| Narragansett Bay | |

|---|---|

| |

Narragansett Bay | |

| Location | Rhode Island, Massachusetts, United States |

| Coordinates | 41°36′N 71°21′W / 41.600°N 71.350°W |

| Type | Bay |

| Surface area | 147 square miles (380 km2) |

Narragansett Bay is a bay and estuary on the north side of Rhode Island Sound covering 147 square miles (380 km2), 120.5 square miles (312 km2) of which is in Rhode Island.[1] The bay forms New England's largest estuary, which functions as an expansive natural harbor and includes a small archipelago.[2] Small parts of the bay extend into Massachusetts.

There are more than 30 islands in the bay; the three largest ones are Aquidneck Island, Conanicut Island, and Prudence Island.[3] Bodies of water that are part of Narragansett Bay include the Sakonnet River, Mount Hope Bay, and the southern, tidal part of the Taunton River. The bay opens on Rhode Island Sound and the Atlantic Ocean; Block Island lies less than 20 miles (32 km) southwest of its opening.

Etymology

"Narragansett" is derived from the southern New England Algonquian word Naiaganset meaning "(people) of the small point of land".[4]

Geography

The watershed of Narragansett Bay has seven river sub-drainage basins, including the Taunton, Pawtuxet, and Blackstone Rivers, and they provide freshwater input at approximately 2.1 million U.S. gallons (7.9×106 L) per day.[5] River water inflow has a seasonal variability, with the highest flow in the spring and the minimum flow in early fall.[6]

The bay is a ria estuary (a drowned river valley) which is composed of the Sakonnet River valley, the East Passage river valley, and the West Passage river valley. The bathymetry varies greatly among the three passages, with the average depths of the East, West, and Sakonnet River passages being 121 feet (37 m), 33 feet (10 m), and 25 feet (7.6 m) respectively.[7] Narragansett Bay is a ria that consists of a series of flooded river valleys formed of dropped crustal blocks in a horst and graben system[8] that is slowly subsiding between a shifting fault system.[9]

Providence is Rhode Island's capital and largest city and sits at the northernmost arm of the bay. Many of Providence's suburbs are also on the bay, including East Providence, Warwick and Cranston. Newport is located at the south end of Aquidneck Island on the ocean, and is the home of the United States Naval War College, the Naval Undersea Warfare Center, and a major United States Navy training center. The city of Fall River, Massachusetts is located at the confluence of the Taunton River and Mount Hope Bay, which form the northeasternmost part of Narragansett Bay. The southwest side of the bay includes the seaside tourist towns of Narragansett and Wickford. Quonset Point, south of Warwick, gives its name to the Quonset hut.

Oceanography

Tidal patterns

Tides in the watershed are measured at Providence, Fall River, Quonset Point, Conimicut Light, Prudence Island, and Newport. In shallow water, sound waves are used to measure water height by precisely measuring their travel time. In deeper water, tides are measured with pressure-sensing tide gauges that are placed on the ocean floor to measure water height.

The bay's tides are semi-diurnal, meaning that the region experiences two high and low tides daily. The tides range in height from 3.6 feet (1.1 m) at the bay's mouth and 4.6 feet (1.4 m) at its head. Water depth varies about 4 feet (1.2 m) between high and low tide. The lunar, semi-diurnal M2 tide occurs at a period of 12.42 hours, with two tides occurring in the watershed every 24 hours and 50 minutes. The watershed's neap and spring tides occur every 14.8 days. In Narragansett bay, the tides show a distinct double-peak flood during high tide and single peak ebb during low tide.[10]

Water circulation patterns

The movement of water within a system is its circulation. Estuaries are given a classification depending on the pattern of their circulations. The circulation classification can be well-mixed, partially mixed, salt wedge, or Fjord-type. For Narragansett, the circulation is mostly well-mixed; however, the Providence River does show some vertical stratification.

Narragansett Bay circulation is made up of forces provided by the winds, tides, and changes in water density within the watershed. Its circulation is the result of the flow of fresh water at the head interacting with salt water at the point where the bay meets the open ocean. Residence time of water due to the circulation of Narragansett Bay is 10–40 days, with an average of 26 days.[7] Tidal mixing is the dominant driver of circulation patterns in the bay, where currents can reach up to 2.5 feet per second. Non-tidal currents such as the flow of low salinity water at the surface out of the bay and high salinity deep water into the bay contribute to a current of about 0.33 feet per second.[7]

Winds also drive circulation patterns in the bay. In the winter, winds come from the northwest, helping move water towards the bay's mouth; in the summer, they are out of the southwest and move water towards the head of the bay. Wind-driven waves of over 4.25 feet (1.30 m) also help mix surface waters.

Density-driven forces are the third factor affecting circulation. Fresh water inflow comes from natural sources such as atmospheric precipitation and inflow from the many rivers that feed into the watershed, and human-made sources such as water treatment plants. Fresh and saltwater mixing results in a salinity range in the bay of 24 parts per thousand (ppt) in the upper Providence River area to 32 ppt at the mouth of the bay.

The bay's currents and circulation patterns greatly influence the sediment deposits within the region. The majority of the sediments within the bay are fine-grained material such as detritus, clay-silt, and sand-silt-clay. Scientists have been able to identify 11 types of sediment that range from coarse gravels to fine silts.[7] the bay's currents deposit fine materials through the harbors of the lower and middle sections of the bay, and the coarse, heavy materials are deposited in the lower areas of the bay where the water velocities are higher.

Early history

The first visit by Europeans to the bay was probably in the early 16th century. At the time, the area surrounding the bay was inhabited by two different Indian tribes: the Narragansetts occupied the west side of the bay, and the Wampanoags lived on the east side, occupying the land east to Cape Cod.

It is accepted by most historians that first contact by Europeans was made by Giovanni da Verrazzano, an Italian explorer who entered the bay in his ship La Dauphine in 1524 after visiting New York Bay. Verrazzano called the bay Refugio, the "Refuge". It has several entrances, however, and historians can only speculate as to the exact route of his voyage and the location where he laid anchor, along with a corresponding uncertainty over which tribe made contact with him.[11][12] Verrazzano reported that he found clearings and open forests suitable for travel "even by a large army".[13] Dutch navigator Adriaen Block explored and mapped the bay in 1614, and nearby Block Island is named in his honor.

The first permanent Colonial settlement was established in 1636 by Roger Williams, a former member of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. He was friends with Narragansett sachem Canonicus, who provided him with land on which to build Providence Plantations. Around the same time, the Dutch established a trading post approximately 12 miles (20 km) to the southwest which was under the authority of New Amsterdam in New York Bay. In 1643, Williams traveled to England and was granted a charter for the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.

The Gaspee Affair was an important naval event which moved the Thirteen Colonies toward the American Revolution. It occurred in Narragansett Bay in 1772 and involved the capture and burning of the British customs schooner Gaspee. The American victory contributed to the eventual start of the war at the Battles of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts three years later. The event is celebrated in Pawtuxet Village as the Gaspee Days Celebration[14] in June which includes burning the ship in effigy.

Roger Williams and other early colonists named the islands[15] Prudence, Patience, Hope, Despair, and Hog. To remember the names, colonial school children often recited the poem: "Patience, Prudence, Hope, and Despair. And the little Hog over there."[16]

Water properties and phytoplankton distribution

Narragansett Bay is divided by Conanicut Island into east and west passages. Its depth averages approximately 9.0 meters throughout the bay, but it is shallower in the west passage and deeper in the east.[17] Narragansett Bay receives freshwater input from several sources, including rivers (approximately 80%), direct precipitation (13%), wastewater treatment facilities (9%), and unknown amounts from ground-water and combined sewer overflows (CSOs).[17] The freshwater input varies greatly from season to season as it is highest in winter and lowest in summer, while CSOs increase dramatically following heavy rain. Water from these freshwater inputs mixes with sea water to form a salinity gradient ranging from 24 ppt at the mouth of the Providence River to 32 ppt at the mouth of the bay.[17] Water temperatures range between -0.5 °C and 24 °C over the year. Salinity and temperature patterns measured throughout the bay indicate a range of mixed to stratified conditions [18] and the amount of time it takes for the total volume of fresh water in the bay to be equaled by the fresh water input (flushing time) varies from 40 days to 10 days, depending on freshwater input.[19]

Dissolved oxygen levels in Narragansett Bay are seasonal with lower levels in the summer and higher levels in the winter. This is due to warmer temperatures and higher biological demand for oxygen in the summer and the opposite in the winter. Narragansett Bay is also subject to periodic summer hypoxic events in the Northern half of the bay, nearing anoxic conditions in some parts.[20]

Phytoplankton forms the base of the food chain for many of the bay's marine animals. General trends in phytoplankton biomass across the bay are characterized by highest levels in the Providence River and lowest levels in Rhode Island Sound, correlating with the North to South nutrient concentration gradient in the bay (24). Near the Providence River, biomass levels are highest in the summer and lowest in the winter. In the east and west passages there are peaks in the spring and fall.[21]

Annual blooms have shrunk over the last decade (2006 onward) as the amount of nitrogen (an important nutrient) supply to the bay has decreased by more than 50% due to wastewater treatment facilities switching to a new treatment that involves removal of nitrogen [22]

Narragansett Bay is the site of one of the world's longest-running plankton surveys, extending from 1957 through the present. Researchers at the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography collect samples weekly and the dataset contains 246 different species.[23]

Rivers

- Blackstone River, Woonsocket, Cumberland, Lincoln, Central Falls, and Pawtucket, RI

- Seekonk River, Pawtucket, East Providence, and Providence, RI

- Ten Mile River, Pawtucket and East Providence, RI

- Moshassuck River, Providence, RI

- Woonasquatucket River, Providence, RI

- Providence River, Providence, Cranston, Warwick, East Providence, and Barrington, RI

- Pawtuxet River, Cranston and Warwick, RI

- Potowomut River, also called Greene River, Warwick, and North Kingstown, RI

- Quequechan River, Fall River, MA

- Barrington River, Barrington, RI

- Palmer River, Barrington and Warren, RI

- Warren River, Warren and Barrington, RI

- Taunton River, Fall River, MA

- Sakonnet River, Tiverton, Little Compton, Portsmouth, and Middletown, RI

- Kickamuit River, Warren and Bristol, RI

Notes

- ↑ 1998 Journal-Bulletin Rhode Island Almanac, 112th Annual Edition, p. 36.

- ↑ Keller, Aimee A.; Klein-MacPhee, Grace; Burns, Jeanne St. Onge (January 1, 1999). "Abundance and Distribution of Ichthyoplankton in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, 1989–1990". Estuaries. 22 (1): 149–163. doi:10.2307/1352935. JSTOR 1352935. S2CID 84501320.

- ↑ "The Islands – City of Providence Website". Providenceri.com. Archived from the original on April 10, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2010.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "Narragansett". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on January 20, 2010. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Facts and Figures About Narragansett Bay - Save The Bay". www.savebay.org. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ↑ Spaulding, Malcolm L.; Swanson, Craig (January 1, 2008). "Circulation and Transport Dynamics in Narragansett Bay". In Desbonnet, Alan; Costa-Pierce, Barry A. (eds.). Science for Ecosystem-based Management. Springer Series on Environmental Management. Springer New York. pp. 233–279. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-35299-2_8. ISBN 9780387352992 – via link.springer.com.

- 1 2 3 4 "Ecological Geography of Narragansett Bay" (PDF). nbnerr.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 6, 2012. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ↑ Robert L. McMaster, Jelle de Boer, and Barclay P. Collins, "Tectonic development of southern Narragansett Bay and offshore Rhode Island", Geology 8.10 (October 1980:496–500) (On-line abstract).

- ↑ The faults produce earthquakes upon occasion, according to the USGS: "Rhode Island Earthquake History" Archived 2009-08-25 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Physical Properties: Circulation: Tides, from Discovery of Estuarine Environments (DOEE)". Archived from the original on January 29, 2014.

- ↑ "Refugio". Archived from the original on January 23, 2003. Retrieved January 21, 2004.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 13, 2003. Retrieved January 21, 2004.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ W. Conon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists and the Ecology of New England (New York) 1983.

- ↑ DRC. "Gaspee Days Committee". Gaspee.com. Archived from the original on February 3, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2010.

- ↑ "Roger Williams Biography".

- ↑ "Prudence Island Lighthouse History". Lighthouse.cc. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Narragansett Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve. 2009. An Ecological Profile of the Narragansett Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve.K.B. Raposa and M.L. Schwartz (eds.), Rhode Island Sea Grant, Narragansett, R.I. 176pp.

- ↑ Oviatt, C., Keller, A., & Reed, L. (2002). Annual primary production in Narragansett Bay with no bay-wide winter-spring phytoplankton bloom. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 54(6), 1013–1026. https://doi.org/10.1006/ecss.2001.0872

- ↑ Pilson, M. E. Q. (1985). On the residence time of water in Narragansett Bay. Estuaries, 8(1), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/1352116

- ↑ Melrose, D. C., Oviatt, C. A., & Berman, M. S. (2007). Hypoxic events in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, during the summer of 2001. Estuaries and Coasts, 30(1), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02782966

- ↑ Oviatt, C., Keller, A., & Reed, L. (2002). Annual primary production in Narragansett Bay with no bay-wide winter-spring phytoplankton bloom. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 54(6), 1013–1026. https://doi.org/10.1006/ecss.2001.0872.

- ↑ Oczkowski, A., Schmidt, C., Santos, E., Miller, K., Hanson, A., Cobb, D., … Rd, T. (2018). How the distribution of anthropogenic nitrogen has changed in Narragansett Bay (RI, USA) following major reductions in nutrient loads. Estuaries Coast, 41(8), 2260–2276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-018-0435-2.

- ↑ The Narragansett Bay Long-Term Plankton Time Series, https://web.uri.edu/gso/research/plankton/.

External links

- Narragansett Bay Research Reserve on Prudence Island

- Narragansett Bay Shipping

- Narragansett Bay: A Friend's Perspective

- Narragansett Bay.Org

- Save the bay

- Narragansett Bay Estuary Program

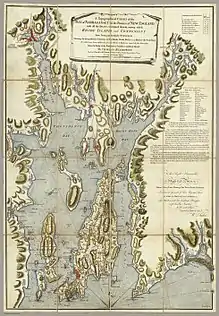

- 1777 Chart/Map of Narragansett Bay by Charles Blaskowitz and William Faden at DavidRumsey.com

- Guide to the Rhode Island Leased Oyster Bed Grounds Indenture records from the Rhode Island State Archives

- 1983 Narragansett Bay Commission Annual Report from the Rhode Island State Archives