The National Trails System is a series of trails in the United States designated "to promote the preservation of, public access to, travel within, and enjoyment and appreciation of the open-air, outdoor areas and historic resources of the Nation".[2] There are four types of trails: the national scenic trails, national historic trails, national recreation trails, and connecting or side trails. The national trails provide opportunities for hiking and historic education, as well as horseback riding, biking, camping, scenic driving, water sports, and other activities. The National Trails System consists of 11 national scenic trails, 21 national historic trails, over 1,300 national recreation trails, and seven connecting and side trails, as well as one national geologic trail, with a total length of more than 91,000 mi (150,000 km). The scenic and historic trails are in every state, and Virginia and Wyoming have the most running through them, with six.

In response to a call by President Lyndon B. Johnson to have a cooperative program to build public trails for "the forgotten outdoorsmen of today" in both urban and backcountry areas, the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation released a report in 1966 entitled Trails for America.[3] The study made recommendations for a network of national scenic trails, park and forest trails, and metropolitan area trails to provide recreational opportunities, with evaluations of several possible trails, both scenic and historic.[3][4] The program for long-distance natural trails was created on October 2, 1968, by the National Trails System Act, which also designated two national scenic trails, the Appalachian Trail and the Pacific Crest Trail, and requested that an additional fourteen trail routes be studied for possible inclusion.[2] Sponsored by Senators Henry M. Jackson and Gaylord Nelson and Representative Roy A. Taylor,[5] part of the bill's impetus was threats of development along the Appalachian Trail, which was at risk of losing its wilderness character,[4] and the Land and Water Conservation Fund was used to acquire lands.[5] In 1978, as a result of the study of trails that were most significant for their historic associations, national historic trails were created as a new category with four trails designated that year. Since 1968, over forty trail routes have been studied for inclusion in the system.[6]

The scenic and historic trails are congressionally established long-distance trails, administered by the National Park Service (NPS), United States Forest Service (USFS), and/or Bureau of Land Management (BLM). These agencies may acquire lands to protect key rights of way, sites, resources and viewsheds, though the trails do not have fixed boundaries.[4][5] They work in cooperation with each other, states, local governments, land trusts, and private landowners to coordinate and protect lands and structures along these trails, enabling them to be accessible to the public.[7] These partnerships between the agency administrators and local site managers are vital for resource protection and the visitor experience.[5] The Federal Interagency Council on the National Trails System promotes collaboration and standardization in trail development and protection.[7][8] National recreation trails and connecting and side trails do not require congressional action, but are recognized by actions of the secretary of the interior or the secretary of agriculture. The national trails are supported by volunteers at private non-profit organizations that work with the federal agencies under the Partnership for the National Trails System and other trail type-specific advocacy groups.[7][4]

For fiscal year 2021, the 24 trails administered by the NPS received a budget of $15.4 million.[9]

National Scenic Trails

The eleven national scenic trails were established to provide outdoor recreation opportunities and to conserve portions of the natural landscape with significant scenic, natural, cultural, or historic importance.[10] These trails are continuous non-motorized long-distance trails that can be backpacked from end-to-end or hiked for short segments, except for Natchez Trace NST, which consists of five shorter, disconnected trail segments.[11] The Trails for America report said, "Each National Scenic Trail should stand out in its own right as a recreation resource of superlative quality and of physical challenge."[12] Most notably, the national scenic trail system provides access to the crest of the Appalachian Mountains in the east via the Appalachian Trail, of the Rocky Mountains in the west on the Continental Divide Trail, and of the Cascade and Sierra Nevada ranges on the Pacific Crest Trail, which make up the Triple Crown of Hiking. Other places of note include the southern wetlands and Gulf Coast on the Florida Trail, the North Woods on the North Country Trail, the variety of southwestern mountains and ecosystems on the Arizona Trail, and the remote high-mountain landscape near the Canadian border on the Pacific Northwest Trail.

They have a total length of approximately 17,800 mi (28,650 km). Due to the extent of construction of route realignments, segment alternatives, and measurement methods, some sources vary in their distances reported and values may be rounded.[5]

Six trails are official units of the NPS, managed like its other areas, as long, linear parks.[4][13] Five trails are overseen by the U.S. Forest Service.

In 2022 Arlette Laan, whose trail name was "Apple Pie", became the first woman known to have completely hiked all eleven national scenic trails.[14]

| Name | Image | States on route | Agency | Year est.[15] | Length[15] | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appalachian | _(10355280153).jpg.webp) |

Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine | NPS | 1968 | 2,189 mi (3,520 km) | Spanning the Appalachian Mountains from Springer Mountain in Georgia and Mount Katahdin in Maine, this trail dating to the 1920s sees around a thousand thru-hikers each year, along with millions of short-term visitors. Major parks on the route include Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Shenandoah National Park, Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area (pictured), and White Mountain National Forest.[16] |

| Arizona |  |

Arizona | USFS | 2009 | 800 mi (1,290 km) | Extending the entire length of the state from Coronado National Memorial (pictured) near the Mexican border to Utah, this trail covers the variety of Arizona's deserts, mountains, and canyons. Four scenic regions have distinct landscapes and biotic communities: the sky islands with Saguaro National Park and Coronado National Forest, the Sonoran uplands of Tonto National Forest, the volcano field crossing the San Francisco Peaks, and the plateaus divided by the Grand Canyon.[17] |

| Continental Divide |  |

Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico | USFS | 1978 | 3,200 mi (5,150 km) | With a route from Mexico to Canada, the Continental Divide separates the nation's rivers between those that flow into the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Mostly following the crest of the Rocky Mountains, its major sites include El Malpais National Monument; Gila Wilderness; Wind River Range; and Rocky Mountain, Yellowstone, and Glacier National Parks (pictured).[18] |

| Florida |  |

Florida | USFS | 1983 | 1,500 mi (2,410 km) | The Florida Trail runs from the swamplands of Big Cypress National Preserve to the beaches of Gulf Islands National Seashore, going around Lake Okeechobee and through Ocala, Osceola, and Apalachicola National Forests and many state forests and parks.[19] |

| Ice Age |  |

Wisconsin | NPS | 1980 | 1,000 mi (1,610 km) | This trail traces Wisconsin's terminal moraine of the glacier covering much of North America in the last ice age. When it receded about 10,000 years ago, it left behind kettles, potholes, eskers, kames, drumlins, and glacial erratics, six sites of which are part of the Ice Age National Scientific Reserve (Kettle Moraine State Forest pictured).[20] |

| Natchez Trace |  |

Tennessee, Mississippi | NPS | 1983 | 64 mi (100 km) | The Natchez Trace was used for centuries by Native Americans who followed animal migration paths as trade routes. It became a major road for settlers to the South in the 1800s and 1810s before falling out of use, and it is now preserved as the Natchez Trace Parkway. The full intended length has not been developed and the trail consists of five disconnected sections – from three to twenty-six miles long – through forests and prairies next to the 444 km (276 mi) parkway.[11] |

| New England |  |

Massachusetts, Connecticut | NPS | 2009 | 215 mi (350 km) | This footpath incorporates the Metacomet-Monadnock Trail, Metacomet Trail (Ragged Mountain pictured), and Mattabesett Trail from Long Island Sound to the New Hampshire border. It crosses the mountains of the Metacomet Ridge, connecting small towns, farms, and forests with lakes and traprock ridges.[21] |

| North Country |  |

North Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Vermont | NPS | 1980 | 4,800 mi (7,720 km) | This trail reaches from Lake Sakakawea State Park in North Dakota to a junction with the Appalachian Trail in Green Mountain National Forest in Vermont. Along its route, the trail passes through eight states and more than 150 parcels of land protected at the federal, state, or local levels.[22][23] |

| Pacific Crest |  |

California, Oregon, Washington | USFS | 1968 | 2,650 mi (4,260 km) | The PCT follows the passes and crests of the San Bernardino Mountains, Sierra Nevada, Cascades, and several other ranges from the Mexican to Canadian borders. It passes through 7 national parks, including Yosemite, Crater Lake, and North Cascades, and 25 national forests, for a route crossing deserts, glaciated mountains, pristine forests and lakes, and volcanic peaks. More than half is in federal wilderness areas (Alpine Lakes Wilderness pictured).[24][25] |

| Pacific Northwest |  |

Montana, Idaho, Washington | USFS | 2009 | 1,200 mi (1,930 km) | Connecting the Continental Divide at Glacier National Park to the Pacific Ocean at Olympic National Park, this trail showcases the Rocky Mountains, Okanogan Highlands, North Cascades, Puget Sound (including a ferry ride), and the Olympic Peninsula (Olympic National Park pictured).[26] |

| Potomac Heritage |  |

Pennsylvania, Maryland, District of Columbia, Virginia | NPS | 1983 | 710 mi (1,140 km) | The Potomac River is a corridor connecting the country's capital with historic trade and transportation routes to the ocean and inland. This network of trails incorporates the Laurel Highlands Hiking Trail and Great Allegheny Passage in the Allegheny Mountains, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal towpath (Great Falls pictured), the Mount Vernon Trail to George Washington's estate, cycling routes to the mouth of the river, and several other trails.[27] |

National Historic Trails

The 21 national historic trails are designated to protect the courses of significant overland or water routes that reflect the history of the nation.[15] They represent the earliest European travels in the country in Chesapeake Bay and on Spanish royal roads; the nation's struggle for independence on the Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail and Washington–Rochambeau Revolutionary Route; westward migrations on the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails, which traverse some of the same route; and the development of continental commerce on the Santa Fe Trail, Old Spanish Trail, and Pony Express. They also memorialize the forced displacement and hardships of the Native Americans on the Trail of Tears and Nez Perce National Historic Trail.

Their routes follow the nationally significant, documented historical journeys of notable individuals or groups but are not necessarily meant to be continuously traversed today; they are largely networks of partner sites along marked auto routes rather than the exact non-motorized trails as originally used.[5] Interpretative sites are often at other areas of the National Park System along the trails, as well as locally operated museums and sites.[28] The National Historic Trails Interpretive Center in Wyoming is on the Oregon, California, Mormon Pioneer, and Pony Express National Historic Trails and has exhibits on Western emigration.[29] Nine are administered by the NPS National Trails Office in Santa Fe and Salt Lake City.[30]

National historic trails were authorized under the National Parks and Recreation Act of 1978 (Pub. L. 95–625), amending the National Trails System Act of 1968. They have a total length of approximately 40,000 mi (64,370 km); many trails include several branches making them much longer than a single end-to-end distance.

| Name | Image | States on route | Agency | Year est.[15] | Length[15] | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ala Kahakai |  |

Hawaii | NPS | 2000 | 175 mi (280 km) | Trail segments on the west and south shores of Hawaiʻi island protect the ancient ala loa (long trail) used by Native Hawaiians for generations. This natural and cultural landscape crosses lava flows of Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park and sandy beaches with anchialine pools. Archaeological sites include Kaloko-Honokōhau (wetlands and fishponds) and Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Parks (place of refuge) and Puʻukoholā Heiau National Historic Site (Kamehameha I's temple).[31] |

| Butterfield Overland |  |

Missouri, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, California | NPS | 2023 | 3,292 mi (5,300 km) | The Butterfield Overland Mail Company operated a stagecoach route between 1858 and 1861 to transport mail and passengers along a southern route between St. Louis and Memphis and San Francisco. Founded by John Butterfield, the route had nine divisions traversed by higher-speed wagons until the Civil War broke out.[32] |

| California |  |

Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, Nevada, California, Oregon | NPS | 1992 | 5,600 mi (9,010 km) | The 1841 Bartleson–Bidwell Party, 1844 Stephens–Townsend–Murphy Party, and 1846 Donner Party (Donner Pass pictured) were among the few early overland emigrants to northern California, but the discovery of gold at Sutter's Mill in 1848 sparked the massive California Gold Rush. Some 140,000 "Forty-Niners" made the trip over the next five years via the overland emigrant trail starting in Missouri, going along the Platte River, around the Great Salt Lake, and over the Sierra Nevada (the same number came by sea). Several branching cutoffs and routes to the mines and supporting cities developed, the most popular being the Carson Trail to Sutter's Fort, Sacramento. While the population explosion led to California's statehood, it also resulted in the genocide of the state's Native Americans.[33] |

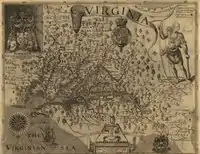

| Captain John Smith Chesapeake |  |

Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, District of Columbia | NPS | 2006 | 3,000 mi (4,830 km) | This is a water trail based on the routes John Smith, a founder of the Jamestown settlement, took to survey Chesapeake Bay in 1607–1609. On Smith's explorations he mapped (pictured) the Bay's tributaries and communities of Native Americans he met. The trail today includes a network of historical and natural partner sites, including maritime museums, wildlife refuges, state and local parks, and interpretive buoys, in addition to water trails for canoeing and kayaking.[34] |

| Chilkoot |  |

Alaska | NPS | 2022 | 16.5 mi (30 km) | Originally used as a trade route between the coast and the interior by Tlingit people, the Chilkoot Trail was a main access route to the Yukon during the Klondike Gold Rush. Between 1896 and 1899 around 22,000 prospectors made their way from Dyea, Alaska to Bennett Lake, British Columbia, carrying one ton of gear across Chilkoot Pass. It is part of the Skagway unit of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, and continues as Chilkoot Trail National Historic Site in B.C. Together, they form parts of Klondike Gold Rush International Historical Park. Thousands of visitors now hike on the route each year, from the coastal rainforest to high alpine mountains.[35] |

| El Camino Real de los Tejas |  |

Texas, Louisiana | NPS | 2004 | 2,600 mi (4,180 km) | The Royal Road of the Tejas is the group of roads through Spanish Texas established by its first governors in the 1680s and 1690s. The Spanish initially attempted trade and proselytization at Mission Tejas in Eastern Texas and Los Adaes, Louisiana, before moving the capital to San Antonio and building a series of missions (Mission Espada pictured) in the early 18th century. Mexican and American ranchers settled along the corridor toward the Rio Grande, including the Old San Antonio Road, through Texas independence and annexation in 1845.[36] |

| El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro |  |

New Mexico, Texas | NPS, BLM | 2000 | 404 mi (650 km) | The Royal Road of the Interior was first routed by Juan de Oñate in 1598 to colonize the northern part of New Spain. It was used for hundreds of years for trade and communication between Mexico City and Santa Fe, mostly following the Rio Grande north of El Paso, including the Jornada del Muerto and Bajada Mesa sections. The Spanish developed the region with missions like the Presidio Chapel of San Elizario and Ysleta Mission (pictured), governed from the Palace of the Governors, later used by the Mexican and US administrations. Other historic sites include El Rancho de las Golondrinas, Mesilla Plaza, the Gutiérrez Hubbell House, and Fort Craig and Fort Selden used by the U.S. Army in the 1860s.[37][38] |

| Iditarod | .jpg.webp) |

Alaska | BLM | 1978 | 2,350 mi (3,780 km) | This route from Seward to Nome was used by some prospectors to reach the Nome Gold Rush in the early 1900s, connecting trails long used by Alaska Natives. In the 1925 serum run, a relay of mushers and their sled dogs brought an antitoxin to Nome to stop a diphtheria outbreak, but the trail fell into disuse as planes replaced sleds for shipping. In commemoration of this history the 1,000 mi (1,600 km) Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race has been held annually since 1973. The only winter trail in the system, the designated trail includes the race route and 1,400 mi (2,300 km) of trails connecting nearby communities for snowmobiling, sledding, and skiing.[39] |

| Juan Bautista de Anza |  |

Arizona, California | NPS | 1990 | 1,200 mi (1,930 km) | Juan Bautista de Anza led a 240-person expedition in 1775–1776 to colonize Las Californias, going from the Tubac Presidio near Tucson to San Francisco Bay, where he sited the Presidio of San Francisco and Mission San Francisco de Asís. Anza visited Missions San Gabriel Arcángel, San Luis Obispo, San Antonio, and San Carlos Borromeo (pictured), and his route became El Camino Real, which now has 21 missions. A full-length auto trail and several recreation trails connect these Hispanic heritage sites and other places they went through including Casa Grande Ruins and Anza-Borrego Desert State Park.[40] |

| Lewis and Clark |  |

Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Kansas, Iowa, Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, Montana, Idaho, Oregon, Washington. | NPS | 1978 | 4,900 mi (7,890 km) | Meriwether Lewis and William Clark led the 1803–1806 Corps of Discovery Expedition to map and study the Louisiana Purchase for President Thomas Jefferson. On their round-trip up the Missouri River to the mouth of the Columbia River, they formed relationships with many Native American tribes and described dozens of species. Associated sites along the trail, extended in 2019 to encompass their preparation along the Ohio River, include their starting point Camp Dubois near Gateway Arch National Park, winter camp Fort Clatsop (replica pictured) at Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, Pompeys Pillar National Monument, and an NPS visitor center in Omaha.[41] |

| Mormon Pioneer |  |

Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Wyoming, Utah | NPS | 1978 | 1,300 mi (2,090 km) | Facing persecution at their settlement in Nauvoo, Illinois, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons), led by Brigham Young, followed the Emigrant Trail to reach refuge in the Salt Lake Valley. Around 2,000 Mormon pioneers completed the original 1846–1847 trek, including stops at Mount Pisgah, Iowa; Winter Quarters, Nebraska; and Fort Laramie, Wyoming. In the next two decades, 70,000 more followed on the arduous route, some pulling handcarts. Among the 145 participating sites to visit today are Independence Rock (pictured), Devil's Gate, and This Is the Place Heritage Park.[42] |

| Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) | .jpg.webp) |

Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, Montana | USFS | 1986 | 1,170 mi (1,880 km) | In 1877 the Nez Perce (Nimíipuu) people were forced to relocate to a reservation, but a group of 750 people led by Chief Joseph fled to reach sanctuary. A U.S. Army unit of 2,000 soldiers pursued the band for four months as the Nez Perce warriors held them off at several battles until they were cornered and captured at the Battle of Bear Paw. Their route can be traced on an auto tour, visiting Big Hole National Battlefield (pictured), Camas Meadows Battle Sites, Yellowstone National Park, and other sites of Nez Perce National Historical Park.[43][44] |

| Old Spanish |  |

New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Arizona, Nevada, California | NPS, BLM | 2002 | 2,700 mi (4,350 km) | Mexican merchant Antonio Armijo led the first trade expedition from Abiquiú, New Mexico, to Los Angeles and back in 1829, crossing areas mapped on the 1776 Domínguez–Escalante expedition and by Jedediah Smith in 1826. Wolfskill and Yount traced an alternate northern route the next year, providing New Mexican trade caravans and emigrants access to California on mules until a wagon route was built by the 1850s. Little evidence of the trails remains, but landmarks include Mojave National Preserve, Great Sand Dunes National Park, and Lake Mead National Recreation Area.[45][46] |

| Oregon |  |

Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, Oregon, Washington | NPS | 1978 | 2,170 mi (3,490 km) | Marcus Whitman made the first wagon trek to Oregon Country in 1836 to found the Whitman Mission, followed by the Oregon Dragoons and Bartleson–Bidwell Party. Whitman led a wagon train of around 1,000 emigrants in 1843, with tens of thousands of families making the risky journey over the next few decades to reach a new life in the West. The trail's typical endpoints were Independence, Missouri to Oregon City, Oregon, via Fort Kearny, Scotts Bluff (pictured), South Pass, Shoshone Falls, the Blue Mountains, and Barlow Road. Emigrants came in mule- or oxen-pulled covered wagons filled with months of supplies, but they also faced disease and attacks by Native Americans upon whose land they intruded.[47] |

| Overmountain Victory |  |

Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina | NPS | 1980 | 330 mi (530 km) | In September 1780 during the Revolutionary War, the Overmountain Men militia mustered in Abingdon, Virginia (pictured) and Sycamore Shoals, Tennessee, for a two-week march across the Appalachian Mountains via Roan Mountain. Pursuing British Major Patrick Ferguson, they confronted his Loyalist force at the October 7 Battle of Kings Mountain in South Carolina, where the Patriots won a quick, decisive victory that would be a turning point in the war. The linked highways and walking trails visit several preserved encampment sites.[48] |

| Pony Express |  |

Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, California | NPS | 1992 | 2,000 mi (3,220 km) | Lasting just 18 months in 1860–1861, the Pony Express delivered mail via horseback between St. Joseph, Missouri, and Sacramento, California. Riders relayed communications 1,800 mi (2,900 km) across the country in just ten days until the transcontinental telegraph put the service operated by Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company out of business. While little of the trail itself remains, 50 stations or their ruins of the original 185 can still be visited, including Hollenberg Pony Express Station (pictured), Fort Caspar, Stagecoach Inn, the Pike's Peak Stables and Patee House at the eastern terminus, and B.F. Hastings Building at the western terminus.[49] |

| Santa Fe |  |

Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Colorado, New Mexico | NPS | 1987 | 1,203 mi (1,940 km) | William Becknell made the first trade trip from Missouri to Santa Fe in 1821, when newly independent Mexico welcomed commerce. It was a major exchange route between the two countries for the next 25 years when the Army of the West used it in the Mexican–American War. After the war ended in 1848, emigration and freight to the new southwest flourished. The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway reached Santa Fe via Raton Pass in 1880, replacing the trade caravans. Significant sites include Fort Larned, Bent's Old Fort, and Fort Union (pictured), where wagon ruts can still be seen.[50] |

| Selma to Montgomery | .jpg.webp) |

Alabama | NPS | 1996 | 54 mi (90 km) | The 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches were nonviolent demonstrations of the civil rights movement pushing for the Voting Rights Act. Led by John Lewis and Hosea Williams, 600 marchers were brutally attacked by state police at Selma's Edmund Pettus Bridge (pictured), rousing national support for the bill. Another march a month later saw the protestors complete the four-day walk from Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church to the Alabama State Capitol, where Martin Luther King Jr. spoke before a crowd of 25,000. The trail has historical markers and three interpretive centers.[51] |

| Star-Spangled Banner |  |

Maryland, Virginia, District of Columbia | NPS | 2008 | 290 mi (470 km) | This water and land trail highlights the history of the War of 1812 in the Chesapeake Bay Region. Major sites of this three-year war between the United States and United Kingdom include raided towns Havre de Grace and Saint Michaels; grounds of the Battle of Bladensburg and Battle of North Point; and Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine (pictured), where the flying of the American flag in the Battle of Baltimore inspired "The Star-Spangled Banner".[52] |

| Trail of Tears |  |

Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma | NPS | 1987 | 5,045 mi (8,120 km) | The 1830 Indian Removal Act forced tens of thousands of Cherokee, Muscogee, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw people to leave their ancestral homelands in the Southeast and relocate to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). Around ten thousand Indians died of disease or the elements on their journeys. This trail commemorates the routes taken by the Cherokee after they were evicted and detained in camps by the Army in 1838, making the four-month trek over the winter. Historic sites include the Cherokee capital New Echota in Georgia (pictured), Chief John Ross's log cabin, Red Clay State Park, Rattlesnake Springs, and several museums.[53] |

| Washington–Rochambeau Revolutionary Route |

|

Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, District of Columbia, Massachusetts | NPS | 2009 | 1,000 mi (1,610 km) | Six years into the Revolutionary War, the French Expédition Particulière commanded by the comte de Rochambeau departed Newport, Rhode Island, to meet George Washington's Continental Army at Dobbs Ferry, New York, in June 1781. They marched to Williamsburg, Virginia, over the next few months, stopping at the Old Barracks in Trenton and Mount Vernon. In the three-week siege of Yorktown (now part of Colonial National Historical Park, reenactment pictured) they defeated General Cornwallis's army, soon clinching independence for the 13 colonies. Several campsites and homes on their route are preserved, including the Joseph Webb House where Washington and Rochambeau made plans for the campaign.[54] |

Connecting or side trails

The act also established a category of trails known as connecting or side trails. Though there are no guidelines for how these are managed, these have been designated by the secretary of the interior to extend trails beyond the original congressionally established route. Seven side trails have been designated:[5]

- Timms Hill Trail – 14 mi (23 km), connects the Ice Age Trail to Wisconsin's highest point, Timms Hill (1990)[4]

- Anvik Connector – 86 mi (138 km), joins the Iditarod Trail to the village of Anvik, Alaska (1990)[4]

- Susquehanna River Component Connecting Trail – 552 mi (888 km), extends the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail up the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania and New York (2012)[55]

- Chester River Component Connecting Trail – 46 mi (74 km), extends the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail up the Chester River in Maryland (2012)[55]

- Upper Nanticoke River Component Connecting Trail – 23 mi (37 km), extends the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail up the Nanticoke River in Delaware (2012)[55]

- Upper James River Component Connecting Trail – 220 mi (350 km), extends the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail up the James River in Virginia (2012)[55]

- Marion to Selma Connecting Trail – 28 mi (45 km), connects the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail to Marion, Alabama, where Jimmie Lee Jackson was murdered in 1965 (2015)[56]

National Recreation Trails

National recreation trail (NRT) is a designation given to existing trails that contribute to the recreational and conservation goals of a national network of trails. Over 1,300 trails over all fifty states have been designated as NRTs on federal, state, municipal, tribal and private lands that are available for public use and are less than a mile to more than 500 miles (800 km) in length.[57] They have a combined length of more than 29,000 miles (47,000 km).[58]

Most NRTs are hiking trails, but a significant number are multi-use trails or bike paths, including rail trails and greenways. Some are intended for use with watercraft, horses, cross-country skis, or off-road recreational vehicles.[59] There are a number of water trails that make up the National Water Trails System subprogram.[60] Eligible trails must be complete, well designed and maintained, and open to the public.[59]

The NPS and the USFS jointly administer the National Recreation Trails Program with help from other federal and nonprofit partners, notably American Trails, the lead nonprofit for developing and promoting NRTs.[57] The secretary of interior or the secretary of agriculture (if on USFS land) designates national recreation trails that are of local and regional significance. Managers of eligible trails can apply for designation with the support of all landowners and their state's trail coordinator (if on non-federal land).[59] Designated trails become part of the National Trails System and receive promotional benefits, use of the NRT logo, technical and networking assistance, and preference for funding through the Department of Transportation's Recreational Trails Program.[61]

American Trails sponsors an annual NRT photo contest[62] and a biennial symposium[63] and maintains the NRT database.[58]

National Geologic Trail

The first national geologic trail was established by the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009, though it did not amend the National Trails System Act to create an official category.[64]

| Name | Image | States on route | Agency | Year est. | Length | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ice Age Floods | .jpg.webp) |

Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana | NPS | 2009 | 3,400 mi (5,470 km) | From around 18,000 to 15,000 years ago, the glacial Lake Missoula breached its ice dams 40 to 100 times, each time releasing the cataclysmic Missoula floods that carved coulees, lakes, cliffs, waterfalls, and giant current ripples along their path. They created the Channeled Scablands that form much of eastern Washington's landscape of irregular buttes and basins and the Columbia River Gorge past the Wallula Gap. An unmarked tour route connects a network of state parks and other featured sites formed in these erosive floods such as Steamboat Rock State Park, Dry Falls (pictured), Palouse Falls, and the Grand Coulee.[65][66] |

See also

References

- ↑ "The National Historic Trail Logos - National Trails Office - Regions 6, 7, 8 (U.S. National Park Service)". National Park Service. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- 1 2 16 U.S.C. § 1241

- 1 2 "Trails for America" (PDF). Department of the Interior – Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. December 1966.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "The National Trails System". About.com. June 6, 1999. Archived from the original on November 10, 2000. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Reference Manual 45 – National Trails System" (PDF). National Park Service. January 2019.

- ↑ 16 U.S.C. §§ 1241–1251

- 1 2 3 "The National Trails System Memorandum of Understanding" (PDF). National Park Service. 2016.

- ↑ "2017 Federal Agency Highlights for the National Trails System". Partnership for the National Trails System. January 31, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ "BUDGET JUSTIFICATIONS and Performance Information Fiscal Year 2022: National Park Service" (PDF). National Park Service. 2021. p. 61.

- ↑ "History of the National Trails System". American Trails. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- 1 2 "Natchez Trace National Scenic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Continental Divide National Scenic Trail | US Forest Service". U.S. Forest Service. February 12, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ↑ "Three national scenic trails designated as units of the National Park System". National Park Service. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ↑ Lewis, Chelsey (July 13, 2022). "Ice Age Trail thru-hiker becomes first woman to complete all 11 national scenic trails". Journal Sentinel.

- 1 2 3 4 5 The National Parks: Index 2012–2016 (PDF). National Park Service. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 13, 2018.

- ↑ "Appalachian National Scenic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Arizona National Scenic Trail". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Continental Divide National Scenic Trail". U.S. Forest Service. February 12, 2019. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Florida National Scenic Trail". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Ice Age National Scenic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "New England National Scenic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "North Country National Scenic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Explore the Trail". North Country Trail Association. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ↑ "Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Discover the Pacific Crest Trail". Pacific Crest Trail Association. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ↑ "Pacific Northwest National Scenic Trail – About the Trail". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Certified Sites - National Trails Office - Regions 6, 7, 8". National Park Service. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ↑ "National Historic Trails Center". National Historic Trails Center. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ↑ "National Trails Office - Regions 6, 7, 8". National Park Service. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ↑ "Ala Kahakai National Historic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Butterfield Trail gets national historic designation". Arkansas Online. December 23, 2022. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ↑ "California Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Explore the Chilkoot Trail - Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park". National Park Service. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

- ↑ "El Camino Real de los Tejas National Historic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail". Bureau of Land Management. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ↑ "Iditarod National Historic Trail". Bureau of Land Management. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Mormon Pioneer National Historic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Nez Perce National Historic Trail". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Nez Perce National Historical Park". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Old Spanish National Historic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Old Spanish Trail National Historic Trail". Bureau of Land Management. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ↑ "Oregon National Historic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Pony Express National Historic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Santa Fe National Historic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Star-Spangled Banner National Historic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Trail of Tears National Historic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route National Historic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "America's Great Outdoors: Secretary Salazar Expands Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail". Department of the Interior. May 16, 2012. Retrieved May 12, 2021. Map

- ↑ Koplowitz, Howard (July 20, 2015). "Marion added to Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail". AL.com. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- 1 2 "National Recreation Trails - National Trails System". National Park Service. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- 1 2 "National Recreation Trails Database". American Trails. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- 1 2 3 "How To Apply for NRT Designation". American Trails. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ↑ "National Water Trails System - National Trails System". National Park Service. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ↑ "Benefits of NRT Designation". American Trails. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ↑ "Photo Contest". American Trails. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ↑ "The International Trails Symposium". American Trails. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ↑ "[USC02] 16 USC 1244: National scenic and national historic trails". US House of Representatives. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- ↑ "Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail". National Park Service. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail Long-Range Interpretive Plan" (PDF). National Park Service. June 2016.

Further reading

- Karen Berger, Bart Smith (photography), and Bill McKibben (foreword): America's Great Hiking Trails. Rizzoli, 2014, ISBN 978-0789327413

- Karen Berger, Bart Smith (photography), and Ken Burns & Dayton Duncan (foreword) (2014), America's National Historic Trails: Walking the Trails of History. Rizzoli, 2020, ISBN 978-0847868858

External links

- Partnership for National Trails System

- National Trails System – National Park Service

- America's National Trails – U.S. Forest Service

- National Scenic and Historic Trails – Bureau of Land Management

- National Recreation Trails Program – American Trails

- National Recreation Trails database

- The National Trails System: A Brief Overview – Congressional Research Service