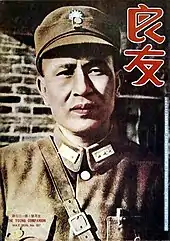

Bai Chongxi | |

|---|---|

| 白崇禧 | |

| |

| 1st Minister of National Defense of the Republic of China | |

| In office 23 May 1946 – 2 June 1948 | |

| Preceded by | Chen Cheng as Minister of War |

| Succeeded by | He Yingqin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 March 1893 Guilin, Guangxi, Qing Empire |

| Died | 2 December 1966 (aged 73) Taipei, Taiwan |

| Political party | Kuomintang |

| Spouse | Ma P'ei-chang |

| Children | 10, including Kenneth |

| Alma mater | Guangxi Military Cadre Training School Baoding Military Academy |

| Awards | Order of Blue Sky and White Sun Legion of Merit |

| Nickname(s) | The Wise Man, Little Zhuge |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | New Army National Revolutionary Army |

| Years of service | 1907–1949 |

| Rank | General |

| Unit | New Guangxi Clique |

| Commands | Minister Of National Defense, Central China Pacification Director |

| Battles/wars | |

Bai Chongxi (18 March 1893 – 2 December 1966; Chinese: 白崇禧; pinyin: Bái Chóngxī; Wade–Giles: Pai Ch'ung-hsi, IPA: [pɑ́ɪ̯ t͡ʂʰʊ́ŋɕǐ], Xiao'erjing: ﺑَﻰْ ﭼْﻮ ثِ) was a Chinese general in the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China (ROC) and a prominent Chinese Nationalist leader.[1] He was of Hui ethnicity and of the Muslim faith. From the mid-1920s to 1949, Bai and his close ally Li Zongren ruled Guangxi province as regional warlords with their own troops and considerable political autonomy. His relationship with Chiang Kai-shek was at various times antagonistic and cooperative. He and Li Zongren supported the anti-Chiang warlord alliance in the Central Plains War in 1930, then supported Chiang in the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War. Bai was the first defense minister of the Republic of China from 1946 to 1948. After losing to the Communists in 1949, he fled to Taiwan, where he died in 1966.

Warlord era

Bai was born in Guilin, Guangxi and given the courtesy name Jiansheng (健生). He was a descendant of a Persian merchant of the name Baiderluden, whose descendants adopted the Chinese surname Bai. His Muslim name was Omar Bai Chongxi.[2]

He was the second of three sons. His family was said to have come from Sichuan. At the age of 14 he attended the Guangxi Military Cadre Training School in Guilin, a modern-style school run by Cai E to modernize Guangxi's military. Bai and classmates Huang Shaohong and Li Zongren would become the three leading figures of Guangxi's military. For a time Bai withdrew from the military school at the request of his family and studied at the civilian Guangxi Schools of Law and Political Science.

With the outbreak of the Xinhai Revolution in 1911, under the leadership of Huang Shaoxiong, Bai joined a Students Dare to Die corps. After entering the Nanjing Enlistment Corps he transferred from the Corps to the Second Military Preparatory School at Wuchang. He graduated from the school in 1914, then underwent pre-cadet training for six months before attending the third class of Baoding Military Academy in June 1915. He became a 1st Guangxi Division probationary officer upon returning to Guangxi.[3]

Bai rose to fame during the warlord era by allying with Huang Shaohong (a fellow deputy commander of the Model Battalion of the Guangxi First Division) and Li Zongren as supporters of Kuomintang leader Sun Yat-sen. This alliance, called the New Guangxi Clique, proceeded to move against Guangxi warlord Lu Rongting in 1924. The coalition's efforts brought Guangxi Province under ROC jurisdiction, and Pai and Li represented a new generation of Guangxi leaders.

The Nationalist chief of staff (acting) was Bai.[4] The 13th Army had him as the commander.[5] The Nationalist Northern Punitive Expedition was participated in by Bai.[5]

During the Northern Expedition (1926–28) Bai was the Chief of Staff of the National Revolutionary Army and credited with many victories over the northern warlords, often using speed, maneuver and surprise to defeat larger enemy forces. He led the Eastern Route Army that conquered Hangzhou and Shanghai in 1927. As garrison commander of Shanghai, he also took part in the purge of Communist elements of the National Revolutionary Army on April 4, 1927, and of the labor unions in Shanghai. Bai also commanded the forward units that first entered Beijing and was credited with being the senior commander on site to complete the Northern Expedition. For many of his battlefield exploits during the Northern expedition, he was given the laudatory nickname Xiao Zhuge, literally "Zhuge Liang Jr.", of the Three Kingdoms fame. Bai was the commander of Kuomintang forces in the Shanghai massacre of 1927, where he directed the KMT purge of Communists in the party.

In 1928, during the Northern Expedition, Bai led Kuomintang forces in the defeat and destruction of Fengtian Clique Gen. Zhang Zongchang, capturing 20,000 of his 50,000 troops and almost capturing Zhang himself, who escaped to Manchuria.[6]

Bai personally had around 2,000 Muslims under his control during his stay in Beijing in 1928 after the Northern Expedition was completed; it was reported by Time magazine that they "swaggered riotously" in the aftermath[7] In June 1928 in Beijing, Bai Chongxi announced that the forces of the Kuomintang would seize control of Manchuria and the enemies of the Kuomintang would "scatter like dead leaves before the rising wind".

Bai was out of money and bankrupt in December 1928. He planned to lead 60,000 troops from east China to Xinjiang province and construct a railroad as a barrier against Russian encroachment in Xinjiang. His plan was perceived by some to be against Feng Yuxiang.[8] The Military Council refused to authorize him leaving Peiping to go to Hankow.[9]

At the end of the Northern Expedition, Chiang Kai-shek began to agitate to get rid of the Guangxi forces. At one time in 1929 Bai had to escape to Vietnam to avoid harm. Hubei and Guangxi were subjected to the Hankou subcouncil of Li Zongren and Bai Chongxi.[10] Li and Bai's Hankou and Canton self-ruling governments were terminated by Chiang.[11] Hankou was captured by Chiang during the dispute between the Guangxi faction and Nanjing.[12][13] From 1930 to 1936, Bai was instrumental in the Reconstruction of Guangxi, which became a "model" province with a progressive administration. Guangxi supplied over 900,000 soldiers to the war effort against Japan.

During the Chinese Civil War Bai fought against the Communists. In the Long March he allowed the Communists to slip through Guangxi.[14]

Governing his province aptly and capably were two of the things Bai was renowned for in China.[15]

Prominent Muslims like Generals Ma Liang, Ma Fuxiang and Bai Chongxi met in 1931 in Nanjing to discuss intercommunal tolerance between Hui and Han.[16]

Second Sino-Japanese War

The 4th Army Groups chief of staff was Bai Chongxi.[17][18]

An anti-Japanese war was called for by Bai Chongxi, Li Zongren and Chen Jitang in 1936.[19] The menace posed by Japan was seen by Bai Chongxi and Li Zongren.[20]

Formal hostilities broke out on 7 July 1937 between China and Japan with the Marco Polo Bridge Incident outside Beijing. On 4 August 1937 Bai rejoined the Central Government at the invitation of Chiang Kai-shek. During the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45), he was the Deputy Chief of the General Staff responsible for operations and training. He was the key strategist who convinced Chiang to adopt a "Total War" strategy in which China would trade space for time, adopt guerrilla tactics behind enemy lines and disrupt enemy supply lines at every opportunity. When the better armed and trained Japanese troops advanced, the Chinese would adopt a scorched earth campaign in the enemy's path to deny them local supply. Bai was also involved in many key campaigns including the first major victory at the Battle of Tai'erzhuang in Shandong Province in the spring of 1938 when he teamed up with Gen. Li Zongren to defeat a superior enemy. China managed to check and delay the Japanese advance for several months. Subsequently, Bai was appointed Commander of the Field Executive Office of the Military Council in Guilin, with responsibility for the 3rd, 4th, 7th and 9th War Zones. In that capacity he oversaw the successful defense of Changsha, capital of Hunan Province. Between 1939 and 1942, the Japanese attacked Changsha three times and were repelled each time. Bai also directed the Battle of South Guangxi and Battle of Kunlun Pass to retake South Guangxi. The 64th Army and 46th Army were requested to be outfitted by Bai via Gen. Lindsey.[21]

Bai's Guangxi soldiers were praised as a "crack" (as in elite) army during the war against Japan, and he was known to be an able general who could lead the Chinese resistance should Chiang Kai-shek be assassinated.[22] The majority of Chinese presumed that Chiang Kai-shek, as leader of China, tapped Bai to inherit his position.[23] Bai Chongxi led the competent Guangxi Army against the Japanese.[24][25]

In refusing to obey commands from Chiang if he assumed them to be wrong and flawed, Bai Chongxi was alone among fellow military men.[26]

Jihad was declared obligatory and a religious duty for all Chinese Muslims against Japan after 1937 during the Second Sino-Japanese War.[27] Bai also sheltered the Muslim Yuehua publication in Guilin, which printed quotes from the Quran and Hadith justifying the need for Chiang Kai-shek as leader of China.[28] Also, promoted Chinese nationalism and uniting Hui to the Han during the war against Japan.[29]

During the war, Bai traveled throughout the Muslim northwestern provinces of China controlled by the Ma Clique and met with Ma Clique generals to defeat Japanese propaganda.[30][31][32] The Hui Muslim Xidaotang sect pledged allegiance to the Kuomintang after their rise to power and Bai Chongxi acquainted Chiang Kai-shek with the Xidaotang jiaozhu Ma Mingren in 1941 in Chongqing.[33]

Bai Chongxi headed the Chinese Islamic National Salvation Federation.[34][35] In January 1945, he was awarded the Legion of Merit of the United States.[36]

Chinese Civil War

Following the surrender of Japan in 1945, the Chinese Civil War resumed in full-fledged fighting. In the spring of 1946 the Chinese Communists were active in Manchuria. A crack People's Liberation Army unit of 100,000 strong under the Communist Gen. Lin Biao occupied a key railroad junction at Siping. Kuomintang forces could not dislodge them after several attempts; Chiang Kai-shek then sent Bai to oversee the operation. After some redeployment, Nationalist forces were able to decisively defeat Lin's forces after a two-day pitched battle. This was to be the first major victory for the Kuomintang in the 1946-49 stage of the civil war before the fall of mainland China to the Chinese Communists.

In June 1946 Bai was appointed Minister of National Defense.[37] It turned to be a post without power, as Chiang began to bypass Bai on major decisions regarding the Chinese Civil War. Chiang would hold daily briefings in his residence without inviting Bai and began to direct front-line troops personally down to the division level, bypassing the chain of command. The Civil War went poorly for the Kuomintang as Chiang's strategy of holding onto provincial capitals and leaving the countryside to the Communists very quickly caused the downfall of his forces, which had a 4:1 numerical superiority at the beginning of the conflict.

During the Ili Rebellion Bai was considered by the government for the post of Governor of Xinjiang. The position later was given to Masud Sabri, a pro-Kuomintang Uyghur leader.

In April 1948 the first National Assembly in China convened in Nanjing, with thousands of delegates from all over China representing different provinces and ethnic groups. Bai Chongxi, acting as Minister of National Defense, debriefed the Assembly on the military situation, completely ignoring Northern China and Manchuria in his report. Delegates from Manchuria in the assembly responded by yelling out and calling for the death of those responsible for the loss of Manchuria.[38]

In November 1948 Bai, in command of forces in Hankou, met with Generals Fu Zuoyi, Zhang Zhizhong and Chiang Kai-shek in Nanjing about defending Suzhou, the gateway to the Yangzi River valley.[39]

Bai told the Central Political Council of the Kuomintang that negotiating with the Communists would only make them more powerful.[40] Governor of Hunan Cheng Qian, and Bai reached a consensus that they should impede the advance of the Communists by negotiating with them.[41]

In January 1949, with the Communists close to victory, almost everyone in the Nationalist media, political and military command began to demand peace as a slogan and turn against Chiang. Bai Chongxi decided to follow suit with the mainstream current and defied Chiang Kai-shek's orders, refusing to battle Communists near the Huai River and demanding that his soldiers, which were "lent", be sent back to him so he could secure his hold n the province of Guangxi and ignore the central government in Nanjing. Bai was the commander of four armies in Central China in the Hankou region. He demanded that the government negotiate with the Communists like the others.[42] Bai was in charge of the defense of the capital, Nanjing. He sent a telegram requesting that Chiang Kai-shek step down as president, amid a storm of requests by other Kuomintang military and political figures for Chiang to step down and allow a peace deal with the Communists.[43]

When Communist Gen. Lin Biao mounted an attack on Bai Chongxi's forces in Hankow, they retreated quickly, leaving the "rice bowl" of China open for the Communists.[44] Bai retreated to headquarters at Hengyang via a railroad from Hankow to Canton. The railroad then provided access to Guilin where his home was.[45] In August at Hengyang, Bai Chongxi reorganized his troops.[46] In October, as the Canton fell to the Communists, who were almost in complete control of China, Bai Chongxi still commanded 200,000 of his elite troops, making a return to Guangxi for a final stand after covering for Canton.[47]

Taiwan

The riots following the February 28 Incident of 28 February 1947 that broke out in Taiwan due to poor governance by the central government appointed officials and the garrison forces caused many casualties of both native Taiwanese and mainland residents. Bai was sent as Chiang Kai-shek's personal representative on a fact finding mission and to help pacify the populace. After a two-week tour, including interviews with various segments of the Taiwan population, Bai made sweeping recommendations, including replacement of the governor, and prosecution of his chief of secret police. He also granted amnesty to student violators of peace on the condition that their parents take custody and guarantee subsequent proper behavior. For his forthright actions, native Taiwanese held him in high regard.[48]

Bai had another falling out with Chiang when he supported General Li Zongren, his fellow Guangxi comrade-in-arms, for the vice presidency in the 1948 general election when Li won against Chiang's hand picked candidate, Sun Fo. Chiang then removed Bai from the Defense Minister post and assigned him the responsibility for Central and South China. Bai's forces were the last ones to leave the mainland for Hainan Island and eventually to Taiwan.

He served Chief of the General Staff since 1927 until his retirement in 1949.[2] After he came to Taiwan, he was the appointed vice director of the strategic advisory commission in the presidential office.[49][50] He also continued to serve in the Central Executive Committee of the Kuomintang. He reorganized the party from 1950 to 1952.[51]

After the Communist victory, some of Bai Chongxi's Guangxi troops fled to French Indochina where they were detained.[52] Others went to Hainan in retreat.[53]

In 1951, Bai Chongxi made a speech to the entire Muslim world calling for a war against the Soviet Union, claiming that the "imperialist ogre" leader Joseph Stalin was engineering World War III, and Bai also called upon Muslims to avoid the Indian leader Jawaharlal Nehru, accusing him of being blind to Soviet imperialism.[54][55]

He and Chiang never reconciled and he lived in semi-retirement until he died of coronary thrombosis on 2 December 1966 at the age of 73.[56][57] Bai was then given a military funeral by the government, with a Kuomintang Blue Sky with a White Sun flag over his coffin.[58] Bai was buried in the Muslim section of the Liuzhangli (六張犁) Cemetery in Taipei, Taiwan.[59]

Personal life

As a Muslim, he was Chairman of the Chinese Islamic National Salvation Federation, and then the Chinese Muslim Association.[60] Bai Chongxi was a board member of the All-China Inter-religious Association, representing Islam, the other members of the board were a Catholic bishop, Methodist bishop, and the Buddhist abbot Taixu.[61]

Bai sent his son Pai Hsien-yung to Catholic schools in Hong Kong.[62]

During the Northern Expedition, in 1926 in Guangxi, Bai Chongxi led his troops in destroying Buddhist temples and smashing idols, turning the temples into schools and Kuomintang party headquarters.[63] It was reported that almost all of Buddhist monasteries in Guangxi were destroyed by Bai in this manner. The monks were removed.[64] Bai led a wave of anti-foreignism in Guangxi, attacking American, European, and other foreigners and missionaries, and generally making the province unsafe for foreigners. Westerners fled from the province, and some Chinese Christians were also attacked as imperialist agents.[65]

The three goals of his movement were anti-foreignism, anti-imperialism, and anti-religion. Bai led the anti-religious movement, against superstition. Huang Shaoxiong, also a Kuomintang member of the New Guangxi Clique, supported Bai's campaign, and Huang was a non-Muslim, the anti religious campaign was agreed upon by all Guangxi Kuomintang members, so it may have not had anything to do with Bai's beliefs.[66]

As a Kuomintang member, Bai and the other Guangxi clique members allowed the Communists to continue attacking foreigners and idols, since they shared the goal of expelling the foreign powers from China, but they stopped Communists from initiating social change.[67]

British diplomats reported that he also drank wine and ate pork.[68][69]

Bai Chongxi was interested in Xinjiang, a predominately Muslim province. He wanted to resettle disbanded Chinese soldiers there to prevent it from being seized by the Soviet Union.[70] Bai personally wanted to lead an expedition to seize back Xinjiang to bring it under Chinese control, in the style that Zuo Zongtang led during the Dungan revolt.[70] Bai's partner in the Guangxi clique Huang Shaohong planned an invasion of Xinjiang. During the Kumul Rebellion Chiang Kai-shek was ready to send Huang Shaohong and his expeditionary force which he assembled to assist Muslim General Ma Zhongying against Sheng Shicai, but when Chiang heard about the Soviet Invasion of Xinjiang, he decided to withdraw to avoid an international incident if his troops directly engaged the Soviets, leaving Ma alone with not reinforcements to fight the Red Army. Huang was suspicious of this, suspecting that Chiang feared that the Guangxi clique was take control of Xinjiang rather than Chiang's Nanjing regime.[71]

Impact

Bai's reputation as a military strategist was well known.[72] Evans Carlson, a United States Marine Corps colonel, noted that Bai "was considered by many to be the keenest of Chinese military men." Edgar Snow went even further, calling him "one of the most intelligent and efficient commanders boasted by any army in the world."

Bai is the father of Kenneth Hsien-yung Pai, Chinese author and playwright now living in the United States. Bai and his wife had ten children, three girls and seven boys.[73] Their names are Patsy, Diana, Daniel, Richard, Alfred, Amy, David, Kenneth, Robert and Charlie. He married his wife Ma P'ei-chang in 1925.[51]

Of his ten children, three are still living, scattered across America and Taiwan. Taipei Mayor Hau Lung-pin announced in March 2013 that Bai's tomb will form the basis for a Muslim cultural area and Taiwan historical park.[74]

Bai's maternal grandson Muhammad Ma is a Halal butcher, and travels across Taiwan working to preserve the Taiwanese Islamic Community. He also helps foreign migrants with any legal issues they may face in Taiwan.[75]

See also

References

- ↑ Listed General, City of Sydney Library, accessed July 2009

- 1 2 M. Rafiq Khan (1963). Islam in China. Delhi: National Academy. p. 17.

- ↑ Howard L. Boorman; Richard C. Howard; Joseph K.H. Cheng (1979). Biographical dictionary of Republican China, Volume 3. New York City: Columbia University Press. pp. 51–56. ISBN 0-231-08957-0.

- ↑ Current Biography Yearbook. H. W. Wilson Company. 1942. p. 516.

- 1 2 Maxine Block; E. Mary Trow (1 January 1942). Current Biography: Who's News and Why, 1942. Hw Wilson Company. p. 516. ISBN 978-0-8242-0479-2.

- ↑ "China: Potent Hero". Time. September 24, 1928. Archived from the original on September 23, 2009. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ "China: Prattling". Time. September 3, 1928. Archived from the original on November 21, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Bankrupt Pei Stuns China by Ambitions; Hopes to March 60,000 Unpaid Troops 1,000 Miles and Colonize Sinkiang. Railway Line Planned Scheme Is to Erect Bulwark Against Russia--Project Is Viewed as Blow at Feng". The New York Times. 12 December 1928. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ↑ The China Monthly Review. Millard Publishing Company, Incorporated. 1928. p. 31.

- ↑ Emily Hahn (13 October 2015). Chiang Kai-Shek: An Unauthorized Biography. Open Road Media. ISBN 978-1-5040-1627-8.

- ↑ Emily Hahn (28 July 2015). China Only Yesterday: 1850–1950: A Century of Change. Open Road Media. pp. 362–. ISBN 978-1-5040-1628-5.

- ↑ Emily Hahn (1 April 2014). The Soong Sisters. Open Road Media. ISBN 978-1-4976-1953-1.

- ↑ Emily Hahn (1943). The Song Sisters. p. 152.

- ↑ John Gunther (1942). Inside Asia. Harper & Brothers. p. 281. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- ↑ Church Historical Society (U.S.) (1981). Walter Herbert Stowe; Lawrence L. Brown (eds.). "Unknown". Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church. Vol. 50. Church Historical Society. p. 183. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- ↑ Contemporary Japan: A Review of Japanese Affairs. Foreign affairs association of Japan. 1942. p. 1626.

- ↑ The China Monthly Review. J.W. Powell. 1935. p. 214.

- ↑ China Monthly Review. Millard Publishing Company, Incorporated. 1935. p. 214.

- ↑ Emily Hahn (1955). Chiang Kai-shek: An Unauthorized Biography. Doubleday. p. 192. ISBN 9780598859235.

- ↑ Emily Hahn (1955). Chiang Kai-shek: An Unauthorized Biography. Doubleday. p. 228. ISBN 9780598859235.

- ↑ China-Burma-India Theater: Stilwell's Command Problems. Government Printing Office. 1956. pp. 401–. ISBN 978-0-16-088233-3.

- ↑ "Background For War: Asia - Chiang's War". Time. Jun 26, 1939. Archived from the original on November 6, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ John Gunther (1942). Inside Asia. Harper & Brothers. p. 281. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- ↑ Far Eastern Affairs and The American Spokesman. 1939. p. 41.

- ↑ Isoshi Asahi (1939). The Economic Strength of Japan. Tokyo. p. 2.

- ↑ Maxine Block; E. Mary Trow (1942). Current Biography: Who's News and Why, 1942 (reprint ed.). Hw Wilson Co. p. 518. ISBN 0-8242-0479-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Stéphane A. Dudoignon; Hisao Komatsu; Yasushi Kosugi (2006). Intellectuals in the modern Islamic world: transmission, transformation, communication. Taylor & Francis. pp. 135, 336. ISBN 978-0-415-36835-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Stéphane A. Dudoignon; Hisao Komatsu; Yasushi Kosugi (2006). Intellectuals in the modern Islamic world: transmission, transformation, communication. Taylor & Francis. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-415-36835-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Stéphane A. Dudoignon; Hisao Komatsu; Yasushi Kosugi (2006). Intellectuals in the modern Islamic world: transmission, transformation, communication. Taylor & Francis. p. 336 of 352. ISBN 978-0-415-36835-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ John Gunther (1942). Inside Asia. Harper & Brothers. p. 280. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ John Gunther (2007). Inside Asia - 1942 War Edition. READ BOOKS. p. 280. ISBN 978-1-4067-1532-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Maxine Block; E. Mary Trow (1942). Current Biography: Who's News and Why, 1942 (reprint ed.). Hw Wilson Co. p. 518. ISBN 0-8242-0479-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Jonathan Neaman Lipman (1 July 1998). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. University of Washington Press. pp. 197–. ISBN 978-0-295-80055-4.

- ↑ China Magazine. 1942. p. 68.

- ↑ China at War. China Information Publishing Company. 1942. p. 68.

- ↑ "Hoover Acquires The Personal Papers Of General Bai Chongxi, A Prominent Military Leader In Republican China". Hoover Institution. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

- ↑ "Biography of General 1st Rank Bai Chongxi - (白崇禧) - (Pai Chung-hsi) (1893 – 1966), China". Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ↑ "China: Sorrow for Old Chiang". Time. April 26, 1948. Archived from the original on February 1, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ "China: If the Heart Is Pierced". Time. November 15, 1948. Archived from the original on July 5, 2009. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ The China monthly review, Volume 109. J.W. Powell. 1948. p. 56. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Brian Crozier; Eric Chou (1976). The man who lost China: the first full biography of Chiang Kai-shek. Scribner. p. 322. ISBN 0-684-14686-X. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ "China: When Headlines Cry Peace". Time. January 17, 1949. Archived from the original on January 31, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Foreign News: Sugar-Coated Poison". Time. Jan 10, 1949. Archived from the original on January 31, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ "China: The Weary Wait". Time. May 23, 1949. Archived from the original on January 31, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ "China: Defend the Graveyard". Time. May 30, 1949. Archived from the original on January 31, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ "China: A Matter of Despair". Time. Aug 15, 1949. Archived from the original on December 20, 2008. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ "China: Next: Chungking". Time. Oct 24, 1949. Archived from the original on January 31, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ "China: Snow Red & Moon Angel". Time. Apr 7, 1947. Archived from the original on November 2, 2007. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ Ku Kim; Jongsoo Lee (2000). The autobiography of Kim Ku, Volume 20. University Press of America. p. 366. ISBN 0-7618-1685-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Ku Kim; Jongsoo Lee (2000). The autobiography of Kim Ku, Volume 20. University Press of America. p. 366. ISBN 0-7618-1685-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- 1 2 Howard L. Boorman; Richard C. Howard; Joseph K. H. Cheng (1979). Biographical dictionary of Republican China, Volume 3. New York City: Columbia University Press. p. 56. ISBN 0-231-08957-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Korea (South). 國防部. 軍事編纂硏究所 (1999). Mi Kungmubu Hanʾguk kungnae sanghwang kwallyŏn munsŏ. 國防部軍事編纂硏究所. p. 168. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ "China: Last Phase". Time. Dec 12, 1949. Archived from the original on March 10, 2007. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Moslems Urged To Resist Russia". Christian Science Monitor. 25 Sep 1951. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Chinese Asks All Moslems to Fight Reds". Chicago Daily Tribune. 24 Sep 1951. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Gen. Pai is Dead; a Chiang Aide, 73; Key Leader in Nationalist Army Since 1920s". The New York Times. 9 December 1966. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Milestones: Dec. 9, 1966". Time. Archived from the original on October 28, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ Bai's Funeral

- ↑ "Living History in the Liuzhangli Cemetery in Taipei - Hear in Taiwan". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ↑ Michael Dillon (1999). China's Muslim Hui community: migration, settlement and sects. Richmond: Curzon Press. p. 86; 208. ISBN 0-7007-1026-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ "Religion: Chungking Meeting". Time. June 14, 1943. Archived from the original on December 14, 2008. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ Peony Dreams Retrieved 12-6-2008.

- ↑ Diana Lary (1974). Region and nation: the Kwangsi clique in Chinese politics, 1925-1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 98. ISBN 0-521-20204-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Don Alvin Pittman (2001). Toward a modern Chinese Buddhism: Taixu's reforms. University of Hawaii Press. p. 146. ISBN 0-8248-2231-5. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Diana Lary (1974). Region and nation: the Kwangsi clique in Chinese politics, 1925-1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 99. ISBN 0-521-20204-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Diana Lary (1974). Region and nation: the Kwangsi clique in Chinese politics, 1925-1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 99. ISBN 0-521-20204-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Diana Lary (1974). Region and nation: the Kwangsi clique in Chinese politics, 1925-1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 100. ISBN 0-521-20204-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Eugene William Levich (1993). The Kwangsi way in Kuomintang China, 1931-1939. M.E. Sharpe. p. 14. ISBN 1-56324-200-1. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Jonathan Fenby (2005). Chiang Kai Shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost. Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 117. ISBN 0-7867-1484-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- 1 2 Diana Lary (1974). Region and nation: the Kwangsi clique in Chinese politics, 1925-1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 124. ISBN 0-521-20204-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Hsiao-ting Lin (2010). Modern China's Ethnic Frontiers: A Journey to the West. Taylor & Francis. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-415-58264-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Barbara Tuchman's book Stilwell and American Experience in China

- ↑ "Picture of Bai and his Wife with their Children". Archived from the original on 2012-04-01. Retrieved 2010-09-25.

- ↑ "Taiwan Today - Pai Chung-hsi's tomb to center Taipei cultural park". Archived from the original on 2014-05-12. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ Allen-Ebrahimian, Bethany (2023-01-24). "One man's struggle to keep Islam alive in Taiwan". Axios. Retrieved 2023-01-27.