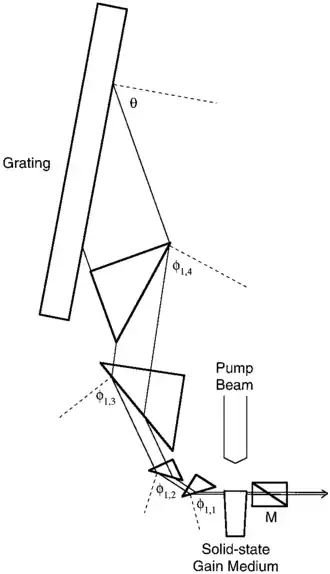

Multiple-prism grating laser oscillators,[1] or MPG laser oscillators, use multiple-prism beam expansion to illuminate a diffraction grating mounted either in Littrow configuration or grazing-incidence configuration. Originally, these narrow-linewidth tunable dispersive oscillators were introduced as multiple-prism Littrow (MPL) grating oscillators,[2] or hybrid multiple-prism near-grazing-incidence (HMPGI) grating cavities,[3][4] in organic dye lasers. However, these designs were quickly adopted for other types of lasers such as gas lasers,[5][6] diode lasers,[7][8] and more recently fiber lasers.[9]

Excitation

Multiple-prism grating laser oscillators can be excited either electrically, as in the case of gas lasers and semiconductor lasers,[11] or optically, as in the case of crystalline lasers and organic dye lasers.[1] In the case of optical excitation it is often necessary to match the polarization of the excitation laser to the polarization preference of the multiple-prism grating oscillator.[1] This can be done using a polarization rotator thus improving the laser conversion efficiency.[11]

Linewidth performance

The multiple-prism dispersion theory is applied to design these beam expanders either in additive configuration, thus adding or subtracting their dispersion to the dispersion of the grating, or in compensating configuration (yielding zero dispersion at a design wavelength) thus allowing the diffraction grating to control the tuning characteristics of the laser cavity.[11] Under those conditions, that is, zero dispersion from the multiple-prism beam expander, the single-pass laser linewidth is given by[1][11]

where is the beam divergence and M is the beam magnification provided by the beam expander that multiplies the angular dispersion provided by the diffraction grating. In the case of multiple-prism beam expanders this factor can be as high as 100–200.[1][11]

When the dispersion of the multiple-prism expander is not equal to zero, then the single-pass linewidth is given by[1][11]

where the first differential refers to the angular dispersion from the grating and the second differential refers to the overall dispersion from the multiple-prism beam expander.[1][11]

Optimized solid-state multiple-prism grating laser oscillators have been shown, by Duarte, to generate pulsed single-longitudinal-mode emission limited only by Heisenberg's uncertainty principle.[12] The laser linewidth in these experiments is reported as ≈ 350 MHz (or ≈ 0.0004 nm at 590 nm) in pulses ~ 3 ns wide, at power levels in the kW regime.[12]

Applications

Applications of these tunable narrow-linewidth lasers include:

- Coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy and combustion diagnostics[13]

- LIDAR[14]

- Laser spectroscopy[15][16]

- Atomic vapor laser isotope separation[17][18]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 F. J. Duarte, Narrow-linewidth pulsed dye laser oscillators, in Dye Laser Principles (Academic, New York, 1990) Chapter 4.

- ↑ F. J. Duarte and J. A. Piper, A double-prism beam expander for pulsed dye lasers, Opt. Commun. 35, 100-104 (1980).

- ↑ F. J. Duarte and J. A. Piper, A prism preexpanded grazing incidence pulsed dye laser, Appl. Opt. 20, 2113-2116 (1981).

- ↑ F. J. Duarte and J. A. Piper, Narrow linewidth high prf copper laser-pumped dye-laser oscillators, Appl. Opt. 23, 1391-1394 (1984).

- ↑ F. J. Duarte, Multiple-prism Littrow and grazing incidence pulsed CO2 lasers, Appl. Opt. 24, 1244-1245 (1985).

- ↑ R. C. Sze and D. G. Harris, Tunable excimer lasers, in Tunable Lasers Handbook, F. J. Duarte (Ed.) (Academic, New York, 1995) Chapter 3.

- ↑ P. Zorabedian, Characteristics of a grating-external-cavity semiconductor laser containing intracavity prism beam expanders, J. Lightwave Tech. 10, 330–335 (1992).

- ↑ P. Zorabedian, Tunable external cavity semiconductor lasers, in Tunable Lasers Handbook, F. J. Duarte (Ed.) (Academic, New York, 1995) Chapter 8.

- ↑ T. M. Shay and F. J. Duarte, in Tunable Laser Applications, 2nd Ed., F. J. Duarte (Ed.) (CRC, New York, 2009) Chapter 9.

- ↑ F. J. Duarte, T. S. Taylor, A. Costela, I. Garcia-Moreno, and R. Sastre, Long-pulse narrow-linewidth disperse solid-state dye laser oscillator, Appl. Opt. 37, 3987–3989 (1998).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 F. J. Duarte, Tunable Laser Optics, 2nd Ed. (CRC, New York, 2015).

- 1 2 F. J. Duarte, Multiple-prism grating solid-state dye laser oscillator: optimized architecture, Appl. Opt. 38, 6347-6349 (1999).

- ↑ R. J. Hall and A. C. Eckbreth, Coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy: applications to combustion diagnostics, in Laser Applications (Academic, New York, 1984) pp. 213-309.

- ↑ W. B. Grant, Lidar for atmospheric and hydrospheric studies, in Tunable Laser Applications, 1st Ed. (Marcel-Dekker, New York, 1995) Chapter 7.

- ↑ W. Demtröder, Laserspektroscopie: Grundlagen und Techniken, 5th Ed. (Springer, Berlin, 2007).

- ↑ W. Demtröder, Laser Spectroscopy: Basic Principles, 4th Ed. (Springer, Berlin, 2008).

- ↑ S. Singh, K. Dasgupta, S. Kumar, K. G. Manohar, L. G. Nair, U. K. Chatterjee, High-power high-repetition-rate capper-vapor-pumped dye laser, Opt. Eng. 33, 1894-1904 (1994).

- ↑ A. Sugiyama, T. Nakayama, M. Kato, Y. Maruyama, T. Arisawa, Characteristics of a pressure-tuned single-mode dye laser oscillator pumped by a copper vapor oscillator, Opt. Eng. 35, 1093-1097 (1996).