New England Colonies | |

|---|---|

| 1620–1776 | |

.jpg.webp) Map of the New England Colonies in 1755 | |

| Historical era | British colonization of the Americas Puritan migration to New England American Revolution |

| 1607 | |

• Council for New England founded | 1620 the New England Colonies were established 1620 |

| 1620 | |

• Founding of Boston | 1630 |

| 1636 | |

• New England Confederation formed | 1643 |

| 1686-1689 | |

| 1776 | |

• Reorganized as part of the United Colonies | 1776 |

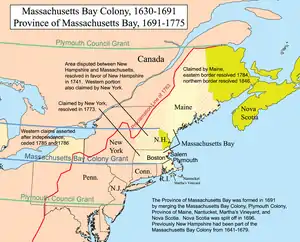

The New England Colonies of British America included Connecticut Colony, the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Massachusetts Bay Colony, Plymouth Colony, and the Province of New Hampshire, as well as a few smaller short-lived colonies. The New England colonies were part of the Thirteen Colonies and eventually became five of the six states in New England, with Plymouth Colony absorbed into Massachusetts and Maine separating from it.[1]

In 1616, Captain John Smith authored A Description of New England, which first applied the term "New England"[2] to the coastal lands from Long Island Sound in the south to Newfoundland in the north.[3]

Arriving in America

England, France, and the Netherlands made several attempts to colonize New England early in the 17th century, and those nations were often in contention over lands in the New World. French nobleman Pierre Dugua Sieur de Monts established a settlement on Saint Croix Island, Maine in June 1604 under the authority of the King of France. Nearly half the settlers perished due to the harsh winter and scurvy, and the survivors moved north out of New England to Port-Royal of Nova Scotia (see symbol "R" on map to the right) in the spring of 1605.[4]

King James I of England recognized the need for a permanent settlement in New England, and he granted competing royal charters to the Plymouth Company and the London Company. The Plymouth Company ships arrived at the mouth of the Kennebec River (then called the Sagadahoc River) in August 1607 where they established a settlement named Sagadahoc Colony, better known as Popham Colony (see symbol "Po" on map to right) to honor financial backer Sir John Popham. The colonists faced a harsh winter, the loss of supplies following a storehouse fire, and mixed relations with the local Indian tribes.

Colony leader Captain George Popham died, and Raleigh Gilbert decided to return to England to take up an inheritance left by an older brother— at which point, all of the colonists decided to return to England. It was around August 1608 when they left on the ship Mary and John and on a new ship built by the colony named Virginia of Sagadahoc. The 30-ton Virginia was the first sea-going ship ever built in North America.[5]

Conflict over land rights continued through the early 17th century, with the French constructing Fort Pentagouet near Castine, Maine in 1613. The fort protected a trading post and a fishing station and was the first longer-term settlement in New England. It changed hands multiple times throughout the 17th century among the English, French, and Dutch colonists.[6]

In 1614, Dutch explorer Adriaen Block traveled along the coast of Long Island Sound and then up the Connecticut River as far as Hartford, Connecticut. By 1623, the Dutch West India Company regularly traded for furs there, and they eventually fortified it for protection from the Pequot Indians and named the site "House of Hope" (also identified as "Fort Hoop," "Good Hope," and "Hope").[7]

Establishing the New England Colonies

A group of Puritans commonly called the Pilgrims arrived on the Mayflower from England and the Netherlands to establish Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts, the second successful English colony in America following Jamestown, Virginia. About half of the 102 passengers on the Mayflower died that first winter, mostly because of diseases contracted on the voyage followed by a harsh winter.[8] In 1621, an Indian named Squanto taught the colonists how to grow corn and where to catch eels and fish. His assistance was invaluable and helped them to survive the early years of colonization. The Pilgrims lived on the same site where Squanto's Patuxet tribe had established a village before they were wiped out from diseases.[9]

The Plymouth settlement faced great hardships and earned few profits, but it enjoyed a positive reputation in England and may have sown the seeds for further immigration. Edward Winslow and William Bradford published an account of their experiences called Mourt's Relation (1622).[10] This book was only a small glimpse of the hardships and dangers encountered by the Pilgrims, but it encouraged other Puritans to immigrate during the Great Migration between 1620 and 1640.

The Puritans in England first sent smaller groups in the mid-1620s to establish colonies, buildings, and food supplies, learning from the Pilgrims' harsh experiences of winter in the Plymouth Colony. In 1623, the Plymouth Council for New England (successor to the Plymouth Company) established a small fishing village at Cape Ann under the supervision of the Dorchester Company. The first group of Puritans moved to a new town at nearby Naumkeag after the Dorchester Company dropped support, and fresh financial support was found by Rev. John White. Other settlements were started in nearby areas; however, the overall Puritan population remained small through the 1620s.[11]

A larger group of Puritans arrived in 1630, leaving England because they desired to worship in a manner that differed from the Church of England. Their views were in accord with those of the Pilgrims who arrived on the Mayflower, except that the Mayflower Pilgrims felt that they needed to separate themselves from the Church of England, whereas the later Puritans were content to remain under the umbrella of the Church. The separate colonies were governed independently of one another until 1691, when Plymouth Colony was absorbed into the Massachusetts Bay Colony to form the Province of Massachusetts Bay.

Spreading out

The Puritans also established the American public school system for the express purpose of ensuring that future generations would be able to read the Bible for themselves, which was a central tenet of Puritan worship.[12] However, dissenters of the Puritan laws were often banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. John Wheelwright left with his followers to establish a colony in New Hampshire and then went on to Maine.

It was the dead of winter in January 1636 when Roger Williams was banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony because of theological differences. One source of contention was his view that government and religion should be separate; he also believed that the colonies should purchase land at fair prices from the Wampanoag and Narragansett tribes. Massachusetts officials intended to forcibly deport him back to England, but he escaped and walked through deep snow from Salem, Massachusetts to Raynham, Massachusetts, a distance of 55 miles. The Indian tribes helped him to survive and sold him land for a new colony which he named Providence Plantations in recognition of the intervention of Divine Providence in establishing the new colony. It was unique in its day in expressly providing for religious freedom and separation of church from state. Other dissenters established two settlements on Rhode Island (now called Aquidneck Island) and another settlement in Warwick; these four settlements eventually united to form the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.[13]

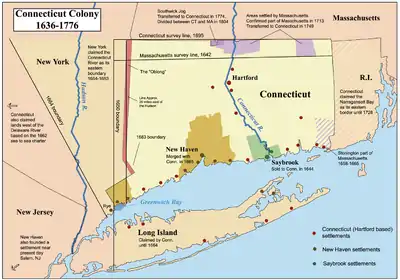

Thomas Hooker left Massachusetts in 1636 with 100 followers and founded a settlement just north of the Dutch Fort Hoop which grew into Connecticut Colony. The community was first named Newtown then renamed Hartford to honor the English town of Hertford. One of the reasons why Hooker left Massachusetts Bay was that only members of the church could vote and participate in the government, which he believed should include any adult male owning property. He obtained a royal charter and established Fundamental Orders, considered to be one of the first constitutions in America. Other colonies later merged into the royal charter for the Connecticut Colony, including New Haven Colony and Saybrook Colony.

Commerce

The earliest colonies in New England were usually fishing villages or farming communities on the more fertile land along the rivers. The rocky soil in the New England Colonies was not as fertile as the Middle or Southern Colonies, but the land provided rich resources, including lumber that was highly valued. Lumber was also a resource that could be exported back to England, where there was a shortage of wood. In addition, the hunting of wildlife provided furs to be traded and food for the table.

The New England Colonies were located along the Atlantic coast where there was an abundance of marketable sea life. Excellent harbors and some inland waterways offered protection for ships and were also valuable for freshwater fishing. By the end of the 17th century, New England colonists had created an Atlantic trade network that connected them to the English homeland as well as to the Slave Coast of West Africa, plantations in the West Indies, and the Iberian Peninsula. Colonists relied upon British and European imports for glass, linens, hardware, machinery, and other items for the household.

The Southern Colonies could produce tobacco, rice, and indigo in exchange for imports, whereas New England's colonies could not offer much to England beyond fish, furs, and lumber. Inflation was a major issue in the economy. During the 18th century, shipbuilding drew upon the abundant lumber and revived the economy, often under the direction of the British Crown.[14]

In 1652, the Massachusetts General Court authorized Boston silversmith John Hull to produce local coinage in shilling, sixpence, and threepence denominations to address a coin shortage in the colony.[15] The colony's economy had been entirely dependent on barter and foreign currency, including English, Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese, and counterfeit coins.[16] In 1661, after the restoration of the monarchy, the English government considered the Boston mint to be treasonous.[17] However, the colony ignored the English demands to cease operations until at least 1682, when Hull's contract expired as mint master, and the colony did not move to renew his contract or appoint a new mint master.[18] The coinage was a contributing factor to the revocation of the Massachusetts Bay Colony charter in 1684.[19]

Indian slavery in the New England Colonies

American Indians who were captured during various conflicts in New England, such as the Pequot War (1636–1638) and King Philip's War (1675–1678), were sometimes sold into slavery.[20] Utilizing captured prisoners of war as a source of forced labor was common in Europe; during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, prisoners of war were frequently indentured and transported to plantations in Barbados and Jamaica.[21]

Plymouth Colony ranger Benjamin Church spoke out against the practice of enslaving Indians in the summer of 1675, describing the practice as "an action so hateful... that [I] opposed it to the loss of the goodwill and respect of some that before were good friends." However, Church was not opposed to black slavery, owning black slaves like many of his fellow colonists.[22] During King Philip's War, some captured Indians were enslaved and transported aboard New England merchant ships to the West Indies, where they were sold to European planters. Various colonial councils decreed that "no male captive above the age of fourteen years should reside in the colony."[23] Margret Ellen Newell estimates that hundreds of Indians were enslaved during the colonial conflicts,[24] while Nathaniel Philbrick estimates that at least 1,000 New England Indians were sold into slavery during King Philip's War, with more than half coming from Plymouth.[25]

Education

In the New England Colonies, the first settlements of Pilgrims and the other Puritans who came later taught their children how to read and write in order that they might read and study the Bible for themselves. Depending upon social and financial status, education was taught by the parents home-schooling their children, public grammar schools, and private governesses, which included subjects from reading and writing to Latin and Greek and more.

Composition

| Coat of Arms/Seal | Name | Capital | Year(s) | Colony type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plymouth | Plymouth | 1620–1686 1689–1691 | Self-governing | Merged into the Dominion of New England in 1686, reformed in 1689, and then merged into Massachusetts in 1691 |

| Massachusetts Bay | Charlestown Salem Boston | 1628–1686 1689–1691 | Self-governing | Merged into the Dominion of New England in 1686, reformed in 1689, and then dissolved in 1691 |

| Saybrook | Saybrook | 1635–1644 | Self-governing | Absorbed by the Connecticut Colony in 1644 |

| None | New Haven | New Haven | 1638–1664 | Self-governing | Absorbed by the Connecticut Colony in 1664 |

| Connecticut River | Hartford | 1636–1776 | Self-governing | Declared independence and reconstituted as the State of Connecticut in 1776 |

| New Hampshire | Portsmouth Exeter | 1629–1641 1679–1686 1689–1776 | Self-governing | At various times absorbed by and/or governed by the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the Province of Massachusetts Bay, declared independence in 1776 |

| Rhode Island and Providence Plantations | Providence Newport | 1636–1686 1689-1776 | Self-governing | Declared independence from Great Britain in 1776 and reorganized as the State of Rhode Island |

| Dominion of New England | Boston | 1686-1689 | Direct rule government | Dissolved as a result of the Glorious Revolution in 1689 |

.svg.png.webp) Royal Seal  Congress Seal | Province of Massachusetts Bay | Boston (de jure) Salem Concord Cambridge Watertown (1774-1776 de facto) | 1691–1780* | Self-governing (1691–1774) Direct rule colonial government (1774–1775) Provisional government (1775–1780) | *From 1776-1780 the Province of Massachusetts Bay existed as a state of the United States. Reconstituted as the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 1780. |

| - | Province of Maine | - | 1622–1652 1680-1686 1689-1692 | Proprietary colony | Merged into the Massachusetts Bay Colony, then into the Dominion of New England in 1686, and absorbed by the Province of Massachusetts Bay in 1692 |

| - | Popham | Fort St. George | 1607-1608 | Proprietary colony | Abandoned |

| - | Sagadahock | - | 1608/9-1691 | Proprietary colony | Incorporated in Province of Massachusetts Bay in 1691 |

| - | Wessagusset | Weymouth | 1622-1623 | Proprietary Colony | Joined Plymouth Colony |

| - | Lygonia | Portland Saco Scarborough | 1630-1658 | Proprietary Colony | Territory contested with the Province of Maine, joined Massachusetts Bay in 1658 |

Provincial arms | Nova Scotia | - | - | - | Part of the Province of Massachusetts Bay 1691-1696 |

.svg.png.webp) Royal arms | Province of New York | - | - | - | Part of the Dominion of New England 1686-1689 |

.svg.png.webp) Royal arms | East Jersey | - | - | - | Part of the Dominion of New England 1686-1689 |

.svg.png.webp) Royal arms | West Jersey | - | - | - | Part of the Dominion of New England 1686-1689 |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Gipson

- ↑ Bisceglia

- ↑ Smith

- ↑ St. Croix Celebration. "St. Croix Island History". Archived from the original on 2001-08-03. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- ↑ "Maine's First Ship: Historic Overview". Maine's First Ship. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ↑ "New France Forts". New France New Horizons. Retrieved 2009-01-10.

- ↑ New York Historical Society, p. 260

- ↑ Deetz, Patricia Scot; James F. Deetz. "Passengers on the Mayflower: Ages & Occupations, Origins & Connections". The Plymouth Colony Archive Project. Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- ↑ NativeAmericans.com. "Squanto (The History of Tisquantum)". Archived from the original on June 5, 2007. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ↑ Bradford, William (1865). Mourt's Relation, or Journal of the Plantation at Plymouth. Boston: J. K. Wiggin. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ↑ Young, Alexander (1846). Chronicles of the First Planters of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, 1623-1636. Boston: C. C. Little and J. Brown. p. 26. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ↑ The Library of Congress Web Site (4 June 1998). "America as a Religious Refuge: The Seventeenth Century". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- ↑ Roger Williams, Family Association. "Biography of Roger Williams". Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- ↑ . N.p.. Web. 20 Aug 2013. <https://www.boundless.com/u-s-history/britain-and-the-settling-of-the-colonies-1600-1750/settling-new-england/commerce-in-the-new-england-colonies/>.

- ↑ Barth 2014, p. 499

- ↑ Clarke, Hermann F. (1937). "John Hull: Mintmaster". The New England Quarterly. 10 (4): 669, 673. doi:10.2307/359931. JSTOR 359931.

- ↑ Barth 2014, p. 500

- ↑ Barth 2014, p. 514

- ↑ Barth 2014, p. 520

- ↑ Newell, Margret Ellen (2015). Brethren by Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 1-158.

- ↑ Nathaniel Philbrick. Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community and War (Viking 2006) p. 253

- ↑ Nathaniel Philbrick. Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community and War (Viking 2006) pp 253, 345

- ↑ Nathaniel Philbrick. Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community and War (Viking 2006) p. 345

- ↑ Newell, Margret Ellen (2015). Brethren by Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 7.

- ↑ Nathaniel Philbrick. Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community and War (Viking 2006) p. 332

Sources

- Barth, Jonathan Edward (2014). "'A Peculiar Stampe of Our Owne': The Massachusetts Mint and the Battle over Sovereignty, 1652-1691". The New England Quarterly. 87 (3): 490–525. doi:10.1162/TNEQ_a_00396. hdl:2286/R.I.26592. JSTOR 43285101. S2CID 57571000.

- Bisceglia, Michael (12 February 2008). "John Smith: The man who named New England". Sea Coast Online. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- Gipson, Lawrence. The British Empire Before the American Revolution (15 volumes) (1936-1970). Knopf.

- Collections of the New York Historical Society. New York: H. Ludwig. 1841.

- Smith, John, Captain & Admiral (1616). Royster, Paul (ed.). "A Description of New England (1616): An Online Electronic Text Edition". Electronic Texts in American Studies (Paper 4).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)