| Night and the City | |

|---|---|

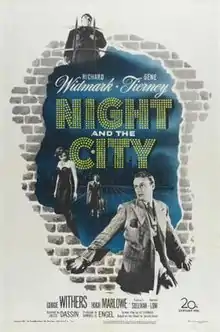

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jules Dassin |

| Written by |

|

| Screenplay by | Jo Eisinger |

| Based on | Night and the City by Gerald Kersh |

| Produced by | Samuel G. Engel |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Max Greene |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Franz Waxman (Benjamin Frankel in the British version) |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 96 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

Night and the City is a 1950 film noir directed by Jules Dassin and starring Richard Widmark, Gene Tierney and Googie Withers.[1] It is based on the novel of the same name by Gerald Kersh. Shot on location in London and at Shepperton Studios, the plot revolves around an ambitious hustler who meets continual failures.

Dassin later confessed that he had never read the novel upon which the film is based. In an interview appearing on The Criterion Collection DVD release, Dassin recalls that the casting of Tierney was in response to a request by Darryl Zanuck, who was concerned that personal problems had rendered the actress "suicidal" and hoped that work would improve her state of mind. The film's British version was five minutes longer, with a more upbeat ending and featuring a completely different film score. Dassin endorsed the American version as closer to his vision.[2]

The film contains a very tough and prolonged fight scene between Stanislaus Zbyszko, a celebrated professional wrestler in real life, and Mike Mazurki, who before becoming an actor was himself a professional wrestler.

Plot

Harry Fabian is an ambitious American hustler and con man on the make in London. He maintains a fractured relationship with the honest Mary Bristol, and with nightclub owner and businessman Phil Nosseross, and with Nosseross's scheming wife, Helen.

While attempting a con at a wrestling match, Fabian witnesses Gregorius, a veteran Greek wrestler, arguing with his son Kristo, who has organised the fight, and who effectively controls all wrestling in London. After denouncing Kristo's event as tasteless exhibitionism that shames the sport's Graeco-Roman traditions, Gregorius leaves with Nikolas, a fellow wrestler.

Fabian catches up with the two and befriends them, thinking that he could host wrestling in London without interference from Kristo if he could persuade Kristo's father to support the enterprise.

Fabian approaches Nosseross and Helen with his proposal, then asks for an investment. Nosseross is incredulous, but at his wife's instigation he offers to provide half of the required £400 if Fabian can match it. Desperate, Fabian asks for money from Figler, a panhandler and unofficial head of an informal society of street criminals; Googin, a forger; and Anna, a Thameside smuggler, but none will help him.

Fabian is eventually approached by Helen Nosseross, who offers the £200 in exchange for getting a licence to continue running her own nightclub, having obtained the money by selling an expensive fur her husband recently bought for her. Fabian agrees, but tricks her by having Googin forge the licence.

Meanwhile, Nosseros is visited by associates of Kristo, who warn him to keep Fabian away from London's wrestling scene. Already suspecting his wife of duplicity, Nosseross neglects to warn Fabian, who proceeds to open his own gym with Gregorius and Nikolas as the stars, and Nosseross as his silent partner.

A furious Kristo visits the gym and discovers that his father is supporting Fabian's endeavour. Meeting with Nosseross, the two plot to kill Fabian, but realise that they can only do so if Gregorius leaves Fabian. Nosseross meets with Fabian and withdraws his backing, suggesting that Fabian gets Nikolas and The Strangler, a showy wrestler favoured by Kristo, into the ring together to keep the business going, knowing that Gregorius would never allow it.

Fabian convinces The Strangler's manager, Mickey Beer, to support the fight, and taunts The Strangler into confronting Gregorius and Nikolas. Gregorius agrees to the fight, convinced by Fabian that it will prove that his traditional style of wrestling is superior. Beer asks Fabian for £200 to cover his fee, so Fabian asks Nosseross for the money. Instead, Nosseross calls Kristo, informing him that The Strangler is in Fabian's gym.

Betrayed, Fabian steals the money from Mary Bristol and returns to the gym. However, The Strangler goads Gregorius into a prolonged and brutal fight, during which Nikolas' wrist is broken.

Gregorius eventually defeats The Strangler in the ring as Kristo arrives, but dies minutes later in his son's arms from exhaustion. Seeing that both his business and protection are lost, Fabian flees.

In revenge for his father's death, Kristo puts a £1,000 bounty on Fabian's head, sending word to all of London's underworld. Fabian is hunted through the night by Kristo's men. Figler attempts to trap Fabian for the reward but he gets away.

Meanwhile, convinced that her licence is authentic, Helen Nosseross leaves her husband, only to discover that the document is a worthless forgery. She returns to Nosseross in desperation, only to discover that he has killed himself because she left him.

Fabian eventually finds shelter at Anna's scow on the Thames, but he is tracked down by Kristo. Mary arrives, and Fabian attempts to redeem himself by shouting to Kristo that Mary has betrayed him, so that she will get the reward. As he runs towards where Kristo is standing on Hammersmith Bridge, he is caught and killed by The Strangler, who throws his body into the river. The Strangler is arrested moments later, and Kristo walks away from the scene. Mary is comforted by her neighbour and close friend Adam Dunne.

Cast

- Richard Widmark as Harry Fabian

- Gene Tierney as Mary Bristol (singing voice dubbed by Maudie Edwards)

- Googie Withers as Helen Nosseross

- Hugh Marlowe as Adam Dunne

- Francis L. Sullivan as Phil Nosseross, Silver Fox Club owner

- Herbert Lom as Kristo

- Aubrey Dexter as Mr Chilk

- Maureen Delany as Anna Siberia/O'Leary

- Stanislaus Zbyszko as Gregorius the Great

- Mike Mazurki as The Strangler

- Ada Reeve as Molly

- Charles Farrell as Mickey Beer

- Ken Richmond as Nikolas of Athens

- Edward Chapman as Hoskins

- James Hayter as Figler

- Gibb McLaughlin as Googin (uncredited)[3]

- Adelaide Hall (scenes cut from the final edit)[4]

Critical reaction

The film has been described as innovative in its lack of sympathetic characters, the deadly punishment of its protagonist (in the American version), and especially its realistic portrayal of triumph by racketeers who are neither slowed nor at all worried by the machinations of law. Critics of the time did not react well; typical were Bosley Crowther's comments in The New York Times:

[Dassin's] evident talent has been spent upon a pointless, trashy yarn, and the best that he has accomplished is a turgid pictorial grotesque...he tried to bluff it with a very poor script—and failed...[the screenplay] is without any real dramatic virtue, reason or valid story-line...little more than a melange of maggoty episodes having to do with the devious endeavors of a cheap London night-club tout to corner the wrestling racket—an ambition in which he fails. And there is only one character in it for whom a decent, respectable person can give a hoot.[5]

The film was first re-evaluated in the 1960s, as film noir became a more esteemed genre, and it has continued to receive laudatory reviews since then. Writing for Slant Magazine, Nick Schager said,

Jules Dassin's 1950 masterpiece was his first movie after being exiled from America for alleged communist politics, and the unpleasant ordeal seems to have infused his work with a newfound resentment and pessimism, as the film—about foolhardy scam-artist Harry Fabian (Richard Widmark) and his ill-advised attempts to become a big shot—brims with anger, anxiousness, and a shocking dose of unadulterated hatred.[6]

In The Village Voice, film critic Michael Atkinson wrote, "... the movie's a moody piece of Wellesian chiaroscuro (shot by Max Greene, né Mutz Greenbaum) and an occasionally discomfiting underworld plunge, particularly when the mob-controlled wrestling milieu explodes into a kidney-punching donnybrook."[7]

In Street with No Name: A History of the Classic American Film Noir, film critic Andrew Dickos acclaims it as one of the seminal noirs of the classical period, writing: "in a perfect fusion of mood and character, Dassin created a work of emotional power and existential drama that stands as a paradigm of noir pathos and despair."

Preservation

The Academy Film Archive preserved Night and the City in 2004.[8]

The British Lion Film Production Disc collection at the British Library includes music from the film soundtrack of Night and the City, upon which Adelaide Hall is featured.[9]

Release

Night and the City was released in the United Kingdom in April 1950.[10]

The film was released as a Region 1 DVD in February 2005 as part of The Criterion Collection and in Region 2 by the BFI in October 2007. Both discs contained the U.S. version only. Criterion issued the film on Blu-ray as a two-disc edition containing both the U.S. and U.K. versions in August 2015. In September 2015, the BFI also released the film on Blu-ray, again containing both versions.

Remake

Night and the City, a 1992 film starring Robert De Niro, was based on the film.

References

- ↑ "The 100 Best Film Noirs of All Time". Paste. 9 August 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- ↑ Night and the City at The Criterion Collection

- ↑ "Gibb McLaughlin".

- ↑ Night and the City - Adelaide Hall - IMDB: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0042788

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley. The New York Times, film review, 10 June 1950. Last accessed: 3 December 2009.

- ↑ Schager, Nick. Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Slant Magazine, DVD review of the film, 16 February 2005. Last accessed: 3 December 2009.

- ↑ Atkinson, Michael. The Village Voice, film review, 25 March 2003. Last accessed: 3 December 2009.

- ↑ "Preserved Projects". Academy Film Archive.

- ↑ The British Library, Euston Road, London: The British Lion Film Production disc collection: Night and the City - 1047X take 1 - 1046X take 7 - 1046X take 8-10: http://explore.bl.uk/primo_library/libweb/action/search.do?fn=search&ct=search&initialSearch=true&mode=Basic&tab=local_tab&indx=11&dum=true&srt=rank&vid=BLVU1&frbg=&tb=t&vl%28freeText0%29=adelaide+hall+night+and+the+city+&scp.scps=scope%3A%28BLCONTENT%29&vl%282084770704UI0%29=any&vl%282084770704UI0%29=title&vl%282084770704UI0%29=any

- ↑ Gifford 2001, p. 570.

Bibliography

- Gifford, Denis (2001) [1973]. The British Film Catalogue. Vol. 1 (3 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-57958-171-8.

- Harry Tomicek: Der Wahnsinnsläufer. Night and The City. von Jules Dassin, Kamera: Max Greene (1950). In: Christian Cargnelli, Michael Omasta (eds.): Schatten. Exil. Europäische Emigranten im Film Noir. PVS, Vienna 1997, ISBN 3-901196-26-9.

External links

- Night and the City at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Night and the City at IMDb

- Night and the City at AllMovie

- Night and the City at the TCM Movie Database

- Night and the City: In the Labyrinth an essay by Paul Arthur at the Criterion Collection

- Night and the City essay by author Geoff Mayer at Film Noir of the Week.

- Night and the City film clip on YouTube (the wrestling scene)