Historic flag of the Palatinate | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| The Palatinate, Pennsylvania Dutch Country, Germantown, Philadelphia, New York, USA | |

| Languages | |

| Palatine German | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholic, Lutheran, German Reformed | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Fancy Dutch, Pennsylvania Dutch, New York Dutch, German Americans, Hessians |

Palatines (Palatine German: Pälzer) are the citizens and princes of the Palatinates of the Holy Roman Empire, controlled directly by the Holy Roman Emperor.[1][2][3] After the fall of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the Palatine nationality came to refer specifically to people of the Rhenish Palatinate, known simply as "the Palatinate".[4]

American Palatines, including the Pennsylvania Dutch and New York Dutch, have maintained a presence in the United States since 1632, and are collectively known as "Palatine Dutch" (Palatine German: Pälzisch Deitsche).[5][6][7]

Holy Roman Nationality

Paladins

The term palatine or palatinus was first used in the Roman Empire for chamberlains of the emperor (e.g. Chamberlain of the Holy Roman Church) due to their association with the Palatine Hill, the home where Roman emperors lived since Augustus Caesar (and whence "palace").[8]

After the fall of Ancient Rome, a new feudal type of title known simply as palatinus, came into use. The comes palatinus (Count palatine) assisted the Holy Roman Emperor in his judicial duties and at a later date administered many of these himself. Other counts palatine were employed on military and administrative work.[9]

The Holy Roman Emperor sent the counts palatine to various parts of his empire to act as judges and governors; the states they ruled were called Palatinates.[10] Being in a special sense the representatives of the Holy Roman Emperor, they were entrusted with more extended power than ordinary counts. In this way came about the later and more general use of the word "palatine", its application as an adjective to persons entrusted with royal Holy Roman powers and privileges—and also to the states and people they ruled over.[9]

Holy Roman Palatinates

Counts palatine were the permanent representatives of the Holy Roman Emperor, in a palatial domain (Palatinate) of the crown. There were dozens of these royal palatinates (Pfalzen) throughout the early empire, and the emperor would travel between them, as there was no imperial capital.

In the empire, the term count palatine was also used to designate the officials who assisted the emperor in exercising the rights which were reserved for his personal consideration,[9] like granting arms. They were called imperial counts palatine (in Latin comites palatini caesarii, or comites sacri palatii; in German, Hofpfalzgrafen). Both the Latin form (Comes) palatinus and the French (comte) palatin have been used as part of the full title of the dukes of Burgundy (a branch of the French royal dynasty) to render their rare German title Freigraf, which was the style of a (later lost) bordering principality, the allodial County of Burgundy (Freigrafschaft Burgund in German), which came to be known as Franche-Comté.

During the 11th century, some imperial palatine counts became a valuable political counterweight against the mighty duchies. Surviving old palatine counties were turned into new institutional pillars through which the imperial authority could be exercised. By the reigns of Henry the Fowler and especially of Otto the Great, comites palatini were sent into all parts of the country to support the royal authority by checking the independent tendencies of the great tribal dukes. Apparent thereafter was the existence of a count palatine in Saxony, and of others in Lorraine, in Bavaria and in Swabia, their duties being to administer the royal estates in these duchies.[9]

Next to the Dukes of Lotharingia, Bavaria, Swabia and Saxony, who had become dangerously powerful feudal princes, loyal supporters of the Holy Roman Emperor were installed as counts palatine.

The Lotharingian palatines out of the Ezzonian dynasty were important commanders of the imperial army and were often employed during internal and external conflicts (e.g. to suppress rebelling counts or dukes, to settle frontier disputes with the Hungarian and the French kingdom and to lead imperial campaigns).

Although a palatinate could be rooted for decades into one dynasty, the office of the palatine counts became hereditary only during the 12th century. During the 11th century the palatinates were still regarded as beneficia, non-hereditary fiefs. The count palatine in Bavaria, an office held by the family of Wittelsbach, became duke of this land, the lower comital title being then merged into the higher ducal one.[9] The Count Palatine of Lotharingia changed his name to Count Palatine of the Rhine in 1085, alone remaining independent until 1777. The office having become hereditary, Pfalzgrafen were in existence until the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806.[9] The palatinate of Saxony merged with the Electoral Duchy of Saxony. The Palatinate of the Rhine became an electorate, and both were Imperial Vicars.

List of Palatinates

Palatinate of Champagne

King Lothar of France (954–986) gave Odo I, Count of Blois, one of his most loyal supporters in the struggle against the Robertians and the Counts of Vermandois, in 976 the title of count palatine. The title was later inherited by his heirs, and when they died out, by the Counts of Champagne.

Palatinate of Bavaria

.svg.png.webp)

Originally, the counts palatine held the County Palatine (around Regensburg) and were subordinate to the Dukes of Bavaria, rather than to the king. The position gave its holder a leading position in the legal system of the duchy.

- Meginhard I, Count Palatine of Bavaria in 883

- Arnulf II (d. 954), son of Duke Arnulf I of Bavaria, constructed Scheyern Castle around 940

- Berthold (d. 999), son of Arnulf II, Count Palatine of Bavaria between 954 and 976 with interruptions, ancestor of the Counts of Andechs

- Hartwig I (d. 985), Count Palatine of Bavaria from 977 until his death

- Aribo I (d. c. 1020, son-in-law of Hartwig I, Count Palatine of Bavaria from 985 until his death

- Hartwig II (d. 1027), son of Aribo I, Count Palatine of Bavaria from 1020 to 1026

- Aribo II (d. 1102), son of Hartwig II, Count Palatine of Bavaria from 1026 to 1055

- Kuno I (d. c. 1082/1083), Count Palatine of Bavaria

- Rapoto I (d. 1099), Count Palatine of Bavaria from c. 1083 to 1093

- Engelbert I (d. 1122), nephew of both of Aribo II's wives, Count Palatine of Bavaria from 1099 to 1120

- Otto IV (c. 1083 – 1156), probably a descendant of Arnulf II, Count Palatine of Bavaria from 1120 until his death. He moved his residence from Scheyern Castle to Wittelsbach Castle and founded the House of Wittelsbach.

- Otto V (c. 1117 – 1183), Count Palatine of Bavaria from 1156 to 1180. He became Duke of Bavaria in 1180 as Otto I; his descendants ruled the Duchy until 1918.

- Otto VII (d. 1189), younger son of Otto IV, Count Palatine of Bavaria from 1180 until his death

- Otto VIII (d. 1209), son of Otto VII, Count Palatine of Bavaria from 1189 to 1208, infamous for murdering King Philip of Germany in 1208

- Rapoto II (d. 1231), brother-in-law of Otto VIII, Count Palatine of Bavaria from 1208 until his death

- Rapoto III (d. 1248), son of Rapoto II, Count Palatine of Bavaria from 1231 until his death. He was the last count palatine; after his death the Duke of Bavaria assumed the rights and possessions of the counts palatine.

Palatinate of Lorraine

- Wigeric (915 – before 922), Count Palatine of Lotharingia and Count in the Bidgau

- Gottfried (c. 905 – after 949), Count Palatine of Lotharingia and Count in the Jülichgau

From 985, the Ezzonids held the title:

- Herman I (d. before 996), Count Palatine of Lotharingia and Count in the Bonngau, the Eiffelgau, the Zülpichgau and the Auelgau

- Ezzo (d. 1034), son of Herman I, Count in the Auelgau and the Bonngau, Count Palatine of Lotharingia from 1020, married Mathilda of Saxony, the daughter of Emperor Otto II

- Otto (d. 1047), son of Ezzo, Count Palatine of Lotharingia from 1035 to 1045, then Duke of Swabia as Otto II from 1045 until his death

- Henry I (d. 1061), son of Ezzo's brother Hezzelin I, Count Palatine of Lotharingia from 1045 to 1060

- Herman II (1049–1085), son of Henry I, Count Palatine of Lotharingia from 1061 to 1085 (until 1064 under the guardianship of Anno II, Archbishop of Cologne), also Count in the Ruhrgau and the Zülpichgau and Count of Brabant

The County Palatine of Lotharingia was suspended by the Emperor. Adelaide of Weimar-Orlamünde, Herman II's widow, remarried to Henry of Laach. Abt. 1087 he was assigned in the newly created office of Count Palatine of the Rhine.

Rhenish Palatinate

In 1085, after the death of Herman II, the County Palatine of Lotharingia lost its military importance in Lorraine. The territorial authority of the Count Palatine was reduced to his territories along the Rhine. Consequently, he is called the Count Palatine of the Rhine after 1085.

The Golden Bull of 1356 made the Count Palatine of the Rhine an Elector. He was therefore known as the Electoral Palatinate.

Palatinate of Saxony

.svg.png.webp)

In the 10th century the Emperor Otto I created the County Palatine of Saxony in the Saale-Unstrut area of southern Saxony. The honour was initially held by a Count of Hessengau, then from the early 11th century by the Counts of Goseck, later by the Counts of Sommerschenburg, and still later by the Landgraves of Thuringia:

- Adalbero (d. 982) was a Count in the Hessengau and in the Liesgau, Count Palatine of Saxony from 972,

- Dietrich (d. 995), probably a son of Adalbero, was Count Palatine of Saxony from 992

- Frederick (d. July 1002 or 15 March 1003), Count in the Harzgau and in the Nordthüringgau, was Count Palatine of Saxony from 995 to 996

- Burchard I (d. after 3 November 1017), the first count of Goseck to hold the title, was a count in the Hassegau from 991, Count Palatine of Saxony from 1003, Count of Merseburg from 1004, and imperial governor from 1012

- Siegfried (•d. 25 April 1038), was Count Palatine of Saxony in 1028

- Frederick I (d. 1042), a younger son of Burchard I, was Count of Goseck and in the Hassegau and was Count Palatine of Saxony in 1040

- William (d. 1062), Count of Weimar, probably Count Palatine of Saxony in 1042

- Dedo (fell in battle in Pöhlde on 5 May 1056), son of Frederick I, Count Palatine of Saxony from 1042 to 1044

- Frederick II (•d. 27 May 1088), younger brother of Dedo, Count Palatine of Saxony in 1056

- Frederick III (murdered near Zscheiplitz on 5 February 1087), son of Frederick II

- Frederick IV (d. 1125 in Dingelstedt am Huy), son of Frederick III, Count Palatine in 1114

- Frederick V (•d. 18 October 1120 or 1121), grandson of Frederick I, Count of Sommerschenburg, Count Palatine of Saxony in 1111

- Frederick VI (•d. 19 May 1162), son of Frederick V, Count of Sommerschenburg, Count Palatine of Saxony from 1123 to 1124

- Herman II (murdered on 30 January 1152), Count of Formbach, Margrave of Meissen from 1124 to 1130 (deposed), Count Palatine of Saxony from 1129 to 1130, married in 1148 to Liutgard of Stade, who had divorced Frederick VI in 1144

- Adalbert (d. 1179), son of Frederick VI, Count Palatine of Sommerschenburg from 1162 until his death

- Louis III (d. 1190), Landgrave of Thuringia from 1172 until his death, appointed Count Palatine of Saxony on the Diet of Gelnhausen on 13 April 1180, abdicated in favour of Herman I in 1181

- Herman III (c. 1155 – 25 April 1215 in Gotha), younger brother of Louis III, Count Palatine of Saxony from 1181 until his death, Landgrave of Thuringia from 1190 until his death

- Louis IV (28 October 1200 – 11 September 1227), son of Herman I, Count Palatine of Saxony and Landgrave of Thuringia from 1217 until his death

- Henry Raspe (1204 – 16 February 1247), son of Herman I, Landgrave of Thuringia from 1227 until his death, Count Palatine of Saxony from 1231 until his death, anti-king of Germany opposing Frederick II and his son Conrad IV from 1246

After Henry Raspe's death, the County Palatine of Saxony and the Landgraviate of Thuringia were given to the House of Wettin, based on a promise made by Emperor Frederick II:

- Henry III (c. 1215 – 15 February 1288), Margrave of Meissen from 1227 until his death, Count Palatine of Saxony and Landgrave of Thuringia from 1247 1265

- Albert II the Degenerate (1240 – 20 November 1314), son of Henry III, Count Palatine of Saxony and Landgrave of Thuringia from 1265 until his death, Margrave of Meissen from 1288 to 1292

- Frederick VII the Bitten (1257 – 16 November 1323), son of Albert II, Count Palatine of Saxony from 1280 to before 1291, Margrave of Meissen before 1291 until his death, Landgrave of Thuringia from 1298 until his death

King Rudolph I of Germany gave the County Palatine of Saxony to the House of Welf:

- Henry I (August 1267 – 7 September 1322), Count Palatine of Saxony from before 1291 until his death, Prince of Brunswick-Grubenhagen from 1291 until his death

- ...

Palatinate of Alamannia / Swabia

.svg.png.webp)

Holy Roman scribes often used the term Swabia interchangeably with Alamannia in the 10th to the 12th centuries.[11]

- Erchanger I, also known as Berchtold I, Count Palatine of Swabia in 880/892

- Erchanger II (•d. 21 January 917), probably a son of Erchanger I, was Count Palatine of Swabia and Missus dominicus and from 915 until his death Duke of Swabia

- [...]

- Frederick I, (c. 1020 – shortly after 1053), Count Palatine of Swabia from 1027 to 1053

- Frederick II (c. 997/999 – c. 1070/1075), father of Frederick I and ancestor of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, Count Palatine of Swabia from 1053 to 1069

- Manegold the Elder (c. 1034/1043 – shortly before summer 1094), son-in-law of Frederick II, Count Palatine of Swabia from 1070 to 1094

- Louis of Staufen, son of Frederick I, Count Palatine of Swabia from 1094 to 1103, founder of St. Faith's Church, Sélestat

- Louis of Westheim, probably a son of his predecessor, Count Palatine of Swabia from 1103 to 1112

- Manegold the Younger, son of Manegold the Elder, Count Palatine of Swabia from 1112 to 1125

- Adalbert of Lauterburg, son of Manegold the Elder, Count Palatine of Swabia from 1125 to 1146

After 1146, the title went to the counts palatine of Tübingen.

Palatinate of Tübingen

- Hugo I (1146–1152)

- Frederick (d. 1162) co-ruler with Hugo II

- Hugo II (1152–1182)

- Rudolf I (1182–1219)

- Hugo III (1185– c. 1228/30) co-ruler with Rudolf I and Rudolf II, went on to found the Montfort-Bregenz lineage

- Rudolf II (d. 1247)

- Hugo IV (d. 1267)

- Eberhard (d. 1304)

- Gottfried I (d. 1316)

- Gottfried II (d. 1369) sold the County Palatine of Tübingen to the Württemberg dynasty, went on to found the Tübingen-Lichteneck lineage

Palatinate of Burgundy

In 1169, Emperor Frederick I created the Free County of Burgundy (not to be confused with its western neighbour, the Duchy of Burgundy). The Counts of Burgundy had the title of Free Count (German: Freigraf), but are sometimes called counts palatine.

Church palatinates

A papal count palatine (Comes palatinus lateranus, properly Comes sacri Lateranensis palatii "Count of the Sacred Palace of Lateran"[12]) began to be conferred by the pope in the 16th century. This title was merely honorary and by the 18th century had come to be conferred so widely as to be nearly without consequence.

The Order of the Golden Spur began to be associated with the inheritable patent of nobility in the form of count palatinate during the Renaissance; Emperor Frederick III named Baldo Bartolini, professor of civil law at the University of Perugia, a count palatinate in 1469, entitled in turn to confer university degrees.[13]

Pope Leo X designated all of the secretaries of the papal curia Comites aulae Lateranensis ("Counts of the Lateran court") in 1514 and bestowed upon them the rights similar to an imperial count palatine. In some cases the title was conferred by specially empowered papal legates. If an imperial count palatine possessed both an imperial and the papal appointment, he bore the title of "Comes palatine imperiali Papali et auctoritate" (Count palatine by Imperial and Papal authority).

The Order of the Golden Spur, linked with the title of count palatine, was widely conferred after the Sack of Rome, 1527, by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor; the text of surviving diplomas conferred hereditary nobility to the recipients.

Among the recipients was Titian (1533), who had painted an equestrian portrait of Charles.[14] Close on the heels of the Emperor's death in 1558, its refounding in papal hands is attributed to Pope Pius IV in 1559.[15] Benedict XIV (In Supremo Militantis Ecclesiæ, 1746) granted to the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre the right to use the title of Count of the Sacred Palace of Lateran.

By the mid-18th century, the Order of the Golden Spur was being so indiscriminately bestowed that Casanova remarked "The Order they call the Golden Spur was so disparaged that people irritated me greatly when they asked me the details of my cross;"[16]

The order was granted to "those in the pontifical government, artists, and others, whom the pope should think deserving of reward. It is likewise given to strangers, no other condition being required, but that of professing the catholic religion."[17]

Imperial circles

As part of the Imperial Reform, six imperial circles were established in 1500; four more were established in 1512. These were regional groupings of most (though not all) of the various states of the empire for the purposes of defense, imperial taxation, supervision of coining, peace-keeping functions, and public security. Each circle had its own parliament, known as a Kreistag ("Circle Diet"), and one or more directors, who coordinated the affairs of the circle. Not all imperial territories were included within the imperial circles, even after 1512; the Lands of the Bohemian Crown were excluded, as were Switzerland, the imperial fiefs in northern Italy, the lands of the Imperial Knights, and certain other small territories like the Lordship of Jever.

Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, 1806

The Palatine territories on the left bank of the Rhine were annexed by Revolutionary France in 1795, mainly becoming part of the Mont-Tonnerre department. The Palatine Elector Maximilian Joseph accepted the loss of these territories after the Treaty of Paris.[18] Those on the right were taken by the Palatine Elector of Baden, after Napoleonic France dissolved the Holy Roman Empire on 26 December 1805 with the Peace of Pressburg as a consequence of the French victory at the Battle of the Three Emperors (2 December); the remaining Wittelsbach territories were united by Maximilian Joseph under the Kingdom of Bavaria.[19]

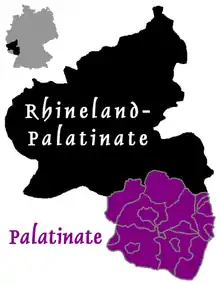

After the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the Palatine nationality came to refer more specifically to the people of the Rhenish Palatinate (German: Rhoipfalz) throughout the 19th century. The Rhenish Palatinate's union with Bavaria was finally dissolved following the reorganisation of German states during the Allied occupation of Germany after World War II. Today the Palatinate occupies roughly the southernmost quarter of the German federal state of Rhineland-Palatinate (Rheinland-Pfalz).

Palatine migrations in the 17th and 18th centuries

Palatinate Campaign, Early Migrations

.jpg.webp)

In the second half of the 17th century, the Palatinate had not yet fully recovered from the destructions of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), in which large parts of the region had lost more than two thirds of its population. The first Palatine migrations began during the Palatinate campaign, which saw heavy fighting in the Palatinate, collapse of the state's economy, and the wholesale slaughter of the region's population, including women, children and non-combattants.[20]

As early as 1632, Catholic Palatines found their way to the Maryland Palatinate, established by the Calvert family (Lords of Baltimore) as a haven for Catholic refugees. The heaviest concentration of Palatines settled in Western Maryland.[21][22][23]

Throughout the Nine Years' War (1688–1697) and the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), recurrent invasions by the French Army devastated the area of what is today Southwest Germany. During the Nine Years War the French had used a scorched-earth policy in the Palatinate.

The depredations of the French Army and the destruction of numerous cities (especially within the Palatinate) created economic hardship for the inhabitants of the region, exacerbated by a rash of harsh winters and poor harvests that created famine in Germany and much of northwest Europe. The specific background of the migration from the Palatinate, as documented in emigrants' petitions for departure registered in the southwest principalities, was impoverishment and lack of economic prospects.[24]

The emigrants came principally from regions comprising present-day Rhineland-Palatinate, Hesse, and northern areas of Baden-Württemberg along the lower Neckar. During the so-called Kleinstaaterei ("small state") period when this emigration occurred, the Middle Rhine region was a patchwork of secular and ecclesiastical principalities, duchies and counties. No more than half of the so-called Palatines originated in the namesake Electoral Palatinate, with others coming from the surrounding imperial states of Palatinate-Zweibrücken and Nassau-Saarbrücken, the Margraviate of Baden, the Hessian Landgraviates of Hesse-Darmstadt, Hesse-Homburg, Hesse-Kassel, the Archbishoprics of Trier and Mainz, and various minor counties of Nassau, Sayn, Solms, Wied, and Isenburg.[25]

The Great Palatine Migration of 1709

What triggered the mass emigration in 1709 of mostly impoverished people to England was the Crown's promise of free land in British America. Parliament discovered in 1711 that several "agents" working on behalf of the Carolina province had promised the peasants around and South of Frankfurt free passage to the plantations. Spurred by the success of several dozen families the year before, thousands of German families headed down the Rhine to England and the New World.[26]

The first boats packed with refugees began arriving in London in early May 1709. The first 900 people to reach England were given housing, food and supplies by a number of wealthy Englishmen.[27] The immigrants were called "Poor Palatines": "poor" in reference to their pitiful and impoverished state upon arrival in England, and "Palatines" since many of them came from lands controlled by the Elector Palatine.

The majority came from regions around the Rhenish Palatinate and, against the wishes of their respective rulers, they fled by the thousands on small boats and ships down the Rhine River to the Dutch city of Rotterdam, whence the majority embarked for London. Throughout the summer, ships unloaded thousands of refugees, and almost immediately their numbers overwhelmed the initial attempts to provide for them. By summer, most of the Poor Palatines were settled in Army tents in the fields of Blackheath and Camberwell. A Committee dedicated to coordinating their settlement and dispersal sought ideas for their employment. This proved difficult, as the Poor Palatines were unlike previous migrant groups—skilled, middle-class, religious exiles such as the Huguenots or the Dutch in the 16th century—but rather were unskilled rural laborers, neither sufficiently educated nor healthy enough for most types of employment.

Political controversy

During the reign of Queen Anne (1702–1714), political polarization increased. Immigration and asylum had long been debated, from coffee-houses to the floor of Parliament, and the Poor Palatines were inevitably brought into the political crossfire.[28]

For the Whigs, who controlled Parliament, these immigrants provided an opportunity to increase Britain's workforce. Only two months before the German influx, Parliament had enacted the Foreign Protestants Naturalization Act 1708, whereby foreign Protestants could pay a small fee to become naturalized. The rationale was the belief that an increased population created more wealth, and that Britain's prosperity could increase with the accommodation of certain foreigners. Britain had already benefited from French Huguenot refugees, as well as the Dutch (or "Flemish") exiles, who helped revolutionize the English textile industry.[29] Similarly, in an effort to increase the sympathy and support for these refugees, many Whig tracts and pamphlets described the Palatines as "refugees of conscience" and victims of Catholic oppression and intolerance. Louis XIV of France had become infamous for the persecution of Protestants within his realm. The invasion and destruction of the Rhineland region by his forces was considered by many in Britain as a sign that the Palatines were likewise objects of his religious tyranny. With royal support, the Whigs formulated a charity brief to raise money for the "Poor Distressed Palatines", who had grown too numerous to be supported by the Crown alone.[30]

The Tories and members of the High Church Party (those who sought greater religious uniformity), were dismayed by the numbers of Poor Palatines amassing in the fields of southeast London. Long-standing opponents of naturalization, the Tories condemned the Whig assertions that the immigrants would be beneficial to the economy, as they were already an acute financial burden. Similarly, many who worried for the security of the Church of England were concerned about the religious affiliations of these German families, especially after it was revealed that many (perhaps more than 2,000) were Catholic.[31] Although the majority of the Catholic Palatines were immediately sent back across the English Channel, many English thought their presence disproved the claimed religious refugee status of the Poor Palatines.

The author Daniel Defoe was a major spokesman, who attacked the critics of the government's policy. Defoe's Review, a tri-weekly journal dealing usually with economic matters, was for two months dedicated to denouncing opponents’ claims that the Palatines were disease-ridden, Catholic bandits who had arrived in England "to eat the Bread out of the Mouths of our People."[32] In addition to dispelling rumors and propounding the benefits of an increased population, Defoe advanced his own ideas of how the Poor Palatines should be "disposed".

Dispersal

Not long after the Palatines' arrival, the Board of Trade was charged with finding a means for their dispersal. Contrary to the desires of the immigrants, who wanted to be transported to British America, most schemes involved settling them within the British Isles, either on uninhabited lands in England or in Ireland (where they could bolster the numbers of the Protestant minority). Most officials involved were reluctant to send the Palatines to America due to the cost, and to the belief that they would be more beneficial if kept in Britain. Since the majority of the Poor Palatines were husbandmen, vinedressers and laborers, the English felt that they would be better suited in agricultural areas. There were some attempts to disperse them in neighboring towns and cities.[33] Ultimately, large-scale settlement plans came to nothing, and the government sent Palatines piecemeal to various regions in England and Ireland. These attempts mostly failed, and many of the Palatines returned from Ireland to London within a few months, in far worse condition than when they had left.[34]

The commissioners finally acquiesced and sent numerous families to New York to produce naval stores at camps along the Hudson River. The Palatines transported to New York in the summer of 1710 totaled about 2800 people in ten ships, the largest group of immigrants to enter British America before the American Revolution. Because of their refugee status and weakened condition, as well as shipboard diseases, they had a high rate of fatalities. They were kept in quarantine on an island in New York harbor until ship's diseases had run their course. Another 300-some Palatines reached Carolina. Despite the ultimate failure of the Naval stores effort and delays on granting them land in settled areas (they were given grants on the frontiers), they had reached the New World and were determined to stay. Their descendants are scattered across the United States and Canada.

The experience with the Poor Palatines discredited the Whig philosophy of naturalization, and figured in political debates as an example of the pernicious effects of offering asylum to refugees. Once the Tories returned to power, they retracted the Act of Naturalization, which they claimed had lured the Palatines to England (though few had in fact become naturalized).[35] Later attempts to reinstate an Act for Naturalization would suffer from the tarnished legacy of Britain's first attempt to support mass immigration of foreign-born peoples.

Re-settlement in Ireland

In 1709, some 3,073 Palatines were transported to Ireland.[36] Some 538 families were settled as agricultural tenants on the estates of Anglo-Irish landlords. However, many of the settlers failed to permanently establish themselves and 352 families were reported to have left their holdings, with many returning to England.[37] By late 1711 only around 1,200 of the Palatines remained in Ireland.[36]

Some contemporary opinion blamed the Palatines for the failure of the settlement. William King, the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin, said, "I conceive their design 'tis but to eat and drink at Her Majesty's cost, live idle and complain against those that maintain them." But the real reason for the failure was apparently lack of political support for the settlement from the High Church Tories, who generally opposed foreign involvement and saw the settlers as potential Dissenters rather than buttresses to their own established church.[36]

The Palatine settlement was successful in two areas: Counties Limerick and Wexford. In Limerick, 150 families were settled in 1712 on the lands of the Southwell family near Rathkeale. Within a short time, they had made a success of farming hemp, flax, and cattle. In Wexford about the same time, a large Palatine population was settled on the lands of Abel Ram, near Gorey. The distinctive Palatine way of life survived in these areas until well into the nineteenth century. Today, names of Palatine origin, such as Switzer, Hick, Ruttle, Sparling, Tesky, Fitzell, and Gleasure are dispersed throughout Ireland.[37]

Palatine migration to New York and Pennsylvania

.jpg.webp)

Palatines had trickled into British America since their earliest days. The first mass migration, however, began in 1708. Queen Anne's government had sympathy for the Palatines and had invited them to go to America and work in trade for passage. Official correspondence in British records shows a combined total of 13,146 refugees traveled down the Rhine and or from Amsterdam to England in the summer of 1709.[38] More than 3,500 of these were returned from England either because they were Roman Catholic or at their own request.[39] Henry Z Jones, Jr. quotes an entry in a churchbook by the Pastor of Dreieichenhain that states a total of 15,313 Palatines left their villages in 1709 "for the so-called New America and, of course, Carolina".[40]

The flood of immigration overwhelmed English resources. It resulted in major disruptions, overcrowding, famine, disease and the death of a thousand or more Palatines. It appeared the entire Palatinate would be emptied before a halt could be called to emigration.[41] Many reasons have been given to explain why so many families left their homes for an unknown land. Knittle summarizes them: "(1) war devastation, (2) heavy taxation, (3) an extraordinarily severe winter, (4) religious quarrels, but not persecutions, (5) land hunger on the part of the elderly and desire for adventure on the part of the young, (6) liberal advertising by colonial proprietors, and finally (7) the benevolent and active cooperation of the British government."[42]

No doubt the biggest impetus was the harsh, cold winter that preceded their departure. Birds froze in mid-air, casks of wine, livestock, and whole vineyards were destroyed by the unremitting cold.[43] With what little was left of their possessions, the refugees made their way on boats down the Rhine to Amsterdam, where they remained until the British government decided what to do about them. Ships were finally dispatched for them across the English Channel, and the Palatines arrived in London, where they waited longer while the British government considered its options. So many arrived that the government created a winter camp for them outside the city walls. A few were settled in England, a few more may have been sent to Jamaica and Nassau, but the greatest numbers were sent to Ireland, Carolina and especially, New York in the summer of 1710. They were obligated to work off their passage.

The Reverend Joshua Kocherthal paved the way in 1709, with a small group of fifty who settled in Newburgh, New York, on the banks of the Hudson River. "In the summer of 1710, a colony numbering 2,227 arrived in New York and were [later] located in five villages on either side of the Hudson, those upon the east side being designated as East Camp, and those upon the west, as West Camp."[44] A census of these villages on 1 May 1711 showed 1194 on the east side and 583 on the west side. The total number of families was 342 and 185, respectively.[45] About 350 Palatines had remained in New York City, and some settled in New Jersey. Others travelled down the Susquehanna River, settling in Berks County, Pennsylvania. The locations of the New Jersey communities correlate with the foundation of the oldest Lutheran churches in that state, i.e., the first called Zion at New Germantown (now Oldwick), Hunterdon County; the 'Straw Church' now called St. James at Greenwich Township, Sussex (now Pohatong Township, Warren County); and St. Paul's at Pluckemin, Bedminster Township, Somerset County.

Indentured servitude

.jpg.webp)

Settlement by Palatines on the east side (East Camp) of the Hudson River was accomplished as a result of Governor Hunter's negotiations with Robert Livingston, who owned Livingston Manor in what is now Columbia County, New York. (This was not the town now known as Livingston Manor on the west side of the Hudson River.) Livingston was anxious to have his lands developed. The Livingstons benefited for many years from the revenues they received as a result of this business venture. West Camp, on the other hand, was located on land the Crown had recently "repossessed" as an "extravagant grant". Pastors from both Lutheran and Reformed churches quickly began to serve the camps and created extensive records of these early settlers and their life passages long before the state of New York was established or kept records.

The British Crown believed that the Palatines could work and be "useful to this kingdom, particularly in the production of naval stores, and as a frontier against the French and their Indians".[46] Naval stores which the British needed were hemp, tar and pitch, poor choices given the climate and the variety of pine trees in New York State. On 6 September 1712, work was halted. "The last day of the government subsistence for most of the Palatines was September 12th."[47] "Within the next five years, many Palatines moved elsewhere. Several went to Pennsylvania, others to New Jersey, settling at Oldwick or Hackensack, still others pushed a few miles south to Rhinebeck, New York, and some returned to New York City, while quite a few established themselves on Livingston Manor [where they had originally been settled]. Some forty or fifty families went to Schoharie between September 12th and October 31, 1712."[48]

In the winter of 1712–13, six Palatines approached the Mohawk clan mothers to ask for permission to settle in the Schoharie River valley, a tributary of the Mohawk River.[49] The clan mothers, moved by the story of their misery and suffering, granted the Palatines permission to settle; in the spring of 1713 about 150 Palatine families moved into the Schoharie valley.[50] The Palatines had not understood that the Haudenosaunee were a matrilineal kinship society, and that the clan mothers had considerable power. They headed the nine clans that made up the Five Nations. The Palatines had expected to meet male sachems rather than these women, but property and descent were passed through the maternal lines.

Resettlement

A report in 1718 placed 224 families of 1,021 persons along the Hudson River while 170 families of 580 persons were in the Schoharie valley.[51] In 1723, under Governor Burnet, 100 heads of families from the work camps were settled on 100 acres (0.40 km2) each in the Burnetsfield Patent midway in the Mohawk River Valley, just west of Little Falls. They were the first Europeans to be allowed to buy land that far west in the valley.

After hearing Palatine accounts of poverty and suffering, the clan mothers granted permission for them to settle in the Schoharie Valley.[49] The women elders had their own motives. During the 17th century, the Haudenosaunee had suffered high mortality from new European infectious diseases, to which they had no immunity. They also had been engaged in warfare against the French and against other indigenous tribes. Finally, in the 1670s–80s French Jesuit missionaries had converted thousands of Iroquois (mostly Mohawk) to Catholicism and persuaded the converts to settle near Montreal.[52]

Historians referred to the Haudenosaunee who moved to New France as the Canadian Iroquois, while those who remained behind are described as the League Iroquois. At the beginning of the 17th century, about 2,000 Mohawk lived in the Mohawk River Valley, but by the beginning of the 18th century, the population had dropped to about 600 people. They were in a weakened position for resisting encroachment by English settlers.[52] The governors of New York had showed a tendency to grant Haudenosaunee land to British settlers without permission. The clan mothers believed that leasing land to the poor Palatines was a preemptive way to block the governors from granting their land to land-hungry immigrants from the British isles.[52] In their turn, the British authorities believed that the Palatines would serve as a protective barrier, providing a reliable militia who would stop French and Indigenous raiders coming down from New France (modern Canada).[53] The Palatine communities gradually extended along both sides of the Mohawk River to Canajoharie. Their legacy was reflected in place names, such as German Flatts and Palatine Bridge, and the few colonial-era churches and other buildings that survived the Revolution. They taught their children German and used the language in churches for nearly 100 years. Many Palatines married only within the German community until the 19th century.

The Palatines settled on the frontiers of New York province in Kanienkeh ("the land of the flint"), the homeland of the Five Nations of the Iroquois League (becoming the Six Nations when the Tuscarora joined the League in 1722) in what is now upstate New York, and formed a very close relationship with the Iroquois. The American historian David L. Preston described the lives of the Palatine community as being "interwoven" with the Iroquois communities.[54] One Palatine leader said about the relationship of his community with the Haudenosauee that: "We intend to live our lifetime together as brothers".[54] The Haudenosauee taught the Palatines about the best places to gather wild edible nuts, together with roots and berries, and how to grow the "Three Sisters", as the Iroquois called their staple foods of beans, squash and corn.[52] One Palatine leader, Johann Conrad Weiser, had his son live with a Mohawk family for a year in order to provide the Palatines with both an interpreter and a friend who might bridge the gap between the two different communities.[52] The Palatines came from the patriarchal society of Europe, whereas the Haudenosaunee had a matrilineal society, in which clan mothers selected the sachems and the chiefs.

The Haudenosaunee admired the work ethic of the Palatines, and often rented their land to the hard-working immigrants.[52] In their turn, the Palatines taught Haudenosaunee women how to use iron plows and hoes to farm the land, together with how to grow oats and wheat.[52] The Haudenosaunee considered farming to be women's work, as their women planted, cultivated and harvested their crops. They considered the Palatine men to be unmanly because they worked the fields. Additionally, the Palatines brought sheep, cows, and pigs to Kanienkeh.[52] With increased agricultural production and money coming in as rent, the Haudenosaunee began to sell the surplus food to merchants in Albany.[52] Many clan mothers and chiefs, who had grown wealthy enough to live at about the same standard of living as a middle-class family in Europe, abandoned their traditional log houses for European-style houses.[52]

In 1756, one Palatine farmer brought 38,000 beads of black wampum during a trip to Schenectady, which was enough to make dozens upon dozens of wampum belts, which were commonly presented to Indigenous leaders as gifts when being introduced.[54] Preston noted that the purchasing of so much wampum reflected the very close relations the Palatines had with the Iroquois.[54] The Palatines used their metal-working skills to repair weapons that belonged to the Iroquois, built mills that ground corn for the Iroquois to sell to merchants in New York and New France, and their churches were used for Christian Iroquois weddings and baptisms.[55] There were also a number of intermarriages between the two communities.[55] Doxstader, a surname common in some of the rural areas of south-western Germany, is also a common Iroquois surname.[55]

Palatine and Indigenous relationship

Preston wrote that the popular stereotype of United States frontier relations between white settler colonists and Native Americans as being from two racial worlds that hardly interacted did not apply to the Palatine-Iroquois relationship, writing that the Palatines lived between Iroquois settlements in Kanienkeh, and the two peoples "communicated, drank, worked, worshipped and traded together, negotiated over land use and borders, and conducted their diplomacy separate from the colonial governments".[56] Some Palatines learned to perform the Haudenosaunee condolence ceremony, where condolences were offered to those whose friends and family had died, which was the most important of all Iroquois rituals.[52] The Canadian historian James Paxton wrote the Palatines and Haudenosaunee "visited each other's homes, conducted small-scale trade and socialized in taverns and trading posts".[52]

Unlike the frontier in Pennsylvania and in the Ohio river valley, where English settlers and the Indians had bloodstained relations, leading to hundreds of murders, relations between the Palatine and Indians in Kanienkeh were friendly. Between 1756 and 1774 in the New York frontier, only 5 colonists or British soldiers were killed by Native Americans, while just 6 Natives were killed by soldiers or settlers.[57] The New York frontier had no equivalent to the Paxton Boys, a vigilante group of Scots-Irish settlers on the Pennsylvania frontier who waged a near-genocidal campaign against the Susquehannock Indians in 1763–64, and the news of the killing perpetrated by the Paxton Boys was received with horror by both whites and Indians on the New York frontier.[57]

However, the Iroquois had initially allowed the Palatines to settle in Kanienkeh out of sympathy for their poverty, and expected them to ultimately contribute for being allowed to live on the land when they become wealthier. In a letter to Sir William Johnson, the Superintendent of Northern Indian Affairs, in 1756, Oneida sachems and clan mothers complained that they had allowed the Palatines to settle in Kanienkeh out of "compassion to their poverty and expected when they could afford it that they would pay us for their land", going on to write now that the Palatines had "grown rich they not only refuse to pay us for our land, but impose on us in everything we have to do with them".[55] Likewise, many Iroquois sachems and clan mothers complained that their young people were too fond of drinking the beer brewed by the Palatines, charging that alcohol was a destructive force in their community.[58]

Palatines during the French and Indian War (1754–1763)

Despite the intentions of the British, the Palatines showed little inclination to fight for the British Crown, and during French and Indian War, tried to maintain neutrality. After the Battle of Fort Bull and the Fall of Fort Oswego to the French, German Flatts and Fort Herkimer become the northern frontier of the British Empire in North America, causing the British Army to rush regiments to the frontier.[59] One Palatine, Hans Josef Herkimer, complained about the British troops in his vicinity in a letter written in broken English to the authorities: "Tieranniece [tyranny] over me they think proper ... Not only Infesting my House and taking my rooms at their pleashure [pleasure] but takes what they think Nesserarie [necessary] of my Effects".[59]

The Palatines sent messages via the Oneida to Quebec City to tell the governor-general of New France, the Marquis de Vaudreuil, of their wish to be neutral while at the same time trading with the French via Indian middlemen.[60] An Oneida Indian passed on a message to Vaudreuil in Quebec City, saying: "We inform you of a message given to us by a Nation that is neither English, nor French nor Indian and inhabits the lands around us ... That Nation has proposed to annex us to itself in order to afford each other mutual help and protection against the English".[53] Vaundreuil in reply stated "I think I know that nation. There is reason to believe they are the Palatines".[53] Another letter sent by the Palatines to Vaudreuil in late 1756 declared that they "looked upon themselves in danger as well as the Six Nations, they are determined to live and die by them & therefore begged the protection of the French".[60]

Vaudreuil informed the Palatines that neutrality was not an option and they could either submit to the King of France or face war.[60] The Palatines tried to stall, causing Vaudreuil to warn them that this "trick will avail nothing; for whenever I think proper, I shall dispatch my warriors to Corlac" (the French name for New York).[53] At one point, the Oneida sent a message to Vaudreuil asking that "not to due [do] them [the Palatines] any hurt as they were no more white people but Oneidas and that their blood was mixed with the Indians".[55] Preston wrote that the letter may have been exaggerating somewhat, but interracial and intercultural sexual relations are known to have occurred on the frontier.[55] The descendants of the Palatine Dutch and Indians were known as Black Dutch.[61]

On 10 November 1757, the Oneida sachem Canaghquiesa warned the Palatines that a force of French and Indigenous combatants were on their way to attack, telling them that their women and children should head for the nearest fort, but Canaghquiesa noted that they "laughed at me and slapping their hands on their Buttucks [buttocks] said they did not value the Enemy".[62] On 12 November 1757, a raiding party of about 200 Mississauga and Canadian Iroquois warriors together with 65 Troupes de la Marine and Canadien militiamen fell on the settlement of German Flatts at about 3:00 am, burning the town down to the ground, killing about 40 Palatines while taking 150 back to New France.[63] One Palatine leader, Johan Jost Petri, writing from his prison in Montreal, complained about how "our people have been taken by the Indians and the French (but for the most part by our own Indians) and by our own fault".[64] Afterwards, a group of Oneida and Tuscaroras came to the ruins of the German Flatts to offer food and shelter for the survivors and to bury the dead.[56] In a letter to Johnson, Canaghquiesa wrote "we have condoled with our Brethren the Germans on the loss of their Friends who have been lately killed and taken by the Enemy ... that Ceremony was over three days ago".[56]

New York Dutch

.jpg.webp)

Because of the concentration of Palatine refugees in New York in the 18th century, the term "Palatine" became associated with German. "Until the American War of Independence 'Palatine' henceforth was used indiscriminately for all 'emigrants of German tongue'."[65]

Pennsylvania Dutch

Many Pennsylvania Dutchmen are descendants of Palatines who settled the Pennsylvania Dutch Country.[6] The Pennsylvania Dutch language, spoken by the Amish and Pennsylvania Dutch in the United States, is derived primarily from the Palatine German language which many Mennonite refugees brought to Pennsylvania in the years 1717 to 1732.[66] The only existing Pennsylvania German newspaper, Hiwwe wie Driwwe, was founded in Germany un 1996 in the village of Ober-Olm, which is located close to Mainz, the state capital (and is published bi-annually as a cooperation project with Kutztown University). In the same village one can find the headquarters of the German-Pennsylvanian Association.

Palatine migration in the 19th century

Many more Palatines from the Rhenish Palatinate emigrated in the course of the 19th century. For a long time in the American Union, "Palatine" meant German American.[67]

Palatine immigrants came to live in big industrial cities such as Germantown, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania. Land-searching Palatines moved to the Midwestern States and founded new homes in the fertile regions of Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio.[68]

A vast inpouring of Palatines began to come especially in the middle of the 19th century.[69] Johann Heinrich Heinz (1811-1891), the father of Henry John Heinz who founded the H. J. Heinz Company in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, emigrated from Kallstadt, Palatinate, to the United States in 1840.

Notable Palatines and descendants

Included are immigrants that came during the Colonial Period between 1708 and 1775 and their immediate family members.

- 1708 – Josua Harrsch alias Kocherthal (1669–1719), Lutheran minister

- 1710 – Johann Conrad Weiser Sr. (1662–1746), baker

- 1710 – Conrad Weiser (1696–1760), interpreter

- 1710 – Johann Hartman Windecker (1676–1754), settler

- 1710 – John Peter Zenger (1697–1746), printer and journalist

- 1710 – Johann Jost Herkimer (1700–1775), father of brigadier general Nicholas Herkimer (c 1728–1777) and of Loyalist Johan Jost Herkimer (c 1732–1795)

- 1717 – Caspar Wistar (1696–1752), glassmaker

- 1720 – Conrad Beissel (1691–1768), Baptist leader

- 1729 – Alexander Mack, (1679–1735), Brethren leader

- 1738 – Casper Shafer (1712–1784), miller

- 1738 – John Reister (1715–1804), farmer

- 1742 – Henry Muhlenberg (1711–1787), Lutheran pastor

- 1746 – John Christopher Hartwick (1714–1796), Lutheran minister

- 1749 – Henry Stauffer (c 1724–1777), settler

- 1750 – Henry William Stiegel (1729–1785), glassmaker

- 1755 – Bodo Otto (1711–1787), surgeon

- 1775 – David Ziegler (1748–1811), officer

See also

Notes

- ↑ Hiroshi Fukurai, Richard Krooth (2021). Original Nation Approaches to Inter-National Law: The Quest for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Nature in the Age of Anthropocene. Springer Nature. p. 111.

- ↑ Matthieu Arnold (2016). John Calvin: The Strasbourg Years (1538-1541). Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 68.

- ↑ Sanford Hoadley Cobb (1897). The Story of the Palatines: An Episode in Colonial History. pp. 24, 26.

- ↑ David Alff (2017). The Wreckage of Intentions: Projects in British Culture, 166-173. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 167.

- ↑ New York (State). Legislature. Senate (1915). Proceedings of the Senate of the State of New York on the Life, Character and Public Service of William Pierson Fiero. p. 7.

- 1 2 "Chapter Two – The History Of The German Immigration To America – The Brobst Chronicles". ancestry.com. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ↑ George Reeser Prowell (1907). History of York County, Pennsylvania. Vol. 1. Cornell University. p. 133.

- ↑ Brockhaus Encyclopedia, Mannheim 2004, paladin

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Holland, Arthur William (1911). "Palatine". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 595–596.

- ↑ David Alff (2017). The Story of the Palatines: An Episode in Colonial History. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 167.

- ↑ The name Alamannia itself came into use from at least the 8th century; in pago Almanniae 762, in pago Alemannorum 797, urbs Constantia in ducatu Alemanniae 797; in ducatu Alemannico, in pago Linzgowe 873. From the 9th century, Alamannia was increasingly used as a reference to the Alsace specifically, and the Alamannic territory in general was increasingly called the Duchy of Swabia. By the 12th century, the name Swabia had mostly replaced Alamannia. S. Hirzel, Forschungen zur Deutschen Landeskunde 6 (1888), p. 299.

- ↑ Rock, P.M.J. (1908) Pontifical Decorations In The Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ↑ "Bartolini also received the Knighthood of the Golden Spur, a title that sometimes accompanied the office of count palatinate in the Renaissance" Grendler 2004:184 note 134.

- ↑ C Hope, "Titian as a Court Painter", Oxford Art Journal, 1979.

- ↑ Thomas Robson, The British Herald; or, Cabinet of armorial bearings of the nobility... (1830) s.v. "Golden Spur, in Rome" and plate 4 (fig. 21) and 5 (figs 3 and 7).

- ↑ "L'ordre qu'on appelle de l'Éperon d'Or était si décrié qu'on m'ennuyait beaucoup quand on demandait des nouvelles de ma croix." (Histoire de ma vie, 8;ix);.

- ↑ Robson 1830.

- ↑ "Die Auflösung der Kurpfalz" [Dissolution of the Electoral Palatinate]. Kurpfalz Regional Archiv. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ↑ Nicholls, David (1999). Napoleon: A Biographical Companion (annotated ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-8743-6957-1.

- ↑ University of California (1907). Commercial and Financial Chronicle Bankers Gazette, Commercial Times, Railway Monitor and Insurance Journal. National News Service. p. 9.

- ↑ Sudie Doggett Wike (2022). German Footprints in America, Four Centuries of Immigration and Cultural Influence. McFarland Incorporated Publishers. p. 155.

- ↑ Clayton Colman Hall (1902). The Lords Baltimore and the Maryland Palatinate, Six Lectures on Maryland Colonial History Delivered Before the Johns Hopkins University in the Year 1902. J. Murphy Company. p. 55.

- ↑ David W. Guth (2017). Bridging the Chesapeake, A ‘Fool Idea’ That Unified Maryland. Archway Publishing. p. 426.

- ↑ Otterness, Philip (2004). Becoming German: The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 23–24. ISBN 9780801473449.

- ↑ Otterness, Philip (2004). Becoming German: The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 9. ISBN 9780801473449.

- ↑ Statt, Daniel. Foreigners and Englishmen: The Controversy over Immigration and Population, 1660-1760. Newark (DE): University of Delaware Press, 1995. pp. 122-130

- ↑ "A Representation of what Several private Gentlemen have done towards the Relief of the poor Palatines", 4 June 1709, National Archives, SP 34/ 10/129 (236A)

- ↑ For an in-depth examination of this debate, see H.T. Dickinson, "Poor Palatines and the Parties", The English Historical Review, Vol. 82, No. 324. (July, 1967).

- ↑ Vigne, Randolph; Littleton, Charles (ed). From Strangers to Citizens : The Integration of Immigrant Communities in Britain, Ireland and Colonial America, 1550-1750, 2001.

- ↑ "Brief for the Relief, Subsistence and Settlement of the Poor Distressed Palatines", 1709.

- ↑ H.T. Dickinson, "Poor Palatines and the Parties", p. 472.

- ↑ Daniel Defoe, The Review, June 21 – August 22, 1709.

- ↑ H.T. Dickinson, ‘Poor Palatines and the Parties’, pp. 475-477.

- ↑ Journals of the House of Commons XVI, p. 596.

- ↑ Statt, Foreigners, pp. 127-129, 167-168.

- 1 2 3 Connolly, S.J. (1992). Religion, Law and Power: The Making of Protestant Ireland 1660-1760. p. 302. ISBN 0-1982-0587-2.

- 1 2 "The Palatines". Irish Ancestors. Irish Times. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ↑ Knittle, Walter Allen, Early Eighteenth Century Palatine Emigration, Genealogical Publishing, 2019 reprint, p. 65

- ↑ Knittle (2019), Emigration, p. 66

- ↑ Jones, Henry Z, Jr. The Palatine Families of New York 1710, Universal City, California, 1985, p. viii

- ↑ Knittle, Emigration, p. 65

- ↑ Knittle (2019), Emigration, p. 31

- ↑ Knittle (2019), Emigration, p.4

- ↑ Smith, James H., History of Dutchess County, New York, Interlaken, New York: Heart of the Lakes Publishing, p. 57

- ↑ Documentary History of New York, III, 668.

- ↑ Knittle (2019), p. 38

- ↑ Public Record Office, London, C. O. 5/1085, p. 67

- ↑ Knittle (2019), pp. 189–191

- 1 2 Paxton, James Joseph Brant and His World, Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 2008 page 12

- ↑ Paxton (2008), Joseph Brant and His world, pp. 12–13

- ↑ Paxton (2008), Ibid. p. 195

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Paxton, James, Joseph Brant and his world, Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 2008, p. 13

- 1 2 3 4 Preston, David. "'We intend to live our lifetime together as brothers': Palatine and Iroquois Communities in the Mohawk Valley". New York History, Volume 89, No. 2, Spring 2008, p. 183.

- 1 2 3 4 Preston, David. "'We intend to live our lifetime together as brothers': Palatine and Iroquois Communities in the Mohawk Valley". pages 179–189 in New York History, Volume 89, No. 2, Spring 2008, p. 181.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Preston, David. "'We intend to live our lifetime together as brothers': Palatine and Iroquois Communities in the Mohawk Valley". pages 179–189 in New York History, Volume 89, No. 2, Spring 2008, p. 185.

- 1 2 3 Preston, David. "'We intend to live our lifetime together as brothers': Palatine and Iroquois Communities in the Mohawk Valley". pages 179–189 in New York History, Volume 89, No. 2, Spring 2008, p. 188.

- 1 2 Preston, David. The Texture of Contact: European and Indian Settler Communities on the Frontiers of Iroquoia, 1667–1783. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009. p. 180.

- ↑ Paxton, James. Joseph Brant and his world. Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 2008. p. 14.

- 1 2 Preston, David. "'We intend to live our lifetime together as brothers': Palatine and Iroquois Communities in the Mohawk Valley". pages 179–189 in New York History, Volume 89, No. 2, Spring 2008. p. 182.

- 1 2 3 Preston, David. "'We intend to live our lifetime together as brothers': Palatine and Iroquois Communities in the Mohawk Valley". pages 179–189 in New York History, Volume 89, No. 2, Spring 2008. pp. 182–183.

- ↑ Donald N. Yates (2014). Old World Roots of the Cherokee: How DNA, Ancient Alphabets and Religion Explain the Origins of America's Largest Indian Nation. United States of America: Mcfarland. p. 14.

- ↑ Preston, David. "'We intend to live our lifetime together as brothers': Palatine and Iroquois Communities in the Mohawk Valley". pages 179–189 in New York History, Volume 89, No. 2, Spring 2008. pp. 186–187.

- ↑ Preston, David. "'We intend to live our lifetime together as brothers': Palatine and Iroquois Communities in the Mohawk Valley". pages 179–189 in New York History, Volume 89, No. 2, Spring 2008. p. 179.

- ↑ Preston, David. "'We intend to live our lifetime together as brothers': Palatine and Iroquois Communities in the Mohawk Valley". pages 179–189 in New York History, Volume 89, No. 2, Spring 2008. pp. 187.

- ↑ Roland Paul and Karl Scherer, Pfalzer in Amerika, Kaiserslautern: Institute for Palatine History and Folklore, 1995, p. 48

- ↑ Astrid von Schlachta: Gefahr oder Segen? Die Täufer in der politischen Kommunikation. Göttingen 2009, p. 427.

- ↑ Jodie Scales (2001). Of Kindred Germanic Origins: Myths, Legends, Genealogy and History of an Ordinary American Family. iUniverse. p. 46.

- ↑ Roland Paul, Karl Scherer (1983). 300 Jahre Pfälzer in Amerika. Pfälzische Verlagsanstalt. p. 93.

- ↑ Nelson Greene (1925). History of the Mohawk Valley, Gateway to the West, 1614-1925: Covering the Six Counties of Schenectady, Schoharie, Montgomery, Fulton, Herkimer, and Oneida, Volume 1. S. J. Clarke. p. 456.

Further reading

- Defoe, Daniel. Defoe's Review. Reproduced from the original edition, with an introduction and bibliographical notes by Arthur Wellesley Secor•d. 9 vols. in 22 (Facsimile Text Soc., 44). New York, 1938–1939.

- Dickinson, Harry Thomas. "The poor Palatines and the parties". English Historical Review, 82 (1967), 464–485.

- Heald, Carolyn A. (2009). The Irish Palatines In Ontario: Religion, Ethnicity, and Rural Migration (2nd ed.). Milton, Ontario: Global Heritage Press. ISBN 978-1-8974-4637-9. OCLC 430037634.

- Jones, Henry Z, Jr. The Palatine Families of Ireland. 2nd. ed., Picton Press: Rockport, Maine, 1990.

- Knittle, Walter Allen. Early eighteenth century Palatine emigration; a British government redemptioner project to manufacture naval stores, by Walter Allen Knittle.. Early Eighteenth Century Palatine Emigration: A British Government Redemptioner Project to Manufacture Naval Stores]. Philadelphia: Dorrance, 1937.

- Statt, Daniel. Foreigners and Englishmen: The Controversy over Immigration and Population, 1660-1760. Newark, Del.: University of Delaware Press, 1995.

- O'Connor, Patrick J. (1989). People Make Places: The Story of the Irish Palatines. Newcastle West, Ireland: Oireacht na Mumhan Books. ISBN 978-0-9512-1841-9.

- Olson, Alison. "The English Reception of the Huguenots, Palatines and Salzburgers, 1680-1734: A Comparative Analysis" in Randolph Vigne & Charles Littleton, (eds.), From Strangers to Citizens: The Integration of Immigrant Communities in Britain, Ireland and Colonial America, 1550-1750. Brighton and Portland, Ore.: The Huguenot Society of Great Britain and Ireland and Sussex Academic Press, 2001.

- O'Reilly, William. "Strangers Come to Devour the Land: Changing Views of Foreign Migrants in Early Eighteenth-Century England". Journal of Early Modern History, (2016), 1-35.

- Otterness, Philip (2007). Becoming German: The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-7117-9. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctt5hh0sn.

- Richter, Conrad. The Free Man. Fictional account of a Palatine who emigrated to the United States in the early 1700s and lived during the Revolutionary War.

.jpg.webp)