| Nine bows in hieroglyphs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

psḏt pḏt pesedjet pedjet[1] | |||

The Nine Bows is a visual representation in Ancient Egyptian art of foreigners or others.[2][3] Besides the nine bows, there were no other generic representations of foreigners.[3] Due to its ability to stand in for any nine enemies to Ancient Egypt, the peoples covered by this term changed over time as enemies changed, and there is no true list of the nine bows.[3]

Alternatively, the nine bows may have had a separate or complementary meaning.[3] In Egyptian hieroglyphs, the word 'Nine Bows' is spelled out as a bow and three sets of three vertical lines. The bow, holding the phonic value "pḏ," means "stretch, (be) wide," and the three sets of lines makes the word plural.[3][4] The number nine was used metaphorically to express totality.[2] Using this more literal translation of the hieroglyphs, the nine bows could also refer to endless, innumerable foreign lands or the totality of foreign lands.[2][3]![]()

It is important to note that Ancient Egyptians believed in dualism or that two cosmic forces, order and chaos, governed the universe. While the nine bows stood in for Ancient Egypt's enemies, it is also possible that they stood in for disorder as well.[5]

Symbolism in art

Instances of the nine bows appeared as early as the late predynastic period (3200-3000 BCE). Discovered in Hierakonpolis or Nekhen, here the nine bows were carved on the head of a scepter.[5] As time progressed, the use of the nine bows expanded to other mediums of art.

When in statuette and statue form, it is typical for the nine bows to be displayed underneath feet.[6] The iconography is similar to a biblical text such as Psalm 110:1 “… until I make your enemies your footstool,” meaning the nine bows placement underneath the feet of Pharaohs and other powerful figures, such as a sphinx, were meant to symbolize the enemy being trampled or entirely under control.[6] One such example of the footstool comes from the tomb of Pharaoh-King Tutankhamun. Each time that King Tut stepped on the footstool, he would symbolically be trampling his enemies.[6] Another example, can be seen on the insoles of Pharaoh's sandals.[6] On the sandals, each shoe has eight bows laying horizontally in a vertical line with one another. Four of the bows are at the top of the sandal near the toe, while four are at the heel. Where the arch of the foot would be, there are two foreigners of Ancient Egypt depicted facing outward on each shoe. As with the footstool, whenever the sandals were worn, it would have been as if the enemies of Ancient Egypt were trampled.[6]

Pharaoh Djoser

One of the oldest representations of the nine bows, and the first representation of the nine bows fully developed, is on the seated statue of Pharaoh Djoser. His feet rest upon part of the nine bows, which may have referred to Nubians during his reign because of their use of bows and arrows.[2][7]

Pedestal of Ramses II

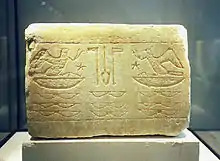

.jpg.webp)

The pedestal of Ramses II was found in Antinoopolis, El-Minya, Egypt. It is rectangular in shape and made of Egyptian alabaster. [5] The engravings found on three sides are carved using Bas-relief, which is indicative of the New Kingdom and Ramses II's reign.[5] Along with the nine bows depicted on top of the pedestal underneath Ramses II's feet, the pedestal also includes engravings of Ramses II's cartouche along with his Horus name and legends of Ramses II's rule.[5]

Gallery of Images

The Bronze Sphinx of Thutmose III, depicting a sphinx reclining over the Nine Bows

The Bronze Sphinx of Thutmose III, depicting a sphinx reclining over the Nine Bows Statue pedestal of Nectanebo II, the Nine Bows carved on the lower half

Statue pedestal of Nectanebo II, the Nine Bows carved on the lower half Fragment of the base of a basalt statue dated to the Late Period, the Nine Bows being beneath the feet of the subject of the statue

Fragment of the base of a basalt statue dated to the Late Period, the Nine Bows being beneath the feet of the subject of the statue_-_275.jpg.webp) Sandals of Tutankhamun, showing foreigners alongside eighth bows and the ninth being the sandal strap

Sandals of Tutankhamun, showing foreigners alongside eighth bows and the ninth being the sandal strap Wall relief of Mut, mortuary temple of Ramses III, Medinet Habu, Theban Necropolis, Egypt

Wall relief of Mut, mortuary temple of Ramses III, Medinet Habu, Theban Necropolis, Egypt

References

- ↑ Middle Egyptian Grammar: The Poetical Stela of Thutmose III: Part I , Dr. Gabor Toth, Rutgers University.

- 1 2 3 4 "Enemies of Civilization: Attitudes toward Foreigners in Ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China", Mu-chou Poo. SUNY Press, Feb 1, 2012. p. 43. Retrieved 7 jan 2017

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tait, John (2003). 'Never Had the Like Occurred': Egypt's view of its past. Great Britain: UCL Press. pp. 155–185. ISBN 9781315423470.

- ↑ Griffith, F. Ll.; Gardiner, Alan H. (November 1927). "Egyptian Grammar, Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 13 (3/4): 279. doi:10.2307/3853984. ISSN 0307-5133. JSTOR 3853984.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Waziry, Ayman (2019). "An Unpublished Pedestal of Ramses II from Antinoopolis with Reference to the Nine Bows". Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology. 6: 14–29. doi:10.14795/j.v6i1.365.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cornelius, Sakkie. "Ancient Egypt and the Other". Scriptura: 322–340.

- ↑ Bestock, Laurel (2017). Violence and power in ancient Egypt : Image and Ideology Before the New Kingdom. Abingdon, United Kingdom: Routledge. p. 149. ISBN 9780367878542.

Sources

- Kevin A. Wilson (2005). The Campaign of Pharaoh Shoshenq I Into Palestine. Mohr Siebeck.