| Basilica Shrine of Our Lady of Knock, Queen of Ireland | |

|---|---|

Cnoc Mhuire | |

Sanctuary of Our Lady of Knock | |

Basilica Shrine of Our Lady of Knock, Queen of Ireland | |

| 53°47′32″N 8°55′04″W / 53.792099°N 8.917659°W | |

| Location | Knock, County Mayo |

| Country | Ireland |

| Language(s) | English, Irish |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Tradition | Roman Rite |

| Website | knockshrine |

| History | |

| Dedication | Our Lady of Knock |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural type | Modern |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 10,000 |

| Administration | |

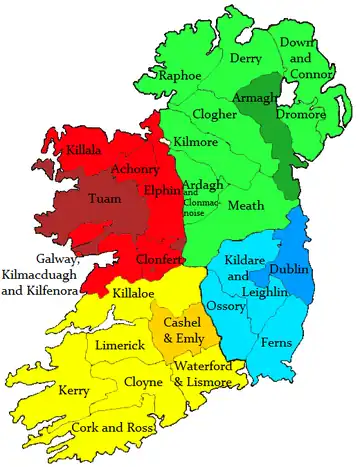

| Archdiocese | Tuam |

| Deanery | Claremorris |

| Clergy | |

| Rector | Father Richard Gibbons (Knock Parish) |

The Sanctuary of Our Lady of Knock, commonly referred to as Knock Shrine, is a Roman Catholic pilgrimage site and national shrine in the village of Knock, County Mayo, Ireland, where locals claimed to have seen an apparition in 1879 of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Saint Joseph, Saint John the Evangelist, angels, and Jesus Christ (the Lamb of God).

Apparition

The evening of Thursday, 21 August 1879, was a very wet night. At about 8 o'clock it was raining as Mary Byrne, who was from the village, was going home with the priest's housekeeper, Mary McLoughlin. Byrne stopped suddenly when she saw the gable of the church. She claimed she saw three life-size figures. She ran home to tell her parents and soon others from the village gathered. The witnesses said they saw an apparition of Our Lady, Saint Joseph and Saint John the Evangelist at the south gable end of the Church of Saint John the Baptist. Behind them and a little to the left of Saint John was a plain altar. On the altar was a cross and a lamb, with angels.[1] A farmer, about half a mile away from the scene, later described what he saw as a large globe of golden light above and around the gable, circular in appearance.[2] For nearly two hours a group that fluctuated between two and perhaps as many as twenty-five stood or kneeled, gazing at the figures. It was raining.[3] Those identified as witnesses (and relatives) were Mary Byrne/Margaret Beirne, aged 29, and her mother Margaret Beirne, aged 68, her younger adult sister Margaret Beirne, her younger adult brother Dominick Beirne, her eight-year-old niece Catherine Murray, and Dominick Beirne, who was an elder cousin, Dominick's five-year-old nephew John Curry, and Patrick Beirne, who was possibly also a relative. It was 11-year-old Patrick Hill who is thought to have given the most detailed description of the vision.[4]

The apparitions, for believing Catholics, held significant eschatological significance. Much work has been done to interpret the message received in the village by Catholic eschatological scholars such as Emmett O'Reagan.[5]

Description

| Our Lady of Knock | |

|---|---|

The venerated image enshrined within the Knock Shrine | |

| Location | Knock, County Mayo |

| Date | 1879 |

| Type | Marian apparition |

| Approval | 1879[6] Archbishop John MacHale Archdiocese of Tuam |

| Shrine | Sanctuary of Our Lady of Knock, Knock, County Mayo, Republic of Ireland |

The vision of Mary was described as being beautiful, standing a few feet above the ground. She was described as wearing a white cloak, hanging in full folds and fastened at the neck. She was described as "deep in prayer", with her eyes raised to heaven, her hands raised to the shoulders or a little higher, the palms inclined slightly to the shoulders.[2]

Saint Joseph was described as wearing white robes and standing at the Virgin's right hand. His head was described as bent forward from the shoulders towards the Blessed Virgin. Saint John the Evangelist stood to the left of the Blessed Virgin. He was dressed in a long robe and wore a mitre. He was partly turned away from the other figures. Some witnesses reported that Saint John appeared to be preaching and that he held open a large book in his left hand. Others did not. To the left of Saint John some said there was an altar with a lamb on it with a cross standing on the altar behind the lamb.[7]

Those who witnessed the apparition stood in the rain for up to two hours reciting the Rosary. When the apparition began there was good light, but although it then became dark, witnesses said they could still see the figures. They said the apparitions did not flicker or move in any way. The witnesses reported that the ground around the figures remained completely dry during the apparition although the wind was blowing from the south.[2]

The entire apparition wall was soon torn apart by pilgrims chipping out the cement, mortar, and stones for souvenirs and to use for cures.[8]

Church Commissions of inquiry

An ecclesiastical Commission of inquiry was established by the Archbishop of Tuam, Most Rev. Dr. John MacHale, on 8 October 1879. The Commission consisted of Irish scholar and historian, Canon Ulick Bourke, Canon James Waldron, as well as the parish priest of Ballyhaunis and Archdeacon Bartholomew Aloysius Cavanagh. Depositions of witnesses were taken in the ensuing months. The deliberations of the commission, referred only to the occurrence on 21 August 1879, which omitted "subsequent phenomena", and as a result, there exists no official record for events that occurred after that date.[9]

The evidence which was the commission's duty to record, satisfied all the members and was deemed trustworthy. Among the considerations were whether the apparition emanated from natural causes, and whether there was any positive fraud. In the first cited particular, it was reported that no solution as from natural causes could be offered; and in the second consideration, that such a suggestion had never, even remotely, been entertained.[9] The commission's final verdict was that the testimony of all the witnesses taken as a whole was trustworthy and satisfactory.

As most of the documents from the early years at Knock were assumed to have been lost, a second Commission of inquiry, in 1936, was forced to rely upon interviews with the last of the surviving witnesses (who confirmed the evidence they gave to the first Commission), their children, press reports and devotional works printed in the 1880s, which portrayed the original reports in a positive light. The surviving witnesses confirmed the evidence they gave to the first Commission.[1]

The growth of railways and the appearance of local and national newspapers fuelled interest in the small Mayo village. Reports of "strange occurrences in a small Irish village" were featured almost immediately in the international media, notably The Times (of London). Newspapers from as far away as Chicago sent reporters to cover the Knock phenomenon. Canon Ulick Bourke joined Timothy Daniel Sullivan and Margaret Anna Cusack in developing Knock as a national Marian pilgrimage site. Knock pilgrimages combined traditional Irish practices like rounds of the church and all-night vigils with devotions like the stations of the cross, benediction, processions, and the recitation of litanies. Priests associated with the Fenian movement often led pilgrimages to Knock.[3]

John White sees the silence of the apparition related to a cultural change occurring at that time. "It was necessary for Cavanagh to preach in English and Irish each Sunday as the schools saw to the replacement of Irish with English as the language of the young. This linguistic crisis may be connected with the silence of the Knock visions, as the oldest witness, Bridget Trench, had no English, while the youngest, six-year-old John Curry, was being educated with no Irish."[3]

Sceptical analysis

According to Joe Nickell, in addition to "serious discrepancies" in the witnesses' accounts, it is possible for natural phenomena to account for the apparition. With the help of an astronomer who recreated the sky of the time via computer, it was determined that the evening sun was above the horizon for the duration of the event. There was also a school near the site with a wall angled toward the south gable of the church. The suggestion is that the sun served as the light source, which reflected off the school's windows (presumed to have been there) and produced a "natural version of a magic-lantern effect". Nickell explains that "odd shapes [from diffuse reflections] could produce the requisite pareidolia ... effects in susceptible individuals, especially those who were motivated to see something "miraculous" and were familiar with similar holy pictures."[10] Investigator Melvin Harris suggested that a priest may have used a mirror to reflect a magic lantern projection onto the wall from the upper window of the chapel rather than from outside. [11]

Modern era

People who claim to have been cured at Knock still leave crutches and sticks at the spot where the apparition is believed to have occurred.[12] Each Irish diocese makes an annual pilgrimage to the Marian Shrine and the nine-day Knock novena attracts pilgrims every August.[13] The miracle is also known as Our Lady of Knock by the church.

- On All Saints' Day, 1945, Pope Pius XII blessed the banner of Knock from St Peter's Basilica in Rome and decorated it with a special medal.[8]

- On Candlemas Day in 1960, Pope John XXIII presented a special candle to Knock.[8]

- On 6 June 1974, the foundation stone for the Basilica of Our Lady, Queen of Ireland, at Knock, was blessed by Pope Paul VI.[8]

- On 30 September 1979, Pope John Paul II visited the shrine to commemorate the centenary of the apparition. During that historic visit, the Pope addressed the sick and nursing staff, celebrated Mass, established the shrine church as a basilica, presented a candle and the Golden Rose to the shrine and knelt in prayer at the apparition wall.[12]

- On 26 August 2018 Pope Francis visited the shrine at Knock as part of a visit to Ireland for the 9th World Meeting of Families

- On 14 April 2023 US President Joe Biden visited the shrine which was closed to the public during his visit

The complex incorporates five churches including the Apparition Chapel, Parish Church and Basilica, a Religious Books' Centre, Caravan and Camping Park, Knock Museum, Café le Chéile and Knock House Hotel. Services at the Shrine include organised pilgrimages, daily Masses and Confessions, Anointing of the Sick, Counselling Service, Prayer Guidance and Youth Ministry.[14] While the original church still stands, a new Apparition chapel with statues of Our Lady, St Joseph, the Lamb and St John the Evangelist, has been built next to it. Knock Basilica is a separate building showing a tapestry of the apparition.[12]

| Part of a series on the |

| Mariology of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

|

Recent history

Mother Teresa of Calcutta visited the Shrine in June 1993.[15]

Ireland's National Eucharistic Congress was held at the Marian Shrine in Knock over 25 and 26 June in 2011. An estimated 13,000 pilgrims attended.[13]

Though it remained for almost 100 years a major Irish pilgrimage site, Knock established itself as a world religious site in large measure during the last quarter of the twentieth century, largely due to the work of its longtime parish priest Monsignor James Horan. Horan presided over a major rebuilding of the site, with the provision of a new large Knock Basilica (the second in Ireland) alongside the old church. Horan secured from the Taoiseach (prime minister), Charles Haughey, millions of pounds of state aid to build an airport 19 kilometres away, near Charlestown.

On 13 May 2017, Cardinal Archbishop Timothy M. Dolan celebrated a requiem mass when John Curry, the youngest witness to the Knock apparition, was reinterred in St. Patrick's Old Cathedral cemetery in Lower Manhattan after being disinterred from an unmarked grave on Long Island.[16]

Parish priest

The parish priest at the time of the apparition was The Very Reverend Bartholomew Aloysius Cavanagh, who was also Archdeacon of the diocese.[17] He was appointed parish priest of Knock-Aghamore in 1867, and was about 58 at the time of the apparition. He died in 1897 and is buried in the Old Church.

See also

References

- 1 2 "The Story of Knock", Knock Shrine

- 1 2 3 Fr. James OFM. "The Story of Knock", Knock Shrine Annual, 1950

- 1 2 3 White, John. "The Cusack Papers; new evidence on the Knock apparition", 18th–19th Century Social Perspectives, 18th–19th – Century History, Issue 4 (Winter 1996), Vol. 4

- ↑ "Knock, visionaries of (act. 1879)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/52701. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Retrieved 25 January 2021. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ O'Reagan (17 March 2017). "Our Lady of Knock and Opening of the Sealed Book". Unveiling the Apocalypse.

- ↑ "The Story of Knock: 1879". Knock Shrine. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

On 8 October 1879, Archbishop Mac Hale of Tuam set up an ecclesiastical Commission of Enquiry to investigate the Apparition. It consisted of Canon Ulick Burke, PP Claremorris, Canon James Waldron of Ballyhaunis, Archdeacon Cavanagh, PP, Knock and 6 local curates. The testimonies of all 15 official witnesses to the Apparition were found to be trustworthy and satisfactory.

- ↑ "The Apparition at Knock", Knock Shrine Association of America

- 1 2 3 4 Haggerty, Bridget. "Our Lady of Knock Shrine – Place of Mystery and Miracles", Irish Culture and Customs

- 1 2 Carey, F. P. "Knock and its Shrine" (PDF). catholicpamphlets.net, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ↑ Nickell, Joe (2017). "Miracle Tableau: Knock, Ireland, 1879". Skeptical Inquirer. 41 (2): 26–28. Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ↑ "The 'Miracle' at Knock". www.thefreelibrary.com. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- 1 2 3 Geraghty, Joan. "Knock Shrine, the holy site", Mayo News, 18 July 2012

- 1 2 "Ireland: new Parish Priest for National Shrine at Knock", Independent Catholic News, 3 February 2012

- ↑ "'Knock Shrine', Tourism Ireland". Archived from the original on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ↑ "Knock, Ireland's National Marian Shrine", Mayo, Ireland

- ↑ Barry, Dan (12 May 2017). "A Worldly Accomplishment Is Rewarded With a Heavenly One". The New York Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on 12 May 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ↑ Archdeacon Cavanagh

Further reading

- John MacPhilpin. The Apparitions and Miracles at Knock. PJ Kennedy. 1904. Also here

- Sister Mary Francis Clare. Three Visits to Knock. PJ Kennedy. 1904

- Neary, Tom. I Saw Our Lady