology, management, and conservation (2nd ed.). Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 432. ISBN 9780801874161. Archived from the original on 2013-11-04. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- ↑ Unwin, Brian (2008-01-22). "'Tougher laws' to protect friendly dolphins". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2012-12-27.

- ↑ Serres, Agathe; Hao, Yujiang; Wang, Ding (November 11, 2021). "Socio-sexual interactions in captive finless porpoises and bottlenose dolphins". Marine Mammal Science. 38 (2). doi:10.1111/mms.12887.

- ↑ da Silva, Vera M. F.; Spinelli, Lucas G. (2023). "Play, Sexual Display, or Just Boredom Relief?". In Würsig, Bernd; Orbach, Dara N. (eds.). Sex in Cetaceans: Morphology, Behavior, and the Evolution of Sexual Strategies. Springer. pp. 153–171. ISBN 9783031356506.

- ↑ Endangered Wildlife and Plants of the World. Marshall Cavendish. 1 January 2001. pp. 1460–. ISBN 978-0-7614-7194-3. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ↑ M. R. N. Prasad (1974). Männliche Geschlechtsorgane. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-3-11-004974-9. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ↑ Daniel W. Gade (1999). Nature & Culture in the Andes. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 125–. ISBN 978-0-299-16124-8. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ Jeffrey Quilter (1 April 2004). Cobble Circles and Standing Stones: Archaeology at the Rivas Site, Costa Rica. University of Iowa Press. pp. 181–. ISBN 978-1-58729-484-6. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ Lilia, K.; Rosnina, Y.; Abd Wahid, H.; Zahari, Z. Z.; Abraham, M. (2010). "Gross Anatomy and Ultrasonographic Images of the Reproductive System of the Malayan Tapir (Tapirus indicus)" (PDF). Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia. 39 (6): 569–575. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0264.2010.01030.x. PMID 20809915. S2CID 46441225.

- ↑ Zainal Zahari, Z., et al. "Gross anatomy and ultrasonographic images of the reproductive system of the sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis). Archived 2018-03-20 at the Wayback Machine" Anatomia, histologia, embryologia 31.6 (2002): 350-354.

- ↑ "Baculum length and copulatory behaviour in carnivores and pinnipeds (Grand Order Ferae)". Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-06-03.

- ↑ Susan Long (2006). Veterinary Genetics and Reproductive Physiology. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7506-8877-2. Archived from the original on 2014-03-26. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- 1 2 R. F. Ewer (1998). The Carnivores. Cornell University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-8014-8493-3. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Szykman, M.; Van Horn, R. C.; Engh, A.L. Boydston; Holekamp, K. E. (2007). "Courtship and mating in free-living spotted hyenas" (PDF). Behaviour. 144 (7): 815–846. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.630.5755. doi:10.1163/156853907781476418. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-11-30.

- ↑ Estes 1998, p. 293

- ↑ Glickman, SE; Cunha, GR; Drea, CM; Conley, AJ; Place, NJ (2006). "Mammalian sexual differentiation: lessons from the spotted hyena" (PDF). Trends Endocrinol Metab. 17 (9): 349–356. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2006.09.005. PMID 17010637. S2CID 18227659. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-02-22.

- ↑ R. F. Ewer (1973). The Carnivores. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8493-3. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- 1 2 R. D. Estes (1991). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals: Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, Primates. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08085-0. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Catherine Blackledge (2003). The Story of V: A Natural History of Female Sexuality. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-3455-8. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Aronson, L. R.; Cooper, M. L. (1967). "Penile spines of the domestic cat: their endocrine-behavior relations" (PDF). Anat. Rec. 157 (1): 71–8. doi:10.1002/ar.1091570111. PMID 6030760. S2CID 13070242. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-06-20.

- ↑ Cats of Africa. Struik. 2005. ISBN 978-1-77007-063-9. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Philip Caputo (1 June 2003). Ghosts of Tsavo: Stalking the Mystery Lions of East Africa. Adventure Press, National Geographic. ISBN 978-0-7922-4100-3. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Reena Mathur (2009). Animal Behaviour 3/e. Rastogi Publications. ISBN 978-81-7133-747-7. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ T. M. Caro (15 August 1994). Cheetahs of the Serengeti Plains: Group Living in an Asocial Species. University of Chicago Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-226-09433-5. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- 1 2 Köhncke, M.; Leonhardt, K. (1986). "Cryptoprocta ferox" (PDF). Mammalian Species (254): 1–5. doi:10.2307/3503919. JSTOR 3503919. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 June 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ↑ Macdonald, D.W., ed. (2009). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Mammals. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14069-8.

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 881

- ↑ Leon Fradley Whitney (1952). The Raccoon. Practical Science Publishing Company. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ↑ Samuel I. Zeveloff (2002). Raccoons: A Natural History. UBC Press. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-0-7748-0964-1. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ Julie Feinstein (January 2011). Field Guide to Urban Wildlife. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0585-1. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ↑ Fay, F.H. (1985). "Odobenus rosmarus". Mammalian Species (238): 1–7. doi:10.2307/3503810. JSTOR 3503810. Archived from the original on 2013-09-15.

- ↑ Born, E. W.; Gjertz, I.; Reeves, R. R. (1995). Population assessment of Atlantic Walrus (Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus L.). Oslo, Norway: Meddelelser. Norsk Polarinstitut. p. 100.

- ↑ Feldhamer, Thompson & Chapman 2003, pp. 663–664

- ↑ Bates et al. 2006, p. 304

- ↑ Bates et al. 2006, pp. 306–307.

- ↑ Bates et al. 2006, table 1

- ↑ Tan, Min; Gareth Jones; Guangjian Zhu; Jianping Ye; Tiyu Hong; Shanyi Zhou; Shuyi Zhang; Libiao Zhang (October 28, 2009). Hosken, David (ed.). "Fellatio by Fruit Bats Prolongs Copulation Time". PLOS ONE. 4 (10): e7595. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7595T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007595. PMC 2762080. PMID 19862320.

- 1 2 3 Hooper & Musser 1964, p. 13

- ↑ Hooper & Musser 1964, table 1.

- 1 2 Weksler 2006, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Hooper & Musser 1964, p. 13; Weksler 2006, p. 57.

- ↑ Hooper & Musser 1964, p. 7.

- ↑ Weksler 2006, p. 57.

- ↑ Weksler 2006, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Described by Voss & Linzey 1981. Noted in Weksler 2006, p. 58, footnote 10

- ↑ Weksler 2006, pp. 57–58; Voss & Linzey 1981, p. 13.

- ↑ Percequillo, Weksler & Costa 2011, p. 367.

- ↑ Voss 2003, p. 11.

- ↑ Skurski, D.; Waterman, J. (2005). "Xerus inauris". Mammalian Species. 781: 1–4. doi:10.1644/781.1.

- ↑ Kim Long (1995). Squirrels: A Wildlife Handbook. Big Earth Publishing. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-55566-152-6. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Charles A. Long (2008). The Wild Mammals of Wisconsin. Pensoft Publishers. p. 341. ISBN 978-954-642-313-9. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Bradley, R.D. & Schmidley, D.J. (1987). "The glans penes and bacula in Latin American taxa of the Peromyscus boylii group". Journal of Mammalogy. 68 (3): 595–615. doi:10.2307/1381595. JSTOR 1381595.

- ↑ José Roberto Moreira; Katia Maria P.M.B. Ferraz; Emilio A. Herrera (15 August 2012). Capybara: Biology, Use and Conservation of an Exceptional Neotropical Species. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4614-4000-0. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ Shackelford, T. K.; Goetz, A. T. (2007). "Adaptation to Sperm Competition in Humans". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 16: 47–50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00473.x. S2CID 6179167.

- ↑ Dixson, Alan F. (26 January 2012). Primate Sexuality: Comparative Studies of the Prosimians, Monkeys, Apes, and Humans. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-150342-9. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- 1 2 Anderson, MJ (1998). "Comparative Morphology and Speciation in Galagos". Folia Primatol. 69 (7): 325–331. doi:10.1159/000052721. S2CID 202649686.

- 1 2 Dixson, AF (1989). "Sexual Selection, Genital Morphology, and Copulatory Behavior in Male Galagos". International Journal of Primatology. 1. 10: 47–55. doi:10.1007/bf02735703. S2CID 1129069.

- 1 2 Anderson, MJ (2000). "Penile Morphology and Classification of Bush Babies (Family Galagoninae)". International Journal of Primatology. 5. 21 (5): 815–836. doi:10.1023/A:1005542609002. S2CID 9983759.

- ↑ Wilson, D.E.; Hanlon, E. (2010). "Lemur catta (Primates: Lemuridae)" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 42 (854): 58–74. doi:10.1644/854.1. S2CID 20361726. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-05-10.

- ↑ Fedigan L, Fedigan LM (1988). Cercopithecus aethiops: a review of field studies. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press. pp. 389–411.

- ↑ Apps, Peter (2000). Wild Ways: Field Guide to the Behaviour of Southern African Mammals. Struik. ISBN 978-1-86872-443-7. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Friderun Ankel-Simons (27 July 2010). Primate Anatomy: An Introduction. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-046911-9. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Nasaw, Daniel (February 6, 2012). "When did the middle finger become offensive?". BBC News Magazine. BBC. Archived from the original on February 6, 2012. Retrieved February 7, 2012.

- ↑ Oricchio, Michael (June 20, 1996). "Davis' Infamous Finger Salute Has Had a Big Hand in History; Folklorists: Roots Go Back At Least 2,000 Years To Ancient Rome". San Jose Mercury News. p. 16A. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2012. (subscription required)

- ↑ Blitz J.; Ploog D.W.; Ploog F. (1963). "Studies on the social and sexual behavior of the squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus)". Folia Primatologica. 1: 29–66. doi:10.1159/000164879.

- ↑ Berezow, Alex B. (March 2, 2015). "Is Your Penis Normal? There's a Chart for That". RealClearScience.com. RealClearScience. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- ↑ Veale, D.; Miles, S.; Bramley, S.; Muir, G.; Hodsoll, J. (2015). "Am I normal? A systematic review and construction of nomograms for flaccid and erect penis length and circumference in up to 15 521 men". BJU International. 115 (6): 978–986. doi:10.1111/bju.13010. PMID 25487360. S2CID 36836535.

- ↑ On the Habits and Affinities of the New Australian Mammal, Notoryctes typhlops E. D. Cope The American Naturalist Vol. 26, No. 302 (Feb., 1892), pp. 121-128

- ↑ Renfree, Marilyn; Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe (1987-01-30). Reproductive Physiology of Marsupials. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521337922. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ Gadow, H. On the systematic position of Notoryctes typhlops. Proc. Zool. Soc. London 1892, 361–370 (1892).

- ↑ Riedelsheimer, B., Unterberger, P., Künzle, H. and U. Welsch. 2007. Histological study of the cloacal region and associated structures in the hedgehog tenrec Echinops telfairi. Mammalian Biology 72(6): 330-341.

- ↑ Michael L. Augee; Brett A. Gooden; Anne Musser (January 2006). Echidna: Extraordinary Egg-laying Mammal. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-09204-4. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Shultz, N. (26 October 2007). "Exhibitionist spiny anteater reveals bizarre penis". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 27 October 2006.

- ↑ Augee, Gooden and Musser, p. 81.

- ↑ Johnston, S.D.; Smith, B.; Pyne, M.; Stenzel, D.; Holt, W.V. (2007). "One-Sided Ejaculation of Echidna Sperm Bundles (Tachyglossus aculeatus)" (PDF). Am. Nat. 170 (6): E162–4. doi:10.1086/522847. PMID 18171162. S2CID 40632746.

- ↑ Larry Vogelnest; Rupert Woods (18 August 2008). Medicine of Australian Mammals. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-09928-9. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Mammalogy. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 21 April 2011. pp. 389–. ISBN 978-0-7637-6299-5. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ Barry, R.E.; Shoshani, J. (2000). "Heterohyrax brucei". Mammalian Species. 645: 1–7. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2000)645<0001:hb>2.0.co;2. S2CID 28256848.

- ↑ Giustina, Anthony (31 December 2005). Sex World Records. Lulu.com. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-4116-6774-7. Archived from the original on 11 October 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ Shoshani, p. 80.

- ↑ Smithers, Reay H. N. (March 2008). Smithers' Mammals of Southern Africa: A Field Guide. Penguin Random House South Africa. ISBN 9781868725502. Archived from the original on 2013-10-11. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- ↑ Sukumar, pp. 100–08.

- ↑ Murray E. Fowler; Susan K. Mikota (2 October 2006). Biology, Medicine, and Surgery of Elephants. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 353–. ISBN 978-0-8138-0676-1. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ↑ Naugher, K. B. (2004). "Anteaters (Myrmecophagidae)". In Hutchins, M.; Kleiman, D. G; Geist, V.; McDade, M. С. (eds.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 13 (2nd ed.). Gale. pp. 171–79. ISBN 978-0-7876-7750-3.

- ↑ "New data on armadillos (Xenarthra: Dasypodidae) for Central Patagonia, Argentina." Agustin M. Abba, et al.

- ↑ Affanni, J. M.; Cervino, C. O.; Marcos, H. J. A. (2001). "Absence of penile erections during paradoxical sleep. Peculiar penile events during wakefulness and slow wave sleep in the armadillo". Journal of Sleep Research. 10 (3): 219–228. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2869.2001.00259.x. hdl:20.500.12110/paper_09621105_v10_n3_p219_Affanni. PMID 11696075. S2CID 22421482.

- ↑ Lutz, Dick (2005), Tuatara: A Living Fossil, Salem, Oregon: DIMI PRESS, ISBN 0-931625-43-2

- ↑ Kelly, D. A. (2004). "Turtle and mammal penis designs are anatomically convergent". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 271 (Suppl 5): S293–S295. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0161. PMC 1810052. PMID 15503998.

- ↑ "Penis | Description, Anatomy, & Physiology | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Lienhard, Charles; Oliveira do Carmo, Thais; Lopes Ferreira, Rodrigo (2010). "A new genus of Sensitibillini from Brazilian caves (Psocodea: 'Psocoptera': Prionoglarididae)". Revue Suisse de Zoologie. 117 (4): 611–635. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.117600. ISSN 0035-418X. Archived from the original on 2014-11-03.

- ↑ Kazunori Yoshizawae; Rodrigo L. Ferreira; Yoshitaka Kamimura; Charles Lienhard (17 April 2014). "Female Penis, Male Vagina, and Their Correlated Evolution in a Cave Insect". Current Biology. 24 (9): 1006–1010. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.022. hdl:2115/56857. PMID 24746797.

- ↑ Cell Press (17 April 2014). "In sex-reversed cave insects, females have the penises". Science Daily. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- 1 2 Arkhipkin, A.I.; Laptikhovsky, V.V. (2010). "Observation of penis elongation in Onykia ingens: implications for spermatophore transfer in deep-water squid". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 76 (3): 299–300. doi:10.1093/mollus/eyq019.

- ↑ Walker, M. 2010. Super squid sex organ discovered Archived 2010-07-07 at the Wayback Machine. BBC Earth News, July 7, 2010.

- ↑ Basu, S. C. (2011). Male Reproductive Dysfunction. JP Medical Ltd. p. 101. ISBN 9789350252208.

- ↑ Simpson, John, ed. (1989). "penis, n.". Oxford English Dictionary (second ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861186-8.

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- ↑ Rietstap, J. B. (1884). "Armorial général; précédé d'un Dictionnaire des termes du blason". G. B. van Goor zonen: XXXI.

Vilené: se dit un animal qui a la marque du sexe d'un autre émail que le corps

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

General and cited references

Horses

- Walker, Donald F.; Vaughan, John T. (1 June 1980). Bovine and equine urogenital surgery. Lea & Febiger. ISBN 978-0-8121-0284-0. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- "The Stallion: Breeding Soundness Examination & Reproductive Anatomy". University of Wisconsin-Madison. Archived from the original on 2007-07-16. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- Munroe, Graham; Weese, Scott (15 March 2011). Equine Clinical Medicine, Surgery and Reproduction. Manson Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84076-608-0. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- Budras, Klaus Dieter; Sack (1 March 2012). Anatomy of the Horse. Manson Publishing. ISBN 978-3-8426-8368-6. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- England, Gary (15 April 2008). Fertility and Obstetrics in the Horse. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-75041-4. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- Equine Research (2004). Horse Conformation: Structure, Soundness, and Performance. Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-59228-487-0. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- Evans, James Warren (15 February 1990). The Horse. W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-1811-6. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- Hayes, M. Horace; Rossdale, Peter D. (March 1988). Veterinary Notes for Horse Owners: An Illustrated Manual of Horse Medicine and Surgery. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-76561-3. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- McBane, Susan (2001). Modern Horse Breeding: A Guide for Owners. Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 978-1-58574-389-6. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

Marsupials

- Parker, Rick (13 January 2012). Equine Science (4 ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-111-13877-6. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- Flannery, Tim (2008). Chasing Kangaroos: A Continent, a Scientist, and a Search for the World's Most Extraordinary Creature. Grove/Atlantic, Incorporated. pp. 60–. ISBN 9780802143716. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- Hunsaker, Don II (2 December 2012). The Biology of Marsupials. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-323-14620-3. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- Jones, Menna E.; Dickman, Chris R.; Archer, Mike; Archer, Michael (2003). Predators With Pouches: The Biology of Carnivorous Marsupials. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 9780643066342. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- King, Anna (2001). "Discoveries about Marsupial Reproduction". Iowa State University Biology Dept. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

- Stonehouse, Bernard; Gilmore, Desmond (1977). The Biology of marsupials. University Park Press. ISBN 978-0-8391-0852-8. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- Tyndale-Biscoe, C. Hugh (2005). Life of Marsupials. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-06257-3. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

Other animals

- Austin, Colin Russell; Short, Roger Valentine (21 March 1985). Reproduction in Mammals: Volume 4, Reproductive Fitness. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31984-3. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Bassert, Joanna M.; McCurnin, Dennis M. (1 April 2013). McCurnin's Clinical Textbook for Veterinary Technicians. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1-4557-2884-8. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- Bates, Paul J. J.; Ratrimomanarivo, Fanja H.; Harrison, David L.; Goodman, Steven M. (December 2006). "A description of a new species of Pipistrellus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) from Madagascar with a review of related Vespertilioninae from the island". Acta Chiropterologica. 8 (2): 299–324. doi:10.3161/1733-5329(2006)8[299:ADOANS]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85825521.

- Beck, Benjamin B.; Wemmer, Christen M. (1983). The Biology and management of an extinct species: Père David's deer. Noyes Publications. ISBN 978-0-8155-0938-7. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- Burns, Eugene (1953). The sex life of wild animals: a North American study. Rinehart. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- Carnaby, Trevor (22 January 2007). Beat About the Bush: Mammals. Jacana Media. ISBN 978-1-77009-240-2. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Brehm, Alfred Edmund (1895). "Brehm's Life of Animals". Chicago: A. N. Marquis & Company. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Elbroch, Lawrence Mark; Kresky, Michael Raymond; Evans, Jonah Wy (7 April 2012). Field Guide to Animal Tracks and Scat of California. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-95164-8. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- Eltringham, Stewart Keith (1979). The ecology and conservation of large African mammals. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-23580-5. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- Estes, Richard (1998). The safari companion: a guide to watching African mammals, including hoofed mammals, carnivores, and primates. Chelsea Green Publishing. ISBN 978-1-890132-44-6.

- Frandson, Rowen D.; Wilke, W. Lee; Fails, Anna Dee (30 June 2009). Anatomy and Physiology of Farm Animals. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-8138-1394-3. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- Geist, Valerius (1993). Elk Country. T&N Children's Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55971-208-8. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- Hayssen, Virginia Douglass; Tienhoven, Ari Van (1993). Asdell's Patterns of Mammalian Reproduction: A Compendium of Species-Specific Data. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-1753-5. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskii, A. A. (2002). Mammals of the Soviet Union. Vol. II, part 1b, Carnivores (Mustelidae and Procyonidae). Washington, D.C. : Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science Foundation. ISBN 978-90-04-08876-4. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- Hoffmeister, Donald F. (2002). Mammals of Illinois. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07083-9. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Hooper, E.T.; Musser, G.G. (1964). "The glans penis in Neotropical cricetines (Family Muridae) with comments on classification of muroid rodents". Miscellaneous Publications of the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. 123: 1–57. hdl:2027.42/56367.

- Horowitz, Barbara N.; Bowers, Kathryn (12 June 2012). Zoobiquity: What Animals Can Teach Us About Being Human. Doubleday Canada. ISBN 978-0-385-67061-6. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- Horwich, Robert H. (June 1972). The ontogeny of social behavior in the gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis). P. Parey. ISBN 978-3-489-68036-9. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- Jackson, Hartley H. (January 1961). Mammals of Wisconsin. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-02150-4. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Journal of the Mammalogical Society of Japan. The Society. 1986. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- Khanna, Dev Raj; Yadav, P. R. (1 January 2005). Biology Of Mammals. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7141-934-0. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- Kingdon, Jonathan (January 1984). East African Mammals: An Atlas of Evolution in Africa. Vol. I. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-43718-7. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Kingdon, Jonathan (1984). East African Mammals: An Atlas of Evolution in Africa. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226437187.

- König, Horst Erich; Liebich, Hans-Georg (2007). Veterinary Anatomy of Domestic Mammals: Textbook and Atlas. Schattauer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7945-2485-3. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- Kotpal, R. L. (2010). Modern Text Book Of Zoology Vertebrates. Rastogi Publications. ISBN 978-81-7133-891-7. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- Krause, William J. (1 March 2008). An Atlas of Opossum Organogenesis. Universal-Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58112-969-4. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- Linzey, Donald W. (28 December 2011). Vertebrate Biology. JHU Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0040-2. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- Lukefahr, Steven D.; Cheeke, Peter R.; Patton, Nephi M. (2013). Rabbit Production. CABI. ISBN 978-1-78064-012-9. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- Natural History Bulletin of the Siam Society. 1975. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- Percequillo, A.R.; Weksler, M.; Costa, L.P. (2011). "A new genus and species of rodent from the Brazilian Atlantic Forest (Rodentia: Cricetidae: Sigmodontinae: Oryzomyini), with comments on oryzomyine biogeography". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 161 (2): 357–390. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2010.00643.x.

- Rose, Kenneth D.; Archibald, J. David (22 February 2005). The Rise of Placental Mammals: Origins and Relationships of the Major Extant Clades. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8022-3. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Roze, Uldis (2009). The North American Porcupine. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4646-7. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- Sarkar, Amita (1 January 2003). Sexual Behaviour In Animals. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7141-746-9. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- Schatten, Heide; Constantinescu, Gheorghe M. (21 March 2008). Comparative Reproductive Biology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-39025-2. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- Small, Meredith F. (1993). Female Choices: Sexual Behavior of Female Primates. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8305-9. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- Skinner, J. D.; Chimimba, Christian T. (15 November 2005). The Mammals of the Southern African Sub-region. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84418-5. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Staker, Lynda (2006). The Complete Guide to the Care of Macropods: A Comprehensive Guide to the Handrearing, Rehabilitation and Captive Management of Kangaroo Species. Lynda Staker. ISBN 978-0-9775751-0-7. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Strum, Shirley C.; Fedigan, Linda Marie (15 August 2000). Primate Encounters: Models of Science, Gender, and Society. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-77754-2. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Sturtz, Robin; Asprea, Lori (30 July 2012). Anatomy and Physiology for Veterinary Technicians and Nurses: A Clinical Approach. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-40585-7. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Peter J Chenoweth; Steven Lorton (30 April 2014). Animal Andrology: Theories and Applications. CABI. ISBN 978-1-78064-316-8.

- Verts, B. J.; Carraway, Leslie N. (1998). Land Mammals of Oregon. University of California Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-520-21199-5. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- Voss, R.S.; Linzey, A.V. (1981). "Comparative gross morphology of male accessory glands among Neotropical Muridae (Mammalia: Rodentia) with comments on systematic implications". Miscellaneous Publications of the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. 159: 1–41. hdl:2027.42/56403.

- Voss, R.S (2003). "A new species of Thomasomys (Rodentia: Muridae) from eastern Ecuador, with remarks on mammalian diversity and biogeography in the Cordillera Oriental". American Museum Novitates (3421): 1–47. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2003)421<0001:ansotr>2.0.co;2. hdl:2246/2850. S2CID 62795333.

- Weksler, M. (2006). "Phylogenetic relationships of oryzomyine rodents (Muroidea: Sigmodontinae): separate and combined analyses of morphological and molecular data". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 296: 1–149. doi:10.1206/0003-0090(2006)296[0001:PROORM]2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/5777. S2CID 86057173.

- Wilson, Don E.; Reeder, DeeAnn M. (16 November 2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0801882210. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

.jpg.webp)