Orpheum Theatre Group | |

| |

| Address | 203 South Main Street Memphis, Tennessee United States |

|---|---|

| Public transit | |

| Operator | Orpheum Theatre Group |

| Type | Performing arts center |

| Capacity | 2,308 |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 1928 |

| Reopened | 1984 |

| Website | |

| www | |

Orpheum Theatre | |

| Location | 203 South Main Street |

| Coordinates | 35°8′24″N 90°3′19″W / 35.14000°N 90.05528°W |

| Architect | C.W. Rapp and George L. Rapp |

| Architectural style | Renaissance |

| NRHP reference No. | 77001289 |

| Added to NRHP | August 15, 1977 |

The Orpheum Theatre, a 2,308-seat venue listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is located in downtown Memphis, Tennessee, on the southwest corner of the intersection of South Main and Beale streets. The Orpheum, along with the Halloran Centre for Performing Arts & Education, compose the Orpheum Theatre Group, a community-supported nonprofit corporation that operates and maintains the venues and presents education programs.[1]

Entertainment and Community Programming

Since 1977, the Orpheum has been the Mid-South home of touring Broadway productions. The Orpheum's two venues also host performances by Ballet Memphis, various concerts, comedians, a summer movie series, a family series of educational programs, and local cultural and community events such as Memphis in May, International Blues Challenge, and special Elvis Week events. These performances, along with the theater's numerous educational offerings, are an integral component of the continued revitalization of downtown Memphis.

Preservation

Since it first opened in 1928, the Orpheum has dazzled patrons with its artisan millwork, gilding, original fixtures, a Mighty Wurlitzer organ, and architectural beauty. Saved by the Memphis Development Foundation (MDF) in 1977,[2] the Orpheum was one of the first buildings in Memphis placed on the National Register of Historic Places.[3] Under the leadership of the MDF, in the last 35 years the Orpheum has undergone more than $15 million in renovation and improvements that have made it a world-class performing arts facility while preserving the historical and architectural integrity of the vaudeville palace.

Early history

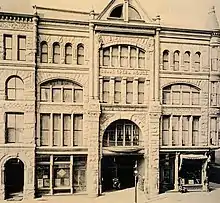

The Grand Opera House

In 1890, the Grand Opera House opened on the corner of Main and Beale streets, and was billed as the most classy theater outside New York City. Vaudeville was the main source of entertainment at the time, featuring singers, musicians, and magicians. The Grand became part of the Orpheum Circuit in 1907, and the theater became known as the Orpheum.

Vaudeville at the Orpheum was successful for almost two decades. Then in 1923, after a show that featured singer Blossom Seeley, a fire started and the theater burned to the ground.[4]

The New Orpheum

On November 19, 1928, the new Orpheum theatre opened on the original site of the Grand Opera House. Designed by architects Rapp and Rapp of Chicago, the Orpheum seats just over 2,300 people at a cost of $1.6 million. The new Orpheum was twice as large as her predecessor and featured glittering gold and silver leaf, marble, lush carpets, and antique crystal chandeliers and a Wurlitzer organ.[2][5]

As vaudeville's popularity waned, Michael A. Lightman's movie theater chain purchased the Orpheum in 1940 and changed its name to the Malco, presenting first-run movies.[6] In 1976, Lightman decided to sell the building, as intimate multiplex theaters were proving more lucrative than large single-screen venues.[2] There was talk of demolishing the old theater. However, in 1977 the Memphis Development Foundation bought the theater, restored its former name of Orpheum, and began bringing Broadway productions and concerts back to the theater.[2][7] In 1980, MDF hired Pat Halloran as its president and CEO, a position he held for the next 35 years.[8]

The Wurlitzer Organ

Though talking pictures had been successfully introduced in 1927 and the new Orpheum Theatre was equipped with talking picture equipment on its opening in October 1928, it was still common for vaudeville and movie theatres to be equipped with a theatre pipe organ for use either alone or in combination with other instruments. The theatre owners contracted with the Wurlitzer Company for a three manual, 13 rank pipe organ, style 240. The instrument was shipped from the factory on September 25, 1928, and given opus number (serial number) 1956.[9] The pipes are located in two purpose-built, hidden chambers behind the large curtained arches flanking the proscenium, at approximately the height of the forward-most chandeliers. The "Main Chamber" is on house right with eight ranks (sets) of pipes, and the "Solo Chamber" has five ranks of pipes on the house left side. In total there are just over 1,100 pipes, ranging from approximately 16 feet (4.9 m) to the size of a pencil. Additionally, most of the organ's percussion instruments, marimba, xylophone, drums and so forth, are placed in the Solo Chamber. The organ is also equipped with a number of sound effects to accompany silent movies: bird whistles, fire alarms, horse hoofs, etc. The organ console was placed on a screw-drive lift at the left side of the orchestra pit allowing the organist to raise the console into the audience's view while playing or lower it out-of-sight when not in use. Additionally, a large electric blower to provide the organ's compressed air, is placed in a sound-proof room below the stage.

A minor stage fire in the 1950s caused the original stage curtains to burn and fall onto the organ console, badly scorching its original mahogany finish. For un-recorded reasons it was decided to paint the console white rather than refinish the scorched wood. In subsequent years, additional gold colored trim has been added to the console.

In the 1980s, an additional rank of pipes was donated to the theatre to provide the organ with a stronger bass. This set of 44 large wooden pipes was built in the 1910s by the Felgemaker Organ Company and installed by then organist John Hiltonsmith (1960-2014).[10]

In June 2017, Orpheum launched a campaign to rebuild the organ for its upcoming 90th anniversary. The goal is to raise $500,000 to restore portions of the instrument that no longer work.[11]

Reopening

1982 building restoration

Fifty-four years had taken a toll on the "South's Finest Theatre". The Orpheum closed on Christmas Day 1982 to begin a $5 million renovation to restore its 1928 opulence. Beyond the cleaning, decorative, and lighting changes of this once-beautiful building, significant improvements included heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning system renovations; restroom enhancements; and dressing room reconfigurations and redecorations. Other changes involved the construction of two functional loading docks, an expanded orchestra pit, and a hydraulic pit lift that added extra space to the front stage area when an orchestra wasn't required.[12]

Restoration crews also cleaned the exterior of the building, repairing and repainting the vertical Orpheum sign and the famous theater marquee. To meet audiences' growing needs, the theatre constructed a parlor with restrooms, a large concessions area, and a box office on the south side of the grand lobby. Later, it created a "green room" — now the Broadway Club — at the northeast corner of the lobby, in space previously occupied by a men's clothing store called Bert's. When work completed, the Orpheum had a seating capacity of 2,491, including 28 new private suites.

Subsequent renovations

In 1996, the Orpheum Theatre tackled its biggest renovation ever, an $8-million project to expand the stage and backstage areas as new touring productions needed more space than the facility offered. Improvements to accommodate growing productions began in spring 1996 and continued through fall 1997.

When the curtain opened on the 1997-98 Orpheum Broadway Season, the extended stage was 50 feet (15 m) deep with a larger orchestra pit. The renovation also created 13 new dressing rooms, a special warm-up area for the ballet company and added two additional loading bays, doubling the previous capacity. It also added needed space for storage and offices. The walls throughout the theater were repainted and gold-leafed, and new technical equipment was installed. The theater had gotten a complete face-lift.[6][15]

Thanks to these improvements, the Orpheum has been able to host presented numerous large-scale Broadway productions, including Disney's Lion King, Wicked, CATS, and Les Miserables, while continuing to offer performances from great entertainers like Bob Dylan, Jerry Seinfeld, Mary J. Blige, Sarah McLachlan, John Mellencamp, Harry Connick Jr., Tyler Perry, Tony Bennett, and others.[1]

The third renovation occurred simultaneously with construction of the Halloran Centre. Work began in 2014 and including an upgraded sound system, renovated seats, expanded restroom facilities, decorative repainting, expanding legroom and realigning seats for patron comfort. To achieve this, the theatre eliminated two rows of seats in the center orchestra section reducing the seating capacity to the current 2,308.[16] Work also upgraded emergency systems and staff office space.[17]

Halloran Centre for Performing Arts & Education

In 2013, Orpheum launched a capital campaign with a goal of $15 million and hired The Crump Firm to design a new facility adjacent to the Orpheum to house its growing educational programs. In March 2014, Orpheum broke ground after raising almost $10 million. After long-time president Pat Halloran announced his retirement in 2014, the Memphis Development Foundation's board of directors voted to name it in his honor.[18]

The Halloran Centre for Performing Arts & Education, adjacent to the Orpheum Theatre at 225 South Main Street, opened September 23, 2015, as the new home for the Orpheum's community and education programs. Members of the community were invited to explore the new facility which houses 39,000 square feet containing a 361-seat theater, meeting rooms and rehearsal space to accommodate concerts, dance, and other community events, including Indie Memphis Film Festival and Collage dance Collective.[19] The Halloran Centre is also available for private gatherings and business meetings.[1]

While, construction was ongoing at Halloran Centre, the Orpheum also underwent another round of improvements.

Orpheum Theatre Group

Upon Halloran's retirement at the end of 2015, the Memphis Development Foundation hired Brett Batterson as the new president and CEO.[20] With this transition in leadership, the Memphis Development Foundation undertook a self-evaluation process, reimagining its vision, mission statement, and name. In May 2016, the organization adopted its new identity and an updated logo and brand design to become the Orpheum Theatre Group, a nonprofit corporation.[1]

Continued growth

As the Orpheum improved its on-stage offerings, efforts to advance arts education in the Mid-South were becoming just as successful. By 2012, almost 50,000 students, teachers, and families were participating in education and community outreach programs.[1]

In March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, The Orpheum canceled shows during March and April, including A Bronx Tale, prioritizing general public health and the safety of traveling performers.[21]

Paranormal occurrences

One of the Orpheum's most famous patrons is Mary, the ghost of a 12-year-old girl.[22] Stories vary about how Mary's spirit came to stay at the Orpheum, but most suggest she was injured in an accident. Some scenarios include a 1921 car accident, while others say she was injured by a trolley in 1928 and carried inside, where she died.[23]

For more than 50 years, a variety of strange and unexplained incidents at the Orpheum have convinced many of the people who have been associated with the theater that the place is haunted. Mary has consistently been described by witnesses to have braided brown hair and a white dress and is a little shy.[24]

Performers have offered the most frequent descriptions of the ghost. Stories abound about flickering lights, tools emptied into commodes, doors swinging open and shutting loudly – events that even spooked Yul Brynner while rehearsing for The King & I in 1982.[23] Countless times over the past 50 years, performers have noticed a little girl in what looks like a school uniform sitting in a side box on the mezzanine. Her blank stare and ethereal appearance have upset some of those who have seen her. Yet, Mary is never known to have disrupted a performance.[23][25]

A group of paranormal researchers from the University of Memphis, then known as Memphis State University, found that a ghost does, as legend suggested, live in the Orpheum and call herself Mary. Using séances and a Ouija board, the researchers found a contrasting story to the more common legend of the streetcar incident. They believe the little girl died in 1921 in some sort of falling accident in the downtown area, which had nothing to do with the theater.[23][24] According to the University of Memphis group, Mary "wandered into the Orpheum after her death, and she liked it. So she stayed."[25]

Memphis historian Vincent Astor, along with other researchers and patrons, have claimed to be aware of as many as six other spirits inhabiting the Orpheum, including a male, known to some as David, who is waiting to escort Mary to the other side. Since she refuses to leave the beautiful old theater, however, he cannot leave either and is therefore spending eternity in the theater with her.[26]

Others include an "unhappy" spirit, referred to as Eleanor, in the foyer of the balcony. Astor described a cold feeling in the balcony – like putting "your hand in a tub full of raw liver" – but does not believe that Eleanor is a malevolent spirit.[26]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "History of The Orpheum Theatre Group". Orpheum Theatre. Retrieved 2017-07-28.

- 1 2 3 4 Williams, Noni (June 23, 1977). "New Memphis Landmark: The 50-Year-Old Orpheum". Memphis Daily News.

- ↑ Williamson, Floyd (August 15, 1977). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ↑ "'Music Hall of the South' was never just a theatre". The Commercial Appeal. January 16, 1965.

- ↑ Halloran, Pat (2015). Phases and Stages of a Grand Dame: The Story of the Orpheum. Image Publishing.

- 1 2 "Orpheum Theatre". Cinema Treasures. Retrieved 2017-07-28.

- ↑ "Hopkins Grand Opera, Orpheum Theatre, Malco Theatre, Memphis". www.historic-memphis.com. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- ↑ Beifuss, John (December 5, 2014). "Exiting the Stage: Pat Halloran embarks on his final year at the Orpheum helm". The Commercial Appeal. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

- ↑ Junchen, David (2005). The Wurlitzer Pipe Organ, an Illustrated History. American Theatre Organ Society. p. 687. ISBN 978-0976333807.

- ↑ "John Hiltonsmith". ObitTree. 4 September 2023.

- ↑ Boswell, Makayla (June 8, 2017). "Orpheum launches campaign to restore Mighty Wurlitzer organ". The Commercial Appeal. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ↑ Branston, John (March 18, 1983). "Restoration keeps pace at Orpheum". The Commercial Appeal.

- ↑ Fulbright, Alice (January 7, 1984). "Dance will follow on heels of Champagne & Gershwin". The Commercial Appeal.

- ↑ "Resurgence in downtown; Curtain going up Saturday at new Orpheum". Mid-South Business Journal. January 2–6, 1984.

- ↑ Smith, Whitney (November 7, 1997). "Phantom to rise on stage as dust settles". The Commercial Appeal.

- ↑ Bailey Jr., Thomas (October 31, 2014). "Orpheum improves sound, phasing upgrades to seats, restrooms". The Commercial Appeal. Retrieved 2017-07-28.

- ↑ McCoy, Chris (August 23, 2016). "Orpheum Gets a Makeover". Memphis Flyer. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ↑ Richens, Mark (May 26, 2015). "New Orpheum center to be named after longtime president Pat Halloran". The Commercial Appeal. Retrieved 2017-07-28.

- ↑ Sheffield, Michael (September 22, 2015). "Halloran Centre grand opening scheduled for September 23". Memphis Business Journal. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- ↑ Bailey Jr., Thomas (September 27, 2015). "Chicago's Batterson selected to take reins of Orpheum". The Commercial Appeal. Retrieved 2017-07-28.

- ↑ Orpheum Theatre cancels "A Bronx Tale" due to coronavirus concerns, WMC Action News 5, 23 March 2020, retrieved 1 April 2020

- ↑ Stout, Cathryn (October 31, 2008). "Four Halloween ghost stories to get you into the spirit". The Commercial Appeal. Retrieved 2017-07-28.

- 1 2 3 4 Brown, Alan (October 14, 2002). Haunted Places in the American South. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 208–209. ISBN 978-1578064779.

- 1 2 Ewing, James (October 1, 1986). It Happened in Tennessee. Rutledge Hill Press. pp. 74–76. ISBN 978-0934395311.

- 1 2 "Memphis Hauntings, Orpheum Theatre". www.hauntedhouses.com. Archived from the original on 2016-09-15. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- 1 2 Orpheum Memphis (2012-10-29), Orpheum Ghost Stories with Vincent Astor, archived from the original on 2021-12-19, retrieved 2016-07-12

External links

- Dark Destinations - Orpheum Theatre Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine - info on haunted locations