Natarajasana (Sanskrit: नटराजासन, romanized: Naṭarājāsana), Lord of the Dance Pose[1] or Dancer Pose[2] is a standing, balancing, back-bending asana in modern yoga as exercise.[1] It is derived from a pose in the classical Indian dance form Bharatnatyam, which is depicted in temple statues in the Nataraja Temple, Chidambaram. Nataraja, the "Dancing King", is in turn an aspect of the Hindu God Shiva, depicted in bronze statues from the Chola dynasty. The asana was most likely introduced into modern yoga by Krishnamacharya in the early 20th century, and taken up by his pupils, such as B. K. S. Iyengar, who made the pose his signature. Natarajasana is among the yoga poses often used in advertising, denoting desirable qualities such as flexibility and grace.

Etymology and mythology

The name comes from the Sanskrit epithet नटराज Naṭarāja, "Dancing King",[lower-alpha 1] one of the names given to the Hindu God Shiva in his form as the cosmic dancer,[4] and आसन āsana meaning "posture" or "seat".[5] Nataraja is the aspect of Shiva "whose ecstatic dance of destruction lays the foundation for the creation and sustenance of the universe."[6] The significance of the image of the dancing Shiva is indicated by his gestures: he is depicted with four arms, standing on Avidya, the demon of ignorance. In his hands he beats out time on a drum, and holds the flame of Vidya, knowledge. Sometimes he holds a conch shell, signifying Om, the universal cosmic sound. He holds up a hand in the gesture of fearlessness, Abhayamudra.[6]

The pose is among some twenty asanas depicted in 13th – 18th century Bharatnatyam dance statues of the Eastern Gopuram, Nataraja Temple, Chidambaram.[7]

In modern yoga

The yoga guru B. K. S. Iyengar in Natarajasana |

"As the signature pose of Iyengar, the most acclaimed master of postural yoga, Natarajasana became the representative yoga pose of the late 20th century... Iyengar saw himself as Nataraja's avatar. And he clearly (sometimes desperately) wanted us to see him as the incarnation of Nataraja. So he came close to conflating the yogin and the dancer." — Elliott Goldberg[8] |

The yoga scholar Elliott Goldberg observes that Natarajasana is not found in any medieval hatha yoga text, nor is it mentioned by any pre-20th century traveller to India, or found in artistic depictions of yoga such as the Sritattvanidhi or the Mahamandir near Jodhpur. Goldberg argues that the pose, like several others, was introduced into modern yoga by Krishnamacharya in the early 20th century, and taken up by his pupils such as B. K. S. Iyengar, who made the pose a signature of modern yoga; Goldberg suggests that Iyengar transmitted the pose also to Sivananda, as Iyengar sent him a complete photo album showing Iyengar in all his asanas.[8] Iyengar writes in the coverage of Natarajasana in his Light on Yoga that the god Shiva created over 100 dances, from gentle to fierce, of which the best-known is the Tāṇḍava, "the cosmic dance of destruction".[9] He describes Natarajasana as a "vigorous and beautiful pose", and is pictured demonstrating the pose on the cover of some editions of his book.[9]

Description

This aesthetic, stretching and balancing asana is said to require concentration and grace;[10] it is used in the Indian classical dance form Bharatanatyam.[7] The actor Mariel Hemingway describes Natarajasana as "a beautiful pose with tremendous power", comparing the balance and tension in the arms and legs with an archery bow, and calling it "a very difficult pose to hold."[11]

The pose is entered from standing in Tadasana, bending one knee and stretching that foot back until it can be grasped with the hand on that side. The foot can then be extended back and up, arching the back and stretching out the other arm forwards.[12][1] For the full pose and a stronger stretch, reverse the rear arm by lifting it over the shoulder, and grasp the foot.[1]

Variations

Reaching up and back with both arms, elbows upwards, to grasp the rear foot gives a more intense pose.[2]

The pose can be modified by grasping a strap around the rear foot,[12] or by holding on to a support such as a wall or chair.[2]

Natarajasana in Bharatanatyam classical Indian dance

Natarajasana in Bharatanatyam classical Indian dance Variation with both hands grasping the raised foot

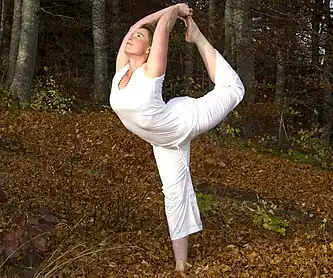

Variation with both hands grasping the raised foot A variation demonstrated by the Russian yoga teacher Nina Mel

A variation demonstrated by the Russian yoga teacher Nina Mel Outdoor class in Liechtenstein

Outdoor class in Liechtenstein

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Lord of the Dance Pose". Yoga Journal. 28 August 2007.

- 1 2 3 Swanson, Ann (2019). Science of yoga : understand the anatomy and physiology to perfect your practice. New York, New York: DK Publishing. pp. 114–117. ISBN 978-1-4654-7935-8. OCLC 1030608283.

- ↑ Gerstein, Nancy (2008). Guiding Yoga's Light: Lessons for Yoga Teachers. Human Kinetics. pp. 118–. ISBN 978-0-7360-7428-5.

- ↑ Coomaraswamy, Ananda (1957). The Dance of Śiva: Fourteen Indian Essays. Sunwise Turn. pp. 58–59. OCLC 2155403.

- ↑ Sinha, S. C. (1996). Dictionary of Philosophy. Anmol Publications. p. 18. ISBN 978-81-7041-293-9.

- 1 2 Kaivalya, Alanna (15 November 2013). "Joy to the World: Lord of the Dance". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- 1 2 Bhavanani, Ananda Balayogi; Bhavanani, Devasena (2001). "BHARATANATYAM AND YOGA". Archived from the original on 23 October 2006.

He also points out that these [Bharatanatyam dance] stances are very similar to Yoga Asanas, and in the Gopuram walls at Chidambaram, at least twenty different classical Yoga Asanas are depicted by the dancers, including Dhanurasana, Chakrasana, Vrikshasana, Natarajasana, Trivikramasana, Ananda Tandavasana, Padmasana, Siddhasana, Kaka Asana, Vrishchikasana and others.

- 1 2 Goldberg, Elliott (2016). The Path of Modern Yoga : the history of an embodied spiritual practice. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions. pp. 223, 395–398, and cover image. ISBN 978-1-62055-567-5. OCLC 926062252.

As the signature pose of Iyengar, the most acclaimed master of postural yoga, Natarajasana became the representative yoga pose of the late 20th century... Iyengar saw himself as Nataraja's avatar. And he clearly (sometimes desperately) wanted us to see him as the incarnation of Nataraja. So he came close to conflating the yogin and the dancer.

- 1 2 Iyengar, B. K. S. (1991) [1966]. Light on Yoga. Thorsons. pp. 419–422. ISBN 978-1855381667.

- ↑ Ramaswami, Srivatsa (2001). Yoga for the three stages of life: developing your practice as an art form, a physical therapy, and a guiding philosophy. Inner Traditions. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-89281-820-4.

- ↑ Hemingway, Mariel (2004) [2002]. Finding My Balance: A Memoir with Yoga. Simon & Schuster. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-0743264327.

- 1 2 StPierre, Amber (9 January 2017). "Troubleshooting King Dancer Pose". DoYouYoga. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

Further reading

- Saraswati, Swami Satyananda (1 August 2003). Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha. Nesma Books India. ISBN 978-81-86336-14-4. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- Saraswati, Swami Satyananda (January 2004). A Systematic Course in the Ancient Tantric Techniques of Yoga and Kriya. Nesma Books India. ISBN 978-81-85787-08-4. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

_from_Jogapradipika_1830_(cropped).jpg.webp)