| Oriental bittersweet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Celastrales |

| Family: | Celastraceae |

| Genus: | Celastrus |

| Species: | C. orbiculatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Celastrus orbiculatus | |

Celastrus orbiculatus is a woody vine of the family Celastraceae.[1] It is commonly called Oriental bittersweet,[2][3][4] as well as Chinese bittersweet,[3] Asian bittersweet,[4] round-leaved bittersweet,[4] and Asiatic bittersweet. It is native to China, where it is the most widely distributed Celastrus species, and to Japan and Korea.[5] It was introduced into North America in 1879,[6] and is considered to be an invasive species in eastern North America.[7] It closely resembles the native North American species, Celastrus scandens, with which it will readily hybridize.[8]

Description

The defining characteristic of the plant is its vines: they are thin, spindly, and have silver to reddish brown bark. They are generally between 1 and 4 cm (0.4 and 1.6 in) in diameter. However, if growth is not disturbed, vines can exceed 10 cm (3.9 in) and when cut, will show age rings that can exceed 20 years. When Celastrus orbiculatus grows by itself, it forms thickets; when it is near a tree the vines twist themselves around the trunk as high as 40 feet. The encircling vines have been known to strangle the host tree to death or break branches from the excess weight, which is also true of the slower-growing American species, C. scandens. The leaves are round and glossy, 2–12 cm (0.8–4.7 in) long, have toothed margins and grow in alternate patterns along the vines. Small green flowers are borne on axillary cymes. The fruit is a 3-valved capsule, which dehisces to reveal bright red arils that cover the seeds. All parts of the plant are poisonous.[9]

Range and habitat

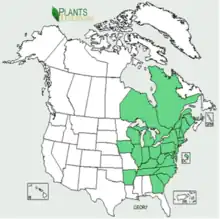

Due to systematic disturbances to eastern forests for wood production and recreation, Oriental bittersweet has naturalized to landscapes, roadsides, and woodlands of eastern North America. In the United States, it can be found as far south as Louisiana, as far north as Maine, and as far west as the Rocky Mountains.[10][11] It prefers mesic woods, where it has been known to eclipse native plants.[12]

Cultivation

Celastrus orbiculatus is cultivated as an ornamental plant. In the UK, it has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[13]

As an invasive species

Oriental bittersweet is a strong competitor in its environment, and its dispersal has endangered the survival of several other species. One attribute that contributes to the success of this species is having attractively colored fruit. As a result, it is eaten by mammals and birds, which excrete the seeds to different locations.

The introduction of Oriental bittersweet into new areas threatens the local flora because the native plants then have a strong competitor in the vicinity. The species is native to Eastern Asia, but was introduced to the US for aesthetic purposes.[14] It has been used in floral arrangements, and because of improper disposal the plant has been recklessly introduced into areas, affecting the ecology of over 33 states from Georgia to Wisconsin, and parts of the Appalachians.[14] The organism grows primarily in the perimeter of highly vegetative areas, allowing it to readily access the frontier of resources. Oriental bittersweet's ability to grow in a variety of environments has proven to be detrimental to many plant species along the Appalachian mountains and is moving more towards the West as time progresses.[15][16][17]

Oriental bittersweet employs multiple invasive and dispersal strategies allowing it to outcompete the surrounding plant species in non-native regions. This is a strong reason why the control of the species presents difficulties to manage.[18] The plant's invasion has created diverse ecological, managerial, and agricultural complications making it a focus of environmental conservation efforts.

Response to abiotic factors

Oriental bittersweet can be found growing in areas that are high and steep. When placed in 10 different sites with varying light intensity and nitrogen concentration, Oriental bittersweet was found to have higher aboveground biomass as well as a lower mortality rate in comparison to its congener species, Celastrus scandens (American bittersweet). This species is able to outcompete other species by more effectively responding to abiotic conditions such as sunlight. In diverse abiotic conditions (such as varying sunlight intensity and nitrogen concentrations), Oriental bittersweet has a mortality rate of 14% in comparison to the American bittersweet, which has a mortality rate of 33%.[19] Oriental bittersweet cannot thrive as efficiently when placed in extremely wet and dry environments; however, it flourishes in moderate rainfall environments which leads to an increased growth rate.

Sunlight is one of the most vital resources for Oriental bittersweet. As demonstrated by controlled experiments, Oriental bittersweet grows more rapidly in environments that fare a higher amount of sunlight. In a study where populations received above 28% sunlight, it exhibited a higher amount of growth and biomass.[19] This study used layers of woven cloth to control the percentage of available sunlight. In this experiment, the TLL ratio (the living length of stems on each plant) increased when Oriental bittersweet was exposed to higher amounts of sunlight.[19] If Oriental bittersweet was exposed to 2% sunlight, then the TLL ratio decreased.[19] Oriental bittersweet can increase in biomass by 20% when exposed to 28% sunlight rather than 2%. The plant's strong response to sunlight parallels its role as an invasive species, as it can outcompete other species by fighting for and receiving more sunlight. Although growth ratios decrease when Oriental bittersweet is exposed to 2% sunlight (due to a decrease in photosynthetic ability), it still exhibited a 90% survival rate.[20] Experimental data has indicated that Oriental bittersweet has a strong ability to tolerate low light conditions "ranging on average from 0.8 to 6.4% transmittance".[21] In comparison to its congener American bittersweet, when placed in habitats with little light, Oriental bittersweet was found to have increased height, increased aboveground biomass, and increased total leaf mass.[20][21] Oriental bittersweet, in comparison to many other competing species, is the better competitor in attaining sunlight.

Temperature is another variable that plays a role in Oriental bittersweet's growth and development as an invasive species. Unlike other invasive species, high summer temperatures have been shown to inhibit plant growth. Oriental bittersweet has also been shown to be positively favored in habitats experiencing high annual precipitation. This is noteworthy as it contrasts sharply with other common invasive species such as Berberis thunbergii and Euonymus alatus which have been shown to have a decreased probability of establishment when placed in environments experiencing high annual precipitation.[22]

Compared to other invasive species analyzed in a recent study, Oriental bittersweet was more prevalent in landscapes dominated by developed areas.[22] Open and abandoned habitats were also found to positively influence the spread of the plant compared to other invasive species.[22] Additionally the species is heavily favored in edge habitats. This ability to live in various environmental conditions raises the concern of the plant's dispersal.

Biotic interactions

Mutualistic interactions

A determining factor regarding Oriental bittersweet's ability to outcompete native plant species is its ability to form mutualistic associations with mycorrhizal fungi, specifically arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi.[23] Oriental bittersweet growth is highly dependent on the absorption of phosphorus. In a recent study, growth was found to be greater when arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi were present in soil with low phosphorus concentrations, compared to when the plant was placed in an environment with high soil phosphorus concentrations with no arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi were present.[23] The results from this study show the importance of symbiotic relationships in allowing Oriental bittersweet to effectively uptake nutrients from its surroundings. Additionally, the symbiotic relationship with mycorrhizae allows this invasive species to utilize less of its energy in root biomass to absorb necessary nutrients. This may be crucial in allowing Oriental bittersweet to act as an effective invasive species as it is able to allocate more energy to its aboveground biomass instead of its belowground biomass; a significant point regarding this plant's invasiveness relies on photosynthetic ability and reproductive capacity.[23] The symbiotic relationship established with fungi only occurs with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, while no such relationship has been observed with ectomycorrhizal fungi. These studies have shown that suitable mycorrhizae are a strong determining factor regarding whether a plant can survive in its environment.[23] Studies have also shown evidence that "introduced plant species can modify microbial communities in the soil surrounding not only their own roots, but also the roots of neighboring plants, thereby altering competitive interactions among the plant species".[23] This may be a key invasive trait for Oriental bittersweet, as it allows the plant to negatively affect surrounding plant life by altering their underground symbiotic microbial relationships.[23] However, further experimentation is necessary to determine whether this organism employs this trait as an invasive strategy.

Competitive interactions

One of Oriental bittersweet's invasive characteristics is its effective utilization of energy to increase plant height, thus giving it a competitive advantage over similar plants. A study conducted in 2006 showed that, in comparison to its congener American bittersweet, Oriental bittersweet had increased height, increased aboveground biomass, and increased total leaf mass.[20] This is not to say that Oriental bittersweet outperformed American bittersweet in all criteria: in comparison to Oriental bittersweet, "American bittersweet had increased stem diameter, single leaf area, and leaf mass to stem mass ratio", suggestive that American bittersweet focused growth on ulterior portions of the plant rather than plant characteristics emphasized by Oriental bittersweet such as stem length.[20] This is significant as height plays a major role in allowing Oriental bittersweet to outcompete surrounding vegetation.[20] Focusing growth on stem length allows it to be in a strong position to absorb light, while also negatively impacting surrounding plant life by creating shade-like conditions.

The species' vine-like morphology has also been shown to have negative effects on surrounding plant life. For example, evidence suggests that this morphological characteristic facilitates its ability to girdle nearby trees, creating an overall negative effect on the trees such as making them more susceptible to ice damage or damaging branches due to the weight of the plant.[24] Additionally, studies have suggested that Oriental bittersweet is capable of siphoning away nutrients from surrounding plants. The study found this to occur in a variety of environments, suggestive of both the plant's increased relative plasticity as well as increased nutrient uptake.[21]

One study observed that the presence of Oriental bittersweet increases the alkalinity of the surrounding soil, a characteristic of many successful invasive plant species.[24] This alters the availability of essential nutrients and hinders the nutrient uptake ability of native plants. Though the relationship between Oriental bittersweet and the alkalinity of the soil is consistent, there are a number of proposed mechanisms for this observation. The plant's significant above-ground biomass demands the preferential uptake of nitrate over ammonia, leading to soil nitrification. It also has a high cation-exchange capacity, which also supports the larger biomass. Either of these functions could explain the increased alkalinity, but further experimentation is needed to pinpoint the exact mechanism.[24]

Hybridization

Another major threat posed by Oriental bittersweet is hybridization with American bittersweet. Hybridization occurs readily between American bittersweet females and Oriental bittersweet males, though the opposite is known to occur to a lesser extent. The resulting hybrid species is fully capable of reproduction.[25] In theory, if the Oriental bittersweet invasion continues to worsen, widespread hybridization could genetically disrupt the entire American bittersweet population, possibly rendering it extinct.[15]

Management

To minimize the effects of Oriental bittersweet's invasion into North American habitats, its growth and dispersal must be tightly managed. Early detection is essential for successful conservation efforts. To reduce further growth and dispersal, above-ground vegetation is cut and any foliage is sprayed with triclopyr, a common herbicide. Glyphosate is another chemical method of control. These two herbicides are usually sprayed directly on the plants in late fall to prevent other plants from being targeted. These steps must be repeated annually, or whenever regrowth is observed.[26] Triclopyr is non-toxic to most animal and insect species and slightly toxic to some species of fish, but it has a half-life of less than a day in water, making it safe and effective for field use.[26][27] Mechanical methods have also been used, but they are not as effective due to the difficulty of completely removing the root.[28] There is also no biological control agent available in helping control this species.[29] Mechanical and chemical methods are being used, but they are only temporarily fixing the situation.

Phytochemicals

Bicelaphanol A is a neuroprotective dimeric-trinorditerpene isolated from the bark of Celastrus orbiculatus.[30]

Uses

Despite the modest toxicity of its fruit, some livestock browse on the leaves without effect. Its vines, which are durable and tough, are a good source of weaving material for baskets. The fibrous inner bark can be used to make strong cordage.

References

- ↑ Hou, D. (1955). "A revision of the genus Celastrus". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. Missouri Botanical Garden Press. 42 (3): 215–302. doi:10.2307/2394657. JSTOR 2394657.

- ↑ Lee, Sangtae; Chang, Kae Sun, eds. (2015). English Names for Korean Native Plants (PDF). Pocheon: Korea National Arboretum. p. 402. ISBN 978-89-97450-98-5. Retrieved 15 March 2019 – via Korea Forest Service.

- 1 2 Weeks, Sally S.; Weeks, Harmon P. (Jr.) (2011). Shrubs and woody vines of Indiana and the Midwest: Identification, wildlife values, and landscaping use. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. p. 392. ISBN 9781557536105.

- 1 2 3 Czarapata, Elizabeth J. (2005). Invasive plants of the upper Midwest: An illustrated guide to their identification and control. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 45. ISBN 9780299210540.

- ↑ Zhang, Zhixiang; Funston, Michele. "Celastrus orbiculatus". Flora of China. Vol. 11 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- ↑ "Celastrus orbiculatus – Oriental Bittersweet Vine". Conservation New England. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- ↑ "Celastrus orbiculatus". County-level distribution map from the North American Plant Atlas (NAPA). Biota of North America Program (BONAP). 2014.

- ↑ White, Orland E.; Wray M. Bowden (1947). "Oriental and American Bittersweet Hybrids". Journal of Heredity. 38 (4): 125–128. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a105705. PMID 20242535.

- ↑ Uva, Richard H.; Neal, Joseph C.; Ditomaso, Joseph M. (1997). Weeds of The Northeast. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 336–337.

- ↑ Hutchison, Max (1990). "Vegetation Management Guideline: Round-leaved bittersweet". Vegetation Management Manual. Illinois Natural History Survey. Archived from the original on 7 September 2005.

- ↑ Kurtz, Cassandra M. (2018). An Assessment of Oriental Bittersweet in Northern U.S. Forests. Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ↑ Archana Pande; Carol L. Williams; Christopher L. Lant; David J. Gibson. "Using map algebra to determine the mesoscale distribution of invasive plants: the case of Celastrus orbiculatus in Southern Illinois, USA" (PDF). Biol Invasions:2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2010.

- ↑ "Celastrus orbiculatus Hermaphrodite Group". rhs.org. Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- 1 2 McNab, W. H.; Loftis, D. L. (2002). "Probability of occurrence and habitat features for oriental bittersweet in an oak forest in the southern Appalachian mountains, USA". Forest Ecology and Management. 155 (1–3): 45–54. doi:10.1016/S0378-1127(01)00546-1.

- 1 2 Jones, Chad C. (2012). "Challenges in predicting the future distributions of invasive plant species". Forest Ecology and Management. 284: 69–77. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2012.07.024.

- ↑ Albright, Thomas P.; Anderson, Dean P.; Keuler, Nicholas S.; Pearson, Scott M.; Turner, Monica G. (2009). "The spatial legacy of introduction:Celastrus orbiculatusin the southern Appalachians, USA". Journal of Applied Ecology. 46 (6): 1229–1238. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2009.01707.x.

- 1 2 USDA, NRCS (n.d.). "Celastrus orbiculatus". The PLANTS Database (plants.usda.gov). Greensboro, North Carolina: National Plant Data Team.

- ↑ Greenberg, C. H.; Smith, L. M.; Levey, D. J. (2001). "Fruit fate, seed germination and growth of an invasive vine- an experimental test of 'sit and wait' strategy". Biological Invasions. 3 (4): 364–372. doi:10.1023/A:1015857721486. S2CID 6742817.

- 1 2 3 4 Ellsworth, J.W.; Harrington, R.A.; Fownes, J.H (2004). "Survival, growth and gas exchange of Celastrus orbiculatus seedlings in sun and shade". American Midland Naturalist. 151 (2): 233–240. doi:10.1674/0003-0031(2004)151[0233:SGAGEO]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 3566741. S2CID 85822380.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Leicht SA, Silander JA (July 2006). "Differential responses of invasive Celastrus orbiculatus (Celastraceae) and native C. scandens to changes in light quality". Am. J. Bot. 93 (7): 972–7. doi:10.3732/ajb.93.7.972. PMID 21642161.

- 1 2 3 Leicht-Young, Stacey A.; Pavlovic, Noel B.; Grundel, Ralph; Frohnapple, Krystalynn J. (2007). "Distinguishing Native (Celastrus Scandens L.) and Invasive (C. Orbiculatus Thunb.) Bittersweet Species Using Morphological Characteristics". The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society. 134 (4): 441–50. doi:10.3159/07-RA-028.1. JSTOR 20063940. S2CID 86456782.

- 1 2 3 Ibáñez, Inés; Silander, John A.; Wilson, Adam M.; Lafleur, Nancy; Tanaka, Nobuyuki; Tsuyama, Ikutaro (2009). "Multivariate forecasts of potential distributions of invasive plant species". Ecological Applications. 19 (2): 359–75. doi:10.1890/07-2095.1. PMID 19323195.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lett, Carly N.; Dewald, Laura E.; Horton, Jonathan (2011). "Mycorrhizae and soil phosphorus affect growth of Celastrus orbiculatus". Biological Invasions. 13 (10): 2339. doi:10.1007/s10530-011-0046-3. S2CID 22309836.

- 1 2 3 Leicht-Young, Stacey A.; O'Donnell, Hillary; Latimer, Andrew M.; Silander, John A. (2009). "Effects of an Invasive Plant Species, Celastrus orbiculatus, on Soil Composition and Processes". The American Midland Naturalist. 161 (2): 219. doi:10.1674/0003-0031-161.2.219. S2CID 12833005.

- ↑ Pavlovic, N. B.; Young, S. L. (2007). "Distinguishing an alien invasive vine from the native congener: morphology, genetics, and hybridization" (PDF). United States Geological Survey, Ecosystem Health and Restoration Branch.

- 1 2 Pavlovic, N. Leicht-Young, S., Morford, D, & Mulcorney, N. (2011). "To Burn or Not to Burn Oriental Bittersweet: A Fire Manager's Conundrum" (PDF). United States Geological Survey, Lake Michigan Ecological Research Station, Great Lakes Science Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Ganapathy, Carissa (1997). "Environmental Fate of Triclopyr" (PDF). Environmental Monitoring and Pest Management Branch, Department of Pesticide Regulation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2009. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ↑ Swearingen, J., Reshetiloff, K., Slattery B., & Zwicker, S (2002). "Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas". Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas. National Park Service and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. p. 82.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Dryer, Glenn D. (2003). "Oriental Bittersweet: Element Stewardship Abstract". Wildland Weeds Management & Research Program, Weeds on the Web. Archived from the original on 23 October 2008.

- ↑ Ly, Wang; J, Wu; Z, Yang; Xj, Wang; Y, Fu; Sz, Liu; Hm, Wang; Wl, Zhu; Hy, Zhang (26 April 2013). "(M)- and (P)-bicelaphanol A, dimeric trinorditerpenes with promising neuroprotective activity from Celastrus orbiculatus". Journal of Natural Products. 76 (4): 745–9. doi:10.1021/np3008182. PMID 23421714. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

External links

- Species Profile – Oriental Bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus), National Invasive Species Information Center, United States National Agricultural Library. Lists general information and resources for Oriental Bittersweet.