Pungmul (Korean: 풍물; Hanja: 風物; IPA: [pʰuːŋmul]) is a Korean folk music tradition that includes drumming, dancing, and singing. Most performances are outside, with dozens of players all in constant motion. Pungmul is rooted in the dure (collective labor) farming culture. It was originally played as part of farm work, on rural holidays, at other village community-building events, and to accompany shamanistic rituals, mask dance dramas, and other types of performance. During the late 1960s and 1970s it expanded in meaning and was actively used in political protest during the pro-democracy movement, although today it is most often seen as a performing art. Based on 1980s research, this kind of music was extensively studied in Chindo Island.[1]

Older scholars often describe this tradition as nongak (Korean: [noŋak]), a term meaning "farmers' music" whose usage arose during the colonial era (1910–1945). The Cultural Heritage Administration of South Korea uses this term in designating the folk tradition as an Important Intangible Cultural Property. Opposition from performers and scholars toward its usage grew in the 1980s because colonial authorities attempted to limit the activity to farmers in order to suppress its use and meaning among the colonized. It is also known by many synonymous names throughout the peninsula.

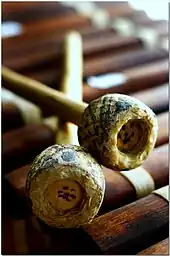

Drumming is the central element of pungmul. Each group is led by a kkwaenggwari (RR- ggwaenggwari) (small handheld gong) player, and includes at least one person playing janggu (hourglass drum), one person playing buk (barrel drum), and one person playing jing (gong). Wind instruments (taepyeongso, also known as hojeok, senap, or nalari) sometimes play along with the drummers.

Pungmul was added to the UNESCO intangible cultural heritage list as "Joseonjok Nongak" by China in 2009 and South Korea in November 2014.[2]

Classification

Pungmul was first recognized as an Important Intangible Cultural Property in 1966 under the title nongak sipicha (농악십이차, "twelve movements of farmers' music"). The designation was changed to simply nongak in the 1980s in order to accommodate regional variations.[3] The Cultural Heritage Administration currently recognizes five regional styles of the tradition, each named for its center of activity, under Important Intangible Cultural Property no. 11: Jinju Samcheonpo nongak, from South Gyeongsang province (designated in 1966); Pyeongtaek nongak, from Gyeonggi province (1985); Iri nongak, from North Jeolla province (1985); Gangneung nongak, from Gangwon province (1985); and Imsil Pilbong nongak from North Jeolla province (1988). Each style is unique in its approach toward rhythms, costuming, instrumentation, and performance philosophy: Jinju Samcheonpo for yeongnam (영남), Pyeongtaek for utdari (웃다리), Iri for honam udo (호남우도), Gangneung for yeongdong (영동), and Imsil Pilbong for honam jwado (호남좌도).[4]

Most scholarly works on pungmul focus on the two distinct styles present in the Honam region encompassing the two Jeolla provinces.[5] In this region, the designations jwado (left) for Imsil Pilbong and udo (right) for Iri are determined according to geomantic principles. Looking southward from the "center" (Seoul, the capital), udo indicates "right", and jwado indicates "left".[4] Comparative studies between the two styles brought about the development of stereotypes among professional groups. Honam jwado became known for its varying formations and rapid rhythmic patterns, while honam udo was generally seen as having slow but graceful rhythmic patterns.[6]

History

Early development

Suppression and unrest

During the Joseon dynasty, this folk tradition was the primary mode of musical expression for a majority of the population.[7] Many scholars and performers today claim that the term nongak (농악; 農樂) was introduced during the Japanese colonization era in order to suppress its broad use and meaning among the Korean population.[8]

Revival

True public support for pungmul improved little in the decade following its recognition and financial backing from the government. There was a lack of interest among Koreans who abandoned their traditional customs after moving to the cities. This phenomenon was coupled with the introduction of Western-style concert halls and the growing popularity of Western classical and popular music.[9]

In 1977, prominent architect Kim Swoo Geun designed the Konggansarang (공간사랑), a performance hall for traditional Korean music and dance located in the capital, and invited artists and scholars to organize its events.[10] During the performance center's first recital in February 1978, a group of four men led by Kim Duk-soo and Kim Yong-bae, both descendants of namsadang troupe members, performed an impromptu arrangement of Pyeongtaek (utdari) pungmul with each of its four core instruments. Unlike traditional pungmul, this performance was conducted in a seated position facing the audience and demonstrated a variety of rhythms with great flexibility. It was well received by audience members, and a second performance was soon held three months later. Folklorist Sim U-seong, who introduced both men to the Konggansarang club, named the group SamulNori (사물놀이; 四物놀이), meaning "playing of four objects".[11] Samul nori eventually came to denote an entire genre as training institutes and ensembles were established throughout South Korea and Japan.[12] Usage of the term nongak was retained in order to distinguish traditional pungmul from this new staged and urbanized form.[13]

Components

Instruments

In general, 5 major instruments are used for playing Pungmul: kkwaenggwari (RR- ggwaenggwari) (small handheld gong), janggu (hourglass drum), buk (barrel drum), and jing (gong) and sogo.

They all require a different style to play and have their own unique sounds.

The first person of each group to play instruments is called 'sue' or 'sang'. (like 'sang soe'(refers to the one who plays kkwaenggwari), 'sue janggu(same as sang janggu), 'sue buk ', 'sue bukku(who play with sogo)')

Dance

In Pungmul, dance elements further deepen the artistic and aesthetic characteristics of Pungmul as an integrated genre.[14]

Pungmul dance does not deviate from the interrelationship and balance with the elements that make up the Pungmul but also harmonizes closely with music.

The dance has a system of individual body structure, such as Witt-Noleum (윗놀음, upper performance) and Bal-Noleum(발놀음, footwork), and a system of pictorial expression in which individuals become objects to complete a group.

Divide according to the form of the dance and the composition of the personnel.[15]

- Group dance (군무[群舞]) : Jinpuri (진풀이, a variety of formations are presented during the performance)

- Solitary dance (독무[獨舞]) : Sangsoe Noleum (상쇠놀음, lead small gong player's solo performance), Sangmonori (상모놀이, hat-streamer twirling performance), Suljanggu Noleum (hourglass-shaped drum performance), Sogo Noleum(소고놀음, small drum with handle performance)

- Japsaek dance (잡색[雜色, lit. mixed colors]) : A member of the Pungmul troupe dressed as a certain character who acts out various skits. All expressions are the result of role-based self-analysis.

Costuming

Following the drummers are dancers, who often play the sogo (a small drum without enough resonance to contribute to the soundscape significantly) and tend to have more elaborate—even acrobatic—choreography, particularly if the sogo-wielding dancers also manipulate the sangmo ribbon-hats. In some regional pungmul types, japsaek (actors) dressed as caricatures of traditional village roles wander around to engage spectators, blurring the boundary between performers and audience. Minyo (folksongs) and chants are sometimes included in pungmul, and audience members enthusiastically sing and dance along. Most minyo are set to drum beats in one of a few jangdan (rhythmic patterns) that are common to pungmul, sanjo, p'ansori (RR-pansori), and other traditional Korean musical genres.

Pungmul performers wear a variety of colorful costumes. A flowery version of the Buddhist gokkal is the most common head-dress. In an advanced troupe all performers may wear sangmo, which are hats with long ribbon attached to them that players can spin and flip in intricate patterns powered by knee bends.

Formations

International exposure

Pungmul is played in several international communities, especially by the Koreans living abroad.

Some dancing activities associated with pungmul performed by the ethnic Koreans living in China, known as the "farmer's dance of ethnic Korean" (조선족 농악 무; 朝鮮族農樂舞; Chosŏnjok nongak-mu), were submitted as a cultural heritage to UNESCO.

Pungmul also has been performed by the numerous Korean American communities in the United States, including Oakland, Los Angeles, Chicago, New York City, and Baltimore.[16]

College-based groups also exist at the University of California (Berkeley, Los Angeles, Davis, San Diego, Santa Barbara, Irvine), University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Stony Brook University, Columbia University, New York University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard University, Yale University, the University of Chicago, the University of Pennsylvania, Cornell University, California Institute of Technology, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, University of Buffalo, Binghamton University, Syracuse University, Stanford University, The University of Toronto, Brown University, University of Oxford, etc.,[16] Far Eastern Federal University

Development of Pungmul in America

First phase (1985 - 1989)

P'ungmul's history in the United States is intimately linked to the history of Korean American activism. Numerous founders of these organizations were active in or sympathized with Korean political conflicts. It is critical to note that all of these Korean expressive styles were prevalent throughout the 1970s and 1980s Minjung Munhwa movement that swept South Korean college campuses. Many of the early p'ungmul organizations either originated as a cultural division of a larger organizational (usually political) or became part of one, shortly after formation. In 1985, Binari in New York was established and Sori, formed on the University of California in Berkeley. Il-kwa-Nori of the Korean American Resource and Cultural Center in Chicago, also an affiliate of NAKASEC, formed in 1988. Shinmyŏngpae of the communal organization Uri Munhwa Chatkihwe in 1990.[17]

In the 1970s and 1980s, a few Koreans stayed in the US for long periods of time to assist create p'ungmul organizations and spread its teachings. Kim Bong Jun, a Korean artist noted for his folk-inspired paintings and prints, was one such people. Many people were forced to reconsider their participation in the Korean-American connection due to issues like reunification and knowledge about the Kwangju Uprising.

Second phase (1990 - Present)

Yi Jong-hun, a Korean minister who visited the United States in 1990 and 1991, is another figure seen as important by many long-time p'ungmul practitioners. Yi Jong-hun paid visits to Los Angeles, New York City, and KYCC in Oakland during his tour. He was involved in the formation of the Kutkori group at Harvard. He also provided reading and teaching materials on Pungmul, Minyo, and Movement Songs.[17] A normal college p'ungmul group has between 15-20 members on average, while some organizations have persisted with less than 10 and as many as 30 to 35 members. Hanoolim[18] (University of California/Los Angeles), Karakmadang (University of Illinois), Hansori (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), NyuRi (New York University), and Loose Roots (University of Chicago) are just a few of the early 1990s groups. Other forms of special-interest clubs have emerged in the United States, bringing more variety to the community of p'ungmul students. Groups have been founded by and for Korean adoptees and activists as well as seniors, kids, Catholic Church members, and people in their mid-thirties and forties, to name just a few.[17]

See also

- Important Intangible Cultural Properties of Korea

- Korean dance

- Traditional music of Korea

- Namsadang, itinerant performance troupe having pungmul in its repertoire

- Samul nori, traditional percussion genre derived from multiple pungmul styles

- Pung cholom, a similar dance from Manipur, India

References

Citations

- ↑ Howard, Keith (1989) Bands, Songs and Shamanistic Rituals: Folk Music in Korean Society. Seoul: Royal Asiatic Society. (2nd ed 1990)

- ↑ "'Nongak' added to UNESCO list". Korea.net. 2014-11-28. Retrieved 2014-11-28.

- ↑ Hesselink 2006, p. 10

- 1 2 Hesselink 2006, p. 11

- ↑ Park 2000, p. 65

- ↑ Park 2000, p. 66

- ↑ Hesselink 2006, p. 2

- ↑ Hesselink 2006, p. 15

- ↑ Hesselink 2004, pp. 408–409

- ↑ Park 2000, p. 177

- ↑ Park 2000, p. 178

- ↑ Hesselink 2004, pp. 410

- ↑ Park 2000, p. 25

- ↑ Ok-kyeong, Yang (2011). ""In Pungmulgut, functions and aesthetic affects of the dance-Based on the actual of Pilbongnongak-."". Journal of Korean Dance History. 24: 157–180.

- ↑ 국립민속박물관. "Jinpuri". Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2019-03-15.

- 1 2 "Pungmul in the US". US Pungmul. 23 May 2011. Retrieved 2014-11-28.

- 1 2 3 Kwon, D. L (2001). "The Roots and Routes of Pungmul in the United States". Music and Culture: 39–56.

- ↑ "Hanoolim: Korean Cultural Awareness Group at UCLA".

Bibliography

- Bussell, Jennifer L. (2 May 1997). A Life of Sound: Korean Farming Music and its Journey to Modernity (BA essay). University of Chicago. Archived from the original on 3 July 2007.

- Hesselink, Nathan (1999). "Kim Inu's 'P'ungmulgut and Communal Spirit': Edited and Translated with an Introduction and Commentary". Asian Music. Society for Asian Music. 31 (1): 1–34. doi:10.2307/834278. ISSN 0044-9202. JSTOR 834278.

- Hesselink, Nathan (2004). "Samul nori as Traditional: Preservation and Innovation in a South Korean Contemporary Percussion Genre". Ethnomusicology. Society for Ethnomusicology. 48 (3): 405–439. ISSN 0014-1836. JSTOR 30046287.

- Hesselink, Nathan (2006). P'ungmul: South Korean Drumming and Dance. Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-33095-2.

- Hesselink, Nathan (2007). "Taking Culture Seriously: Democratic Music and Its Transformative Potential in South Korea". The World of Music. University of Bamberg. 49 (3): 75–106. ISSN 0043-8774. JSTOR 41699789.

- Hesselink, Nathan (June 2009). "'Yŏngdong Nongak': Mountains, Music, and the Samulnori Canon". Acta Koreana. Academia Koreana. 12 (1): 1–26. doi:10.18399/acta.2009.12.1.001. ISSN 1520-7412.

- Kwon, Donna (2001). "미국에서의 풍물: 그 뿌리와 여정" [The Roots and Routes of P'ungmul in the United States]. Eumak-gwa Munhwa 음악과 문화 [Music and Culture] (in Korean). Korean Society for World Music. 5: 39–65. ISSN 1229-5930. OCLC 5588715083.

- Park, Shingil (2000). Negotiating Identities in a Performance Genre: The Case of P'ungmul and Samulnori in Contemporary Seoul (PhD thesis). University of Pittsburgh. ISBN 978-0-599-79965-3. OCLC 53209871.

External links

- P'ungmul nori at the Virtual Instrument Museum of Wesleyan University

- Poongmul.com, a network of pungmul groups in the United States

- sdpungmul.org, Pungmul school in San Diego, CA, United States

- Pungmul on YouTube, very well made video from Bucheon, Korea