| Pallikaranai Marsh | |

|---|---|

Pallikaranai Marsh at Sholinganallur | |

Pallikaranai Marsh | |

| Location | Pallikaranai, Chennai, India |

| Coordinates | 12°56′15.72″N 80°12′55.08″E / 12.9377000°N 80.2153000°E |

| Lake type | Wetland |

| Catchment area | 235 km2 (91 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | India |

| Max. length | 15 km (9.3 mi) |

| Max. width | 3 km (1.9 mi) |

| Surface area | 80 km2 (31 sq mi) |

| Water volume | 9 km3 (2.2 cu mi) |

| Surface elevation | 5 m (16 ft) |

| Settlements | Chennai |

| Official name | Pallikaranai Marsh Reserve Forest |

| Designated | 8 April 2022 |

| Reference no. | 2481[1] |

Pallikaranai Marsh is a freshwater marsh in the city of Chennai, India. It is situated adjacent to the Bay of Bengal, about 20 kilometres (12 mi) south of the city centre, and has a geographical area of 80 square kilometres (31 sq mi). Pallikaranai marshland is the only surviving wetland ecosystem of the city and is among the few and last remaining natural wetlands of South India.[2] It is one of the 94 identified wetlands under National Wetland Conservation and Management Programme (NWCMP) operationalised by the Government of India in 1985–86 and one of the three in the state of Tamil Nadu, the other two being Point Calimere and Kazhuveli. It is also one of the prioritised wetlands of Tamil Nadu.[3] The topography of the marsh is such that it always retains some storage, thus forming an aquatic ecosystem. A project on 'Inland Wetlands of India' commissioned by the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India had prioritised Pallikaranai marsh as one of the most significant wetlands of the country.[4] The marsh contains several rare or endangered and threatened species and acts as a forage and breeding ground for thousands of migratory birds from various places within and outside the country. The number of bird species sighted in the wetland is significantly higher than the number at Vedanthangal Bird Sanctuary.[5]

Indiscriminate dumping of toxic solid waste along the road, discharge of sewage, and construction of buildings, railway stations and a new road to connect Old Mahabhalipuram Road and Pallavaram have shrunk the wetland to a great extent. In 2007, as an effort to protect the remaining wetland from shrinking further, the undeveloped areas in the region were notified as a reserve forest.[6][7][8] A 2018 study showed that about 60 percent of the native species in the wetland, including hoorahgrass (Fimbristylis), dwarf copperleaf or Ponnanganni keerai (Alternanthera sessilis), floating lace plant or kottikizhangu (Aponogeton natans), wild paddy (Oryza rufipogon), crested floating heart (Nymphoides), and nut grass (Cyperus), have been replaced by invasive species.[9]

Location and ecology

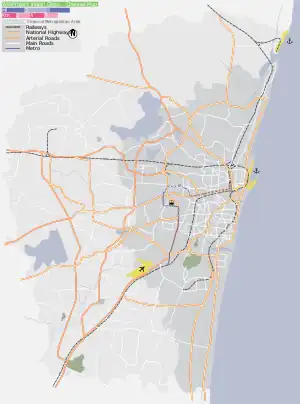

The marshland is located along the Coromandel Coast south of the Adyar Estuary, serving as an aquatic buffer of the flood-prone Chennai and Chengalpattu districts.[10] It is surrounded by the expressway of Old Mahabalipuram Road and the residential areas of Perungudi, Siruseri, Pallikaranai, Madipakkam, Velachery and Taramani. An extensive low-lying area covered by a mosaic of aquatic grass species, scrub, marsh, and water-logged depressions, it is connected to 31 different water bodies, all of which release surplus water into the marsh during the monsoons. It has a catchment of 235 square kilometres (91 sq mi) that includes the urban sprawls of Velachery, Pallikaranai and Navalur. The terrain of the area is generally plain with an average altitude of about 5 metres (16 ft) above mean sea level. It receives an annual rainfall of 1,300 millimetres (51 in), mostly during the northeast monsoon (September–November), but also during the southwest monsoon (June–August). Temperature ranges from 35 to 42 °C (95 to 108 °F) during the summer, and from 25 to 34 °C (77 to 93 °F) in the winter. A large part of the southern region of Chennai was historically a flood plain as evidenced by the soil type of the region, which is described as recent alluvium and granite gneiss. The entire landscape comprises a coastal plain with intermittent and overlapping habitat types of cultivated land, wetlands and scrub forests. The wetlands comprises a large marsh (the Pallikaranai marsh), smaller satellite wetlands, large tracts of pastureland and patches of dry forests. The marsh has been cut into two for a road with no free flow underneath.[11] Spread over 50 square kilometres (19 sq mi) at the time of Independence in the 1940s, about 90% of the wetland was lost as the city expanded and it continued shrinking at an alarming rate. The marshland has shrunk over the last four decades following the creation of residential areas around it, including Perungudi, Siruseri, Pallikaranai, Madipakkam, Taramani and Velachery.[12] Nearly a decade ago, about 120 species of birds were sighted at the marsh. However, their population has sharply decreased now due to various ecological disturbances in the region. The original expanse of the marsh in 1965 was about 5,500 hectares (14,000 acres).[13] The expanse estimated on the basis of the Survey of India toposheet of 1972 and aerial photographs (Corona) of 1965 was about 900 hectares (2,200 acres), which has shrunk to about 600 hectares (1,500 acres).[4][14] As of 2021, the marsh extends up to Sholinganallur Road, covering an area of 695.85 hectares.[10][15]

| Group | Number of species |

|---|---|

| Plants | 114 |

| Birds | 115 |

| Mammals | 10 |

| Reptiles | 21 |

| Fishes | 46 |

| Amphibians | 10 |

| Molluscs | 9 |

| Crustaceans | 5 |

| Butterflies | 7 |

| Total | 337 |

Excess rainwater is drained into the sea through a channel called the Oggiyam Madavu, a contiguous portion of the marsh at Oggiyam Thorapakkam draining into the Buckingham Canal, which in turn discharges into the Kovalam estuary. Locally known as Kazhiveli (a generic Tamil name for marshes and swamps), the marsh drained about 250 square kilometres (97 sq mi), through two outlets, namely, the Okkiyam Madavu and the Kovalam creek. Remnant forests can be observed within the Theosophical Society campus, Guindy National Park–IIT complex and the Nanmangalam Reserve Forest.

The heterogeneous ecosystem of the marshland supports about 337 species of floras and faunas.[16] Of the faunal groups, birds, fishes and reptiles are the most prominent. Pallikaranai marsh is home to 115 species of birds, 10 species of mammals, 21 species of reptiles, 10 species of amphibians, 46 species of fishes, 9 species of molluscans, 5 species of crustaceans, and 7 species of butterflies. About 114 species of plants are found in the wetland including 29 species of grass. These plant species include some exotic floating vegetation such as water hyacinth and water lettuce, which are less extensive now and highly localised.[2] The region has a bird bio-diversity about 4 times that of Vedanthangal. It is also home to some of the most endangered reptiles such as the Russell's viper and birds such as the glossy ibis, grey-headed lapwings[17] and pheasant-tailed jacana. Cormorants, darters, herons, egrets, open-billed storks, spoonbills, white ibis, little grebe, Indian moorhen, black-winged stilts, purple moorhens, warblers, coots and dabchicks have been spotted in large numbers in the marshland.[18][19] The marsh has also had the distinction of new records of reptiles and plants being described, on a rather regular basis since 2002.[20]

Another rare species spotted in the region is the white-spotted garden skink having appeared for the first time in Tamil Nadu. Fish such as dwarf gourami and chromides that are widely bred and traded worldwide for aquaria, naturally occur in Pallikaranai. Other estuarine fauna present at the marsh includes the windowpane oyster, mud crab, mullet, halfbeak and green chromide.[21]

Encroachments and pollution

The external manipulation of the wetland system began in 1806 with the construction of the 422-kilometre (262 mi) Buckingham Canal.[4] The marshland experienced several major construction activities, ranging from the National Institute of Ocean Technology, the Centre of Wind Energy Technology, Chennai's Mass Rapid Transport System, and flyovers to construction of buildings for educational institutions, IT parks, restaurants, shopping malls, and hospitals, which affected free flow of water. The land occupied by the corporation is 200 acres (81 ha), including 30 acres (12 ha) where a waste management plant is planned.[22] The locals started using the stagnant water in this part of the marsh as a bathing ghat and as a grazing ground for their cattle.

The existing sewage treatment and disposal facility for south Chennai is located on the immediate periphery and within the marshland. A large-scale sewage treatment facility of the Alandur municipality is also located on the premises.[23] About 32 million litres (8,500,000 US gal) of untreated sewage was being released every day at Thorapakkam by Metrowater, which contaminated water quality. In addition, garbage collected from the city was dumped close to the sewage-letting point.[24] The marshland also houses one of Chennai's largest official dump sites. Over 250 acres (100 ha) of the marsh is choked by half of the city's garbage. The Chennai Corporation dumps 2,000 tonnes (2,200 short tons) of waste into the marsh daily. This has resulted in leaching of heavy metals in the marsh, including chromium, lead, iron, manganese, cobalt, nickel, copper, zinc and cadmium from the 172-hectare Perungudi dumpyard developed by the city corporation. Chromium content in the ground water, for instance, has been found to be varying between 1.43 mg/L and 2.8 mg/L during the dry and wet seasons, which makes the water unsuitable for drinking, agriculture and discharge into inland surface water.[25]

Despite several court rulings, burning of garbage continued unabated at the marsh and the adjacent area of Perungudi.[26] All these led to a decrease in the estuarine fauna. Official statistics reveal that, in the absence of source segregation of waste, the dumpyard is eating into 4 hectares (9.9 acres) of marshland every year.

The dumpyard originally covered 19 acres (7.7 ha) in Sevaram village at Perungudi in 1970. By the mid-1980, the area was completely filled up and the corporation shifted to the present location in Pallikaranai. While the marsh which originally covered an area of 5,000 hectares (12,000 acres) had shrunk into 593 hectares (1,470 acres) by 2002, the corporation's dumpyard that covered 56 hectares (140 acres) in 2002 had expanded to 136 hectares (340 acres) in 2007 and is expanding constantly. Over 4,500 tonnes (5,000 short tons) of garbage are dumped daily in the marsh region from the southern part of the city. In addition, industrial waste is dumped in heaps along the water bodies.[27]

The SIPCOT Area Community Environmental Monitors group analysed an ambient air sample collected downwind of the garbage dump in Pallikaranai and found that it contained at least 27 chemicals, 15 of which greatly exceed health-based standards set by the United States Environmental Protection Agency. Three of the 27 chemicals are also known to cause cancer in humans and were found in quantities as high as 34,000 times above safe levels.[28][29] A research by the Anna University revealed a large quantity of metallic sedimentation discharged from the Perungudi dumpyard being deposited in the marshland, affecting its biodiversity.[30]

Conservation efforts

In 2002, the Tamil Nadu Pollution Control Board commissioned a study to find out the total area of the marsh and its habitat quality and suggested interventional methods. The survey revealed the presence of 275 species of flora and over 100 species of birds in the wetland. On 20 February 2003, the Kancheepuram district collector issued a gazette notification announcing that 548 hectares (1,350 acres) of the marsh area was classified as Protected Land. In late 2005, the government constituted a high-level committee to restore the ecosystem, and in the summer of 2006 the locals formed an environment committee to protect the wetland. In 2007, an eight-member team from Freiburg University in Germany conducted a study on the physical and social features of the marsh.[31]

As a first real effort to protect the wetland, the state declared 317 hectares (780 acres) of the marsh as a reserve forest on 9 April 2007 (Gazettee notification G.O.Ms.No.52, dated 9 April 2007) under the Forest (Conservation) Act of 1980 and brought under the jurisdiction of the District Forest Officer–Kanchipuram (Tambaram range), a separate range in Chengalpet Forest Division at Kancheepuram with headquarters at Pallikaranai.[32] The Kancheepuram district authorities transferred the land to the forest department. However, researchers suggested that an additional 150 ha on both sides of the Thoraipakkam–Tambaram road bisecting the marsh be declared a reserve forest as birds, especially several varieties of ducks, came there for feeding. Named Pallikaranai Swamp Forest Block, it is the 17th reserve forest area in the Tambaram Range, whose reserve forest area goes up to 56.27 square kilometres (21.73 sq mi) with this addition.

The first scientific bird census in the state conducted in January 2010 revealed that birds still visit the marsh despite the non-stop dumping by the city corporation.

Anticipating the obstruction of the water flow from north to south by the growing garbage mounds, the government directed the civic body to transfer 150 hectares (370 acres) to the forest department. After this, the state government will acquire patches of land in the northern (adjacent to Velachery–Tambaram road) and southeastern parts of the marshland, measuring about 127 hectares (310 acres), to protect the ecosystem in its totality from becoming an open dumpyard.[33] Save Pallikaranai, a campaign for protecting an ecologically sensitive environment despite urban pressures, has achieved significant success owing to people's participation, sustained media support and a responsive government.

There was a proposal to turn the Pallikaranai marsh into a wetland centre by networking with international agencies to attract funds for its protection and restoration.

In 2011, an adaptive management plan for the Pallikaranai marshland estimated at a cost of ₹ 150 million was prepared by Chennai-based NGO called Care Earth, an organisation working towards ecological conservation,[34] which has been sent to the Union Ministry by the state department and is pending for approval.[23] The plan recommends setting up digital boards, depictive murals, viewing decks and towers connected through walkways, aquaria, viewing telescopes, night-vision cameras and camera traps.[14]

The State Forest Department has prepared a comprehensive five-year plan to protect the marshland. Initially, desilting and dredging work at a cost of ₹ 10 million per year would be taken up. The plan also includes forming a bio-shield costing ₹ 1.087 million annually, removal of aquatic weeds at a cost of ₹ 2.5 million for 5 years, mound planting at a cost of ₹ 2.75 million for 3 years, linear planting along the boundary at a cost of ₹ 1.65 million and forming flood bund and trail paths at a cost of ₹ 34 million. Apart from this, the department is also considering allocation of ₹ 5 million for conducting research projects on the marshland, about ₹ 6 million towards a bird census, a 3-kilometre (1.9 mi) boardwalk path in a period of 3 years at a cost of ₹ 30 million, watchtowers at two places in a period of 2 years at a cost of ₹ 2 million, and a wetland centre at a cost of ₹ 4 million. In addition, there is a proposal for creating roadside parks, installing signage, and conducting awareness camps during the project implementation period at a cost of ₹ 4 million as part of the initiative.[35]

The State Forest Department has made the preliminary move to get the marshland declared as a Ramsar site by submitting a compliance report to the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands.[2]

In 2010, steps were taken to facilitate birdwatching at the marsh. Fencing has been completed in the area for over half a kilometre along the marshland. The entire stretch of 1.7 kilometres (1.1 mi) would be provided with benches for the benefit of birdwatchers. The forest department is constructing a compound wall on the southern portion of the marsh covering a distance of 5 kilometres (3.1 mi).[36] A 870-metre (2,850 ft) portion of the boundary wall has been completed on the Sholinganallur side of the Pallikaranai marsh to protect the wetland from encroachers.[32]

In September 2011, the civic body initiated the process of handing over the marshland following a request from the Forest Department. The Forest Department, which plans to undertake restoration of the eco-sensitive Pallikaranai marshland, will get 421 acres (170 ha) for the purpose from the Chennai Corporation. The area to be handed over is on the southern side of Radial Road near NIOT junction. The civic body is planning to use only around 200 acres (81 ha) elsewhere in the marshland for its solid waste management project in Perungudi.[12][37]

On 26 March 2012, the state government announced that the scheme of restoring and conserving the marshland would be implemented in the coming year with an outlay of ₹ 50 million. Setting up of a Pallikaranai Marsh Conservation Society has also been proposed.[38]

In 2012, eco-restoration work began on about 100 acres of land near the southernmost point of the marshland. The completion of the eco-restoration project will take five years and cost about ₹ 150 million. A water course spread over two hectares is being spruced up. A bund for a distance of more than 3 km has been planned, in addition to an observation centre, an interpretation centre where photographs of birds that visit the marshland will be displayed, and planting of a few thousand saplings of arjuna (neer maththi), portia (poovarasan), bamboo (moongil) and rosewood (sisu).[5]

In March 2018, the state government announced that it would commence the eco-restoration of 695 hectares of the wetland under the National Adaptation Fund for Climate Change to be implemented over five years from 2018 to 2023 at a cost of ₹1656.8 million.[39] The reserve forest has been designated as a protected Ramsar site since 2022.[1]

Ecological park

A 2.5-acre ecological park inside the Pallikaranai marsh was opened in December 2021 at a cost of ₹ 200 million. The park has a 2-km-long walking trail for bird watching and public green spaces enclosed within a 1,700-metre compound wall. The marshland consists of four watch towers. These are located on the Thoraippakkam–Pallavaram Radial Road, on the eastern side, and on the northern side of the marsh.[10][15]

Incidents

On 19 March 2011, a fire started on a patch of land opposite Kamakshi Memorial Hospital around 4 pm local time and spread to 15 locations in the marsh.[40] Patches measuring more than 10 acres (4.0 ha) of the protected 200-acre (81 ha) marshland were burnt in the fire lasting for about 5 hours. Several nesting migratory birds were feared killed in the incident.[41]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Pallikaranai Marsh Reserve Forest". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Forest Department makes first move to get Pallikaranai marsh declared Ramsar site". The Hindu. 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ↑ "Wetlands" (PDF). ENVIS Newsletter. Chennai: Department of Environment, Government of Tamil Nadu. 7 (4): 1–8. March 2011. ISSN 0974-133X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Management Plan—Conservation of Pallikaranai Marsh". nammapallikaranai.org. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- 1 2 Manikandan, K. (27 July 2012). "Pallikaranai wetland in makeover mode". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ "Pallikaranai swamp". Conservation of Wetlands, Wetlands of Chennai. C.P.Ramaswami Environmental Education Centre. 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ↑ Oppili, P. (13 April 2009). "Restoration eluding Pallikaranai marsh". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Manikandan, K. (21 April 2007). "Major part of marshland now reserve forest area". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 27 April 2007. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- ↑ Lakshmi, K. (20 January 2019). "Indigenous flora in city wetlands under threat". The Hindu. Chennai: Kasturi & Sons. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Tamil Nadu seeks Ramser site clearance for Pallikaranai marshland". DT Next. Chennai: Daily Thanthi. 10 December 2021. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ↑ Padmanabhan, Geeta (9 January 2012). "Chennai's eco spots". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- 1 2 Xavier Lopez, Aloysius (16 September 2011). "Forest Department to get marshland". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ "Pallikaranai marsh has shrunk to a tenth of its size since 1965: Amicus Curiae". The Hindu. Chennai: Kasturi & Sons. 20 August 2019. p. 2. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- 1 2 Sreevatsan, Ajai (3 May 2011). "Pallikaranai marshland management plan likely". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- 1 2 Oppili, P. (10 December 2021). "CM to inaugurate Pallikaranai ecological park". The Times of India. Chennai. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ↑ Vencatesan, Jayshree (10 August 2007). "Protecting wetlands" (PDF). Current Science. 93 (3): 288–290. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Ramanan, Revathi (28 February 2011). "Rare grey-headed lapwing spotted in Pallikaranai marsh". The Times of India. Chennai. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Janardhanan, Arun (20 March 2011). "Fire at Pallikaranai marsh sparks calls for handing it over to forest dept". The Times of India. Chennai. Archived from the original on 8 September 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Raj; et al. (July 2010). "Consolidated checklist of birds in the Pallikaranai Wetlands, Chennai, India" (PDF). Journal of Threatened Taxa. 2 (8): 1114–1118. doi:10.11609/jott.o2220.1114-8. ISSN 0974-7907. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ "Pallikaranai Marsh, Chennai, Tamil Nadu". Migrant Watch. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ "Move to make Pallikaranai marsh 'protected wetland'". The Hindu. Chennai. 16 July 2002. Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Janardhanan, Arun (12 August 2011). "Pallikaranai restoration plan ignores half the marsh". The Times of India. Chennai. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- 1 2 Chandrasekar, Gokul (21 May 2011). "Finally, a plan to save Pallikaranai marsh". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Oppili, P. (22 October 2003). "Team visits Pallikaranai marsh". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 10 November 2003. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Lopez, Aloysius Xavier (28 April 2018). "Forest officials ask Corporation to stop dumping of waste". The Hindu. Chennai: Kasturi & Sons. p. 5. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ↑ TNN (16 July 2009). "Garbage still being burnt at Pallikaranai, says HC panel". The Times of India. Chennai. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Neeraja, Sangeetha (9 December 2009). "Pallikaranai marsh turns dumpyard". Express Buzz. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- ↑ Community Environmental Monitoring (2 December 2005). Choking in Garbage. SIPCOT. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Jayaprakash; et al. (2010). "Accumulation of total trace metals due to rapid urbanization in microtidal zone of Pallikaranai marsh, South of Chennai, India". Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 170 (1–4): 609–629. doi:10.1007/s10661-009-1261-6. PMID 20052614. S2CID 41925890.

- ↑ Mariappan, Julie (22 October 2011). "Forest dept to recover 100 ha of Pallikaranai marshland, Restoration of Eco-Sensitive Area to Cost Rs. 15.8 Crore". Times of India epaper. Chennai: The Times Group. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ "German researchers to study Pallikaranai marsh". The Hindu. Chennai. 6 January 2007. Archived from the original on 8 January 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- 1 2 Mariappan, Julie (23 March 2011). "Marshland yet to be notified as reserve forest". The Times of India epaper. Chennai: The Times Group. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ TNN (5 February 2010). "More area of Pallikaranai marsh to be protected". The Times of India. Chennai. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ "Summary of Program Areas, Projects and Highlights of Achievement". Care Earth Trust. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Oppili, P. (7 August 2011). "Comprehensive plan to protect Pallikaranai marsh". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Oppili, P. (13 August 2010). "Steps on to facilitate birdwatching at Pallikaranai marsh". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Xavier Lopez, Aloysius (17 May 2012). "Transfer of 300 acres of marshland to speed up Pallikaranai master plan". The Hindu. Chennai. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ↑ "Pallikaranai Marsh to get Rs. 5 crore". The Hindu. Chennai. 27 March 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ↑ "Mega City Mission to be revived". The Hindu. Chennai: Kasturi & Sons. 16 March 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Nesting birds feared dead in Pallikaranai marsh fire". The Hindu. Chennai. 21 March 2011. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ TNN (20 March 2011). "Fire rages across eco-sensitive Pallikaranai marsh for 5 hours". The Times of India. Chennai. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2011.