| Pelagornis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstruction of a P. miocaenus skeleton at the NMNH. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | †Odontopterygiformes |

| Family: | †Pelagornithidae |

| Genus: | †Pelagornis Lartet, 1857 |

| Type species | |

| †Pelagornis miocaenus Lartet, 1857 | |

| Species | |

|

†P. miocaenus Lartet, 1857 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

see text | |

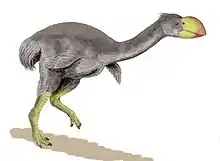

Pelagornis is a widespread genus of prehistoric pseudotooth birds. These were probably rather close relatives of either pelicans and storks, or waterfowl, and are placed here in the order Odontopterygiformes to account for this uncertainty.[1]

Taxonomy

Four species have been formally described, but several other named taxa of pseudotooth birds might belong in Pelagornis too. The type species Pelagornis miocaenus is known from Aquitanian (Early Miocene) sediments – formerly believed to be of Middle Miocene age – of Armagnac (France). The original specimen on which P. miocaenus was founded was a left humerus almost the size of a human arm. The scientific name – "the most unimaginative name ever applied to a fossil" in the view of Storrs L. Olson[2] – does in no way refer to the bird's startling and at that time unprecedented proportions, and merely means "Miocene pelagic bird". Like many pseudotooth birds, it was initially believed to be related to the albatrosses in the tube-nosed seabirds (Procellariiformes), but subsequently placed in the Pelecaniformes where it was either placed in the cormorant and gannet suborder (Sulae) or united with other pseudotooth birds in a suborder Odontopterygia.[3]

While P. miocaenus was the first pseudotooth bird species to be described scientifically, its congener Pelagornis mauretanicus was only named in 2008. It was a slightly distinct and markedly younger species. Its remains have been found in 2.5 Ma Gelasian (Late Pliocene/Early Pleistocene, MN17) deposits at Ahl al Oughlam (Morocco).[4]

Additional fossils are placed in Pelagornis, usually without assignment to species, mainly due to their large size and Miocene age. From the United States, such specimens have been found in the Middle Miocene Calvert Formation of Maryland and Virginia, and the contemporary Pungo River Formation of the Lee Creek Mine in North Carolina (though at least one other pelagornithid is probably represented among this material too). USNM 244174 (a tarsometatarsus fragment) was found near Charleston, South Carolina and assigned to P. miocaenus, and the slightly smaller left tarsometatarsal middle trochlea USNM 476044 might also belong here. A broken but fairly complete sternum probably of this genus, specimen LHNB (CCCP)-1, is known from the Serravallian-Tortonian boundary (Middle to Late Miocene) near Costa da Caparica in Portugal. Contemporary are certain specimens [5] from the Bahía Inglesa Formation of Chile, while other material from this formation[6] as well as remains from the Pisco Formation of Peru are from the Late Miocene to Early Pliocene.[7]

It is not clear whether the South American fossils – of similar size and age and not including directly comparable bones – are from one or two species. A very worn sternum and some other remains from the Miocene of Oregon as well as roughly contemporary material from California are sometimes assigned to Pelagornis, but this appears to be an error; if not of the contemporary North Pacific Osteodontornis, the specimen is better regarded as indeterminable. Given the distance in space and time involved, all Pacific material may well have been a species different from P. miocaenus or even from birds closer to Osteodontornis. Indeed, some of the older Bahía Inglesa Formation remains[8] tentatively referred to Pelagornis were at first assigned to the mysterious Pseudodontornis longirostris in error, and a proximal (initially misidentified as distal) humerus piece (CMNZ AV 24,960), from the Waiauan (Middle-Late Miocene) cliffs near the mouth of the Waipara River (North Canterbury, New Zealand) seems to differ little from either O. orri or P. miocaenus. The Pisco Formation specimens – which may be from the same species as the Bahía Inglesa ones, or from its direct descendant – on the other hand seem to be well distinct from Osteodontornis. It must be remembered, however, that the Isthmus of Panama had not been formed yet during the Miocene.[9]

Pelagornis sandersi was described in July 2014, whose fossil remains date from 25 million years ago, during the Chattian age of the Oligocene.[10][11] The only known fossil of P. sandersi was first uncovered in 1983 at Charleston International Airport, South Carolina, discovered by James Malcom, while working construction building a new terminal there. At the time the bird lived, 25 million years ago, global temperatures were higher, and the area where it was discovered was an ocean.[12][13] After excavation, the fossil of P. sandersi was catalogued and put in storage at the Charleston Museum, where it remained until it was rediscovered by paleontologist Dan Ksepka in 2010.[14][15] The bird is named after Albert Sanders, the former curator of natural history at the Charleston Museum, who led the excavation of P. sandersi.[16] It currently sits at the Charleston Museum, where it was identified as a new species by Ksepka in 2014.[11]

Synonyms and relationships

A humerus from the Muséum d'Histoire naturelle de Bordeaux was labelled "Pelagornis Delfortrii 1869". Though the name from the label had been listed in the synonymy of P. miocaenus, neither does it seem to be a validly established taxon nor was the specimen compared with P. miocaenus remains. It seems to refer to one of the syntypes of the procellariiform Plotornis delfortrii – found at Léognan (France) and also of Aquitanian age – from which that species was described in the 1870s by Alphonse Milne-Edwards: when the nomen nudum "Pelagornis delfortrii" is listed in the synonymy of P. miocaenus, the pseudotooth bird is claimed to be known from the Léognan deposits also, whereas it has not actually been found there. Pseudodontornis, meanwhile, is a generally Paleogene genus of huge pseudotooth birds. All its species are not uncommonly considered synonymous with earlier-described taxa. The (probably) Eo-Oligocene type species Pseudodontornis longirostris might belong in Pelagornis, though given its uncertain age and provenance a comparison with undisputed Pelagornis material – which is currently lacking – would seem to be necessary before such a step is taken. In that respect, Palaeochenoides mioceanus was also hypothesized to include P. longirostris, and would need to be compared with Pelagornis to see whether it does not belong here too.[17]

There has been little dedicated study of the relationships of Pelagornis, for while quite a lot of remains are known from the present genus, those of most other pseudotooth birds are few and far between and direct comparisons are further hampered by the damaged state of most remains. The large Gigantornis eaglesomei from the Middle Eocene Atlantic was established based on a broken but not too incomplete sternum and might actually belong in Dasornis. In Gigantornis the articular facet for the furcula consists of a flat section at the very tip of the sternal keel and a similar one set immediately above it at an outward angle, and the spina externa is shaped like an Old French shield in cross-section. The slightly smaller LHNB (CCCP)-1 has a less sharply protruding sternal keel, the articular facet for the furcula consists of a large knob at the forward margin, and the spina externa is narrow in cross-section. While these differences are quite conspicuous, the two fossils are clearly of closely related huge dynamically soaring seabirds, and considering the 30 million years or so that separate Gigantornis and LHNB (CCCP)-1, the Paleogene taxon may be very close to the Miocene bird's ancestor nonwithstanding their differences.[18]

In any case, the family name of the pseudotooth birds, Pelagornithidae, as the senior synonym has widely replaced the once-commonly used Pseudodontornithidae. It may be that Pseudodontornis belongs to a distinct lineage of these birds, and then the family name would perhaps be revalidated. Also, the presumed similarity between Dasornis[19] and the smaller Odontopteryx seems to be a symplesiomorphy that is not informative regarding their relationships to each other and with Pelagornis. Rather, it is likely that the huge pseudotooth birds form a clade, and in this case, Pseudodontornithidae like Cyphornithidae and Dasornithidae is correctly placed in the synonymy of Pelagornithidae even if several families were accepted in the Odontopterygiformes.[20]

Description

Size and wingspan

The sole specimen of P. sandersi has a wingspan estimated between approximately 6.06 and 7.38 m (19.9 and 24.2 ft),[10] giving it the largest wingspan of any flying bird yet discovered, twice that of the wandering albatross, which has the largest wingspan of any extant bird (up to 3.7 m (12 ft)).[21] In this regard, it supplants the previous record holder, the also extinct Argentavis magnificens. The skeletal wingspan (excluding feathers) of P. sandersi is estimated at 5.2 m (17 ft) while that of A. magnificens is estimated at 4 m (13 ft).[16][22]

The fossil specimens show that P. miocaenus was one of the largest pseudotooth birds, hardly smaller in size than Osteodontornis or the older Dasornis. Its head must have been about 40 cm (16 in) long in life, and its wingspan was probably more than 5 m (16 ft), perhaps closer to 6 metres (20 ft).

Skull

Like all members of the Pelagornithidae, P. sandersi had tooth-like or knob-like extensions of the bill's margin, called "pseudo-teeth," which would have enabled the living animal to better grip and grasp slippery prey. According to Ksepka, P. sandersi's teeth "don’t have enamel, they don’t grow in sockets, and they aren’t lost and replaced throughout the creature’s life span."[12] Unlike in its contemporary Osteodontornis but like in the older Pseudodontornis, between each two of Pelagornis's large "teeth" was a single smaller one. The salt glands inside the eye sockets were extremely large and well-developed in Pelagornis.

Postcranial skeleton

Pelagornis differed from Dasornis and its smaller contemporary Odontopteryx in having no pneumatic foramen in the fossa pneumotricipitalis of the humerus, a single long latissimus dorsi muscle attachment site on the humerus instead of two distinct segments, and no prominent ligamentum collaterale ventrale attachment knob on the ulna. Further differences between Odontopteryx and Pelagornis are found in the tarsometatarsus: in the latter, it has a deep fossa of the hallux' first metatarsal bone, whereas its middle-toe trochlea is not conspicuously expanded forward. From the humerus pieces of specimen LACM 127875, found in the Eo-Oligocene Pittsburg Bluff Formation near Mist, Oregon (United States), P. miocaenus differs in an external tuberosity that is not as much extended towards shoulder and that is separated from the elbow end by a wider depression. The head of the humerus is turned more to the inward side and the large protuberance found there is not as far towards the end. The Waipara River humerus mentioned above agrees with P. miocaenus in that respect. If the Oregon fossils are related to Cyphornis and/or Osteodontornis, and if the traits as found in P. miocaenus and the New Zealand specimen are apomorphic, the latter two may indeed be very close relatives.[23]

Paleobiology

P. sandersi had short, stumpy legs, and was possibly flying for the most part, by hopping and flying off cliff edges,[22] although volancy is still in the question. This is aided by its location being near coasts. Originally, there were controversies over whether or not P. sandersi would be able to fly. Previously, the assumed maximum wingspan of a flying bird was 17 ft (5.2 m), because it was hypothesized that above 17 ft, the power required to keep the bird in flight would surpass the power capacity of the bird's muscles. However, this calculation is based on the assumption that the bird in question stays aloft by repeatedly flapping its wings, whereas P. sandersi more likely glided on ocean air currents close to the water, which is less power-intensive than reaching high altitudes.[15][24] It has been estimated that it was able to fly at up to 60 km/h (37 mph).[22] P. sandersi's long wingspan and gliding power would have enabled it to travel long distances without landing while hunting.[13] Due to P. sandersi's size, the bird likely molted all of its flight feathers at once, similarly to a grebe, since larger feathers take longer to regrow.[13] P. sandersi is theorized to have glided and traveled similarly to a modern albatross, however, according to Dan Ksepka, its closest modern relatives are chickens and ducks.[14]

Some scientists expressed surprise at the idea that this species could fly at all, given that, at between 22 and 40 kg (48 and 88 lb), it would be considered too heavy by the predominant theory of the mechanism by which birds fly.[25] Dan Ksepka of the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center in Durham, North Carolina, who identified that the discovered fossils belonged to a new species, thinks it was able to fly in part because of its relatively small body and long wings,[26] and because it, like the albatross, spent much of its time over the ocean.[12] Ksepka is currently focused on solving how P. sandersi evolved and what caused the species to go extinct.[14]

Distribution

Fossils of Pelagornis have been found in:[27]

- Eocene

- Aridal Formation (Bartonian), Morocco

- La Meseta Formation, Seymour Island, Antarctica

- Oligocene

- Chandler Bridge Formation, South Carolina

- Miocene

- Black Rock Sandstone, Australia

- Bahía Inglesa Formation (Mayoan-Montehermosan), Chile

- Molasse Coquilliere Formation, France

- Calvert Formation, Virginia

- Waipara River mouth (Waiauan), Canterbury, New Zealand

- Pisco Formation (Chasicoan-Huayquerian), Peru

- Costa de Caparica or Fonte de Pipa, Tagus Basin, Portugal

- Castillo (Colhuehuapian-Santacrucian) and Capadare Formations (Laventan-Mayoan), Venezuela

- Pliocene

- Greta Formation, New Zealand

- Purisima Formation, California and Yorktown Formation, North Carolina

- Early Pleistocene

- Ahl al Oughlam, Morocco

References

- ↑ Bourdon (2005), Mayr (2009: p. 59)

- ↑ Olson (1985: p. 197)

- ↑ Lanham (1947), Brodkorb (1963: p. 262–263), Olson (1985: p. 197), Mlíkovský (2002: pp. 83–84)

- ↑ Mlíkovský (2009)

- ↑ MUSM 209 (a broken left humerus), MUSM 265 (a broken right humerus), MPC 1000 (a proximal right humerus end), and perhaps the additional remains MPC 1001 to 1006: Chávez et al. (2007)

- ↑ UOP/01/81 (first phalanx of the left second finger), UOP/01/79 and UOP/01/80 (damaged right tarsometatarsi), perhaps also a distal right coracoid; all from near Bahía Inglesa: Walsh (2000), Walsh & Hume (2001), Chávez et al. (2007)

- ↑ Proximal carpometacarpus and right humerus ends in the MNHN: Chávez et al. (2007)

- ↑ MPC 1001 to 1006 (various bill and skull pieces, a proximal left ulna end and two cervical vertebrae): Chávez et al. (2007)

- ↑ Scarlett (1972), Olson (1985: pp. 195-199), Goedert (1989), Rasmussen (1998), Mlíkovský (2002: p. 84), Rincón R. & Stucchi (2003), Bourdon (2005), Chávez et al. (2007), Mayr et al. (2008), NEO (2008), NMNH-DP [2009]

- 1 2 Ksepka, Daniel T. (7 July 2014). "Flight performance of the largest volant bird". PNAS. 111 (29): 10624–10629. doi:10.1073/pnas.1320297111. PMC 4115518. PMID 25002475.

- 1 2 Osborne, Hannah (July 7, 2014). "Pelagornis Sandersi: World's Biggest Bird Was Twice as Big as Albatross with 24 feet (7.3 m) Wingspan". International Business Times. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Feltman, Rachel (July 7, 2014). "A newly declared species may be the largest flying bird to ever live". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Charles Q. Choi (2014-07-07). "World's Largest Flying Bird Was Like Nothing Alive Today". livescience.com. Retrieved 2022-09-21.

- 1 2 3 "This Ancient Bird Had the Largest Wingspan Ever". Connecticut Public. 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2022-09-21.

- 1 2 Hu, Jane C. (2014-07-07). "The World's Largest Flying Bird Had a Wingspan the Length of Four People Laid Head to Toe". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 2022-09-21.

- 1 2 Choi, Charles Q. (July 7, 2014). "World's largest flying bird was like nothing alive today". Fox News. Fox News. Archived from the original on July 8, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- ↑ Brodkorb (1963: pp. 245, 263), Hopson (1964), Olson (1985: p. 198), Mlíkovský (2002: pp. 80, 82-83)

- ↑ Olson (1985: p. 196), Mayr (2009: p. 56, 58), Mayr et al. (2008)

- ↑ As Argillornis; see Mayr (2008)

- ↑ Olson (1985: p. 195), Mlíkovský (2002: p. 81), Bourdon (2005), Mayr (2009: p. 59)

- ↑ Morelle, Rebecca (July 7, 2014). "Fossil of 'largest flying bird' identified". BBC News. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Karim, Nishad (July 7, 2014). "Fossils dug up at airport may be largest flying bird ever found". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 8, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- ↑ Olson (1985: p. 198), Goedert (1989), Rincón R. & Stucchi (2003), Bourdon (2005), Mayr (2008), Mayr et al. (2008)

- ↑ "Biggest Flying Seabird Had 21-Foot Wingspan, Scientists Say". History. 2014-07-07. Archived from the original on September 21, 2022. Retrieved 2022-09-21.

- ↑ Hotz, Robert Lee (July 7, 2014). "Scientists Identify Largest Flying Bird". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on July 11, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- ↑ Khan, Amina (July 7, 2014). "Fossil's 21-foot wingspan shows Pelagornis was 'largest flying bird'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 8, 2014. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ↑ Pelagornis at Fossilworks.org

Bibliography

- Bourdon, Estelle (2005). "Osteological evidence for sister group relationship between pseudo-toothed birds (Aves: Odontopterygiformes) and waterfowls (Anseriformes)". Naturwissenschaften. 92 (12): 586–91. doi:10.1007/s00114-005-0047-0. PMID 16240103. S2CID 9453177. Electronic supplement (requires subscription)

- Brodkorb, Pierce (1963). "Catalogue of fossil birds. Part 1 (Archaeopterygiformes through Ardeiformes)". Bulletin of the Florida State Museum, Biological Sciences. 7 (4): 179–293.

- Chávez, Martín; Stucchi, Marcelo & Urbina, Mario (2007): El registro de Pelagornithidae (Aves: Pelecaniformes) y la Avifauna Neógena del Pacífico Sudeste [The record of Pelagornithidae (Aves: Pelecaniformes) and the Neogene avifauna of the southeast Pacific]. Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Études Andines 36(2): 175–197 [Spanish with French and English abstracts]. PDF fulltext

- Goedert, James L. (1989). "Giant Late Eocene Marine Birds (Pelecaniformes: Pelagornithidae) from Northwestern Oregon". Journal of Paleontology. 63 (6): 939–944. doi:10.1017/S0022336000036647. JSTOR 1305659. S2CID 132978790.

- Hopson, James A. (1964). "Pseudodontornis and other large marine birds from the Miocene of South Carolina". Postilla. 83: 1–19.

- Lanham, Urless N. (1947). "Notes on the phylogeny of the Pelecaniformes" (PDF). Auk. 64 (1): 65–70. doi:10.2307/4080063. JSTOR 4080063.

- Mayr, Gerald (2008). "A Skull of the Giant Bony-Toothed Birddasornis(Aves: Pelagornithidae) from the Lower Eocene of the Isle of Sheppey". Palaeontology. 51 (5): 1107–1116. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00798.x.

- Mayr, Gerald (2009): Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg & New York. ISBN 3-540-89627-9

- Mayr, Gerald; Hazevoet, Cornelis J.; Dantas, Pedro & Cachāo, Mário (2008). "A sternum of a very large bony-toothed bird (Pelagornithidae) from the Miocene of Portugal". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (3): 762–769. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[762:ASOAVL]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 20491001. S2CID 129386456.

- Mayr, Gerald & Rubilar-Rogers, David (2010). "Osteology of a new giant bony-toothed bird from the Miocene of Chile, with a revision of the taxonomy of Neogene Pelagornithidae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (5): 1313–1330. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.501465. S2CID 84476605.

- Mlíkovský, Jirí (2002): Cenozoic Birds of the World, Part 1: Europe. Ninox Press, Prague.

- Mlíkovský, Jirí (2009). "Evolution of the Cenozoic marine avifaunas of Europe" (PDF). Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien A. 111: 357–374. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-12. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- NASA Earth Observatory (NEO) (2008): Panama: Isthmus that Changed the World. Version of 2008-SEP-22. Retrieved 2009-SEP-24.

- National Museum of Natural History Department of Paleobiology (NMNH-DP) [2009]: Paleobiology Collections Search. Version of 2009-AUG-07. Retrieved 2009-AUG-22.

- Olson, Storrs L. (1985): The Fossil Record of Birds. In: Farner, D. S.; King, J. R. & Parkes, Kenneth C. (eds.): Avian Biology 8: 79–252.

- Rasmussen, Pamela C. (1998). "Early Miocene Avifauna from the Pollack Farm Site, Delaware" (PDF). Delaware Geological Survey Special Publication. 21: 149–151.

- Rincón R., Ascanio D. & Stucchi, Marcelo (2003): Primer registro de la familia Pelagornithidae (Aves: Pelecaniformes) para Venezuela [First record of Pelagornithidae family from Venezuela]. Boletín de la Sociedad Venezolana de Espeleología 37: 27–30 [Spanish with English abstract]. PDF fulltext

- Scarlett, R. J. (1972). "Bone of a presumed odontopterygian bird from the Miocene of New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 15 (2): 269–274. doi:10.1080/00288306.1972.10421960.

- Walsh, Stig A. (2000): Big-chested birds – exciting new avian material from the Neogene of Chile. Talk held at the 48th Annual Symposium of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Comparative Anatomy, 1 September 2000, Portsmouth, UK.

- Walsh, Stig A. & Hume, Julian P. (2001). "A new Neogene marine avian assemblage from north-central Chile" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (3): 484–491. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0484:ANNMAA]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 64680575.

External links

- Photo of some Calvert Formation specimens (and some of the disputed Oregon fossils) at National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 2009-AUG-21.

- From the collections, Part 4 - Article on Calvert Formation material of ?Pelagornis sp. 2. at Virginia Museum of Natural History Retrieved 2010-SEP-18.

- Lichtman, Flora (2023-05-31). "This Massive Scientific Discovery Sat Hidden in a Museum Drawer for Decades". Scientific American. Retrieved 2023-05-31.