| Nasal cavity | |

|---|---|

Head and neck | |

Conducting passages | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Nose |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cavum nasi; cavitas nasi |

| MeSH | D009296 |

| TA98 | A06.1.02.001 |

| TA2 | 3165 |

| FMA | 54378 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

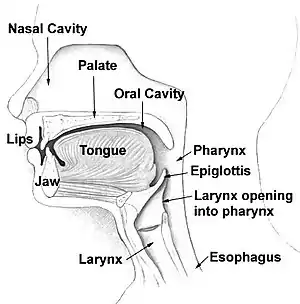

The nasal cavity is a large, air-filled space above and behind the nose in the middle of the face. The nasal septum divides the cavity into two cavities,[1] also known as fossae.[2] Each cavity is the continuation of one of the two nostrils. The nasal cavity is the uppermost part of the respiratory system and provides the nasal passage for inhaled air from the nostrils to the nasopharynx and rest of the respiratory tract.

The paranasal sinuses surround and drain into the nasal cavity.

Structure

The term "nasal cavity" can refer to each of the two cavities of the nose, or to the two sides combined.

The lateral wall of each nasal cavity mainly consists of the maxilla. However, there is a deficiency that is compensated for by the perpendicular plate of the palatine bone, the medial pterygoid plate, the labyrinth of ethmoid and the inferior concha. The paranasal sinuses are connected to the nasal cavity through small orifices called ostia. Most of these ostia communicate with the nose through the lateral nasal wall, via a semi-lunar depression in it known as the semilunar hiatus. The hiatus is bound laterally by a projection known as the uncinate process. This region is called the ostiomeatal complex.[3]

The roof of each nasal cavity is formed in its upper third to one half by the nasal bone and more inferiorly by the junctions of the upper lateral cartilage and nasal septum. Connective tissue and skin cover the bony and cartilaginous components of the nasal dorsum.

The floor of the nasal cavities, which also form the roof of the mouth, is made up by the bones of the hard palate: the horizontal plate of the palatine bone posteriorly and the palatine process of the maxilla anteriorly. The most anterior part of the nasal cavity is the nasal vestibule.[4] The vestibule is enclosed by the nasal cartilages and lined by the same epithelium of the skin (stratified squamous, keratinized). Within the vestibule, this changes into the typical respiratory epithelium that lines the rest of the nasal cavity and respiratory tract. Inside the nostrils of the vestibule are the nasal hair, which filter dust and other matter that are breathed in. The back of the cavity blends, via the choanae, into the nasopharynx.

The nasal cavity is divided in two by the vertical nasal septum. On the side of each nasal cavity are three horizontal outgrowths called nasal conchae (singular "concha") or turbinates. These turbinates disrupt the airflow, directing air toward the olfactory epithelium on the surface of the turbinates and the septum. The vomeronasal organ is located at the back of the septum and has a role in pheromone detection.

The nasal cavity has a nasal valve area that includes an external nasal valve and an internal nasal valve. The external nasal valve is bounded medially by the columella, laterally by the lateral nasal cartilage, and posteriorly by the nasal sill.[5] The internal nasal valve is bounded laterally by the caudal border of the lateral nasal cartilage, medially by the dorsal nasal septum, and inferiorly by the anterior border of the inferior turbinate.[6] The internal nasal valve is the narrowest region of the nasal cavity and is the primary site of nasal resistance in a normal nose.[7]

Segments

The nasal cavity is divided into two segments: the respiratory segment and the olfactory segment.

- The respiratory segment comprises most of each nasal cavity, and is lined with ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium (also called respiratory epithelium). The conchae, or turbinates, are located in this region. The turbinates have a very vascularized lamina propria (erectile tissue) allowing the venous plexuses of their mucosa to engorge with blood, restricting airflow and causing air to be directed to the other side of the nose, which acts in concert by shunting blood out of its turbinates. This cycle occurs approximately every two and a half hours.

- The olfactory segment is lined with a specialized type of pseudostratified columnar epithelium, known as olfactory epithelium, which contains receptors for the sense of the smell. This segment is located in and beneath the mucosa of the roof of each nasal cavity and the medial side of each middle turbinate. Histological sections appear yellowish-brown due to the presence of lipofuscin pigments. Olfactory mucosal cell types include bipolar neurons, supporting (sustentacular) cells, basal cells, and Bowman's glands. The axons of the bipolar neurons form the olfactory nerve (cranial nerve I) which enters the brain through the cribriform plate. Bowman's glands are serous glands in the lamina propria, whose secretions trap and dissolve odoriferous substances.

Blood supply

There is a rich blood supply to the nasal cavity. Blood supply comes from branches of both the internal and external carotid artery, including branches of the facial artery and maxillary artery. The named arteries of the nose are:

- Sphenopalatine artery and greater palatine artery, branches of the maxillary artery.

- Anterior ethmoidal artery and posterior ethmoidal artery, branches of the ophthalmic artery

- Septal branches of the superior labial artery, a branch of the facial artery, which supplies the vestibule of the nasal cavity.[8]

Nerve supply

Innervation of the nasal cavity responsible for the sense of smell is via the olfactory nerve, which sends microscopic fibers from the olfactory bulb through the cribriform plate to reach the top of the nasal cavity.

General sensory innervation is by branches of the trigeminal nerve (V1 & V2):

- Nasociliary nerve (V1)

- Anterior Ethmoidal nerve from the nasociliary nerve (V1)

- Posterior nasal branches of Maxillary nerve (V2)

The nasal cavity is innervated by autonomic fibers. Sympathetic innervation to the blood vessels of the mucosa causes them to constrict, while the control of secretion by the mucous glands is carried on postganglionic parasympathetic nerve fibers originating from the facial nerve.

Function

The two nasal cavities condition the air to be received by the other areas of the respiratory tract. Owing to the large surface area provided by the nasal conchae (also known as turbinates), the air passing through the nasal cavity is warmed or cooled to within 1 degree of body temperature. In addition, the air is humidified, and dust and other particulate matter is removed by nasal hair in the nostrils. The entire mucosa of the nasal cavity is covered by a blanket of mucus, which lies superficial to the microscopic cilia and also filters inspired air. The cilia of the respiratory epithelium move the secreted mucus and particulate matter posteriorly towards the pharynx where it passes into the esophagus and is digested in the stomach. The nasal cavity also houses the sense of smell and contributes greatly to taste sensation through its posterior communication with the mouth via the choanae.

Clinical significance

Diseases of the nasal cavity include viral, bacterial and fungal infections, nasal cavity tumors, both benign and much more often malignant, as well as inflammations of the nasal mucosa. Many problems can affect the nose, including:

- Deviated septum - a shifting of the wall that divides the nasal cavity into halves

- Nasal polyps - soft growths that develop on the lining of the nose or sinuses

- Nosebleeds

- Rhinitis - inflammation of the nose and sinuses sometimes caused by allergies. The main symptom is a runny nose.

- Nasal fractures, also known as a broken nose

- Common cold

- Sinonasal tumors [9]

See also

References

- ↑ Standring S (2016). Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (Forty-first ed.). Elsevier. pp. 556–565. ISBN 978-0-7020-5230-9.

- ↑ "Nasal fossa". TheFreeDictionary.com.

- ↑ Knipe H. "Ostiomeatal complex". Radiology Reference Article. Radiopaedia.org.

- ↑ Beitler JJ, McDonald MW, Wadsworth JT, Hudgins PA (2016). "Sinonasal Cancer". Clinical Radiation Oncology. Elsevier. pp. 673–697.e2. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-24098-7.00036-8. ISBN 978-0-323-24098-7.

The nasal vestibules are the two entry points into the nasal cavity. Each is a triangle-shaped space situated in front of the limen nasi and defined laterally by the lateral crus and alar fibrofatty tissue, medially by the medial crus of the alar cartilage and the nasal septum and the distal end of the cartilaginous septum, and columella.

- ↑ Hamilton, Grant S. (May 2017). "The External Nasal Valve". Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 25 (2): 179–194. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2016.12.010. ISSN 1558-1926. PMID 28340649.

- ↑ Murthy, V. Ashok; Reddy, R. Raghavendra; Pragadeeswaran, K. (August 2013). "Internal Nasal Valve and Its Significance". Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery. 65 (Suppl 2): 400–401. doi:10.1007/s12070-013-0618-x. ISSN 2231-3796. PMC 3738809. PMID 24427685.

- ↑ Fraioli, Rebecca E.; Pearlman, Steven J. (2013-09-01). "A Patient With Nasal Valve Compromise". JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 139 (9): 947–950. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2013.4163. ISSN 2168-6181.

- ↑ Moore KL, Dalley AF (1999). Clinically Oriented Anatomy (Fourth ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-683-06141-3.

- ↑ Schwartz JS, Tajudeen BA, Kennedy DW (2019). "Diseases of the nasal cavity". Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 164: 285–302. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-63855-7.00018-6. ISBN 978-0-444-63855-7. PMC 7151940. PMID 31604553.

External links

- lesson9 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University)

- Gross anatomy dissection of the nasal cavity, video and