| Ningishzida 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒄑𒍣𒁕 | |

|---|---|

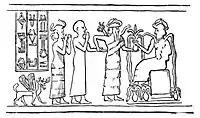

Ningishzida, with snakes emanating from his shoulders, on a relief of Gudea, c. 2000 BCE | |

| Major cult center | Gishbanda, Lagash |

| Symbol | Snake, mushussu |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Ninazu and Ningirida |

| Siblings | Amashilama and Labarshilama |

| Consort | Geshtinanna, Azimua, Ekurritum |

Ningishzida (Sumerian: 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒄑𒍣𒁕 DNIN-G̃IŠ-ZID-DA, possible meaning "Lord [of the] Good Tree") was a Mesopotamian deity of vegetation, the underworld and sometimes war. He was commonly associated with snakes. Like Dumuzi, he was believed to spend a part of the year in the land of the dead. He also shared many of his functions with his father Ninazu.

In myths he usually appears in an underworld setting, though in the myth of Adapa he is instead described as one of the doorkeepers of the sky god Anu.

Name

Thorkild Jacobsen proposed that the Sumerian name Ningishzida can be explained as "lord of the good tree." This translation is still accepted by other Assyriologists today.[1][2] Various syllabic spellings are known, including dNi-gi-si-da, dNin-nigi-si-da, dNin-ki-zi-da and dNin-gi-iz-zi-da.[1]

While "nin" can be translated as "lady" in some contexts, it was grammatically neutral in Sumerian and can be found in the names of many deities, both male (Ningishzida, Ninazu, Ninurta, etc.) and female (Ninlil, Ninkasi etc.).[3]

Ningishzida could also be called Gishbanda ("little tree").[4]

Functions

Ningishzida's titles connect him to plants and agriculture.[4] He was frequently mentioned in connection with grass, which he was believed to provide for domestic animals.[5] The death of vegetation was associated with his annual travel to the underworld.[6] The "tree" in his name might be vine according to some Assyriologists, including Wilfred G. Lambert, and an association between him and alcoholic beverages (specifically wine) is well attested, for example one text mentions him alongside the beer goddess Ninkasi, while one of his titles was "lord of the innkeepers."[6]

Like his father Ninazu, he was also associated with snakes, including the mythical mushussu, ushumgal and bashmu and in one case Nirah.[6] He was also an underworld god, and in this role was known as the "chair bearer (or chamberlain) of the underworld."[7] Frans Wiggermann on the basis of these similarities considers him and his father to be members of the group of "Transtigridian snake gods," who according to him shared a connection with the underworld, justice, vegetation and snakes.[8] A further similarity between Ningishzida and his father was his occasional role as a warrior god, associated with victory (and as a result with the goddess Irnina, the personification of it).[7] However, not all of their functions overlapped, as unlike Ninazu, Ningishzida never appears in the role of a divine healer.[4]

According to Frans Wiggermann, Ningishzida's diverse functions can be considered different aspects of his perception as a "reliable god," well attested in Mesopotamian texts.[7]

The constellation Hydra could serve as his symbol, though it was also associated with Ishtaran and Ereshkigal.[9]

Worship

The worship of Ningishzida is attested for the first time in the Early Dynastic III period.[10] His main cult center was Gishbanda,[2] likely a rural settlement[11] located somewhere between Lagash and Ur.[12] His main temple was known simply as E-Gishbanda,[13] "house of Gishbanda," and it was commonly listed alongside the main temple of his father Ninazu, E-Gidda.[14]

He also had a temple in Lagash, the E-badbarra, "house, outer wall."[15] Yet another one was built in Girsu by Gudea, though its name is unknown.[16] This ruler considered him to be his personal god.[17] In one of his inscriptions, Ningishzida is named a participant in a festival celebrating the marriage between Ningirsu and Bau.[18] In another, he is credited with helping Gudea with building new temples.[19] In a later incantation which served as a part of temple renovation rituals, referred to as The First Brick by Wilfred G. Lambert,[20] Ningishzida is mentioned in a similar context alongside many other deities, such as Lisin, Gukishbanda, Kulla, Lahar and Ninshar.[21]

In Ur he was worshiped in the temple E-niggina, "house of truth," known from an inscription of Sin-Iqisham stating it was rebuilt during his reign.[22] He is attested in offering lists from that city from the Ur III and Old Babylonian periods, sometimes alongside Ningubalaga.[23] In later sources, up to the reign of the Persian emperor Darius I, he sometimes appears in theophoric names, likely due to association with Ninazu, who retained a degree of relevance in the local pantheon.[24] Much like in the case of his father, some of them used the dialectical Emesal form of his name, Umun-muzida.[25] It is presumed that the cause of this was the role lamentation priests, who traditionally memorized Emesal compositions, played in the preservation of cults of underworld gods in Ur.[26]

As early as in the Ur III period Ningishzida was introduced to Uruk.[27] He was also present in Kamada, possibly located nearby, as attested in documents from the reign of Sin-kashid.[27] During the reign of Marduk-apla-iddina I he was worshiped in a chapel in the Eanna complex, originally built during the reign of Old Babylonian king Anam.[16] He continued to appear in theophoric names from neo-Assyrian, neo-Babylonian and Hellenistic Uruk, though only uncommonly.[28]

Ningishzida was also worshiped in Isin, which was primarily the cult center of the medicine goddess Ninisina, but had multiple houses of worship dedicated to underworld deities as well, with the other examples being Nergal, Ugur, and an otherwise unknown most likely chthonic goddess Lakupittu who according to Andrew R. George was likely the tutelary deity of Lagaba near Kutha.[13]

Further locations where he was worshiped include Umma, Larsa, Kuara, Nippur, Babylon, Eshnunna and Kisurra.[29] From most of them evidence is only available from the Ur III or Old Babylonian periods, though in Babylon he still had a small cult site in Esagil in the neo-Babylonian period.[29] A single object inscribed with a dedication to Ningishzida is also known from Susa, though it might have been brought there as booty from some Mesopotamian polity.[10]

Associations with other deities

Ningishzida was the son of Ninazu and his wife Ningiridda.[1] One of the only references to goddesses breastfeeding in Mesopotamian literature is a description of Ningirida and her son.[30] His sisters were Amashilama and Labarshilama.[29]

References to Ningishzida as a "scion" of Anu are probably meant to indicate the belief in a line consisting out of Anu, Enlil, Ninazu and finally Ningishzida, rather than the existence of an alternate tradition where he was the son of the sky god.[1]

Multiple traditions existed regarding the identity of Ningishzida's wife, with the god list An = Anum listing two, Azimua (elsewhere also called Ninazimua[31]) and Ekurritum (not attested in such a role anywhere else[4]), while other sources favor Geshtinanna, identified with Belet-Seri.[13] However, Azimua shared Gesthinanna's role as an underworld scribe,[1]and her name could also function as a title of Geshtinanna, attested in contexts where she was identified as Ningishzida's wife.[32] At the same time, Belet-Seri could also function as an epithet of Ashratum, the wife of Amurru, or of her Sumerian counterpart Gubarra, in at least one case leading to conflation of Amurru and Ningishzida and to an association between the former and Azimua and Ekurritum.[33] In one case Ekurritum was simply identified as an alternate name of Ashratum as well.[4] The tradition in which Gesthinanna was Ningishzida's wife had its origin in Lagash, and in seals from that city she is sometimes depicted alongside a mushussu, symbol of her husband, to indicate they're a couple.[34] One inscription of Gudea refers to her as Ningishzida's "beloved wife."[35]

Ningishzida's sukkal was Alla,[4] a minor underworld god,[36] depicted as a bald beardess man, without the horned crown associated with divinity.[4] Wilfred G. Lambert notes that he was most likely another Dumuzi-like deity whose temporary death was described in laments.[37] He is also attested in lists of so-called "seven conquered Enlils,"[38] deities associated with Enmesharra.[39] Another deity also identified as Ningishzida's sukkal was Ipahum or Ippu, a viper god, also known as the sukkal of his father Ninazu.[4] Other deities who belonged to his court include Gishbandagirizal, Lugalsaparku, Lugalshude, Namengarshudu, Usheg[29] and Irnina.[4]

Ningishzida could be associated with Dumuzi, on account of their shared character as dying gods of vegetation.[40] A lamentation text known as "In the Desert by the Early Grass" lists both of them among the mourned deities.[6] The absence of both of them was believed to take place each year between mid-summer and mid-winter.[41] The association is also present in astrological treatises.[10] Some lamentations go as far as regarding Ningishzida and Dumuzi as one and the same.[35] As dwellers of the underworld, both of them could be on occasion associated with Gilgamesh as well.[42]

Another temporarily dying god Ningishzida could be associated with was Damu.[43]

In some inscriptions of Gudea, Ningishzida was associated with Ningirsu, with one of them mentioning that he was tasked with delivering gifts for the latter's wife Bau.[18] Such a role was customarily associated with trusted associates and close friends in ancient Mesopotamian culture, indicating that despite originally being unrelated, these two gods were envisioned as close to each other by Gudea.[18]

Mythology

In the Middle Babylonian myth of Adapa, Ningishzida is one of the two doorkeepers of Anu's celestial palace, alongside Dumuzi.[6] This myth appears to indicate that these two gods are present in heaven rather than underworld when they are dead, even though other Sumerian and Akkadian myths describe Ningishzida's journey to the underworld.[6] Little is known about the circumstances of his annual return, though one text indicates an unidentified son of Ereshkigal was responsible for ordering it.[6]

A reference to Ningishzida is present in the Epic of Gilgamesh.[44] The eponymous hero's mother Ninsun mentions to Shamash that she is aware her son is destined to "dwell in the land of no return" with him.[44] In another Gilgamesh myth, Death of Gilgamesh, the hero is promised a position in the underworld equal to that of Ningishzida.[45]

Gallery

Ningishzida on the libation vase of Gudea, circa 2100 BCE

Ningishzida on the libation vase of Gudea, circa 2100 BCE The "libation vase of Gudea" with the dragon Mušḫuššu, dedicated to Ningishzida, circa 2100 BCE (short chronology). The caduceus-like symbol (right) is interpreted as a representation of the god himself. Inscription: "To the god Ningiszida, his god, Gudea, Ensi (governor) of Lagash, for the prolongation of his life, has dedicated this"

The "libation vase of Gudea" with the dragon Mušḫuššu, dedicated to Ningishzida, circa 2100 BCE (short chronology). The caduceus-like symbol (right) is interpreted as a representation of the god himself. Inscription: "To the god Ningiszida, his god, Gudea, Ensi (governor) of Lagash, for the prolongation of his life, has dedicated this" The name Ningishzida inscribed on a statue of Ur-Ningirsu.

The name Ningishzida inscribed on a statue of Ur-Ningirsu. Seal of Gudea depicting him being led by Ningishzida (figure with snakes emerging from his shoulders)

Seal of Gudea depicting him being led by Ningishzida (figure with snakes emerging from his shoulders) Detail, headless statue dedicated to Ningishzida, 2600-2370 BCE. Iraq Museum.

Detail, headless statue dedicated to Ningishzida, 2600-2370 BCE. Iraq Museum.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wiggermann 1998, p. 368.

- 1 2 Vacín 2011, p. 253.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, pp. 6–7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Wiggermann 1998, p. 369.

- ↑ Wiggermann 1998, pp. 369–370.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Wiggermann 1998, p. 370.

- 1 2 3 Wiggermann 1998, p. 371.

- ↑ Wiggermann 1997, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Vacín 2011, pp. 256–257.

- 1 2 3 Wiggermann 1998, p. 372.

- ↑ Wiggermann 1997, p. 40.

- ↑ Vacín 2011, pp. 253–254.

- 1 2 3 George 1993, p. 37.

- ↑ George 1993, p. 95.

- ↑ George 1993, p. 71.

- 1 2 George 1993, p. 168.

- ↑ Vacín 2011, pp. 258–259.

- 1 2 3 Vacín 2011, p. 261.

- ↑ Vacín 2011, pp. 262–263.

- ↑ Lambert 2013, p. 376.

- ↑ Lambert 2013, p. 381.

- ↑ George 1993, p. 132.

- ↑ Beaulieu 2021, p. 171.

- ↑ Beaulieu 2021, pp. 170–172.

- ↑ Beaulieu 2021, p. 172.

- ↑ Beaulieu 2021, p. 170.

- 1 2 Beaulieu 2003, p. 345.

- ↑ Krul 2018, p. 356.

- 1 2 3 4 Vacín 2011, p. 254.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 144.

- ↑ Krul 2018, p. 357.

- ↑ Lambert 2013, p. 389.

- ↑ George 1993, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, pp. 206–207.

- 1 2 Lambert 2013, p. 388.

- ↑ Lambert 2013, p. 223.

- ↑ Lambert 2013, pp. 223–224.

- ↑ Lambert 2013, p. 212.

- ↑ Lambert 2013, p. 216.

- ↑ Wiggermann 1997, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Wiggermann 1997, p. 41.

- ↑ George 2003, pp. 127–128.

- ↑ Vacín 2011, pp. 254–255.

- 1 2 George 2003, p. 127.

- ↑ George 2003, p. 128.

Bibliography

- Asher-Greve, Julia M.; Westenholz, Joan G. (2013). Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources (PDF). ISBN 978-3-7278-1738-0.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2003). The pantheon of Uruk during the neo-Babylonian period. Leiden Boston: Brill STYX. ISBN 978-90-04-13024-1. OCLC 51944564.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2021). "Remarks on Theophoric Names in the Late Babylonian Archives from Ur". Individuals and Institutions in the Ancient Near East. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9781501514661-006.

- George, Andrew R. (1993). House most high: the temples of ancient Mesopotamia. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-80-3. OCLC 27813103.

- George, Andrew R. (2003). The Babylonian Gilgamesh epic: introduction, critical edition and cuneiform texts. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-814922-0. OCLC 51668477.

- Krul, Julia (2018). "Some Observations on Late Urukean Theophoric Names". Grenzüberschreitungen Studien zur Kulturgeschichte des Alten Orients: Festschrift für Hans Neumann zum 65. Geburtstag am 9. Mai 2018. Münster: Zaphon. ISBN 3-96327-010-1. OCLC 1038056453.

- Lambert, Wilfred G. (2013). Babylonian creation myths. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-861-9. OCLC 861537250.

- Vacín, Luděk (2011). "Gudea and Ninĝišzida: A Ruler and His God". U4 du11-ga-ni sá mu-ni-ib-du11: ancient Near Eastern studies in memory of Blahoslav Hruška. Dresden: Islet. ISBN 978-3-9808466-6-0. OCLC 761844864.

- Wiggermann, Frans A. M. (1997). "Transtigridian Snake Gods". In Finkel, I. L.; Geller, M. J. (eds.). Sumerian Gods and their Representations. ISBN 978-90-56-93005-9.

- Wiggermann, Frans A. M. (1998), "Nin-ĝišzida", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, retrieved 2022-03-20