| 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Homodimer of 4-Hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase. Red ribbon represents iron-containing catalytic domain (with Fe 2+ represented as red-orange spheres); blue represents the oligomeric domain. Image generated from published structural data [1] | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 1.13.11.27 | ||||||||

| CAS no. | 9029-72-5 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / QuickGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | HPPD | ||||||

| Alt. symbols | HPD; PPD | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 3242 | ||||||

| HGNC | 5147 | ||||||

| OMIM | 609695 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_002150 | ||||||

| UniProt | P32754 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| EC number | 1.13.11.27 | ||||||

| Locus | Chr. 12 q24-qter | ||||||

| |||||||

4-Hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (HPPD), also known as α-ketoisocaproate dioxygenase (KIC dioxygenase), is an Fe(II)-containing non-heme oxygenase that catalyzes the second reaction in the catabolism of tyrosine - the conversion of 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate into homogentisate. HPPD also catalyzes the conversion of phenylpyruvate to 2-hydroxyphenylacetate and the conversion of α-ketoisocaproate to β-hydroxy β-methylbutyrate.[2][3] HPPD is an enzyme that is found in nearly all aerobic forms of life.[4]

Enzyme mechanism

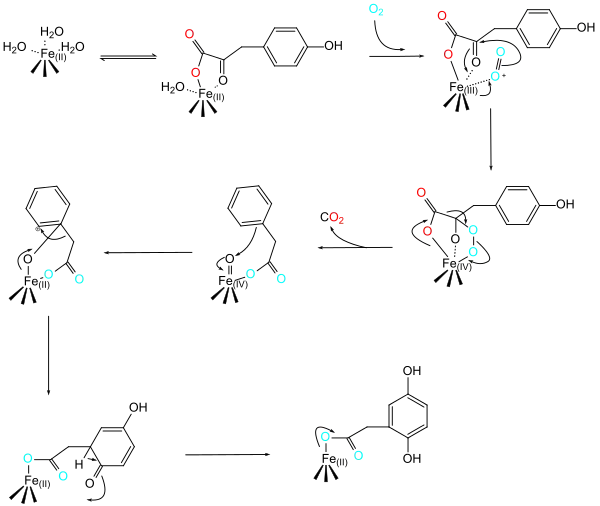

HPPD is categorized within a class of oxygenase enzymes that usually utilize α-ketoglutarate and diatomic oxygen to oxygenate or oxidize a target molecule.[5] However, HPPD differs from most molecules in this class due to the fact that it does not use α-ketoglutarate, and it only utilizes two substrates while adding both atoms of diatomic oxygen into the product, homogentisate.[6] The HPPD reaction occurs through a NIH shift and involves the oxidative decarboxylation of an α-oxo acid as well as aromatic ring hydroxylation. The NIH-shift, which has been demonstrated through isotope-labeling studies, involves migration of an alkyl group to form a more stable carbocation. The shift, accounts for the observation that C3 is bonded to C4 in 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate but to C5 in homogentisate. The predicted mechanism of HPPD can be seen in the following figure:

Structure

HPPD is an enzyme that usually bonds to form tetramers in bacteria and dimers in eukaryotes and has a subunit mass of 40-50 kDa.[7][8][9] Dividing the enzyme into the N-terminus and C-terminus one will notice that the N-terminus varies in composition while the C-terminus remains relatively constant[10] (the C-terminus in plants does differ slightly from the C-terminus in other beings). In 1999 the first X-ray crystallography structure of HPPD was created[11] and since then it has been discovered that the active site of HPPD is composed entirely of residues near the C-terminus of the enzyme. The active site of HPPD has not been completely mapped, but it is known that the site consists of an iron ion surrounded by amino acids extending inward from beta sheets (with the exception of the C-terminal helix). While even less is known about the function of the N-terminus of the enzyme, scientists have discovered that a single amino acid change in the N-terminal region can cause the disease known as hawkinsinuria.[12]

Function

In nearly all aerobic beings, 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase is responsible for converting 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate into homogentisate.[13] This conversion is one of many steps in breaking L-tyrosine into acetoacetate and fumarate.[14] While the overall products of this cycle are used to create energy, plants and higher order eukaryotes utilize HPPD for a much more important reason. In eukaryotes, HPPD is used to regulate blood tyrosine levels, and plants utilize this enzyme to help produce the cofactors plastoquinone and tocopherol which are essential for the plant to survive.[15]

Disease relevance

HPPD can be linked to one of the oldest known inherited metabolic disorders known as alkaptonuria, which is caused by high levels of homogentisate in the blood stream.[16] HPPD is also directly linked to Type III tyrosinemia[17] When the active HPPD enzyme concentration is low in the human body, it results in high levels of tyrosine concentration in the blood, which can cause mild mental retardation at birth, and degradation in vision as a patient grows older.[18]

In Type I tyrosinemia, a different enzyme, fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase is mutated and doesn't work, leading to very harmful products building up in the body.[19] Fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase acts on tyrosine after HPPD does, so scientists working on making herbicides in the class of HPPD inhibitors hypothesized that inhibiting HPPD and controlling tyrosine in the diet could treat this disease. A series of small clinical trials were attempted with one of their compounds, nitisinone were conducted and were successful, leading to nitisinone being brought to market as an orphan drug.[20][21]

Industrial relevance

Due to HPPD’s role in producing necessary cofactors in plants, there are several marketed HPPD inhibitor herbicides that block activity of this enzyme, and research underway to find new ones.[22]

References

- ↑ Fritze IM, Linden L, Freigang J, Auerbach G, Huber R, Steinbacher S (Apr 2004). "The crystal structures of Zea mays and Arabidopsis 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase". Plant Physiology. 134 (4): 1388–400. doi:10.1104/pp.103.034082. PMC 419816. PMID 15084729.; rendered with UCSF Chimera

- ↑ "Homo sapiens: 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase reaction". MetaCyc. SRI International. 20 August 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ↑ Kohlmeier M (2015). "Leucine". Nutrient Metabolism: Structures, Functions, and Genes (2nd ed.). Academic Press. pp. 385–388. ISBN 9780123877840. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ↑ Gunsior M, Ravel J, Challis GL, Townsend CA (Jan 2004). "Engineering p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase to a p-hydroxymandelate synthase and evidence for the proposed benzene oxide intermediate in homogentisate formation". Biochemistry. 43 (3): 663–74. doi:10.1021/bi035762w. PMID 14730970.

- ↑ Hausinger RP (2004). "FeII/alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent hydroxylases and related enzymes". Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 39 (1): 21–68. doi:10.1080/10409230490440541. PMID 15121720. S2CID 85784668.

- ↑ Moran GR (Jan 2005). "4-Hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 433 (1): 117–28. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.015. PMID 15581571.

- ↑ Wada GH, Fellman JH, Fujita TS, Roth ES (Sep 1975). "Purification and properties of avian liver p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate hydroxylase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 250 (17): 6720–6. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)40992-7. PMID 1158879.

- ↑ Lindblad B, Lindstedt G, Lindstedt S, Rundgren M (Jul 1977). "Purification and some properties of human 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (I)". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 252 (14): 5073–84. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)40160-8. PMID 873932.

- ↑ Buckthal DJ, Roche PA, Moorehead TJ, Forbes BJ, Hamilton GA (1987). "4-Hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase from pig liver". Metabolism of Aromatic Amino Acids and Amines. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 142. pp. 132–8. doi:10.1016/s0076-6879(87)42020-x. ISBN 9780121820428. PMID 3298972.

- ↑ Yang C, Pflugrath JW, Camper DL, Foster ML, Pernich DJ, Walsh TA (Aug 2004). "Structural basis for herbicidal inhibitor selectivity revealed by comparison of crystal structures of plant and mammalian 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenases". Biochemistry. 43 (32): 10414–23. doi:10.1021/bi049323o. PMID 15301540.

- ↑ Serre L, Sailland A, Sy D, Boudec P, Rolland A, Pebay-Peyroula E, Cohen-Addad C (Aug 1999). "Crystal structure of Pseudomonas fluorescens 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase: an enzyme involved in the tyrosine degradation pathway". Structure. 7 (8): 977–88. doi:10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80124-5. PMID 10467142.

- ↑ Tomoeda K, Awata H, Matsuura T, Matsuda I, Ploechl E, Milovac T, Boneh A, Scott CR, Danks DM, Endo F (Nov 2000). "Mutations in the 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid dioxygenase gene are responsible for tyrosinemia type III and hawkinsinuria". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 71 (3): 506–10. doi:10.1006/mgme.2000.3085. PMID 11073718.

- ↑ Zea-Rey AV, Cruz-Camino H, Vazquez-Cantu DL, Gutiérrez-García VM, Santos-Guzmán J, Cantú-Reyna C (27 November 2017). "The Incidence of Transient Neonatal Tyrosinemia Within a Mexican Population" (PDF). Journal of Inborn Errors of Metabolism and Screening. 5: 232640981774423. doi:10.1177/2326409817744230.

- ↑ Knox WE, LeMay-Knox M (October 1951). "The oxidation in liver of l-tyrosine to acetoacetate through p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate and homogentisic acid". The Biochemical Journal. 49 (5): 686–93. doi:10.1042/bj0490686. PMC 1197578. PMID 14886367.

- ↑ Mercer E, Goodwin T (1988). Introduction to Plant Biochemistry (2nd ed.). Oxford: Pergamon Press. ISBN 978-0-08-024922-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ↑ Garrod EA (1902). "The incidence of alkaptonuria: a study in chemical individuality". Lancet. 160 (4134): 1616–1620. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(01)41972-6. PMC 2230159. PMID 8784780.

- ↑ Tomoeda K, Awata H, Matsuura T, Matsuda I, Ploechl E, Milovac T, Boneh A, Scott CR, Danks DM, Endo F (Nov 2000). "Mutations in the 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid dioxygenase gene are responsible for tyrosinemia type III and hawkinsinuria". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 71 (3): 506–10. doi:10.1006/mgme.2000.3085. PMID 11073718.

- ↑ Hühn R, Stoermer H, Klingele B, Bausch E, Fois A, Farnetani M, Di Rocco M, Boué J, Kirk JM, Coleman R, Scherer G (Mar 1998). "Novel and recurrent tyrosine aminotransferase gene mutations in tyrosinemia type II". Human Genetics. 102 (3): 305–13. doi:10.1007/s004390050696. PMID 9544843. S2CID 19425434.

- ↑ National Organization for Rare Disorders. Physician’s Guide to Tyrosinemia Type 1 Archived 2014-02-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Lock EA, Ellis MK, Gaskin P, Robinson M, Auton TR, Provan WM, Smith LL, Prisbylla MP, Mutter LC, Lee DL (Aug 1998). "From toxicological problem to therapeutic use: the discovery of the mode of action of 2-(2-nitro-4-trifluoromethylbenzoyl)-1,3-cyclohexanedione (NTBC), its toxicology and development as a drug". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 21 (5): 498–506. doi:10.1023/A:1005458703363. PMID 9728330. S2CID 6717818.

- ↑ "Nitisinone (Oral Route) Description and Brand Names -". Mayo Clinic.

- ↑ van Almsick A (2009). "New HPPD-Inhibitors - A Proven Mode of Action as a New Hope to Solve Current Weed Problems". Outlooks on Pest Management. 20 (1): 27–30. doi:10.1564/20feb09.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link)

Further reading

- Saito I, Chujo Y, Shimazu H, Yamane M, Matsuura T (Sep 1975). "Nonenzymic oxidation of p-hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid with singlet oxygen to homogentisic acid. A model for the action of p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate hydroxylase". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 97 (18): 5272–7. doi:10.1021/ja00851a042. PMID 1165361.

- Wada GH, Fellman JH, Fujita TS, Roth ES (Sep 1975). "Purification and properties of avian liver p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate hydroxylase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 250 (17): 6720–6. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)40992-7. PMID 1158879.

- Johnson-Winters K, Purpero VM, Kavana M, Nelson T, Moran GR (Feb 2003). "(4-Hydroxyphenyl)pyruvate dioxygenase from Streptomyces avermitilis: the basis for ordered substrate addition". Biochemistry. 42 (7): 2072–80. doi:10.1021/bi026499m. PMID 12590595.